Episode 87: Rental Voucher Lease-Up Rates with Sarah Strochak

Episode Summary: Housing Choice vouchers help lower-income tenants pay rent, yet only about 60% of issued vouchers result in a successful lease-up. Sarah Strochak joins to share how lease-up rates vary for different groups and markets, and how reforming voucher policies could improve the lease-up process and get more people into affordable homes.

Abstract: While housing choice vouchers provide significant benefits to households who successfully lease homes with their vouchers, many recipients fail to do so. Understanding more about lease-up rates is critical, yet the latest national study was published over two decades ago and reported on the outcomes of only 2,600 voucher recipients across 48 housing authorities (Finkel and Buron, 2001). We use unique administrative data to estimate voucher lease-up rates and search times for about 85,000 new voucher recipients each year in 433 metropolitan housing authorities for 2015 to 2019, which allows us to explore variation over time, across housing agencies, and across individuals within housing agencies. Overall, only 60 percent of recipients successfully use their vouchers, even after waiting for two and a half years on average to receive them. Consistent with theoretical expectations, we show that lease-up rates are generally lower in markets with lower vacancy rates, more spatial variation in rent levels, and older housing, which may be less able to pass HUD’s quality standards. But we also find considerable variation across individuals within markets. Most notably, perhaps, we find that Black and Hispanic voucher recipients are less likely to lease homes than other recipients in their same markets. We explore mechanisms and find evidence that racial disparities are partly explained by differing conditions in the neighborhoods where voucher recipients start: voucher recipients are less likely to lease-up and take longer to successfully rent homes when they start in neighborhoods with older housing stocks and larger Black and Hispanic population shares. Observed and unobserved neighborhood factors explain about 40 percent of individual racial differences in lease-up rates. We also provide suggestive evidence showing that policy interventions, such as extended search times, neighborhood-based rent ceilings, and source of income discrimination laws, can help both to boost overall lease-up rates and to reduce these racial and spatial disparities.

Show notes:

- Ellen, I. G., O’Regan, K., & Strochak, S. (2024). Race, Space, and Take Up: Explaining housing voucher lease-up rates. Journal of Housing Economics, 63, 101980.

- Episode 17 of UCLA Housing Voice, on Housing Choice Vouchers and small area rents with Rob Collinson.

- Episode 64 of UCLA Housing Voice, on vouchers as a homelessness solution with Beth Shinn (originally aired as episode 21).

- Episode 29 of UCLA Housing Voice, on how landlords make leasing and eviction decisions with Philip Garboden and Eva Rosen.

- LA Times article about the Housing Rights Initiative lawsuit alleging landlords violated source-of-income discrimination laws in California.

- “The housing choice voucher program is the largest rental assistance program in the U.S., providing assistance each year to approximately 2.3 million low-income households (Center for Budget and Policy Priorities 2021). Unlike many federal rental assistance programs, the voucher subsidy is not tied to specific housing units; rather voucher holders use the subsidy to help defray the cost of renting homes on the private market. Voucher recipients generally pay 30 percent of their income towards rent, and the local public housing agency (PHA) pays the balance, up to a specified local payment standard. Research shows that housing vouchers reduce rent burdens, household crowding, and the risk of homelessness (Mills et al., 2006). There is even some evidence that vouchers improve non-housing outcomes, such as children’s school performance (Schwartz et al., 2020), and rigorous evidence that they produce long-run educational and labor market gains, compared to public housing (Chetty et al., 2016).”

- “Yet existing studies and anecdotal accounts suggest that many voucher recipients fail to use their vouchers, in many cases, after waiting for years to receive them. And search times can be lengthy even for those who succeed: it often takes months for voucher recipients to find suitable homes that pass inspection standards and are owned by landlords who are willing to accept vouchers. Finally, certain households, depending on their race and neighborhood environments, may face particularly large barriers to voucher use. So the population benefiting from housing vouchers may differ systematically from the broader low-income population, and may not necessarily be those most in need.”

- “To fully assess the performance of the voucher program, understanding more about contemporary search experiences of voucher recipients is thus critical … The latest study reported on the outcomes of 2609 voucher recipients across 48 PHAs in the year 2000 (Finkel and Buron, 2001). The study found that only about 70 percent of voucher recipients successfully rented a home with vouchers (Finkel and Buron, 2001). A lot has changed in the intervening two decades — most notably, perhaps, housing markets have tightened across the country. Thus it is critical to re-examine voucher search experiences.”

- “Importantly, unlike many other social programs (like TANF or EITC) where benefits go directly to recipients, housing voucher recipients have to secure their subsidies through the private housing market. After receiving a voucher, households have a limited time period during which they must find a willing landlord with an available home that both meets the program’s quality standards and charges a rent that the local housing authority deems reasonable given the local market. The latest national study found that thirty percent of households that received a voucher in 2000 failed to rent a unit in the time frame allowed by the program (Finkel and Buron, 2001). Chyn et al. (2019) find that nearly half of households receiving vouchers in Chicago between 1997 and 2003 did not successfully lease-up.”

- “It is worth emphasizing how surprising these low lease-up rates are. First, voucher subsidies are quite generous. In our sample, the average annual subsidy is about $8000. Second, households receiving vouchers have demonstrated strong interest in the program through an arduous multi-step (and frequently multi-year) process (McCabe, 2023). To start, it is not easy to apply for a voucher. Many large housing agencies only open their application portals every few years for a week or two. There is also no guarantee of receiving a voucher even after applying. Housing assistance is not an entitlement, and waitlists are long. The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that the average voucher recipient in 2020 spent two and a half years waiting for their voucher, and in tight markets like Miami and San Diego, the average wait was eight years (Acosta and Guerrero, 2021). Households that get to the top of the waitlist must provide extensive documentation of their income and family composition.”

- “But actually using a voucher requires that recipients find a suitable unit to rent within the time allowed by the PHA, which must be at least 60 days … In addition to being appropriately sized given household composition, units suitable for voucher holders must charge a rent that falls below voucher program rent ceilings, pass HUD’s housing quality inspections, and be owned by a landlord willing to accept housing vouchers. This is not easy. Research shows that many landlords resist housing tenants with vouchers (Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Inc., 2012, Cunningham et al., 2018, Phillips, 2017).”

- “Qualitative studies suggest that landlords are wary of housing voucher holders due to some combination of social biases about recipients, low rent ceilings relative to the market, lack of familiarity with the program, and concerns about the administrative hassles of dealing with programmatic rules, perhaps most notably the requirement that homes meet HUD’s housing quality standards, which forces landlords to keep units off the market while waiting for an inspection to be completed and passed (Cunningham et al., 2018, Garboden et al., 2018, Rosen, 2020). Landlords may only believe the benefits of serving voucher holders outweigh the costs for buildings in high-poverty neighborhoods, which cannot attract market tenants able to reliably pay the Fair Market Rent ceilings (FMRs) offered by the housing authority (Garboden et al., 2018, Rosen, 2020).”

- “We expect lease-up rates to vary both across and within markets, according to the difficulty of finding voucher-suitable homes. Across markets, the most obvious predictor of lease-up is the rental vacancy rate. Chyn et al. (2019) find that falling vacancy rates in Chicago were associated with lower lease-up rates. Exploiting cross-sectional variation, Finkel and Buron (2001) and Shroder (2002) report that voucher recipients were significantly less likely to lease-up in markets with lower vacancy rates. Finkel and Buron (2001) report an average lease-up rate of 61 percent in markets with vacancy rates below 2 percent, as compared to 80 percent in markets with vacancy rates above 7 percent. In addition, they find that search times averaged 93 to 94 days in very tight markets, as compared to only 59 days in loose markets.”

