Episode 88: Improving Voucher Outcomes with Dionissi Aliprantis

Episode Summary: Helping people move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods requires knowing which neighborhoods are actually better. Are we any good at it? Dionissi Aliprantis shares his research on measuring neighborhood opportunity and the rent assistance program features that could meaningfully reduce racial segregation.

Abstract: Housing Mobility Programs (HMPs) support residential mobility to reduce economic segregation. One design feature of HMPs requires identifying areas to which moving will most improve outcomes. We show that ranking neighborhoods’ effects using current residents’ outcomes has strengths over using previous residents’ outcomes due to statistical uncertainty, bias from sorting over time, and lack of support. We simulate how the choice of neighborhood ranking and others affect an originally-intended outcome of HMPs: reducing racial segregation. HMP success on this dimension depends on the ability to port vouchers across jurisdictions, access to cars, and the range of neighborhoods targeted.

Show notes:

- Aliprantis, D., Martin, H., & Tauber, K. (2024). What determines the success of housing mobility programs? Journal of Housing Economics, 65, 102009.

- 99% Invisible episode on chambre le bonne (maid’s rooms) in Paris.

- Episode 87 of UCLA Housing Voice, on housing voucher lease-up rates with Sarah Strochak.

- Episode 17 of UCLA Housing Voice, on using fair market rents to improve housing vouchers with Rob Collinson.

- Episode 58 of UCLA Housing Voice, on the health impacts of Baltimore’s housing mobility program with Craig Pollack.

- The book, Waiting for Gautreaux: A Story of Segregation, Housing, and the Black Ghetto, by Alexander Polikoff.

- Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hendren, N., Jones, M. R., & Porter, S. R. (2018). The Opportunity Atlas: Mapping the childhood roots of social mobility (No. w25147). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Bergman, P., Chetty, R., DeLuca, S., Hendren, N., Katz, L. F., & Palmer, C. (2024). Creating Moves to Opportunity: Experimental evidence on barriers to neighborhood choice. American Economic Review, 114(5), 1281-1337.

- “Housing mobility programs (HMPs) are a model that is receiving renewed attention in the design of public housing policy. The first HMP, Gautreaux, began in 1976 and supported Black households in Chicago moving from public housing to suburban neighborhoods with a low share of Black residents (Polikoff, 2006). Subsequent HMPs have encouraged moves to higher-income neighborhoods with varying degrees of focus on racial segregation.”

- “The success of HMPs in empowering moves to opportunity has varied widely. Fig. 1 shows the 2019 results of two prominent HMPs, Creating Moves to Opportunity (CMTO) and the Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership (BRHP). While both of these HMPs are regarded as being very successful, they have clearly resulted in different levels of success in moving their participants to lower poverty neighborhoods. CMTO moved the typical participant from the 23rd percentile to the 41st percentile of neighborhood poverty rates for non-Hispanic whites, but those who moved in the BRHP typically increased from the 5th to the 77th percentile.”

- “What determines the success of such HMPs? This paper breaks the question into two parts, the first of which is an econometric question: How can we identify the areas to which moving will most improve the outcomes of participants? The second question is about implementation: How can policy best support moves to those areas identified as offering the greatest opportunity for participants?”

- “Step 1 of canonical approaches to understanding neighborhood effects is measuring the neighborhood characteristics that theory suggests affect residents’ outcomes. Two examples are neighborhood quality (Aliprantis, 2017) and the Child Opportunity Index (COI, Noelke et al., 2020) … After ordering neighborhoods, Step 2 of canonical approaches is to use exogenous variation and/or a model of sorting to identify the effects of those characteristics on outcomes (recent examples include Altonji and Mansfield (2018) and Aliprantis and Richter (2020)).”

- “A new approach to identifying neighborhood effects is made possible by an administrative data set, the Opportunity Atlas (OA, Chetty et al., 2020a). The OA combines Steps 1 and 2 and orders neighborhoods by estimating the mean adult outcomes of a tract’s previous residents rather than the outcomes of its current residents, both overall and conditional on race or parental income. The OA has been used both to rank and to predict neighborhoods’ effects while eschewing the canonical approach’s search for exogenous variation or modeling.”

- “The first contribution of this paper is to show that using the outcomes of contemporaneous residents has several strengths over using the outcomes of previous residents for the ranking of neighborhood effects … The second contribution of this paper is to quantify the relative importance of design features in reducing racial inequality by helping program participants move to areas designated as high opportunity.”

- “Several factors aiding successful moves have already been identified (Scott et al., 2013): Landlord outreach, pre-search counseling, housing search assistance, post-move support, and voucher values tied to rents in small areas.2 Several additional factors, however, are not as well understood. For example, how important is it that vouchers needed to be ported across Public Housing Authority (PHA) jurisdictions in some previous HMPs but not in others? We know that there is a low supply of units in high-rent areas and that landlords increasingly avoid voucher tenants as rents increase (Phillips, 2017). How binding is this constraint, and might we be able to relax supply constraints by targeting lower-ranked tracts? Likewise, we know that higher rent areas have less access to public transportation. How important is this constraint, and might we be able to relax it by assisting HMP participants in accessing cars or ride shares?”

- “There are many ways to rank neighborhoods, and here we consider three rankings of neighborhood-level outcomes, where we define neighborhoods as Census tracts.3 Each ranking of neighborhoods is in terms of the national distribution of individuals, although we note the cases when we use metro-level rankings … The first ranking, “neighborhood quality”, is an index used in Aliprantis and Richter (2020), which is the ranking of the first principal component of a tract’s national rankings on six socioeconomic characteristics. The six characteristics used to calculate neighborhood quality are the poverty rate, the share of adults 25+ with a high school diploma, the share of adults 25+ with a BA, the Employment to Population Ration for adults 16+, the labor force participation rate for adults 16+, and the share of families with children under 18 with only a mother or father present.”

- “The second ranking is the Childhood Opportunity Index 2.0 (COI). Developed at Brandeis University (Noelke et al., 2020), the COI aggregates information from 29 items, many of which come from data sources beyond the Census, like the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It is useful to see the COI as a generalization of neighborhood quality that incorporates information from additional variables that we think should affect a neighborhood’s residents.”

- “The third ranking comes from the Opportunity Atlas (OA), which estimates the average outcomes for individuals born between 1978 and 1983 who spent time residing in a given neighborhood (Chetty et al., 2020a). This birth cohort corresponds to children aged 6–11 in the 1990 Census. Unless otherwise stated, our analysis focuses on the OA ranking of neighborhoods based on the estimated average family income between ages 31–37 for children who had parents at the 25th percentile of income.”

- “Many HMPs encourage participants to move to the top third of local tracts according to some ranking of neighborhoods. Different rankings often disagree about where such a program should encourage participants to move. Fig. 2 shows the disagreement between the top third of tracts in Baltimore as identified by each ranking we consider in our analysis. While these rankings agree about the top-third status of many tracts, there are many tracts over which they disagree. The disagreement between OA and quality is considerably higher than is the disagreement between COI and quality. OA and quality disagree on the top-third ranking of 140 tracts, while COI and quality only generate this disagreement for 71 tracts, out of 671 tracts total. Which ranking should a PHA use to define the opportunity areas to which they encourage moves?”

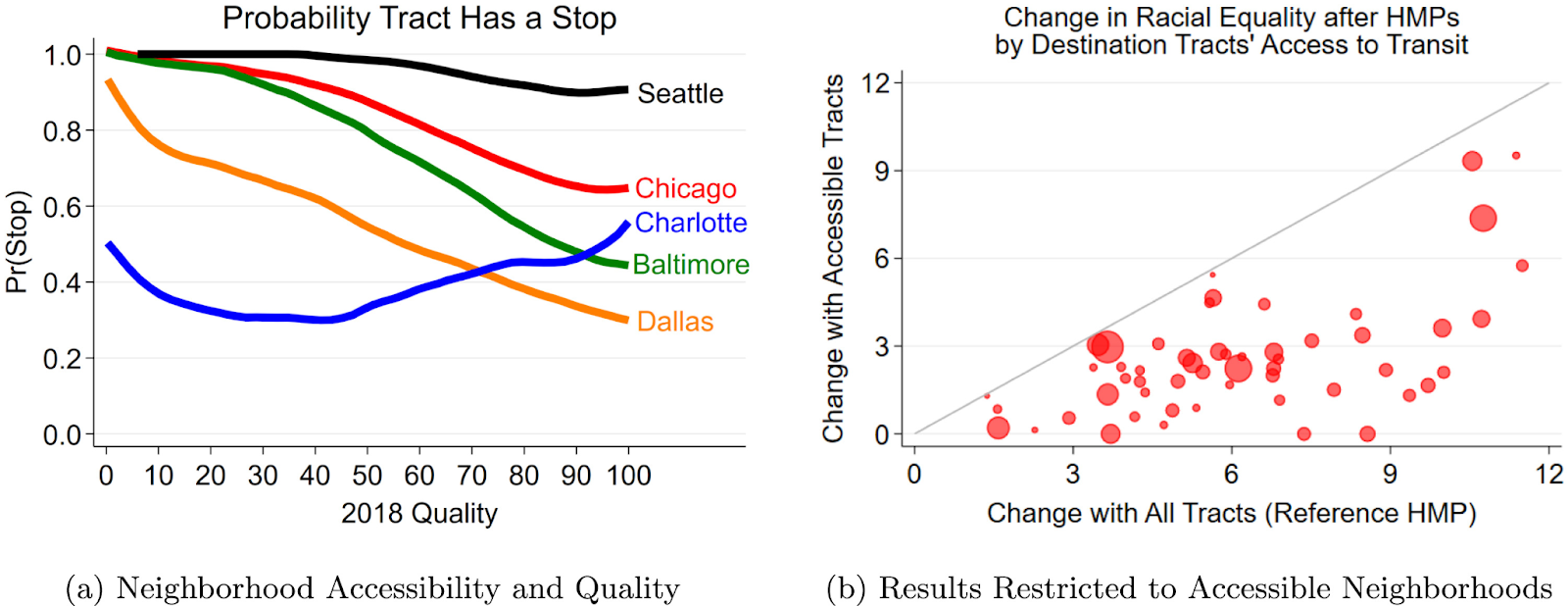

- “How much does this statistical disagreement matter for the design of HMPs? Fig. 3(b) shows the changes in racial equality that would result for the baseline HMP designed around quality, where both the measure of racial inequality and the baseline HMP are discussed in Section 3 … The fact that the green dots representing the OA tend to fall below the 45 degree line indicates that an HMP targeting quality will improve OA less in a quantitatively important way; the improvement in OA would on average be 75 percent of the improvement in quality.”

