Episode 84: A Review of Rent Control Research with Konstantin Kholodilin

Episode Summary: Rent control is one of the most hotly debated housing policies, and also one of the most researched. Konstantin Kholodilin reviewed over 200 rent control studies, dating back decades and spanning six continents, and he joins us to give an overview of their results.

Abstract: Rent control is a highly debated social policy that has been omnipresent since World War I. Since the 2010s, it is experiencing a true renaissance, for many cities and countries facing chronic housing shortages are desperately looking for solutions, directing their attention to controling housing rents and other restrictive policies. Is rent control useful or does it create more damage than utility? To answer this question, we need to identify the effects of rent control. This study reviews a large empirical literature investigating the impact of rent controls on various socioeconomic and demographic aspects. Rent controls appear to be quite effective in terms of slowing the growth of rents paid for dwellings subject to control. However, this policy also leads to a wide range of adverse effects affecting the whole society.

Show notes:

- Kholodilin, K. A. (2024). Rent control effects through the lens of empirical research: An almost complete review of the literature. Journal of Housing Economics, 101983.

- Konstantin’s massive database of rent control policies across the world: Longitudinal database of rental housing market regulations: 100+ countries over 100+ years.

- Willis, J. W. (1948). State rent-control legislation, 1946-1947. The Yale Law Journal, 57(3), 351-376.

- Kholodilin, K. (2020). Long-term, multicountry perspective on rental market regulations. Housing Policy Debate, 30(6), 994-1015.

- “Rent control, like any other governmental policy, has its intended and unintended effects. Its intended effect is to ensure affordable housing, meaning that tenants face a reasonable rental burden. Typically, the rental burden — defined as the share of the rental costs in the total income of the household — is considered reasonable if it does not exceed 30 %.1 The exact threshold and the definition of rental expenditure and income may be a matter of discussion (Ballesteros et al., 2022), but the fact is that a too high rental burden can have devastating effects.”

- “While rent control appears to alleviate the situation of tenants living in the regulated dwellings, multiple other effects emerge. Rent control leads to the redistribution of income. Apart from an evident and sometimes intended effect of reducing the revenues of landlords, it can also lead to rent increases for dwellings that are not subject to control. Thus, tenants living in such dwellings pay more, which reduces their welfare. However, even tenants in the controlled dwellings can suffer from rent control, as maintenance of such dwellings can be reduced, leading to a decreased housing quality. Rent control can also negatively affect the overall supply of housing or, in particular, the supply of rental housing, which can adversely affect many market participants: both tenants and homeowners. Other effects, for example, higher homeownership rates or lower inequality, cannot be treated as positive or negative from a normative perspective.”

- “The decision to introduce rent control and its design must rest upon an objective and comprehensive cost-benefit analysis. Only when the net benefit is positive is the policy sensible; otherwise, it produces more damage than utility. Such cost-benefit analysis can draw upon the rich literature that investigates potential effects of rent control using a robust scientific methodology and reliable data. Here, I provide a comprehensive overview of this literature.2 My objective is to summarize the evidence on the effects of rent control accumulated over the years. Although this study is far from delivering a complete picture of the net effects of rent control, it can still provide useful guidance for making decisions regarding the introduction or reformation of rent control.”

- “Overall, I could find 206 works on the effects of rent control, among them 112 empirical published studies. The latter are the main focus of this study. A list of all these studies is contained in Table 2 in Appendix. This is perhaps the most comprehensive review of the rent control literature encompassing the period between 1967 and 2023.”

- “Rent control involves the government setting a specific price level for rents, usually below the equilibrium price. The theory of rent control usually expects rent control to give rise to three main groups of effects (Arnott 1995). First, those who are able to occupy rent-controlled housing benefit from this arrangement. Typically, these are long-term residents of the area, and their gain comes at the expense of new residents. The latter group often ends up living in more expensive uncontrolled housing or lower-quality regulated rental units.”

- “Second, landlords are compelled to lower their rental prices, leading to a decrease in the value of their properties. In response, landlords might take various actions, such as reducing maintenance spending, attempting to convert their rental properties into owner-occupied homes, and constructing fewer new rental housing units.”

- “Third, the artificially low rental prices create an excess demand for housing, resulting in a range of outcomes. For instance, there can be a mismatch between available housing units and the number of households seeking housing. This mismatch can lead to situations where, for instance, an elderly widow remains in a large rent-controlled apartment long after her family has moved out, while larger households are desperately looking for homes of an appropriate size. In addition, reduced housing mobility stemming from rent control can lead to decreased labor mobility. Discrimination can also intensify, as marginalized groups find themselves disproportionately affected by the housing shortage. Furthermore, black-market activities like the practice of demanding “key money” (a nonrefundable deposit upon moving in) tend to emerge in response to these market distortions.”