- “But other, previously overlooked market factors may matter too. First, older housing stocks may mean lower quality homes and thus higher search costs, as fewer units are able to pass required inspections.”

- “Second, greater dispersion in rents across neighborhoods narrows neighborhood options for voucher recipients, as voucher-affordable units (those with rents not much above the FMR, which is set at the 40th percentile rent of recently leased units in the metro area) are concentrated in fewer neighborhoods. New voucher holders can move into units with rents slightly above the FMR, but they must pay the marginal dollars above the FMR and are not allowed to pay more than 40 percent of their income on rent. Plus, greater rent dispersion may mean fewer voucher-eligible units: in high-rent dispersion markets, the units charging rents above the FMR are far above voucher holders’ reach, while many of the homes with rents below the FMR may be so low quality that they cannot qualify for the voucher program. In markets with less rent dispersion, there should be more decent-quality homes charging rents just above and below the 40th percentile.”

- “Within markets, voucher recipients with more urgent needs (e.g., those currently experiencing homelessness or living in market-rate housing) may benefit more from vouchers and therefore to be more likely to lease up. That said, many of the neediest households may also face greater barriers in using their vouchers. On the cost side, Black and Hispanic households may face more discrimination, have more spatially constrained social networks, and be less apt to take advantage of online searches (Krysan et al., 2018 report that white renters are far more likely to use online resources in housing search than Black and Latino renters.). That said, earlier studies drawing on smaller samples find mixed evidence about race.”

- “Finally, though voucher recipients can technically use their voucher anywhere, the characteristics of the neighborhoods where households live when receiving their voucher may affect both the perceived costs and benefits of using a voucher. On the cost side, in neighborhoods with fewer voucher-eligible homes available, recipients are less likely to be able to lease in place or nearby and may have to search farther afield and for longer (Finkel and Buron, 2001 found that more than one in five voucher recipients leased in place in 2000.). As for benefits, the conditions of a voucher holder’s initial neighborhood (such as high poverty rates or crime levels, or the low quality of local public services) might increase the perceived benefit of a voucher that allows them to move to a new environment.”

- “Chyn et al. (2019) is the one lease-up study to consider the characteristics of voucher recipients’ baseline neighborhoods, and they find that people initially living in higher poverty and higher crime neighborhoods are more likely to lease homes with their vouchers. They also find that lease-up rates are higher for recipients from neighborhoods with more recent voucher recipients and larger Black population shares, patterns they attribute to peer effects and stronger social networks, given that over 90 percent of the voucher holders in their Chicago sample are Black.”

- “We rely on unique, individual-level administrative data on voucher issuances and use. PHAs are required to provide information on voucher recipients to HUD, including every programmatic action for voucher recipients, from their receipt of a search voucher (or a promise of a voucher subsidy if they secure an eligible rental home) until their exit from the program. When a search voucher is issued, we observe the exact date of issuance, a limited set of demographic information about the household head (e.g, race and ethnicity, age, disability status), the ZIP Code of residence at the time of receipt of the search voucher, and a flag indicating whether that household was homeless at that time. Further programmatic actions show if the household leases up, the date they enter the program, and the address where the household successfully uses their voucher. Searches are treated as failed if an expiration is issued, or if no further actions are issued.”

- “We calculate lease-up rates for new voucher recipients for the years 2015 through 2019.4 We calculate both 60-day lease-up rates (HUD requires PHAs to allow voucher recipients at least 60 days to search for a unit) since estimating lease-up outcomes for different search windows (60 and 180 days) helps shed some light on whether longer allowable search times appear to counter market features and other barriers that impede successful lease-up. Over 95 percent of successful searches are completed within 180 days, and the six-month window helps to trim outliers in the early years of our sample.”

- “We use American Community Survey 5-year data from 2015–2019 to capture market conditions and neighborhood composition, using ZIP Code Tabulation Areas, or ZCTAs, to proxy for neighborhoods … We include variables capturing neighborhood racial composition, poverty rates, and housing conditions (i.e., homeownership rate, vacancy rate, and the share of the housing stock built before 1940).”

- “HUD calculates, for every metropolitan ZIP Code, the Small Area FMR (or ZIP Code-level rent subsidy ceiling) that would apply if PHAs choose to use Small Area FMRs (SAFMRs) rather than metropolitan area-wide FMRs. The vast majority of PHAs during our time period (and all PHAs in our sample) used metropolitan area-wide FMRs, but these SAFMRs indicate relative rent levels in each ZIP Code (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2018). We calculate for every ZCTA, the ratio of HUD’s SAFMR to metropolitan area-wide FMR, to capture the relative affordability or ease of finding homes that rent below the metropolitan area FMR in the ZCTA. We also capture the cross-neighborhood dispersion of rents in a metropolitan area by calculating the ratio of 90th percentile ZCTA SAFMR to the 10th percentile ZCTA SAFMR (the 90/10 SAFMR ratio).”

- “Our lease-up sample is made up of search events, which begin with the issuance of a search voucher. We restrict our sample to search events in metropolitan PHAs that record at least 30 search events and meet data quality standards in each of our five sample years.7 At an individual level, we omit searches for which the previous ZIP Code of residence is missing. These restrictions result in a balanced-panel of 433 metropolitan PHAs, covering 408,025 voucher issuances from 2015–2019 … we believe our analysis covers a representative sample of PHAs and voucher recipients. Our search time sample includes 261,397 successful voucher searches from the same PHAs over the same five-year period. Summary statistics for the full set of variables included in the regressions are shown in Table 2.”

- “Over half of the voucher recipients in our sample are Black, and 49% of households are female-headed with children. Voucher recipients also come from more disadvantaged neighborhoods than other households. The average poverty rate in the neighborhoods where recipients live when they receive vouchers is 20%; only one in five people in the U.S. lived in neighborhoods with poverty rates this high in 2015–2019 (Bishaw et al., 2020). The table also shows that voucher recipients start out in ZIP Codes with median rents below the median in their metropolitan area.”

- “To examine how broad market conditions shape search experiences, we estimate linear probability models of lease-up, in which the dependent variable takes on a value of 1 if the household successfully leases a unit with their voucher within either 60 or 180 days of receiving it. Our key independent variables capture market factors, such as the rental vacancy rate, the share of the housing stock built before 1940, the 90/10 SAFMR ratio described above, as well as a set of variables capturing county demographics. We also include a few high-level voucher policy variables: a dummy variable indicating if the county is in a state with a law banning housing discrimination on the basis of voucher use or source-of-income (SOI), and the share of rental units in the county that were financed through the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) since LIHTC owners are mandated to accept vouchers. We hold constant individual household characteristics to control for compositional differences across markets. Specifically, we include variables to capture household composition, age, race/ethnicity, income, disability status, immigrant status, homelessness status and residence in public housing at the time of issuance.”

- “We estimate regressions of search time for the subset of voucher recipients who successfully lease up, using the same independent variables, since theoretically factors affecting lease-up rates should also affect search times.”