- “Neighborhood sorting leads to both statistical and conceptual uncertainty in the case of measuring income-specific outcomes. Here we focus on statistical uncertainty. The 1990 Decennial Census directly measures the number of children aged 6–11 in each tract, as well as the number of Black or white boys aged 6–11. Fig. 4 shows that the disagreement between OA and quality is the largest in tracts with very few children.”

- “Opportunity bargains are neighborhoods with strong, positive effects on residents that also have low rents. How should we think about using alternative rankings to identify such neighborhoods? Chetty et al. (2020a) argue that the OA is the best measure to target opportunity bargains when implementing HMPs. Below we find evidence that suggests caution when using the OA to target opportunity bargains: The bias creating low-rent, highly-ranked tracts in the OA is likely in the ranking, not the rent … Fig. 6 shows that the low-rent opportunity bargains identified by the OA are likely to have dropped considerably in quality between 1990 and 2018.7 Recall that Fig. 5 just showed that the low-rent opportunity bargains identified by the OA are likely to have a low ranking according to 2018 quality. When we look at such tracts, where the 2018 quality ranking minus the OA ranking is very negative, say –30 or less, we see in Fig. 6 that these tracts also experienced large declines in quality between 1990 and 2018. Thus, low rents in the “opportunity bargain” tracts whose residents’ outcomes have dropped considerably since the time they were occupied by OA residents likely convey information about the effects of living in such neighborhoods.”

- “When looking at the local ranking of tracts by the OA and neighborhood quality, large disagreements become rare when we plot rankings that do not include tracts with large changes in quality between 1990 and 2018 or small sample sizes. Fig. 7 shows the implications of sorting over time in Chicago for interpreting disagreements between the outcomes of a tract’s current and previous residents.”

- “Targeting outcomes specific to demographic groups could be especially important in the case of race, where the experience of being “Black in white space” could generate different experiences for Black and white individuals occupying the same physical space (Anderson, 2020, Harriot, 2019), a mechanism that has been noted by HMP participants (Lott, 2021) and that could be perpetuating residential segregation at all levels of income and wealth (Aliprantis et al., 2022a). Unfortunately, race-specific outcome estimates are simply not available for the most relevant tracts when designing an HMP. Residential sorting by race is so strong in the US that we have not observed enough Black children growing up in most high-opportunity neighborhoods to estimate race-specific outcomes. Consider Black boys: In the 1990 Census, the median tract in the top half of neighborhood quality had 2 Black boys in the OA sample age range (6–11) … At the lowest levels of quality, most tracts have 50 Black boys or more with which to estimate outcomes. But once quality gets out of the bottom decile, the number of Black boys is already too low to reliably estimate outcomes in many neighborhoods.”

- “The strength of neighborhood sorting by race has implications for how we interpret data-based estimates of the effects of residential segregation (Chetty et al., 2020b, Chyn et al., 2022). We interpret the documented patterns of sorting by race as evidence that using administrative data to study neighborhood effects faces the problem of “bias in, bias out” common to the use of administrative data sets in other settings (Mayson, 2019).9 The implication is that making predictions about outcomes in an unbiased society requires that one invoke theory, as such predictions are outside the support of the data.”

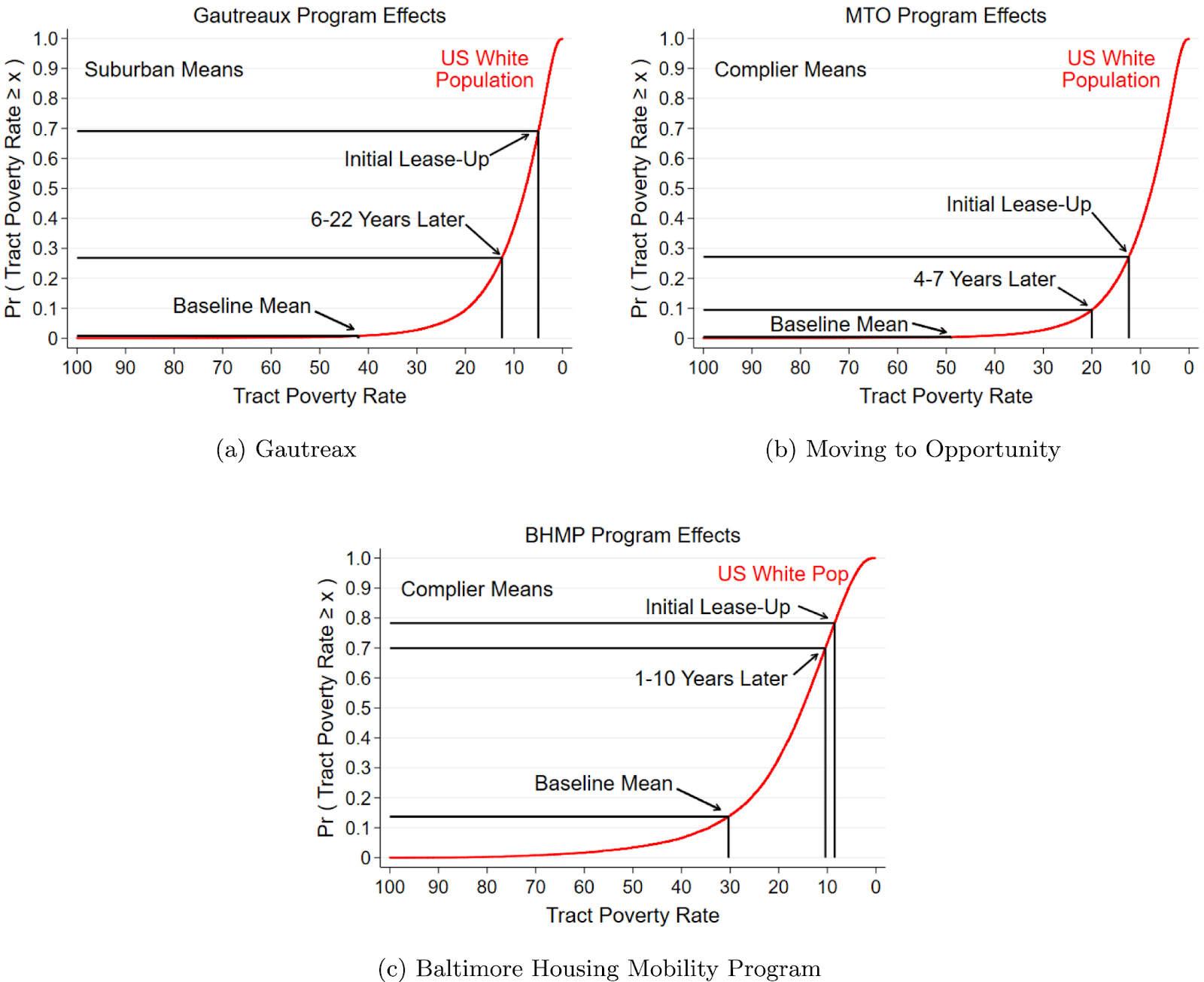

- “The four most-studied HMPs are the Gautreaux HMP (Gautreaux), the Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing (MTO) experiment, the Baltimore HMP (BHMP), and the Creating Moves to Opportunity (CMTO) experiment. Fig. 9 shows how residential outcomes for movers vary across different existing HMPs. Changes in neighborhood poverty rates between baseline and initial lease-up locations were largest in Gautreaux and the BHMP, both of which are regional programs. The gap between initial placement and subsequent locations is the smallest in the BHMP. The long-term success of BHMP participants’ residential outcomes is likely a function of the BHMP’s focus on landlord outreach, tenant counseling, search assistance, and post-move support. These features serve to overcome resistance to subsidized tenants among landlords and increase the effectiveness of search among those tenants, thereby increasing the reachable housing supply.”

Figure 9. Residential outcomes of movers in housing mobility programs.

- “Gautreax and the BHMP have been implemented as regional partnerships, encouraging residents to move beyond a single PHA’s jurisdiction and throughout their respective metropolitan areas. While MTO technically encouraged participants to move across jurisdictions, the program’s Section 8 certificates and vouchers were allocated to the central city PHAs at each site (Feins et al., 1996, p 1–4), and it is unclear how much the obstacles to portability across PHA jurisdictions constrained participants’ choices (Feins et al., 1996, pp 13–4 to 13–9).10 And while CMTO was implemented by two PHAs, the Seattle and King County PHAs, it does not appear that moves across these PHAs’ jurisdictions were encouraged (Bergman et al., 2020b).”