- “Two key inquiries arise concerning the impacts of rent control. First, does the array of potential effects put forth by the theory encompass all the possible outcomes, or have researchers identified additional effects not accounted for in the theoretical framework? Second, do the hypotheses formulated by theorists find confirmation in empirical studies?”

Theoretical effects of rent control

- “The number of effects considered by scholars is quite impressive. The literature identifies 26 housing market, socioeconomic, and demographic effects of rent control. When ordered by the number of studies and, thus, by their prominence from the perspective of researchers, the first five effects are controlled rents, mobility, homeownership, construction, and housing quality.”

- “Rent control is aimed at limiting rent increases and, thus, is expected to affect the prices of housing. Rental housing legislation often splits the private rental sector into two parts: those subject (controlled dwellings) and those not subject to rent control (uncontrolled dwellings). The latter are typically newly built or luxury dwellings. Sometimes, rent control is only applied in tight housing markets. For example, the German Mietpreisbremse, or rental brake, introduced in 2015, is valid only in communities where the housing shortage is particularly acute. Rent control can also be applied only to a specific type of landlord.”

- “In addition to its impact on rental prices, rent control can also influence the market selling price — the value — of real estate properties. This is due to the fact that property value is calculated as the sum of expected future rent earnings, discounted over time. Any factor that reduces the expected rental income of a dwelling inevitably leads to a decrease in its value.”

- “As a rule, in the empirical literature, supply refers to the existing rental housing stock. The reduction of supply can imply its physical disappearance through demolition, merger of smaller dwellings into bigger ones, conversion of residential premises to non-residential uses, and conversion of rental dwellings into the owner-occupied ones.”

- “The actual availability of the housing depends not only on the size of the housing stock but also on the proportion of empty dwellings, as measured by the vacancy rate. A tight housing market is characterized by a low vacancy rate implying that newcomers or people wishing to move within the market experience difficulties in finding an appropriate dwelling. Rent control can lead to lower vacancy rates by reducing the incentives to move of the sitting tenants.”

- “The supply effects are related to construction effects, but should not be confused with each other: while the former deal with the stock of dwellings, the latter deal with the flow. The notion of construction in the literature can cover both the total residential construction and the construction of rental dwellings in particular. Unfortunately, it is not always clear from the studies whether they mean the total construction or just rental part of it. Moreover, at the moment of completing dwellings, it is not always clear how they are going to be used: sold to the homeowners or leased to tenants.”

- “A heightened homeownership rate implies that a relatively small fraction of dwellings remains available for rental purposes. A marginalization of the private rental sector could have adverse implications for both the economy and society, given its capacity to provide greater residential flexibility. Unlike homeownership, renting does not demand substantial financial commitment, making it especially advantageous for newcomers, particularly young families.”

- “Another crucial aspect of housing is its quality, which refers to the physical condition and equipment of rental dwellings, encompassing their level of upkeep and the amenities they offer. As indicated by the theoretical framework, rent control has the potential to influence landlords’ motivation to properly maintain their properties.”

- “Misallocation implies that, by distorting price signals, rent control can lead to a mismatch between the supply of, and demand for, rental housing. Thus, sitting tenants in controlled dwellings may have fewer incentives to leave, since they are well protected and have cheap dwellings, often in a good location. Even if the family situation of these people changes (for example, their adult children leave the nest), these people do not change their dwellings, whereas young families, who need such spacious dwellings, are struggling to find appropriate dwellings. Furthermore, misallocation can pertain to an “unfair” redistribution of resources. Despite the intention of rent control to assist low-income households, the actual outcome can be more advantageous for individuals with higher incomes. This stems from the policy’s concentration on regulating dwellings rather than the occupants’ income levels.”

- “The related notion of inequality refers to rent control exaggerating or reducing already existing economic inequality between social classes and ethnic groups. In situations of misallocation, rent control has the potential to exacerbate inequality by disproportionately favoring more affluent households. Nevertheless, considering that lower-income households are more likely to be tenants, whereas higher-income households tend to be homeowners and landlords, rent control might actually contribute to reducing inequality.”

- “Rent control can also affect the socio-economic and ethnic composition of communities … From a theoretical standpoint, rent control possesses the potential to both heighten and mitigate segregation. On the one hand, by generating a surplus of demand in comparison to supply, rent control can lead to dwellings being assigned based on landlord preferences, which might inadvertently foster segregation. On the other hand, by reducing rental burden, rent control can enable lower-income households to reside in more attractive neighborhoods, thereby lessening social segregation.”