- “Our estimates show that 61 percent of voucher recipients were successful in leasing homes with their vouchers during this time period, with annual lease-up rates falling from 63 in 2015 to 60 percent in 2017–2019. This decline is consistent with growing tightness in the rental market during this time period. Median search time for successful searches ranges between 59 and 63 days. We see modest seasonality in the patterns, with average monthly lease up rates ranging from a low of 60.1 percent in August to a high of 61.9 percent in January, and search times ranging from a high of 63 days in November to a low of 54 days in January.”

- “The variation across markets and PHAs is more striking than the variation over time. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of 180-day lease-up rates in 2019 across the 433 PHAs in our sample. Although there is notable clustering around the median, 10 percent of housing authorities saw lease-up rates of 43 percent or less, while 10 percent saw lease-up rates of at least 80 percent. In terms of search times, 10 percent of housing authorities saw median search times of fewer than 31 days while 10 percent saw median search times of 82 days or more.”

- “In general, observed search times are longer and lease-up rates are lower in markets with lower vacancy rates and greater cross-neighborhood dispersion in rents. But allowable search times are set by each PHA and may also vary by market conditions, with PHAs in more challenging markets permitting longer searches to enable more of them to be successful.”

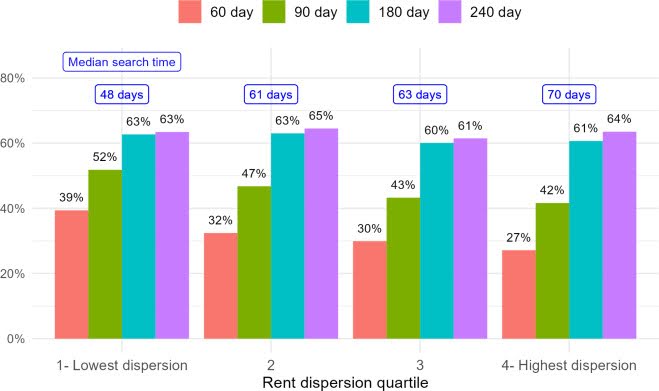

- “We find suggestive evidence of this pattern in Fig. 2, which shows lease-up rates in 2019 within 60, 90, 180 and then 240 days of issuance for PHAs grouped from lowest to highest rent dispersion quartiles. The share of voucher holders successfully leasing homes with their vouchers in 60 or fewer days falls from 39 percent in markets in the lowest rent dispersion quartile to 27 percent in markets in the highest rent dispersion quartile. As we apply longer search windows, lease-up rates increase in all markets, but they increase far more in the high-rent-dispersion markets, leading to a convergence in lease-up rates. Patterns are very similar using quartiles of median rent.”

Figure 2. Lease-up rates by rent dispersion quartile.

- “Table 3 presents results for our regressions of lease-up and search time on broad market factors. The dependent variables are leasing up within 60 days in the first column, leasing up within 180 days in the second, and search time in the third. The coefficients on the market variables generally comport with theoretical expectations. Voucher recipients are more likely to lease up – and in less time – in counties with lower vacancy rates. And other, previously overlooked housing market measures appear to matter too. Consistent with predictions, households are more likely to lease up – and in less time – in counties with newer housing and less rent dispersion. We also see weak evidence that lease-up rates are higher in counties in which a greater share of the rental stock is subsidized through the Low Income Housing Tax Credit and in states that have passed Source of Income Discrimination laws.”

- “In general, broad market conditions appear to matter more in shaping 60-day lease-up rates than 180-day lease-up rates, perhaps because PHA officials endogenously extend search timelines when market conditions are more challenging. Specifically, while higher homeownership rates and newer housing stocks are associated with higher 60-day lease-up rates, we do not see these relationships in the 180-day lease-up regressions. Similarly, the coefficients on vacancy rate and rent dispersion have larger magnitudes in the 60-day lease-up regressions than in the 180-day lease-up regressions.”

- “The coefficient on the share of the county population that is Black flips signs between the 60- and 180-day lease-up regressions, with larger Black populations associated with less successful short searches but more successful long searches. This reflects the longer searches experienced by voucher holders in counties with larger Black populations.”

- “But even after controlling for all these market factors, Black and Hispanic voucher recipients are less likely to lease up with their vouchers. Notably, we see variation across metropolitan areas in the magnitude of racial differences. Table 4 shows that key market factors (other than vacancy rate) appear to matter more for Black and Hispanic households. The regression includes CBSA*year fixed effects and shows that the coefficients on the interactions between cross-neighborhood rent dispersion and Black/Hispanic dummy variables are significant and negative. Black/white disparities in 180-day lease-up rates are 10 percentage points higher in metropolitan areas with the highest rent dispersion than they are in markets with the lowest rent dispersion. Racial disparities in lease-up rates are also significantly larger in counties with older housing stocks, perhaps because Black and Hispanic voucher recipients tend to live in the neighborhoods within metropolitan areas where older homes are concentrated.”

- “Table 5 shows variation in lease-up rates across individual households within markets, or CBSAs, as regressions include CBSA-by-year fixed effects. Consistent with theoretical priors about voucher benefits, households living in public housing and thus already receiving a rent subsidy are less likely to lease up, while those experiencing homelessness are more likely to do so. Older adults are more likely to lease homes, and in less time, perhaps because of lower search costs due to greater landlord acceptance. Black and Hispanic households are less likely to lease up than their white counterparts.”

- “There are again differences across search time frames, which are reflected in search time regressions too. The time patterns generally point in the same direction — households that are more disadvantaged in housing markets (households of color, female-headed families, those with no income, and those experiencing homelessness at the time of voucher receipt) all appear to disproportionately benefit from longer search timelines. Consider that Black households make up just 41 percent of those who lease up within 60 days but 58 percent of those who lease up between 61 and 180 days.”

- “The regressions also include ZIP Code variables, and their coefficients are largely consistent across the three regressions. As expected, households living in neighborhoods with lower vacancy rates and higher rents relative to metropolitan area FMRs when receiving their voucher are less likely to lease up as they will find fewer voucher-suitable units in their neighborhood and will need to search further afield.”

- “Overall, our results raise serious questions about whether housing choice vouchers are reaching the neediest sub-group of voucher recipients. While our results show that older adults and people experiencing homelessness at the time of voucher receipt are more likely to be successful in using their voucher, due perhaps to greater search supports from local organizations, households of color and those originating in communities of color are less successful in their searches.”

- “To understand the mechanisms underlying racial disparities, Table 6 shows how coefficients on race dummies change as we add more variables, starting with a regression with only individual characteristics. The second column shows racial disparities when we include CBSA*year fixed effects. The third column shows how those racial disparities change when we add in ZCTA*year fixed effects. For 60-day lease-up, the Black coefficient falls from 12.3 percentage points when only including individual controls to 8.5 percentage points when adding CBSA*year fixed effects, and 5.4 percentage points when including ZCTA*year fixed effects. In other words, neighborhood conditions explain 36.5 percent of the average, within-metropolitan area Black–white disparity. For 180-day lease-up, the Black–white disparity falls from 4.1 to 2.3 percentage points when adding ZCTA*year fixed effects. We see a similar pattern for Hispanic voucher recipients though disparities are smaller. Roughly 40 percent of the racial and ethnic disparities in other words, may be explained by Black and Hispanic households living in neighborhoods with more challenging market conditions.”