- “Participants in Gautreaux [low-income African Americans in Chicago public housing] were eligible to move to neighborhoods defined in terms of racial composition; eligible tracts were those with no more than 30 percent Black residents (Rosenbaum, 1995). In the BHMP neighborhood eligibility has changed over time. From 2002 until 2015, eligible neighborhoods were those with no more than 30 percent Black residents, no more than 10 percent poverty, and no more than 5 percent of residents receiving housing assistance. From 2015 until today, the BHMP has been administered by the Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership (BRHP), which uses a combination of 21 variables to determine tract eligibility. The eligible neighborhoods in MTO were defined in terms of poverty rates; eligible tracts were those with less than 10 percent poverty. In CMTO, eligible tracts were determined by combining the Opportunity Atlas data with several additional variables in an estimation procedure that shrinks the OA ranking toward contemporaneous variables like 2010 poverty rates and 4th grade test scores (Bergman et al., 2020b, Appendix A).”

- “Tenant counseling pre- and post-move have been a part of each HMP; what has varied considerably across HMPs has been the precise form of counseling provided, financial support to tenants, and outreach to landlords. For example, the BHMP makes its workshops mandatory for program participants. The BHMP and CMTO provide financial assistance toward moving costs, while Gautreaux and MTO did not. And while the BHMP actively recruits landlords in opportunity areas, contacts landlords on behalf of searching clients, and provides mediation between tenants and landlords, these services varied across sites in MTO.”

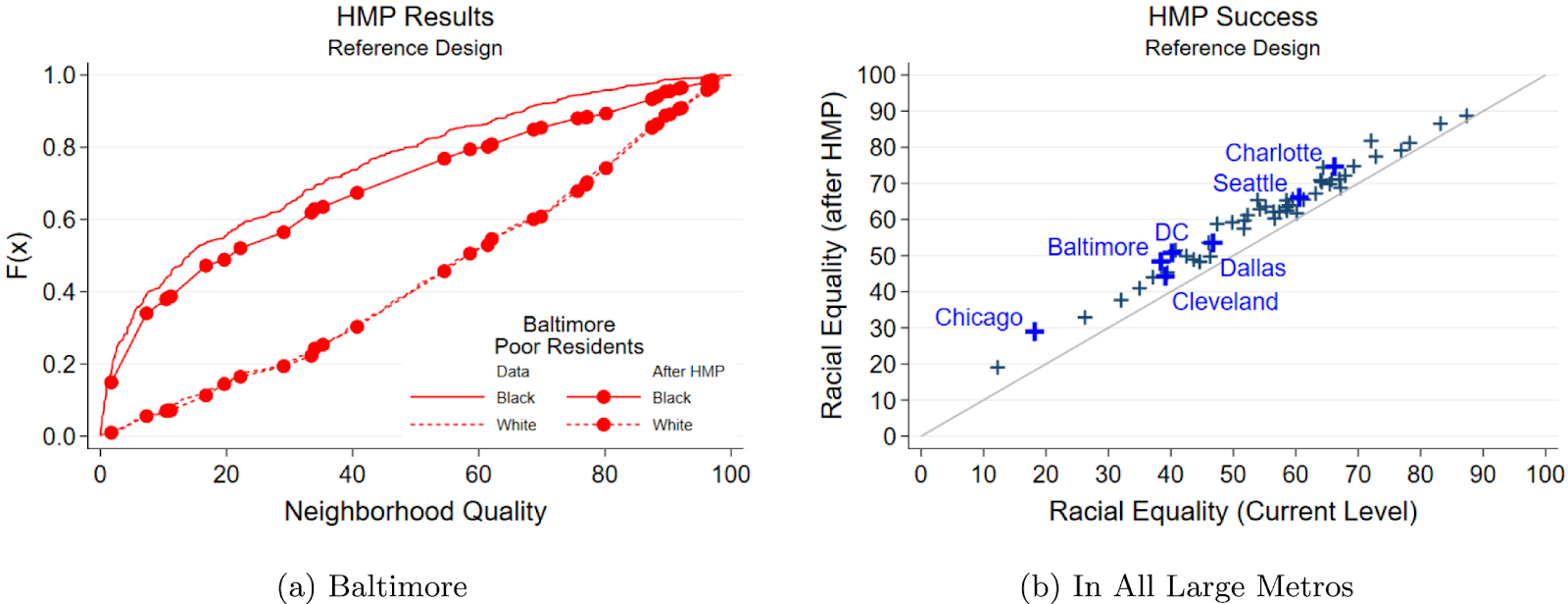

- “Without minimizing the disparities faced by other groups, we focus this analysis on the residential segregation of Blacks and whites. Black neighborhoods have struggled to gain upward mobility in a way ethnic enclaves have not because of specific exclusionary policies, coupled with durable systemic racism and violence that have left many Black communities disinvested of the institutions that support upward mobility (Polikoff, 2006, Rothstein, 2017, Baradaran, 2017). While HMPs are not the only approach to addressing racial segregation, they are a means of addressing the areas of concentrated economic disadvantage that are still with us today. Fig. 10(a) shows the remarkable clustering of poor Black residents in Baltimore in the lowest quality neighborhoods. A third of Baltimore’s poor Black residents live in tracts below the 5th percentile of the national distribution of quality.”

- “Simulating an HMP requires making assumptions along several dimensions. To organize our analysis, we make a group of assumptions about program design and behavioral responses that we will collectively refer to as our reference HMP. We will then run simulations after changing program design features one by one to look at the relative change in HMP success. A simple description of the computational approach is that based on the housing supply in targeted destination tracts, we first determine the number of movers that can move to a new tract in an HMP of a given size. We then select that number of movers from origin tracts and move them to destination tracts. That is, we simply subtract program participants from the population counts in origin tracts and add them to the population counts in destination tracts. Our simulations allow us to quantify how residential segregation would change under various definitions of origin and destination tracts that represent various program design features.”

- “Fig. 11(a) shows the result of the reference HMP in Baltimore. The CDF of poor Black residents shifts to the right much more than does the CDF of poor white residents, so that our measure of racial equality increases from 38 to 48. As suggested by Fig. 10, Table 1 confirms that this greater shift for Black poor residents is due to the over-representation of poor Black residents in areas of concentrated poverty. Also suggested by Fig. 10 and confirmed in Table 1 is that different racial and ethnic groups will be affected depending on the metro.”

- “Fig. 11(b) shows the result of the reference HMP in all of the 54 large metros in our sample. The x-axis in the figure shows racial equality as measured in the current data, and the y-axis shows racial equality in the metro after implementation of the baseline HMP. All metros are above the 45 degree line, meaning there were increases in racial equality. A few cities are highlighted due to their prominent HMPs or early adoption of SAFMRs.”

Figure 11. Results of the reference housing mobility program

- “Fig. 11(b) makes an important point about the magnitude of effects from HMPs. If HMPs are designed at a small scale to avoid endogenous sorting responses by incumbents so as to maintain current neighborhood effects (Agostinelli et al., 2020, Agostinelli et al., 2021), they will not by themselves entirely create racial equality in the neighborhoods of poor Black and white residents. HMPs are a powerful tool for generating racial equality of opportunity through neighborhood effects, but HMPs are one part of the larger changes in our society that would be required to achieve racial equality.”