- “The theory of rent control implies that it can reduce residential mobility, which measures how long tenant households stay in the same place: the longer this time, the lower the mobility. Under rent control, people occupying dwellings with low fixed rents have fewer incentives to leave. This can have some negative labor-market implications.”

- “The effect on homelessness means that rent control could possibly lead to either fewer or more people living on the streets. On the one hand, rent control could theoretically reduce the rental burden of the lower-income households and, thus, reduce the probability of landlords evicting their tenants of controlled dwellings for non-payment of rent.3 It will not extend its protection to the fragile households living in uncontrolled dwellings, though. On the other hand, the reduction in the supply of rental dwellings due to rent control can result in some people having a tough time when looking for an available dwelling and, hence, increase homelessness.”

- “Net welfare denotes the difference between benefits and costs of rent control. Typically, in the literature, the benefits include lower rental burden for tenants in regulated dwellings, while costs comprise an increased rental burden for tenants in unregulated dwellings and decreased revenues for landlords. Sometimes, dead-weight losses that arise due to higher search costs borne by tenants are also considered.”

- “Tax base effects describe changes in tax revenues caused by the implementation of rent control. This impact can materialize through two primary mechanisms. First, the imposition of rent limits diminishes landlords’ earnings, thus, reducing the state’s taxation revenue derived from their profits. Second, rent control has the potential to diminish the value of properties under its regulation, consequently leading to a reduction in the revenue obtained from property taxes.”

- “Rent control can possibly affect inflation. Indeed, rent index is the largest component of the consumer price index. Therefore, by imposing caps on rent increases the government could decelerate overall price growth.”

- “The literature also investigates the impact of rent control on evictions of tenants by the landlords. It is assumed that, in the absence of protection from eviction, the landlords are more likely to evict tenants. By doing so they are able to set higher rents for the new tenants.”

- “Commuting times denote the time individuals require to journey to their workplace and return home. These periods can extend due to decreased residential mobility: individuals often opt to remain in their existing regulated residences rather than relocating nearer to their workplaces, leading to increased commuting time from their homes to their jobs. The marriage effect refers to the potential impact of rent control on the demographic decisions made by the people. For instance, a lack of rental housing can cause young people to postpone their marriage, since many cultures often require them to live separately from their parents. Finally, side payments represent various unofficial payments, such as key money, that can be fostered by the introduction of rent control.”

Empirical effects of rent control

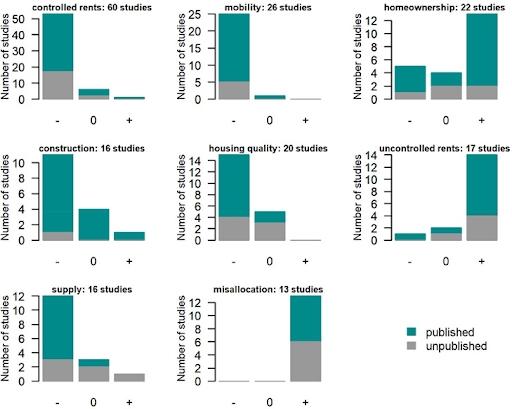

- “Apart from identifying the potential effects of rent control and how much research attention it attracts, it is of critical to analyze the direction of these effects. Indeed, for policy-making it is more relevant to know whether most researchers agree that rent control affects, for example, rents or whether unanimity regarding this effect is lacking. Fig. 2 depicts those rent control effects that occupy the most prominent places in the literature. I select an effect if more than 6 published studies are devoted to it. The left (right) bar shows the number of studies that found a negative (positive) effect of rent control on the corresponding variable. The height of the bar in the middle corresponds to the number of studies that did not find a statistically significant effect of rent control on the variable. For the sake of completeness, along with the number of published studies (greenish shading) I also show the number of unpublished studies (gray shading).”

- Fig. 2. Direction of the most prominent effects of rent control.

-

- “The most prominent effect of rent control is, unsurprisingly, its impact on controlled rents; that is, on rents paid by the tenants of those dwellings subject to rent control. The picture is rather unambiguous: 36 out of 41 published studies (53 out of 60 published and unpublished studies) point to a statistically significant negative effect. Thus, rent control is quite effective in capping rents … half of these consider first-generation rent controls, while the remainder analyze second-generation rent controls. Thus, no big differences are observed in terms of methods, data, and policy design between these studies and those that find negative effects.”