- “To help understand why individual – and neighborhood – race appear so significant in voucher search experiences, we examine racial differences in the prevalence of cross-neighborhood moves to see if Black and Hispanic voucher recipients are more likely to end up in homes that are further from their original communities, suggesting more challenging, or at least less familiar, searches. (Voucher holders who move to new ZIP Codes when renting homes search for 19 days longer on average.) In 2019, 58 percent of all voucher holders moved to a new ZIP Code when leasing up, but the proportion moving to a new ZIP Code ranges from 43 percent for white voucher holders to 68 percent for Black voucher holders.14 This pattern runs counter to evidence from the PSID indicating that Black and Hispanic renters in general are less likely than white renters to move to new neighborhoods when they move to different homes (Krysan et al., 2018).”

- “A comparison of the origin and destination ZIP Codes of voucher holder movers shows that on average they end up in neighborhoods with somewhat lower poverty rates, newer housing stocks, and lower Black population percentages (Table A.5). Note that Black movers experience the largest declines in poverty rate on average (1.7 percentage points) and the largest decline in the share of homes built before 1940 (3.4 percentage points). Differences are not that large though, and this is to some degree expected given that Black voucher recipients start off in ZIP Codes with higher poverty rates and older housing stocks. Voucher holders of all races end up in neighborhoods with lower shares of own-race neighbors.”

- “While our results do not show causal relationships between specific policy interventions and voucher search experiences, they nonetheless offer some suggestive evidence about strategies PHAs could use to both boost lease-up rates and reduce racial disparities in search outcomes. First, the fact that racial gaps are lower for 180-day lease-up rates than for 60-day lease-up rates suggests that extending search times would not only increase overall lease-up rates, but also disproportionately benefit Black and Hispanic voucher recipients. It is possible that this relationship results in part from some PHAs endogenously extending timelines for voucher recipients who they believe face larger barriers. HUD grants housing authorities discretion in who receives extensions, and indeed suggests that they consider household factors that “made finding a unit difficult”.15 HUD might strengthen these recommendations or even mandate longer minimum search times to ensure that disadvantaged households have the time that they need to find voucher-suitable homes, as it did recently for the emergency housing vouchers issued during the pandemic. With careful planning and tracking, longer search times would not mean more unused vouchers, as PHAs can adjust issuance numbers accordingly.”

- “Second, broader enactment and enforcement of source of income discrimination laws could help to boost lease-up rates and reduce racial disparities as well. Table 4 suggests that source of income discrimination laws would disproportionately increase lease-up rates for Black and Hispanic voucher holders.”

- “Our results also suggest that using SAFMRs rather than metropolitan-wide FMRs to set rent subsidies could potentially boost overall lease-up rates, since SAFMRs counteract the rent dispersion and make homes in a broader set of neighborhoods affordable to voucher holders. Further, Table 4 shows a stronger association between Black and Hispanic lease-up rates and rent dispersion, suggesting that moving to SAFMRs would also reduce racial disparities in lease-up.”

- “Finally, and perhaps most importantly, HUD might reconsider modifying housing quality inspection requirements, for instance, by allowing homes that have recently passed municipal inspections to qualify for the program, or by encouraging the use of virtual inspections or tenant-led inspections, guided by quality checklists and supplemented by random audits.”

Shane Phillips 0:04

Hello, this is the UCLA Housing Voice Podcast, and I'm your host, Shane Phillips. This week we're joined by Sarah Strochak to share her research on housing voucher lease up rates, which, as you will hear, are sort of abysmal.

Housing Choice Vouchers are the largest housing subsidy program in the country, yet today only about 60% of people who are issued a voucher actually end up leasing a unit with it. And when recipients fail to find a home to go with their voucher, they have to go to the back of a waitlist that in some places is more than 10 years long. It is a huge issue and one that has been an issue for many years, but it's gotten relatively little attention. To better understand what's going on here, Sarah's team put together data on hundreds of thousands of voucher recipients, easily the largest study on this subject in decades. Their findings shed light on the importance of giving people longer search timelines, especially in higher cost, lower vacancy markets, the benefits of small area fair market rents and source of income discrimination laws, and how lease up outcomes differ by race and ethnicity and by neighborhood characteristics. And we talk about all of that and more in this interview. Just a heads up, this is the first of two consecutive episodes on the Housing Choice Voucher Program.

The Housing Voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies with production support from Claudia Bustamante, Irene Marie Cruise, and Tiffany Lieu.

As always, thanks in advance for sharing the show with your friends and sending your questions and feedback to shanephilips@ucla.edu. With that, let's get to our conversation with Sarah Strochak.

Sarah Strochak is a PhD candidate at NYU Wagner and a doctoral fellow at the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, and she's here to discuss her research on housing choice voucher lease up rates. Why so many people who receive a voucher never find a place to use it and how we might start to fix that problem. Sarah, thanks for joining us and welcome to the Housing Voice Podcast.

Sarah Strochak 2:20

Thank you for having me.

Shane Phillips 2:22

And my co-host today is Mike Lens. Hey, Mike.

Michael Lens 2:24

Hello, Shane. Hello, Sarah. Another Furman Center affiliate for our listening pleasure. You got a name for that, don't you? Sarah is not yet a Foreman-er. I am a Foreman-er. She is a Furman-er.

Shane Phillips 2:38

I don't understand that. As in former. A lot. Oh, okay. That makes more sense. Got it. All right, well, Sarah, we always start each episode by asking our guests for a tour of a place they know, they love, they want to share with our audience, even if you don't love it, but think it'll make for interesting conversation. We want to hear about it. So where are you taking us?

Sarah Strochak 2:58

Okay, well, there's a lot of places that I could choose in New York City where I live and where the Furman Center is based. But I actually wanted to talk about a town in Michigan called St. Joe, Michigan in Southwestern, the Southwestern part of the state right on the lake. And the reason that I think it's so great is that to get there, you can take a train straight from Chicago, you take an Amtrak train directly along the lake into an old train station in St. Joe that has been converted into a pizza place with a beautiful deck with a view of the lake. And I think it's the perfect urbanist getaway where you can take the train right there, stop for a slice of pizza, and then walk into the town.

Michael Lens 3:40

That sounds fantastic. And I bet it's not like that casserole deep dish stuff that they serve in Chicago.

Sarah Strochak 3:47

No, it's Chicago tavern style pizza, which I think is the best type of Chicago style pizza.

Michael Lens 3:53

I'll take that.

Shane Phillips 3:54

Do you have a personal connection to this place or you just personally love it?

Sarah Strochak 3:58

My family goes there.

Shane Phillips 4:00

Yeah, and who can afford to stay in New York City these days anyway, right?

Sarah Strochak 4:03

No, no.