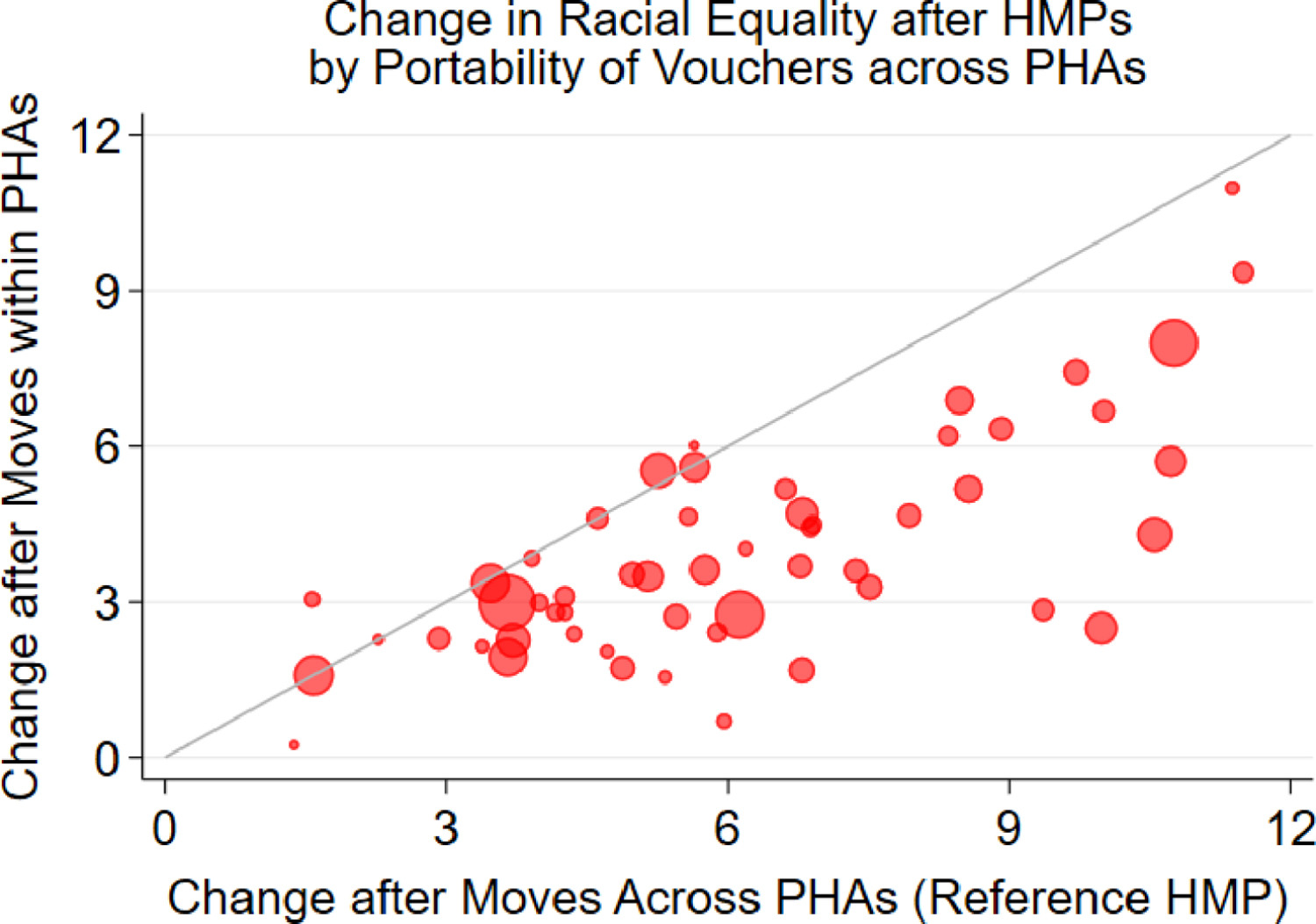

- “Housing choice vouchers can technically be used in the jurisdiction of any PHA in the US. However, due to the administrative burden it creates for PHAs (Greenlee, 2011), such “porting” of vouchers across PHA boundaries is rare in practice, with voucher holders almost always leasing up in the jurisdiction of the PHA that awarded their voucher. Nationally, the percentage of voucher moves that involved porting was 1.6 percent in 2005 (Climaco et al., 2008).”

- “Given the potential importance of regional partnerships allowing for voucher holders to easily port their vouchers across PHA boundaries, we simulate a version of the baseline HMP with no porting across PHAs … Fig. 12 shows the results of the “No Porting” HMP. We see that in many metros the effectiveness of the HMP falls considerably. These results quantify the benefits of forming regional partnerships (Scott et al., 2013).”

Figure 12. No porting HMPs

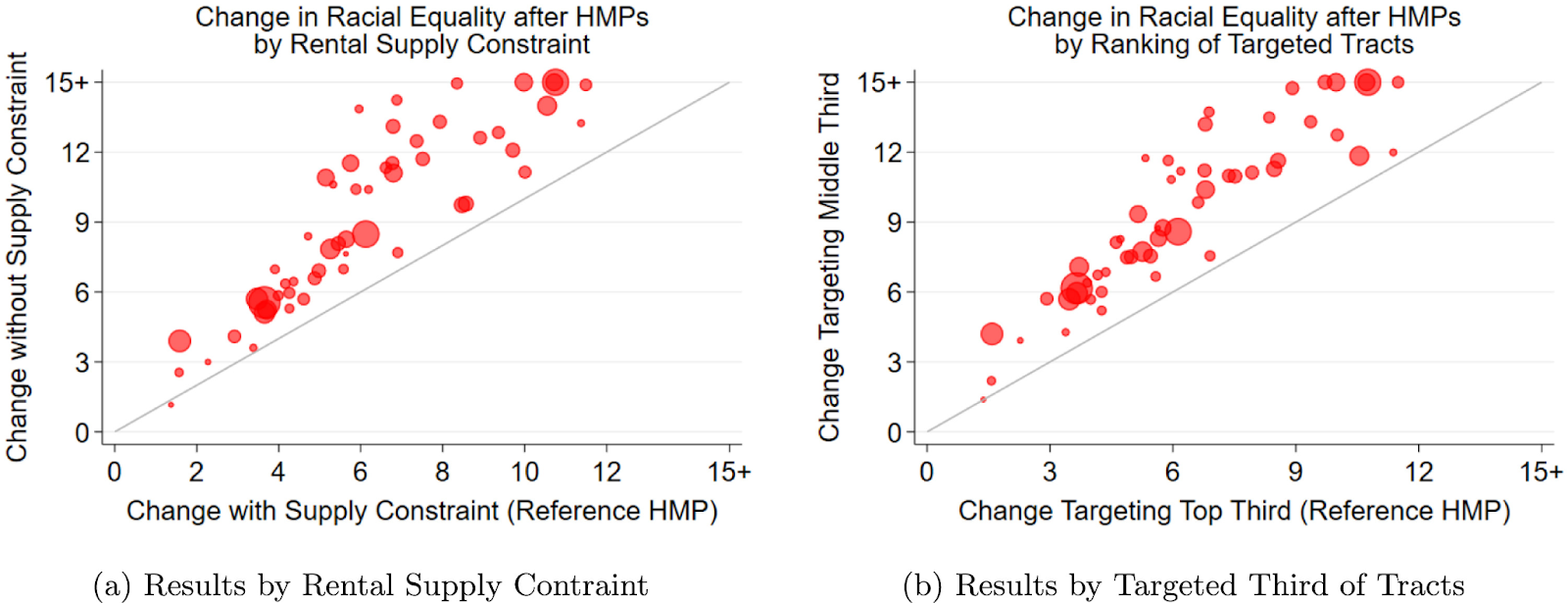

- “The supply of rental housing is one of the most important constraints HMP practitioners face … Supply constraints can be especially binding for voucher holders due to barriers that limit supply like search costs, information frictions (Bergman et al., 2020a), and landlord avoidance of voucher holders (Phillips, 2017, Aliprantis et al., 2022b). Some PHA-provided services can therefore relax supply constraints, with housing search assistance and landlord outreach being two key services provided by the BHMP (Cossyleon et al., 2020). But such services are not always given priority when implementing housing programs (Popkin et al., 2003). Should they be? And are there any other strategies for expanding the supply of rental housing available to HMP participants?”

- “Fig. 13(a) shows the results of the reference HMP altered so that families move uniformly to all targeted neighborhoods, regardless of each neighborhood’s supply of rental housing. The metros all being located well above the 45 degree line indicates that relaxing the supply constraint has a major effect on the success of the HMPs.”

- “Fig. 13(b) shows an approach to relaxing supply constraints; targeting lower-ranked tracts with a greater supply of rental units.18 We find that targeting the middle third of tracts as opposed to the top third of tracts actually reduces racial inequality much more than the baseline HMP; generating as much improvement as eliminating the supply constraint. Table 2 helps explain the results of this HMP. In most cities, the share of supply-constrained tracts is much higher in the top third of tracts than it is in the bottom third of tracts. The resulting supply of units in the middle third of tracts is higher than in the top third of tracts.”

Figure 13. Relaxing housing supply constraints

- “In general, geographic mobility may be a less important spatial friction than information and referral networks (Schmutz and Sidibé, 2019, Heise and Porzio, 2021, Miller and Schmutte, 2021). However, in the context of low-income Americans residing in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, access to transportation, especially an automobile, could play a relatively large role in accessing economic opportunity (Gobillon et al., 2007) … We assess the importance of access to a car by conducting an HMP that modifies the reference HMP to only target tracts with access to public transportation … We define a tract as having access to public transit if its centroid is within half a mile of a transit stop.”

- “Fig. 14(a) shows that access to public transportation tends to be negatively correlated with neighborhood quality, and that there is considerable variation across metros in the strength and levels of this relationship … Fig. 14(b) shows that the effect on racial equality plummets when HMP participants only move to transit-accessible tracts. Given the massive decline when only moving to accessible tracts, along with the fact that it is not clear that access to public transportation is sufficient for access to employment (Sanchez et al., 2004, Smart and Klein, 2020), suggests that supplementing program design with access to cars could improve the success of HMPs (Pendall et al., 2016).”

Figure 14. Access to public transportation

- “The US Supreme Court’s interpretation of the US Constitution is constantly evolving, and the history of interpretation with respect to race is full of major changes. Thus, while the current legal precedent would indicate that designing an HMP that targeted only Black participants would be unconstitutional, one could imagine a change in interpretation that would render such a policy legal. What would be the implications of an HMP designed explicitly around race and Black participants? …Fig. 15 shows that an HMP targeting only Black participants would have a substantially larger impact on racial equality than the race-neutral reference HMP.”

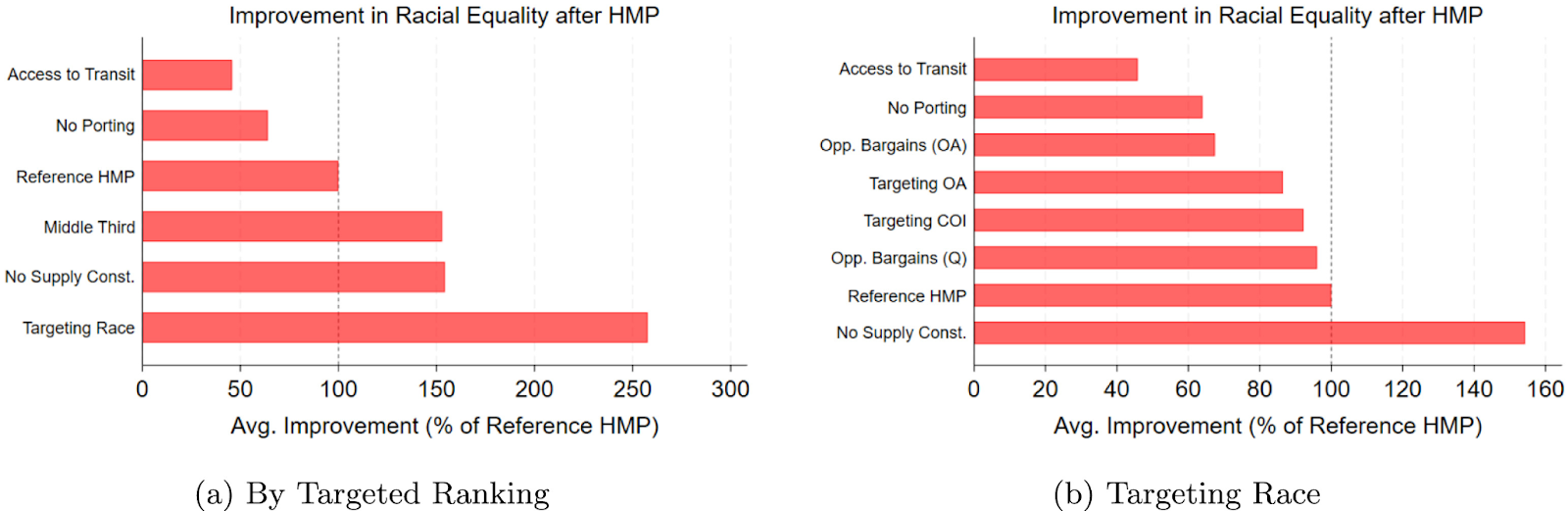

- “Fig. 16(a) plots the results for the reference HMP along with several HMPs examined earlier that differ in one design feature relative to the reference HMP.”