- “By contrast, according to the studies examined here, as a rule, rent control leads to higher rents for uncontrolled dwellings. The imposition of rent ceilings amplifies the shortage of housing. Therefore, the waiting queues become longer and would-be tenants must spend more time looking for a dwelling. If they are impatient or have no place to stay (e.g., in the houses of their friends or relatives) while looking for their own dwelling, they turn to the segment that is not subject to regulations. The demand for unregulated housing increases and so do the rents. Only one published study — Bonneval et al. (2021) — finds no statistically significant of rent control on uncontrolled rents.”

- “The estimated effects of rent control on rental prices exhibit considerable variation across diverse studies. For controlled rents the range is between -57 % and -1 %, whereas for uncontrolled rents it is between -2 % and 14.8 %. The reason for such a variation lies in the different research setups. Certain studies focus on immediate, short-term effects, while others delve into the cumulative, long-term consequences of rent control measures. The average effect of rent control on controlled rents is -9.4 %, while that on uncontrolled rents is 4.8 %. Unfortunately, only based on these results it is virtually impossible to evaluate the overall effect of rent control on housing rents. To do this, a careful analysis of the distribution of housing units across the controlled and uncontrolled sectors is needed. This distribution will depend on a number of factors, including the design of rent control policy.”

- “The impact on residential mobility appears to be quite clear: nearly all studies indicate a negative effect of rent control on mobility. Two potential reasons for this phenomenon are put forward. Initially, residents living in controlled dwellings have limited motivation to relocate. They possess concerns that finding a residence of similar quality at such a low rental cost might be challenging … Secondly, diminished residential mobility could be attributed to heightened tenure stability. Through rent regulation, this policy alleviates the financial strain of tenant households, consequently reducing the likelihood of eviction. Additionally, rent control legislation is often adopted simultaneously with rules protecting tenants from arbitrary removals. As a result, tenants remain in their residences for longer time, thereby boosting their satisfaction. None of these studies find positive effects; only two studies find statistically insignificant effects.”

- “Likewise, the influence of rent control on new residential construction and supply seems to be similar. Approximately two-thirds of the studies indicate a negative impact, while several studies discover no statistically significant effect whatsoever. Two potential reasons underlie this variability. Firstly, variations in the design of rent control policies can matter. For example, newly constructed housing could be exempted from control, thus remaining unaffected by rent control regulations. Secondly, the choice of the dependent variable can also affect results of the analysis. Rent control can influence the construction of rental dwellings while leaving owner-occupied properties untouched; in fact, the quantity of owner-occupied dwellings might even increase, thereby compensating for any decline in the number of completed rental units.”

- “The published studies are almost unanimous with respect to the impact of rent control on the quality of housing. All studies, except for Gilderbloom (1986) and Gilderbloom and Markham (1996), indicate that rent control leads to a deterioration in the quality of those dwellings subject to regulations. The landlords, whose revenues are eroded by rent control, have reduced incentives to invest in maintenance and refurbishment, thus they let their properties wear out until the real value of the dwellings decreases and becomes equal to the low real rent. According to Gilderbloom (1986) and Gilderbloom and Markham (1996), moderate rent control does not impact housing quality.”

- “In the case of homeownership effects, the picture is a bit less clear cut: there are multiple studies pointing in different directions. In particular, the relationship appears to be blurred when only unpublished studies are considered. Nevertheless, the majority of studies predict an increase in the homeownership rate due to rent control. This can be explained by the desire of landlords to get rid of those properties that bring them insufficient rental revenues. Therefore, the landlords sell their dwellings or convert them into condominium ownership. By contrast, Gyourko and Linneman (1989), Lauridsen et al. (2009), and Bourassa and Hoesli (2010) find a negative effect of rent control on homeownership, explaining it from the perspective of tenants in controlled dwellings: they are less inclined to become owners, given their protected position.”

- “In this study, I examine a wide range of empirical studies on rent control published in referred journals between 1967 and 2023. I conclude that, although rent control appears to be very effective in achieving lower rents for families in controlled units, its primary goal, it also results in a number of undesired effects, including, among others, higher rents for uncontrolled units, lower mobility and reduced residential construction. These unintended effects counteract the desired effect, thus, diminishing the net benefit of rent control. Therefore, the overall impact of rent control policy on the welfare of society is not clear.”

- “Moreover, the analysis is further complicated by the fact that rent control is not adopted in a vacuum. Simultaneously, other housing policies — such as the protection of tenants from eviction, housing rationing, housing allowances, and stimulation of residential construction (Kholodilin 2017; Kholodilin 2020; Kholodilin et al., 2021) — are implemented. Further, banking, climate, and fiscal policies can also affect the results of rent control regulations.”