Shane Phillips 4:04

Not somewhere else. Right. I hear traveling there is a little expensive these days. Okay, so today we are talking about a Journal of Housing Economics article from March 2024 titled Race, Space, and Takeup, explaining housing voucher lease up rates. Sarah is co-author on this study, along with former guests, Ingrid Gould-Ellen and Catherine O'Regan. We've talked about housing vouchers before, including with Rob Collinson in episode 17 and Beth Shin in episode 21 slash 64, same episode, but it is a rich subject and this time we're getting into an entirely different aspect of the voucher space, which is lease up rates, or as Sarah will explain, success rates. I'll give some background and then we can get to the questions. Housing Choice Vouchers, formerly and probably still more popularly known as Section 8 vouchers, are a federally funded program administered by local public housing authorities that help people pay rent in the private rental market. Tenants with vouchers pay 30% of their income toward rent and the government covers the remainder up to a maximum amount, and that maximum corresponds to around the 40th percentile rent in the metro area, though our conversation with Rob is all about the biggest exception to that which are small area fair market rents, which I think we will return to. Anyway, despite these vouchers being in quite short supply and hard to get, and actually very generous compared to many American safety net programs, 40% of people who receive a voucher never end up using it. If they can't find a place that will accept their voucher as payment, in some places in as few as 60 days, then it expires, the recipient loses their chance to use it, and they go to the back of a line that might be years or even more than a decade long. Vouchers are the largest rental housing subsidy program in the country, serving millions of households every year, but despite nearly half of recipients being unable to use them, there has not been a whole lot of research on the subject of lease up. Before this study was published, the last national study on lease up rates dates all the way back to 2001, and it only looked at 2600 voucher recipients, so clearly this is a very important issue that deserves more attention, and really has for some time. The study delivers a bunch of interesting results, including finding that the lease up rate fell from around 70% in 2000 to 61% by the late 2010s, that rates are roughly twice as high 180 days after issuing a search voucher as they are at 60 days, that lease up rates are lower and search times are longer in jurisdictions with lower vacancy rates and older housing stocks, and, consistent with many other housing and non-housing topics, that outcomes were consistently worse for Black and Hispanic households, even controlling for neighborhood characteristics and such. So that is a bit of a preview, or maybe a lot of a preview, but before we get into the details of this study with Ingrid and Kathy Serra, something I do really appreciate about this article is that there's almost as much good stuff in the background and theory section as there is in the study itself, and that is not a slight against the study, it's just a very good literature review. This definitely is not a topic I'm personally well versed in, and I learned a ton just reading through that section, so let's just start there. What did prior research on housing vouchers have to say about lease up rates, about disparities in those rates between different groups of people, and the individual neighborhood and market conditions associated with better or worse lease outcomes? Basically, what did we already know going into the 2020s when you started this, and what was still missing from the literature?

Sarah Strochak 7:41

Yeah, research on voucher take-up rates or success rates has been somewhat sparse in the past. So prior to this study, the best measures of voucher lease up rates came from these big HUD-sponsored studies that involved working with just a small selection of the nearly 2,000 local housing authorities that administer vouchers all over the country. So as you mentioned, the last of these studies was published in the year 2001, covering data from the year 2000, and this study covered just 48 housing authorities and showed that, as you mentioned, only around 70% of households were successful in using their vouchers. So up until the point where our study was published, this was the last representative study of success rates or lease up rates, and what they found in the study is that there are some differences in success rates across market conditions or across individual demographics. One of the most striking findings is that success rates are considerably higher in looser housing markets. So in tighter markets, it's more difficult to use vouchers. Success rates tend to be lower and search times tend to be longer. And while the paper found some differences across individual characteristics, for example, elderly households had lower success rates in the study, there actually weren't a ton of differences at the individual level. So they didn't find any big differences across race, ethnicity, or household size.

Shane Phillips 9:06

Is that partly just how few people were in the study? I mean, I think you said 40-something public housing authorities, 2,600 recipients.

Sarah Strochak 9:15

It could be part of it. In this paper, they also focused on larger urban housing authorities. So while these 48 PHAs are representative of that group, it's not necessarily representative of the program as a whole. There's been one other study that's looked at success rates that was published in 2019 that just studied success rates in Chicago between 1997 and 2003 and found that only about half of households who received vouchers were able to use them in that time period. In this study, the authors actually found that success rates were higher for black participants than for white participants, although their sample did consist of about, I think their sample is about 91% black households. So there also could be some differences there. So in the past, our research on success rates has been either for this one housing authority at a time or for a much smaller subset of housing authorities in general. And to my knowledge, there has not been a lot of work on the impacts of the neighborhoods where voucher holders live when they receive their vouchers. So while we've kind of looked across individual and market characteristics, the neighborhood characteristics has been relatively unexplored.

Shane Phillips 10:28

Got it. And yeah, we will come to your data and how you expand on what's been done before. But before we get there, you mentioned in the article how it's kind of surprising that the housing voucher lease-up rate is so low and has been for such a long time. Could you say more about the aspects of the voucher program that make these low lease-up rates or success rates seem surprising at first glance and then share some of the explanations for why maybe we shouldn't be so surprised?

Sarah Strochak 10:56

Yeah, absolutely. So the first thing to understand about voucher take-up rates is that the voucher program is not what we call an entitlement program. So an entitlement program means that any person who is eligible for the program will be able to receive benefits. So you can think of programs like SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as food stamps, or TANF, the Temporary Assistance for a Needy Families Program. So with programs like these, economists and policymakers are often concerned with take-up rates or the share of eligible households who are receiving benefits. And program take-up can be low because households often have to jump through several different hoops to receive benefits, and this is called administrative burden. And this can include things like certifying their income, submitting their application correctly, and attending meetings or briefings. So all of these kind of different steps in the process can influence who actually receives benefits. But vouchers are different in several ways. So first, since vouchers are not an entitlement, many households who are eligible for the program will never receive benefits.

Shane Phillips 12:01

Right. Even if they apply and go through that process.

Sarah Strochak 12:05

Yes. So the program is oversubscribed. Housing authorities across the country have long wait lists, and they don't have the funding to provide vouchers for all households who are income eligible. So this means that households who receive vouchers have already made it through several steps in the process, right? They've successfully gotten onto a wait list. They've waited sometimes for multiple years for a voucher to become available. And then they've confirmed that they're eligible and they're interested and they've been issued a voucher. And still, many households will not be able to complete that final step and secure housing with their voucher. So they'll have to return their voucher back to the housing authority.

Shane Phillips 12:42

And just to underline that point about the wait time, I've been in Los Angeles for around 11 years now. And I believe you can't even add your name to the wait list most of the time. I think during the 11 years I've been here, it's opened maybe twice, maybe three times. Three times, I think. Usually for like a few days or a few weeks and tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of people will add their name and a order of magnitude or more less than that will actually be pulled off of the wait list in the following years. And so I think in Los Angeles, it varies a lot from housing authority or region to region, but in Los Angeles, I think the wait is approaching a decade. And so beyond all the process of actually applying and getting approved and certifying and all the problems you also have with TANF and SNAP and so forth, you also just have to wait an enormously long time, especially in places that have such high demand like Los Angeles and New York and other high cost cities.

Sarah Strochak 13:41

Exactly. It's worth discussing the consequences of returning that voucher. So I mentioned that the program is oversubscribed, but many housing authorities will have their wait list closed and will only open them for short periods of time. So for instance, you mentioned LA, but the New York City Housing Authority opened their wait list last year in 2024, and that was for the first time since 2009. So that means that when a household fails to use their voucher, they might not be able to get back on the wait list to get a second chance. That might mean waiting for years and years for a wait list to even open to apply and be selected and then get back on the list. So returning a voucher to a housing authority has big consequences for these households. So that's the first difference is that vouchers are not entitlements. The second difference is that voucher recipients have to navigate a much higher level administrative burden relative to other programs because they also have to search for housing. So this means that they don't just have to meet all the requirements for the program, but they have to find a home that meets their needs and preferences. And I think anyone who has searched for housing recently knows how difficult this can be. Where I live in New York, we talk about this daily. So voucher recipients have a lot to navigate and they only have a limited amount of time to do so. And the last component of the program that makes it different from other programs is that the voucher program requires landlord participation. So once a household is leased up with their voucher, their benefits or the housing authority's share of their rent are paid directly from the housing authority to the landlord. So unlike other programs where the benefits are going to flow from the government directly to the household, the voucher program requires this extra step of a third party agreeing to participate as well. So on the one hand, low success rates are surprising because households who are issued vouchers have already made it through multiple stages of the program take-up process. And another thing to note is that the voucher program provides a very generous subsidy. So in our study, the average household received around $8,000 per year, which is considerably higher than other anti-poverty programs like SNAP, TANF, or the Earned Income Tax Credit. However, voucher recipients are also dealing with both program take-up and an increasingly difficult private housing market search and this kind of complex third party interaction. So maybe if we think about those factors, low lease up rates shouldn't really surprise us too much.