Figure 16. Average improvement in racial equality across all metros

Shane Phillips 0:04

Hello, this is the UCLA Housing Voice podcast, and I'm your host, Shane Phillips. This week, we're joined by Dionissi Aliprantis to share his research on housing mobility programs, which use rent assistance vouchers to help lower income households move to higher opportunity neighborhoods.

This is the first of two consecutive episodes on the housing choice voucher program. As we discuss in the interview, the paper really has two aims, only one of which is obvious from the title. The first purpose is outlining three different ways we commonly measure neighborhood opportunity, and challenging one in particular, the opportunity atlas, which has real strengths, but also some possibly underappreciated shortcomings. Compared to the other two measures, the atlas often comes to very different conclusions about which neighborhoods offer residents the best opportunities for making a better life. This may seem like a purely academic question, but it does have serious real world implications. Housing mobility programs, or HMPs, are all about helping people move to better neighborhoods. If one measure says a neighborhood is in the top third, but another says that same neighborhood is in the bottom third, what are we supposed to do? Do we want to help lower income families move there, or should we be encouraging them to Dionissi and his colleagues build on these insights by modeling HMPs with different characteristics, including changing portability between cities or public housing authority areas, which we talked about in our previous episode with Sarah Strochak, as well as relaxing housing supply constraints and expanding the set of neighborhoods that voucher holders are encouraged to move to, specifically to more middle class areas and not just the wealthier ones. These changes could lead to surprisingly large reductions in racial segregation, and some changes could be implemented pretty fast. There was a lot about this paper and conversation that surprised me, and unless you know as much about vouchers, neighborhood opportunity, and segregation as Dionissi does, you will probably have a similar experience. So enjoy.

The Housing Voice podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies with production support from Claudia Bustamante, Irene Marie Cruise, and Tiffany Lieu.

Be sure to share the show with your network and send your questions and feedback to shanephilips@ucla.edu. And a reminder for the accredited planners out there, do not forget that you can get AICP credit by listening to the show.

With that, let's get to our conversation with the Dionissi Aliprantis. Dionissi Aliprantis is a researcher at ENS de Leon with a PhD in economics from the University of Pennsylvania, and he's here to share his research on how housing mobility programs, which help people move to better and less segregated neighborhoods, can be redesigned to improve participant outcomes. Dionissi, thanks for joining us and welcome to the Housing Voice podcast. Happy to be here. Thanks for having me. And my co-host today is Paavo, also in Lyon or maybe in Paris right now, hey Paavo.

Paavo Monkkonen 3:15

Also in Lyon, hey Shane and hey Dionissi, it's great to see you. Just a little behind the curtains, I think we talked about maybe Mike Lenz co-hosting because he's a resident housing choice voucher expert, but I'm excited that it's me, not only because Dionissi and I are fellow Liene these days, but also because this paper might seem like a technical and policy relevant in-depth research study, which it is, but it's also a pretty exciting kind of shots fired drama paper, so we'll get into that. I'm looking forward to hearing kind of some of the political fallout potential after you publish this.

Shane Phillips 3:50

Yeah. Tackling a pretty big name in the industry. Yeah. Okay. So as always, we first ask for a virtual tour of a place you know well and want to introduce our listeners to, so Dionissi, where are you taking us?

Dionissi Aliprantis 4:06

So I was thinking about this and as the parent of a couple small children at this point, my life isn't so exciting, but something that is that Pavo can maybe add on to is that, you know, I just moved to Lyon, France. It's quite interesting place, so I was thinking I would maybe take you to Quaroos. So it's an area of Lyon with a lot of like a lot of steep inclines, so it looks over the city and is really nice.

Shane Phillips 4:32

Also famously great for children.

Dionissi Aliprantis 4:34

Yeah, exactly. I'm sure they love that. They love stairs. Yes. Always good. Always good. We went for a nice dinner at a restaurant there over the winter holiday and it was kind of funny because the upstairs was maybe, I don't know, maybe five feet tall like this. So, for me being over six feet tall and for someone like Pavo, it was just, it ended up being really cute, really nice ambiance, but you know, when you're getting in, you have to be a little bit careful. That's what happens with these old buildings and nearby, another place that's very cool is Vue Lyon, so like old Lyon. Something interesting there, so they have these like traboules, these like little passages, interesting little tours, all these little passages between all the old homes and something that's kind of interesting about it, speaking of Jeff Lynn's work, is that actually apparently they wanted to demolish the area and or the mayor at some point wanted to demolish the area and put in a freeway.

Paavo Monkkonen 5:35

Louis Pradel, yeah, famously after he went to LA, he got so excited. Couldn't contain his excitement for it, huh?

Dionissi Aliprantis 5:40

So, yeah, so that's just something that, you know, whenever I'm over there and walking around and just there's so much character, it's so nice to just walk around. I guess it had fallen into a little bit of disrepair at the time, so that was part of the reason too, but the point is they rehabbed it and now everything over there is just kind of amazing and it's really incredible. It's kind of like, you know, times that I've been in San Francisco on the wharf and you're like, oh man, really? Like they wanted to put in a freeway here? Like really? Like, oh man. So yeah, so that's Lyon in a nutshell, a few small places here.

Shane Phillips 6:17

I am also over six feet tall and I've experienced this in other countries, some Mexico City basements, some parts of Tokyo. I mean, you get it here even in the US in the older housing, if it's like a hundred plus years old where the door frame might be like six feet tall or so. Yeah, it's just what you get with an old place, I guess. People didn't get enough nutrition back in the day.

Dionissi Aliprantis 6:40

Well, and the thing I love about it here though is we were talking about it over dinner that just there's like, okay, well we'll just use that space and actually add some charm. Like it's all good. We'll make it work.

Shane Phillips 6:50

There's an episode maybe of 99% Invisible or some other show on like the old maid's quarters in Paris.

Paavo Monkkonen 6:58

Chambre de Beaune, yeah, it's fantastic.

Shane Phillips 7:01

Sounds a little bit like that to some extent, especially if it's at the top floor.

Paavo Monkkonen 7:05

I think, well, these are older because those are like 19th century. I mean, the Croix-Rouce is like 18th century, the silk workers. That's the cool thing about the Croix-Rouce too is that it's like the revolutionary hill. I think it was the first union in France was the silk workers union of the Corbus and so part of the thing about those passages through the buildings is like, I don't know whether it's true or not but what I've heard from lefties is like, oh, they use them to like sneak away when they're fighting the conservative forces trying to oppress the union or whatever. But yeah, I was with some city of Paris people the other day and I was talking about micro units and how the shock of Americans to consider having micro units of 200 square feet and yeah, the minimum size now legally is I think 9 square meters or maybe 9.5 square meters. Just about 100 square feet. Yeah, that's like the minimum. But that episode was good because they go into the cost. I mean, it's like, yeah, it would be nice to have a bigger place but for these young people during the time in their life, they really are able to take advantage of the city by having that lower rent, very small place to live.

Shane Phillips 8:11

Yeah, yeah. I think we've talked about it in here before and I've mentioned it elsewhere many times. It's all well and good if you're saying people deserve better but if all you're doing is taking away an option and not providing resources for people to afford the higher quality options that you now raise the standard to, then you might actually be harming people and so how you balance that is a really tough challenge because it's obviously coming from a good place. So like the study from our last episode, which is not out at the time of this recording, so neither of you know anything about it, this one is on housing vouchers and was published in the Journal of Housing Economics. It's from September 2024 and titled What Determines the Success of Housing Mobility Programs? With co-authors Hal Martin and Kristin Tauber, housing mobility programs in the US are sort of a specific application of housing vouchers and housing vouchers help lower income people pay for rent in the private rental housing market. We talked about vouchers in our previous episode with Sarah Strochak as well as in episodes 17 and 64 for anyone looking to learn a little bit more. Housing mobility programs supplement vouchers with other tools and assistance to help people move to higher opportunity neighborhoods, which could be places with lower poverty rates or that are less racially segregated. Another one of our previous episodes, number 58 with Craig Pollock, is about the public health impacts of one such HMP, the Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership, and just a heads up, we will refer to housing mobility programs as HMPs throughout this conversation. As I understand it from the article, there have been four big HMPs in the US and they've had quite different levels of success. And in this research, Dionissi and his colleagues explore how the design of these programs might lead to better or worse outcomes with respect to reducing racial segregation and specifically segregation of black households into different and usually quite a bit poorer neighborhoods from white households. By simulating programs with different characteristics, things like restricting voucher holders to census tracts with access to public transit or enabling people to use their vouchers in jurisdictions other than the ones that issued them, or at least making that realistic to do, they find that program design of HMPs can have a pretty significant impact on desegregating cities. Given that tenant-based vouchers are really one of the only US housing programs specifically focused on integrating cities socioeconomically and at least indirectly integrating them racially and ethically, that is a pretty big deal. Dionissi, let's start with more background on housing mobility programs. What's their history in the US and what can you tell us about the goals and relative success of the four that you discuss in the article? And maybe correct me if I'm wrong that those are the only big four.