Shane Phillips 16:06

I hadn't thought about this before, and I'm sure there's some, if not quantitative evidence on this, at least some idea of whether this is a problem or not, but I'm thinking about if you were someone who got onto the wait list in 2009 in New York and you're getting a voucher in 2025, are some of the people who are receiving these search vouchers just like past the point where they want or need these vouchers or they just, for one reason or another, they're getting approval or they're getting the search voucher, but they don't actually necessarily intend to use it? Or when you come off that wait list and actually receive the voucher, is it like you still have to take some affirmative steps where if you get to that point and you actually get the search voucher, then you're clearly still looking for something?

Sarah Strochak 16:55

Yeah. So this is a good question and something that comes up a lot. And the answer is that once a household enters our data set, it means that they've affirmed that they're both interested and eligible for the voucher and that they want to continue in the process. So people aren't going to be issued vouchers if they don't attend a briefing at their housing authority and confirm that they are interested in the voucher. So while I'm sure there are households that are contacted for vouchers who are either ineligible or are no longer interested in receiving the vouchers, those households are not going to be in our sample here.

Shane Phillips 17:27

Okay. So yeah, this is like a 60, 70% success rate among the people who actually move forward and are eligible and everything. Okay. That's good to know. Exactly. So then what should we know about what the search process looks like for tenants once they've received a voucher? Like what boxes do they have to check before the public housing authority, the PHA will start making payments to their landlord?

Sarah Strochak 17:49

So once a household reaches the top of the wait list, they're contacted by their PHA and they'll attend a briefing at their housing authority that details all the steps that the household has to take to search for housing with their voucher and get that housing unit approved to start receiving benefits. So households have to find homes that meet all the program guidelines. First, the rent for the unit has to fall within the program's rent ceilings, which are called payment standards. And we'll talk a little bit more about how those rent ceilings can create challenges for participants once we get into the results. Housing authorities also conduct what are called rent reasonableness checks to make sure that the rent that the landlord is charging is generally in line with similar homes in the area. And then second, the housing authority has to come and inspect a potential home and make sure that the unit passes housing quality standards. And then the last important thing is that the landlord has to agree to participate in the program and house the voucher holder. So what this looks like is that the participant searches for a home. Once they find something suitable, they submit this home to their PHA for inspection and approval. If this all goes well, the household signs a lease with the landlord, the landlord signs a contract with the PHA, and then the household will start receiving their subsidy. So the housing authority will start paying their portion of the rent directly to the landlord. The household generally pays 30% of their income in rent.

Shane Phillips 19:12

And it seems like not finding a landlord to accept a voucher is one of the main reasons that the success rate is not higher. So again, we've talked about this in different episodes, a few where we talked with folks who had done research on kind of the landlord side of things, including Eva Rosen and Philip Garbodin. But what do we know about why landlords so frequently turn down applicants who use a housing voucher or want to use a housing voucher to pay their rent?

Sarah Strochak 19:39

So there's lots of great qualitative and quantitative research that both documents that landlords do sometimes discriminate against voucher holders and also can give us some insight about why landlords may or may not accept vouchers. So some landlords are deterred by the administrative burden of participation, right? They're going to have to keep their housing units up to code, deal with the housing inspections, and then they kind of have to navigate the bureaucracy of the housing authority. So there's administrative burden for the participants, but there's also an added step for landlords that landlords wouldn't have to deal with when renting to an unassisted renter.

Shane Phillips 20:15

I do want to make clear that that's not entirely just like a laziness thing necessarily or wanting to evade stricter rules. I think that inspection process in particular, even if you're confident that you would pass it, sometimes the wait for that inspection can be quite long, right? Like we're talking at least weeks potentially before someone will come out and inspect. And during that time you are not able to charge rent, you're not able to lease up the unit formally. And so you're losing out on income that if you rent it to someone without a voucher, you could start earning more quickly.

Sarah Strochak 20:48

Exactly. Sometimes those inspections can take a while to complete and that can dissuade landlords from participating in the program. However, some landlords are also more motivated to participate in the program when they think that the benefits of participation may outweigh the cost of complying with the program requirements. So in some cases, landlords are going to receive a more stable flow of payments as a portion of the rent is going to be paid directly by the housing authority. So they don't have to worry about the tenant not paying that portion of the rent. So landlords are in some ways disincentivized from participating because they have to deal with this extra administration. But some landlords also choose to participate because they think that the benefits they get from participation are outweighing these compliance costs.

Shane Phillips 21:32

And I feel like we should just say that there are racial implications here. There are class considerations where landlords will often associate Section 8 vouchers. I mean that term Section 8 is a very loaded term at this point and I think is why we tend to really focus on calling them housing choice vouchers is to get away from that. But people will hear Section 8, they'll hear vouchers and think, this is a black household, this is a poor household that is not going to live in the unit responsibly, not going to pay their rent, going to do damage, whatever. And I don't think there's a lot of evidence that those biases are supported, but they are real and they do affect the acceptance of those payments where they're free to discriminate, which in many jurisdictions they are, although that is changing in many places, which we'll get to.

Sarah Strochak 22:21

Exactly. Those types of stereotypes definitely play a role in the decision of some landlords, whether or not they want to house voucher recipients.

Michael Lens 22:28

Does some of it come down to what your alternative is as a landlord? You know, I think there's a fair amount of research that suggests that some landlords like to specialize in these Section 8 or housing voucher market because that's the best option for the particular building or set of buildings or neighborhoods that they operate in versus other neighborhoods or buildings. This is seen as a disadvantageous source of income that is less desirable than their options as a landlord or even in the extreme stereotype is like they think that bringing in this clientele could push away some of their existing clients and tenants.

Sarah Strochak 23:21

Yeah, exactly. And there's great research in this area. Philip Garbot and his co-authors talk to over 100 landlords and they came up with this theory of the counterfactual tenant, right, where landlords are making choices on whether or not they want to participate in the program by considering their tenants that they would have if they did participate versus the tenants that they would have if they did not. So oftentimes, landlords are choosing between a low-income family with a voucher or a low-income family without a voucher. And in that situation, the family with the voucher holder may actually be more attractive to the landlord because they have this, they're able to afford a higher rent and they also have this guaranteed source where part of their rent is coming straight from the housing authority. So in those types of situations, landlords might choose to kind of specialize in voucher holders when they operate mostly in certain neighborhoods where their counterfactual tenants are kind of similarly poor but unassisted households.

Shane Phillips 24:18

Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. So getting into your study, we had this research from a couple decades ago showing that the lease-up rate at that time was around 70%, but rental markets have gotten much tighter in the intervening years and so there was reason to believe that the number had declined. That 2001 study looked at 2,600 voucher recipients enter your project, which looked at over 400,000. Tell us about the data you used for this analysis. Was it not collected before or had the data just not been used for some reason?