Dionissi Aliprantis 11:02

Yeah, sure. So I guess I would start by saying that, you know, this thinking about the Housing Choice Voucher Program a little bit more generally and thinking about encouraging moves to opportunity areas is something that's kind of receiving a lot more attention right now. I would say for good reason, there's a lot of good things coming out of that. And so in this paper, we're thinking a little bit more traditionally though about housing mobility programs that were kind of some of the inspiration for some of these policy changes. And these housing mobility programs really started with the Gautreaux program. So that started in 1976 in Chicago and I guess what I would say is I would recommend to – if anyone's interested in any of these topics, I guess if you're listening to this point, you would probably really enjoy the book Waiting for Gautreaux. And yeah, people either get that joke or don't. I was in the crowd that would not have gotten it before reading the book. So it's written by the lawyer who actually argued this case, took 10 years. He started in 1966, went all the way to the Supreme Court and you know, the whole idea, the basic premise of it was look, we said that public schools in our country shouldn't be segregated by race, at least not legally. And so our public housing shouldn't be either. And it turns out, I mean there were whistleblowers, you could talk to alderman and all this kind of thing. But at some point you just look at a map and you look at where units were being constructed in Chicago, public housing units. And you could see that public policy, you know, the government was helping to residentially segregate the country by race.

Shane Phillips 12:36

Was that argument really about housing or was it also about schools? Was it saying, you know, we don't segregate schools and so we shouldn't segregate housing either? Or was it we don't segregate schools but if we segregate housing, we're going to de facto segregate schools anyway so we have to resolve that for the benefit of schools?

Dionissi Aliprantis 12:56

I think it was more that these were separate issues but it's funny you bring that up because it's an issue that I personally think does not get nearly as much attention as it should. That issue that you just raised is a huge issue and you know, going back to the 50s and 60s, you had people like NAACP, Robert Weaver, you know, lots of black leaders that were very concerned about just that issue. Again, it's, you know, just this whole issue of residential segregation is one that in a lot of ways, I don't think we've really solved. So the thing that's interesting about Gautreaux is that it turns out that Mitt Romney's father, George Romney, was the secretary of HUD under Richard Nixon and you know, the section eight voucher program, the precursor to the housing choice voucher program, the section eight program was new in the 70s. I think it started in 74 so it was a new program. People didn't really know much about it. You know, people were thinking creatively about how we might be able to use these programs and you know, George Romney wanted to desegregate the whole country using these programs. He saw how successful it was in Chicago and he thought, look, this is going to be great. Okay, so George Romney lost. He lost that internal debate within the Republican Party and the Nixon administration. Right, kind of pushed out of the administration. Yeah. But the thing that's interesting is, you know, there's a speech by Richard Nixon which is just super nuanced. I mean, he was thinking about these issues in very nuanced terms. Like he was understanding, you know, well if you give people kind of freedom to go move wherever but they don't have the means, does that really turn into access to opportunity? He actually was very thoughtful about this and you know, thinking about the fact that well, it's not necessarily bad if you have an Italian neighborhood. That can be a really good thing that you know, people are able to support each other. That's not inherently bad that people associate with each other. It's oh, it's when you know, we're thinking about maybe choices being restricted or resources being restricted. That's the issue. So, the history of this is very interesting but when this was employed in Chicago through Gautreaux, it was wildly successful. If you read the ethnography, you know, I find it quite emotional to read the ethnography because you do have, you know, initially you have this kind of, you do have some hostility and you do have some discrimination but at some point, people end up baking cakes and bringing them over, kids start playing and you know, people make friends and I don't think it's entirely perfect but given where it started from, like I'll take it. I think it had some really positive effects and I think you know, the thing about Gautreaux and that kind of leads into moving to opportunity, there's a number of things about the program and housing mobility programs in general that are you know, really lend themselves to bipartisan support. So, when you're thinking about moving to opportunity, which was modeled off of Gautreaux and it was very heavily influenced by the work of this sociologist William Julius Wilson, also just you know, research in general at the time thinking about concentrated poverty and thinking about why are we really worried about residential segregation, why are we worried about kind of neighborhood effects and it's really this issue of when you get concentrated poverty that we want to break that up. So, moving to opportunity was designed kind of as the next step from Gautreaux. Gautreaux was in a lot of ways a quasi experiment, we can talk about how people are actually allocated to different units. One group of people were allocated to kind of suburban neighborhoods that were less than 30% black, less than 5% with vouchers and another group was assigned to units within the city that were forecast to undergo some kind of revitalization. And we can talk about you know, how random it was or was not that people were kind of put to the top of the list and given a unit, I think it's about as good as you're gonna get personally from what I've read. But MTO, the idea was we're gonna actually run an experiment, we're actually gonna go in and we're gonna randomize who gets a voucher that says you know, you need to move to a tract, a census tract with less than 10% poverty which was the median poverty rate. This happened in the 1990s and then there's gonna be a group that's just gonna get a standard Section 8 voucher and a group that's gonna get you know, kind of place-based assistance, continued assistance.

Shane Phillips 17:00

And the people who get just the voucher, they're free to move to a neighborhood with less than 10% poverty but they're not required to.

Dionissi Aliprantis 17:07

Correct, correct. They could. And so yeah. And in practice, they rarely do. Yeah, they rarely do. And I mean, yeah, we can talk about the design of MTO. I mean, there's a lot to talk about.

Shane Phillips 17:18

We've talked about that I think in prior episodes and maybe our one with Rob Collinson might be the best one for detail on that. But just to you know, add that context.

Dionissi Aliprantis 17:29

Yeah. So I mean, so I'll just say one quick note about MTO and HMPs in general, I have a feeling I might come back to it but there's a couple of things that make it appealing kind of across the spectrum. So one is we don't necessarily have a lot of policy tools that help us really effectively combat generational poverty. It looks like HMPs are one. It's kind of a big deal. So that's one thing. Another thing is it's something Democrats tend to like it because you're helping kind of lower income people. Republicans tend to like it because you're using the open market, you're using housing vouchers on the market. And something that for me, I think in some kind of conservative sense of the word in terms of like moving slowly, I actually think a very appealing part of housing mobility programs is that they can be scaled up and scaled back. So this is something that we'll talk about some of the assumptions in some of our simulations but you might be worried that, you know, there might be too many people moving and it's going to change the character say or the composition of a receiving neighborhood and there's going to be incumbent response so people in the receiving neighborhoods might move away. There's a really, really easy and effective way to deal with that with these programs. So the thing is just start really slow. Don't send many people. It can go very slow and you can ramp it up and if something happens and it turns out, you know what, the program is too big and it's having too big of an effect, you can just slow things down. Like you can actually adjust on the fly and I think that's a really big deal especially when you think about politically actually implementing these.

Shane Phillips 18:58

Yeah. I mean on the flip side, you can ramp it up much more quickly than building homes for example as well and so the opposite is also true if that's your goal or, you know, depending on your circumstances.

Paavo Monkkonen 19:08

Well, if there are rental units available as we'll get into. Yes.

Shane Phillips 19:11

Yes. Minor detail.

Paavo Monkkonen 19:15

Minor detail. Speaking of supply.

Dionissi Aliprantis 19:16

Yeah. So a couple of things to say about MTO, I mean we'll get into MTO but I think one important detail about MTO is that I guess HUD, I think they had actually funding something like nine or maybe it was even like – they had funding for many sites. Only five cities actually took up that funding. So I think that already is telling you something. So those places were Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, LA and New York. And so this was done in the mid-90s, you know, actually ran the experiment. Then the other two that we talk about a lot are the Baltimore housing mobility program. It's administered by the Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership. Also very like same legal precedent in this Thompson ruling started in the early aughts and the Creating Moves to Opportunity program which kind of a follow-up to MTO run very recently by the Opportunity Insights team from Harvard actually implemented in Seattle. And there have been other housing mobility programs, actually like a lot. So there's been versions of this say in Dallas, the Inclusive Communities Project. There have been a lot of other programs but these are in some senses the largest and also the best study. So we've actually looked at these very carefully. A lot of people have thought about them, a lot of people have written studies, looked at the data and so these are the ones. We focus on these because they're I guess kind of maybe the canonical and best known HMPs.

Shane Phillips 20:41

This is a totally unimportant question but having two researchers here who are currently based in France and from the U.S., what is the deal with Gautreux's name? It's a very French name for a 1970s U.S. housing mobility program.

Dionissi Aliprantis 20:57

So it was named after Dorothy Gautreux.

Shane Phillips 21:01

Okay and this is G-A-U-T-R-E-U-X. So very French word. It's E-A-U-X. You can tell I do not know how to…

Dionissi Aliprantis 21:13

Yeah, me neither. My written French is quite poor actually at the moment. So yeah, it was actually one of the residents, a public housing resident who brought the case. Oh, I see. Who initiated everything.

Shane Phillips 21:27

That makes sense. All right, well I think our focus in this interview will be on the HMP simulations that we put together which we'll talk more about and how program design affects racial equality. But the first half of the article is really more about the different ways we rank neighborhoods for the purpose of identifying high opportunity neighborhoods where we want to encourage people to move in these kinds of programs. Could you just describe the three ranking metrics discussed in the article, neighborhood quality, the childhood opportunity index, and the opportunity atlas, and then what distinguishes them from each other?

Dionissi Aliprantis 22:03

Yes, I can tell you a little bit about these measures. So we use one measure that we refer to as neighborhood quality and some other work of mine we refer to it as neighborhood socioeconomic status or neighborhood SES. It's just a measure that combines six variables measuring the socioeconomic status of current residents. These are characteristics of a census tract of a neighborhood that we think might have some effect say on labor market outcomes whether of current residents or of children in the future. And so these are things like educational attainment, labor market outcomes, share of households with children that are single-headed, and the poverty rate, something about income. So that measure, the kind of virtue of that measure is that it's very quick and easy to put it together. So you're just taking the first principle component, you know, it's a very quick simple statistical thing that you would do to put this together. It's easy to get the data and it's a quick simple summary of kind of what's going on in neighborhoods. It's a quick easy way to rank neighborhoods.

Shane Phillips 23:03

Right. You can get all of that data from the American Community Survey, just one source that's updated annually.

Dionissi Aliprantis 23:09

Correct. And so that's something nice about it. The childhood opportunity index is an index that's been put together by a group of researchers. I believe they were based at Ohio State at the time and I should figure out where they are now. But the childhood opportunity index, in some senses it's similar to the neighborhood quality index, in that it's measuring kind of current residence socioeconomic status, things along those lines. But now they've expanded it to 29 variables. And so the virtue of that is you're going to get a lot more information. So now you have things like test scores in the schools, you have environmental quality, you have, you know, all these other variables that you think really matter for the people that are living in neighborhoods that might have an effect on them. The drawback though is that because you have so many more variables, it's going to take time for those variables to be collected, to be measured. You're going to have to go to different sources to incorporate them. But it's the same idea of just, you know, putting all of these different dimensions into one dimension and then ranking neighborhoods according to that dimension. So in some senses, you know, these are pretty similar, just kind of philosophically or in terms of construction. And so, you know, the first part of the paper is trying to think about this new measure that just came out called the Opportunity Atlas. And it's a pretty remarkable just kind of feat that they were able – so this is again from the Opportunity Insights team at Harvard. They were able to link census records with IRS data and were actually able to, you know, kind of look at how kids in specific neighborhoods, how they did in adulthood. And you could look at kind of their parental income in childhood, things like that. You can look at their race, you can look at their gender. So there's this new resolution and this new kind of set of variables that we've never had before that we can use to think about neighborhoods. And those variables in that data set, they've been used to think about housing mobility programs and public housing. So we wanted to kind of kick the tires and get a sense of, you know, what's going on with these data. And so we started comparing these different measures and thinking about how much these matter. You know, it's funny because the way we titled the paper, in fact, it's – I don't want to say it's totally ridiculous, it's a little bit ridiculous in the sense that we kind of actually already know the answer. So you know, go ask Stephanie DeLuca at Johns Hopkins, go ask, you know, Phil Garboden. They've done a lot of work on the BRHP already and they can kind of tell you. You know, and Stephanie was on the Creating Moves to Opportunity team, really nice insights. You know, but we already know that things like landlord outreach, pre-move, tenant counseling, post-move, tenant counseling or tenant support, housing search assistance, small area fair market rent, so having rents that will actually, you know, kind of pay more in these higher income or higher rent areas. We know that those things are actually really effective and they have been for the BRHP. But then you might ask, okay, well, some of these measures disagree. You know, if you're designing a housing mobility program, you might say kind of the canonical way of thinking about it right now is, okay, we would encourage people to move to the top third of neighborhoods or census tracts in a metro area. And you say, okay, well, how much do these disagree? So we focused a lot on Baltimore, given its history with these, with the BRHP. And there's 671 census tracts in Baltimore and the Opportunity Atlas and neighborhood quality disagree on 140 tracts, whether they are in or out of the top third. So that's a lot.

Paavo Monkkonen 26:45

That is a lot, yes. That's a lot, especially because, I mean, the top third is already a lot, so. Exactly. And so then – 140 is almost a third.

Dionissi Aliprantis 26:52

A hundred – it's a lot. So then the question becomes like very practically, you pull up a map and you look at the census tracts and you look at the ones, you know, favored by one measure or another and you start saying like very practically, like imagine Shane Pavo. Imagine we are a public housing authority or we're a, you know, an administrator like the BRHP, we are running an HMP. We look at that map, at those statistics and we see that disagreement, how do we interpret it and how big of a deal is that? Like should we have some knockdown drag out fight that like, you know, it has to be the childhood opportunity index. That's the one that's, you know, really going to make all the difference. So that was kind of our first question. So also there's different levels of disagreement. So the childhood opportunity index and neighborhood quality disagree on a lot less. They disagree on 71 tracks on their categorization and being the top third or not. And so then there's this question of like how should we interpret that extra variation and that extra disagreement in the opportunity atlas? Like it's clear that because it's based on actual measurements in some sense of like people's outcomes, we suspect and actually we've done some statistical tests and other, you know, the team there that released the data is presented evidence as well, that there's information about neighborhood effects in that data set that was useful and like above kind of what you would get just from looking at kind of current residents. That being said, it is based off of measurements for people that lived in those neighborhoods two decades plus ago. So neighborhoods evolve over time, they change and also they are their estimates. And so, you know, they're based on a sample and then, you know, there's uncertainty that comes along there. And so then the question becomes how strongly do we interpret that disagreement? How important is it and how big of a deal should we make out of that?

Shane Phillips 28:40

So I mean it's really about for these HMPs, for the public housing authorities, we don't necessarily know where we want to send people if we don't really have some certainty about what constitutes a high opportunity neighborhood and these different measures that are kind of the common metrics for identifying high opportunity neighborhoods just have a lot of disagreement. It sounds like actually within the top third, it sounds like about two thirds of that there is disagreement between the opportunity atlas and the neighborhood quality metric. But even between the neighborhood quality and childhood opportunity, about a third of tracks in the top third are, you know, they disagree on that. So there's just a lot of uncertainty.

Dionissi Aliprantis 29:20

There's a lot of uncertainty. And the thing is the disagreements between childhood opportunity index and neighborhood quality are relatively small in nature.

Shane Phillips 29:30

So it might be like the COI puts the neighborhood at the 75th percentile and the neighborhood quality puts it at 60th, whereas the opportunity atlas might put it at like 90th or 20th or something. That's an extreme example just to illustrate.

Dionissi Aliprantis 29:44

Well no, that's exactly right. And the point is those neighborhoods exist. So there's neighborhoods that if you're using neighborhood quality, you might say actually this is one of the best neighborhoods in America for a kid to grow up in. And the opportunity atlas would say actually this is one of the worst or vice versa.

Paavo Monkkonen 29:59

And it's that extreme? I thought it was just, you know, is it in the top third or in the middle third rather than top and bottom?

Dionissi Aliprantis 30:06

So then we – motivated I guess by this disagreement about the top third, we started doing some statistical analysis. And this is one of the things that you see is that's not super common, but it exists. So you might see a track where it's like they're ranked very differently. And so the question is how do you interpret that? Is that kind of unambiguous signal that like, hey, there's some neighborhood effect here we really need to pick up on or could it be something else? And so some of the things we found is when we were looking around at that, one of the things is in some tracks, in tracks where there were big changes in population, those were also the tracks where essentially big disagreements between quality and the opportunity atlas are very predictive of big changes in population. And so this is something where you start saying, well, maybe the reason they disagree is because the residents of the tract have changed a lot since the time when the opportunity atlas sample was there. And another place where they disagree a lot are places where the number of children growing up in that tract, so kind of the sample on which you would estimate future outcomes is actually very small. So that's a place you see that there's a lot more disagreement when the samples are smaller. So kind of statistical noise. So the thing is we looked at that and kind of the takeaway that we found was when you take out the tracts where there's either big changes in population, and so you're kind of a little bit suspicious, or tracts where the sample was relatively small, then all of a sudden the opportunity atlas and neighborhood qualities, then their disagreements start looking a lot more like the childhood opportunity index and neighborhood quality, those kinds of disagreements where they broadly agree there's some disagreement, but there aren't these really strong outliers. So that suggests to us that most likely, you know, some of these measurement issues are kind of driving some of that disagreement. And you know, when you look at what the Opportunity Insights team did when they actually ran the CMTO experiment in Seattle, they were very conscious of this and they did a lot of adjustments along these ways. So they adjusted for, you know, kind of more current outcomes and more current resident characteristics. So they were thoughtful and they did a lot of these things, but I guess the point from our analysis is that it seems like that's actually really important. It seems like some of that disagreement is coming from kind of measurement issues.

Paavo Monkkonen 32:21

Yeah, I found this section super interesting as somewhat of a index nerd myself, having been in some debates over the opportunity index that the California state government uses to guide some of the affordable housing investment decisions. I think it's a very fascinating arena. And I mean, I'll just for people that aren't as well versed in this, I want to just give them some of the interesting political dynamics behind this is that, I mean, the Harvard Opportunity Insights team led by Raj Chetty got extremely famous and because of this important insight that they had and this ability to connect the tax data and to be able to show the factors that are actually leading to people doing better later in life, right? And so previously we were making assumptions that better schools and rich neighbors and better public service, I mean, not unreasonable assumptions that those features are going to have long-term effects, but they're able to show that they did. And what you're pointing out is that you're not disagreeing with their findings in that sense, but you're saying to use those index values now is problematic because those things change over time, right? At the neighborhood level, is that a more or less accurate summary?