Sarah Strochak 24:52

Yeah, so one of the big contributions of this study is the data that we used. So we use administrative data that housing authorities submit to HUD, to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. So while this data has been collected for quite some time, it's never been used before to calculate lease-up rates. So what I mean by administrative data is that these data are created as a byproduct of the operations of the program. So it wasn't specifically collected for research purposes. Housing authorities submit this information on program participations to HUD where it's compiled into a database. So we got access to this data through a research partnership with HUD where the goal was to take a deep dive and develop a methodology to be able to use these data to calculate lease-up rates. And the reason that this data had never been used in the past to measure success rates is that it can be quite complicated. So we parse through millions of observations so that we could create search histories and track outcomes for each household who receives a voucher. And we had to do a lot of due diligence to make sure that this methodology made sense. So we had many conversations with housing authority staff across the country, and we worked really closely with HUD researchers and policy staff who have extensive knowledge about how the program is administered and how that might show up in the data. So this is why we're able to cover a much larger share of the voucher program than past studies because our study doesn't involve any customized data collection efforts. We're just using this data that's already automatically collected and figuring out how to get the most out of it as we can.

Shane Phillips 26:24

That's great. And it also, when you say this is using administrative data that was not generated for research purposes, I just immediately shudder to think at how much of a challenge that must have been to clean and assemble that data because even data that is collected for these purposes is often a challenge to work through and parse. And so I just can't imagine what all these disparate submissions from different public housing authorities look like when you first started with it.

Sarah Strochak 26:51

It is challenging and the voucher program is decentralized. So it's, you know, over 2,000 housing authorities are, you know, some people say there's not really one voucher program. There's many different voucher programs. So housing authorities can make their own decisions sometimes about how they're going to submit data and what that's going to look like. The voucher program is also extremely flexible where voucher recipients can take their vouchers and they can port into other jurisdictions. They can move multiple times in a year, you know, and the program is designed to be flexible, but that same flexibility can make the data really complicated.

Shane Phillips 27:25

Well, speaking of the variation between different housing authorities, there are a lot of results for us to talk about here, but I think the place I'd like to start is the role of search window timeframes on lease up rates or success rates. The lease up rate at 180 days after being issued a search voucher is double the lease up rate at 60 days, 61% versus 31%. Was that at all surprising or has it always been pretty well understood? I learned from your paper that housing authorities get to set their own search window timelines, though it does have to be at least 60 days, and seeing these results left me kind of shocked that you could set timelines so short or that really any public housing authority would choose to set it at that low end threshold of 60 days.

Sarah Strochak 28:13

Yeah, in some ways this is a surprising finding given that the minimum amount of time that housing authorities can give households to search is 60 days. And as we've already spoken about a bit, a lot has to happen in those 60 days. And I can actually tell you a bit more about allowable search time policies as I've been doing some data collection work as part of another project, a related project. And what I found is that most housing authorities do offer a fair bit of flexibility that can explain why such a small share of households succeed within that 60 day mark. So for example, PHAs have wide discretion to offer extensions and the vast majority of housing authorities take advantage of this. Some PHAs will also choose to offer longer than the minimum 60 days. And PHAs also generally pause the clock when households are waiting for their potential homes to undergo their inspections. So even PHAs that do have stricter 60 day time limits may see search times above 60 days because those households are going to have their time suspended while they're waiting for the housing authority to process their units.

Shane Phillips 29:18

I can also see from the perspective of the PHA, a shorter search window with a flexible extension policy might kind of incentivize people to hurry up a little bit and to find something quickly, as long as they are aware that they can get an extension and don't just like give up if they don't find it in 60 days and just walk away from the program, which would be a really bad outcome. But if it does kind of push people to speed up and find something as quickly as possible, that might be the right balance potentially.

Sarah Strochak 29:50

There's definitely a lot more to explore there about which of these policies is best for getting households into vouchers. And one of the most interesting related findings here that has actually motivated a lot of this follow up research is that search times and therefore the difference that we see between those 60 day and 180 day lease up rates vary really widely across the country. So in tighter housing markets, very few households succeed in 60 days or less, whereas in looser housing markets, this is more common. And this can be a reflection of both that it just takes longer to find and secure voucher eligible housing in tight housing markets, but also that PHAs are going to set their search time policies to try and account for this added difficulty.

Shane Phillips 30:34

Right, right. Yeah. So the fact that on average, only 31% of households lease up within 60 days might be masking the fact that in a weaker market with lots of available homes, you might have a 60 or 70% lease up rate within that time. But in Los Angeles or Seattle or New York, it might be under 30% within 60 days.

Sarah Strochak 30:58

Exactly. So that gap between those lease up rates is going to vary a lot across the country. And in fact, Los Angeles has one of the largest gaps in the country because they have extremely long search times. So households can take well over 100 days to use their vouchers in big cities like Los Angeles or New York.

Shane Phillips 31:16

Can you talk about this concept of rent dispersion? What is it? How do you measure it? And what are the reasons we think this might contribute to worse lease up rates or lower success rates?

Sarah Strochak 31:28

Yeah, so we use a measure of rent dispersion to capture how much rents tend to vary within a metro area. And we calculate this measure by taking the ratio of the 90th percentile rent in a metro to the 10th percentile rent. So areas with a high value for this metric have high levels of rent dispersion. And this means that there's a really big difference between the highest rent neighborhoods and the lowest rent neighborhoods in that metro. So places with lower values or values closer to one, they have relatively flat rents across the city. And this matters because traditionally there has been one rent ceiling for an entire metro area. So these rent ceilings for the program are governed by what are called fair market rents, which are calculated at about the 40th percentile of rents for recent movers in an area. So in places with higher rent dispersion, there may be more homes with rents that are substantially higher than the fair market rent and therefore out of reach to voucher recipients. So places with high rent dispersion may make for a more challenging housing surge as units that are voucher affordable can also be more concentrated in certain neighborhoods. So in general, what we find here is that observed search times are longer and lease up rates are lower in markets that have lower vacancy rates, but also greater across neighborhood dispersion and rents. And again, this can be kind of both a cause and a symptom of market conditions, right? So allowable search times are going to be set by each PHA and they also are going to vary by market conditions where PHAs in these more challenging markets that have higher levels of dispersion may permit longer searches so that they can enable more households to be successful.

Shane Phillips 33:11

And can you say a little bit more about the reasons that rent dispersion has this effect? One thing we haven't talked about is the fact that even though vouchers will only pay up to a certain rent or pay the gap between someone's income, 30% of their income and some level of rent, tenants can actually rent in units that cost more than that. They just have to pay for every dollar above the fair market rent. And so I guess I can just explain this one and then I can have you explain the other side of the coin. In this case, if you have a low rent dispersion, the rent at the 45th or 50th percentile might not be much higher than the 40th percentile. And so if, as a tenant, you need to pay a little bit more out of your own pocket to rent in one of those units above the 40th, then it's not such a big deal. If the gap between the 40th and 50th percentile is very large because rent dispersion is very high, then you just may not be able to afford that and maybe the housing under 40% is just not going to work for you for any number of reasons. So that's sort of the above 40th percentile rent issue relating to rent dispersion. What's the issue for the kind of lower cost, lower quality units in high rent dispersion jurisdictions?