Dionissi Aliprantis 33:28

So that is an accurate summary. I would give a little nuance in the sense of, I would say that there remains this very tricky question of causality and that is people choose their neighborhoods. And so even when we observe that kids growing up in a neighborhood do well later on, do we know that it was because they were in the neighborhood and exposed to the kind of higher socioeconomic status or the environmental quality? Maybe they weren't exposed to pollutants or maybe there's a million other things that could be going on. And so the tricky thing is there is this issue about causation and causality that is quite tricky, but I think the thing is that these data do give us a new window on that. And so that's, I still think quite exciting and there's new evidence. So there's a number of findings in the research on the opportunity atlas that are quite interesting along these dimensions, but fundamentally there still is this very difficult problem of how do we assess how much of those differences in outcomes is due to the neighborhoods versus, for example, the parental education of the kids that were growing up there.

Paavo Monkkonen 34:39

Right. And I like the way you, I mean, I think your proposal to use why not both and kind of blend the two and, you know, in neighborhoods where we know that the opportunity atlas might be less effective, we weight the more current data based atlases more. I mean, that seems like a really smart way to handle this. I know Shane wants to get into the policy and get off the next talk, but I did want to point out there's this nice piece on the opportunity bargains neighborhoods, which I learned about from Mike Lance, which I think is a great topic. Maybe just like what's the opportunity bargain neighborhood. Sounds great.

Dionissi Aliprantis 35:11

So an opportunity bargain, yeah, you want, you want one? I got one for you. So no, so the idea here is the question is, can we find areas, can we find census tracts neighborhoods where actually growing up there or, you know, living there now would have a really positive and beneficial effect on somebody moving there, but the rent is relatively low and the rent might be relatively low for any number of reasons. Most likely there's some kind of information friction or, you know, whatever it is, people value something else about the neighborhood or other neighborhoods. There's something about the market where actually the price isn't totally conveying the information about what it is to live in that neighborhood. Part of that could just be, you know, it's actually really hard to know. I mean, as someone that just moved to a new city and you're trying to think of like, okay, wait, where do I move? Where do I send my kids to school? You know, it can be very tricky. And so maybe there are these locations where price is kind of missing some information. And one of the things that we found is that I think there's definitely the possibility of opportunity bargains. I think they could very likely be there. And I think the opportunity atlas could potentially help us identify those areas. But one of the issues is it's a little bit tricky to put too much weight on the opportunity atlas and finding those. And the reason is what we found is if you're looking at tracks that are kind of highly ranked but also kind of low priced, when you start looking at those tracks, what you find is that those are tracks where there's actually, again, these really large disagreements between say quality and the opportunity atlas. And so it kind of makes you start wondering, is this a track that's changed a lot over time? And that the price actually is conveying some information to me that... Right.

Shane Phillips 36:55

The time factor seems really important here where you're looking at kids who grew up in the 90s or so, and maybe it was a great neighborhood for them at the time, but maybe it's changed a lot and is not such a great neighborhood now, and that's why it's more affordable. It's not because it has retained all of those characteristics, but somehow remained or become affordable.

Dionissi Aliprantis 37:17

Yeah. Exactly. And so the finding there is just that, again, this is where being an index nerd and thinking about some of these statistics, it's helpful because it makes us say, okay, this is a tool and we think it can provide us some insight, but we need to be careful exactly kind of how we apply it and how we think about it. So it doesn't mean that I don't think that there are any opportunity bargains out there. It's just, it's going to be tricky to find them and yeah.

Paavo Monkkonen 37:42

And presumably fewer and fewer over the years as information becomes more widely accessible.

Dionissi Aliprantis 37:51

Yeah. But back in the 70s, public government had really good bargains out there. Could sneak in all over the place, right? Yeah. Bargains everywhere.

Shane Phillips 37:55

You know, when I read through this section, I was like, man, this is a lot on indexes and this seems like kind of outside my interests, over my head even. But by the end of the paper, and also I think this conversation has helped me understand better. I think it's worth underlining your point, D&EC, about these are real neighborhoods that we are kind of directing people toward. And whether it's actually a 70th percentile neighborhood in terms of like the opportunities it offers to people and their chances for having a better life than their parents or a 20th or 30th percentile neighborhood, like that actually really does matter. And we want to make sure we're directing people to the former and not the latter. And so, you know, how we measure these things is not some kind of like side issue that is only interesting. Maybe it's only interesting to researchers, but it's not only important to researchers.

Dionissi Aliprantis 38:48

It matters for all of us. It matters for policy. Yeah. We want to get it right.

Shane Phillips 38:51

That's right. This is still not policy, but I think it's worth emphasizing because this paper is ultimately other than the index issues about racial segregation in particular. And as you say in the article, one of the opportunity atlases strengths, this is the Chetty work from Harvard, is that you're supposed to be able to evaluate outcomes by race using this metric, differentiating, for example, outcomes for black boys versus white boys. You make the case that this kind of analysis isn't really possible for HMPs though. And part of your justification, we've talked about this a little bit, comes in the form of this rather depressing passage, quote, at the lowest levels of quality, referring to neighborhood quality, that metric, most tracks have 50 black boys or more with which to estimate outcomes. But once quality gets out of the bottom decile, and this is me saying that's the bottom 10%, back to the quote, the number of black boys is already too low to reliably estimate outcomes in many neighborhoods. That may not make sense upon first hearing it. So can you explain to our listeners what that quote means, both as a statement about the segregation of black people in America generally, and about our ability to measure HMP outcomes by race specifically?

Dionissi Aliprantis 40:07

Yeah, so I think this is an issue that's been coming up in a lot of these discussions about algorithmic fairness and thinking about when you use data from a very unequal or biased society or system, you're probably going to get that back out. There's been an argument of bias in, bias out by some academics. And I think the issue here is, it is quite depressing. And the point is, if we want to answer the question, how would black males do if they had grown up in high income or high SES neighborhoods? Broadly speaking, we don't necessarily know the answer to that question. And the reason we don't know the answer to that question is because we haven't seen it in the data. I mean, we have, but in rare cases. The point is just that that is sufficiently rare and there are sufficient neighborhoods that didn't have a lot of black kids in them in our near past. And in some of them, even now, that it would be hard to say, how would a black kid do growing up there now? And how would it be different than say a white kid growing up there? We don't actually know the answer to that question because we can't just see it. We have to use theory. We have to think about, okay, what are the factors that would maybe make it better or worse for a black or white child growing up there? Again, you have to think about, okay, well, what would their parental income be? What would their parents' educational attainment be? How would that interact with anything else going on in the neighborhood? Maybe a black kid in a high income neighborhood, maybe if it's predominantly white, they might not feel comfortable there. They might have to deal with hostility. And so the broad point is that our society remains and has been so residentially segregated that it's kind of hard to even think about what would our society look like if it were integrated. It's just so far from that, that we kind of have a long way to go. I guess that's kind of a theme that keeps hitting me in my research is just realizing like, oh yeah, we're really pretty far from where we want to be.

Shane Phillips 42:05

Yeah. And as much progress has been made and it is real and important, there's just so much further to go. That's right. Yeah. Well said. I think that sort of leads us to your simulation of an HMP, a housing mobility program. Because as you said, we really can't look at existing neighborhoods to find out what happens to black children in particular, but there's just not enough real world examples of what happens when you put lower income people, lower SES people, people of different races and ethnicities in higher opportunity neighborhoods that tend to be disproportionately white. And so, stepping back here really quick, as a recap from our episode with Sarah Strochak, vouchers are administered by public housing authorities and there are 2200 PHAs in the US, each with its own wait lists and issuing and managing its own vouchers. These vouchers are portable, technically, meaning if I receive one in the city of Los Angeles, then I can use it in neighboring cities like Norwalk or Santa Monica, which each have their own PHAs, as do another 15 or so cities in LA County as well as the county itself. And also, I guess in theory, use it in Fresno or Seattle or Chicago or Miami or St. Louis or what have you. But technically portable, technically is the operative word here because at least as of 2005, which you're just citing a previous study, only about 1.6% of voucher moves involved porting from one jurisdiction to another. You write that this low portability rate is about the administrative burden of actually using vouchers in this way and we don't have to get into that, maybe a topic for another episode. But instead, I just want to use that statistic as the entry point for talking about how the design of housing mobility programs affects where people actually end up moving and the effect that that has on racial segregation. So can you tell us about this reference HMP that you developed and then for the first tweak to its design, describe how much its performance improved by increasing the portability of vouchers.

Dionissi Aliprantis 44:10

So maybe I'll even take a step back if it's all right. Sure. So let's talk about the fact that so there's kind of a lot of heterogeneity across these HMPs in terms of their design, things that you might think of as small differences in design features. There's actually quite a lot of differences across them and there's also kind of quite a lot of heterogeneity in the types of moves that people made in these programs. And so we're kind of trying to understand how do these things connect with each other. And so just as an example, you know, you think about programs like GATRO and the BRHP and these are places where a central part of the program itself is that you can take your voucher and it's, you know, the supports are there for the voucher to be used across jurisdictions. And then something that, you know, we kind of realized, I've been researching moving opportunity for a long time and something we went back and read the actual program manuals as a result of writing this paper and when you actually read the program manuals, you realize, wait a minute, it looks like the vouchers themselves were administered through the central city PHA. And at least in the program manual, it says, well, you know, you can port them. We can help you with that. But it's kind of like a little bit of an afterthought and it just makes you realize, wait a minute, porting could have been this really big obstacle in MTO that maybe we haven't appreciated fully like how it can create a very important obstacle and is that something that really matters? So again, this is something where, you know, we wanted to step back and say, okay, let's just do a kind of accounting exercise. So...

Paavo Monkkonen 45:45

Can I just say real quick? I mean, I think the porting thing is of the different design features you studied. That's the main program design one rather than transit or supply, right? That's the thing that the government could change, you know, most easily, I think. And so extremely important. Do you remember at all the difference in porting rates under these different HMPs?

Dionissi Aliprantis 46:06