Sarah Strochak 34:27

Yeah, so in places where there's really high levels of rent dispersion, there's large differences in rents between the most expensive units and the cheapest units, but there also could be differences in housing quality. And since these units have to pass housing quality inspections for voucher holders to be able to live there, it could mean that those units that are affordable under the program are not going to meet other program requirements regarding housing quality. So that's another way that high rent dispersion could make it more difficult for a voucher recipient to use their voucher in a certain metro area.

Shane Phillips 34:59

So it really just kind of narrows the subset of housing where someone could rent, whether for cost reasons or for quality reasons.

Sarah Strochak 35:07

Exactly. And Darrow's a subset of housing. And it also could mean that those units are particularly concentrated in certain parts of the city, which could make it more difficult for voucher recipients to live there if they're not already living in those areas.

Michael Lens 35:20

I would assume that's certainly the case that, you know, location drives a lot of this dispersion or the geography of rent. If it's very price segregated in a sense, it probably drives a lot of that.

Sarah Strochak 35:35

Exactly. Yeah, we definitely, when we started thinking theoretically about what is driving success rates, we thought a lot about kind of the spatial concentration of units within a city. And that's another component that we were trying to capture with this rent dispersion metric.

Shane Phillips 35:50

So the title of the article is Race, Space, and Takeup. So I think we can talk about race a little bit here. Of the three of us here in this interview, I have by far the weakest foundation in statistical analysis. And I will just be honest and admit that I struggled a bit with interpreting the interaction terms in table four and the relative importance of regression coefficients in different parts of the study. I certainly can gather that Black and Hispanic households have lower voucher lease up rates even after controlling for individual neighborhood and market level characteristics. Help us understand or help me understand exactly how much worse they fared and give us a sense for which of the racial disparity findings you think warrant the most attention.

Sarah Strochak 36:36

Yeah, absolutely. So a very consistent finding in this paper is that across all of our different model specifications with different levels of control variables, Black and Hispanic voucher holders consistently have lower 60 and 180 day success rates. And another really striking finding is that there's very large differences in search times between these groups. So Black households tend to search for much longer than White households. And this means that when PHAs set shorter time windows, they may actually be disproportionately disadvantaging Black or Hispanic households where it tends to take them longer to use their vouchers even when they are successful. And this finding has just been extremely salient across all of the different models that we've run and across all the different projects that we're even doing now. This has been a consistent finding that search times are much longer for Black and Hispanic households and particularly for Black households.

Shane Phillips 37:32

So as I mentioned in the intro, you also found that lower vacancy rates were associated with lower lease up rates and longer search timelines. That makes sense, I think, because it's harder for everyone to find housing when vacancies are low as they are in Los Angeles and most expensive coastal cities. And it's especially difficult, I would guess, for people with vouchers for the reasons we've discussed. We talk plenty about housing supply and affordability on this podcast, so I don't think we need to dwell on this point overall. But you also found that lease up rates were lower in jurisdictions where a larger share of housing was built before 1940. And that struck me as meriting a bit more discussion. At first, when I read that, my assumption was that this was just a proxy for housing production and supply. Basically that if a lot of your housing is pre-1940, then you probably haven't been building much, meaning prices are probably higher, and that's going to disadvantage poorer people and people with vouchers most. That may all be true, but what you were really aiming to measure here was housing quality. Can you talk a little bit more about why housing quality matters for lease up rates? We've talked a little bit about this in rent dispersion, but I think we can talk about it a little more.

Sarah Strochak 38:42

That's a really interesting point on the age of the housing stock and the amount of new housing that gets built, and that absolutely may be playing a role in making it more difficult for voucher holders to get into housing in certain areas. We were aiming to measure housing quality here because a home does have to pass a housing quality inspection in order for a voucher holder to get approved to live there. Older homes typically have more maintenance and quality issues, which can cause failed inspections. So in places where relatively few units can pass these housing quality standards, voucher holders may have more trouble getting their homes approved.

Shane Phillips 39:14

So yeah, that might be in addition to these also being places where the supply is just not kept up with demand in some cases. Another interesting result was the racial disparity in the share of voucher recipients who moved to a new zip code when leasing up. And you mentioned how looking at the origin and destination was a contribution of this analysis. So in 2019, 43% of white voucher holders moved to a new zip code compared to 68% of black voucher holders. And I believe Hispanic households were somewhere in the middle. You point out that this finding is somewhat in conflict with earlier research using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics dataset, which found that black and Hispanic renters are less likely to move to new neighborhoods than white renters. But that research is not limited to renters using vouchers. It's just all renters. In that PSID research, I think the view is that it's bad that more black households don't move to new neighborhoods because they're often coming from places with higher rates of poverty and crime and other disadvantages. And a goal of vouchers, an explicit goal, is to help people move to better neighborhoods. Housing choice. At the same time, it's also bad if black households go to other neighborhoods at higher rates because they simply can't find anyone to rent to them in the area where they currently live, assuming that they want to stay there. So I guess, which is it? Is this a positive result for the wrong or a bad reason? Is it a negative result just flatly? Or is it something else?

Sarah Strochak 40:41

Yeah, so there's a few different things to unpack here. The first thing is that when a household receives their voucher, they can choose to use it in the home where they already live. And this is called leasing in place generally. So unfortunately, we aren't able to observe this in our data. But in the 2001 study on success rates that we discussed earlier, the authors found that about 21% of voucher holders use their voucher in the home where they were already living. So it is a sizable share of voucher holders that use this option.

Shane Phillips 41:09

So when you say you can't observe it, you're only observing that they either went to a new zip code or stayed in the same zip code, but you don't know if it's the same house.

Sarah Strochak 41:16

Exactly. We can only observe their zip code on both sides of their search, basically.

Shane Phillips 41:22

So some of these people who stayed in the same zip code probably or definitely stayed in the same home, but many didn't.

Sarah Strochak 41:27

Yeah, a portion of them did. However, not all homes are always going to be eligible for the program, right? So not all voucher recipients are going to have that option. So for instance, if the rent is higher than the PHA's payment standards, if the home would fail a housing quality inspection, or if, for example, the household was doubled up in the home with other family or, you know, crashing with relatives or something, then they're not going to have that option to lease in place. So back to what we can observe in our data, we can see the zip code of the household before and after they use their voucher. And we find that black households are moving zip codes at much higher rates than white households. So on the surface, this might not necessarily be a bad thing. The voucher program was designed to make it possible for households to move to a broader set of neighborhoods than they could otherwise afford and to run counter to other housing programs like public housing, which tended to be located in higher poverty neighborhoods. However, we can also think about this finding in combination with the fact that black households have to search for much longer when they use their vouchers as evidence that black households are facing higher costs to participate in the voucher program. So even when they are successful in using their vouchers, it's more difficult and they're more likely to have to move neighborhoods in order to use their vouchers.

Michael Lens 42:43

So, Sarah, thinking about how we increase voucher success rates and reduce some of these disparities, longer search timelines seem like an obvious solution, at least in jurisdictions where those timelines or windows are currently rather short. You write that, quote, the time patterns generally point in the same direction. Households that are more disadvantaged in housing markets, including households of color, female-headed families, those with no income and those experiencing homelessness at the time of voucher receipt, all appear to disproportionately benefit from longer search timelines, end of quote. So one issue with longer timelines is that you've got more vouchers floating around at any given time. Could that have any negative unintended consequences? And if so, do you have any thoughts on how to manage those?

Sarah Strochak 43:29