Shane Phillips 0:05

Hello, this is the UCLA housing voice podcast, and I'm your host. Shane Phillips, this week, we're joined by Konstantin Kholodilin to share findings from a wide ranging review of over 200 rent control studies spanning six continents and many decades, rent control can be a challenging topic to cover, because it has so many consequences beyond its intended purpose of lowering rents or slowing their growth. Some of those consequences are good and some are bad. Most are unintended, and individual studies tend to focus on just one or two of them at a time. But if your goal is understanding whether rent control is worth it, all things considered, you ideally want to take a wider view. And Constantine's review of the literature offers exactly that rent control also might be the policy I hear the most visceral responses to both for and against and most often without much understanding of its history or how it's typically implemented. I don't ever expect conversations like this to completely change anyone's mind, but whether you count yourself for or against rent control, I hope this overview complicates your views on it. Really, that's all an academic institution could ever ask for the housing voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional policy studies with production support from Claudia Bustamante, Irene Marie Cruise and Tiffany Liu. If you appreciate the show, be sure to tell your friends and colleagues about us and send your questions and feedback to Shane phillips@ucla.edu. With that, let's get to our conversation with Konstantin.

Konstantin Kholodilin obtained his PhD in Barcelona and is a doctor habilitatus and senior researcher at DIW Berlin, and he is here to talk with us about rent control, the many, many empirical studies that have been done on it over the decades, and what those studies have tended to find. Konstantin, thanks for joining us, and welcome to the housing voice podcast.

Konstantin Kholodilin 2:15

Thank you, Shane, I'm happy to talk with you

Shane Phillips 2:17

and Mike is my co host. Hey, Mike.

Mike Manville 2:19

Hey. Good to be with her. Both you guys.

Shane Phillips 2:21

So usually we start with a question about a tour. But Konstantin, I'm actually first going to ask you about the Dr habilitis. What does that mean?

Konstantin Kholodilin 2:31

Well, if I understand it correctly, it seems to be something peculiar for Central Europe, where starting probably from 19th century, but I'm not sure there were two degrees, the first one candidate degree and the second doctoral degree. And this, Dr chabili tatus is actually a doctoral degree that enables you to become a professor. In Germany, they used to have it, and in the past, it had a major importance, but nowadays it's just a kind of ceremonial title.

Shane Phillips 3:00

Well, this is news to me. I've learned something new today. Okay, well, now we can get to our tour. So I didn't ask you about this beforehand, but where would you like to lead our audience around and tell us a few things about.

Konstantin Kholodilin 3:10

Well, I would love to lead you on a virtual tour to my hometown, to St Petersburg in Russia. And I haven't been, unfortunately, there for almost five years. So that's one reason more to go there, at least virtually. And I'd like to talk about three things. The first thing is the beauty of this city. The second thing is somewhat related to urbanism, namely, height restrictions. And the third thing is something very specific to St Petersburg and probably Moscow too, is common. Alkas as a tour guide, I would like to praise the beauty of this city, both natural beauty because it has dozens of islands. It has a very white river, it has sea and it has white nights, so starting from May till mid July, we almost don't have nights there, so you can read book during the night. And it also has architectural beauty, because almost from the very beginning, it was conceived as a capital of a huge empire. So the authorities, the Tsars, or empires, they invested a lot of money in improvement of this city. And so a kind of ensemble emerged. So it's a kind of combination of natural beauty and architectural beauty that makes this it's very special. So you have palaces, you have parks, you have bridges. Some of the bridges open in the middle of the night to let big ships go into, down and up the stream. And if it's in the White Night period, then it's especially nice. And since we started to talk about architecture, one of the things that was adopted in St Petersburg, it was the height restriction. So the highest building had to be the, no surprise, the Winter Palace, which was the residence of the emperors. No other building could exceed that one. And so over the centuries, it shaped the center of the city. So in the center of the city, you don't have high rise buildings. So probably the the highest is 40 or 60 Well, if it's a cathedral, it can be a bit higher. But if it's some multi family house, then it can be higher than 40 or 50 meters. While on the periphery you have very high rise buildings. So in the last 30 years, they built the houses with 30 or 35 stories. So it's something like upside down Bell. So if you compare it to typical American city, then it's just the opposite, because in in a typical American city have very high rise buildings in the center and then very low rise buildings on the country. In St Petersburg is just other way around. So the last thing I'd like to mention in its, as I said, very specific to St Petersburg, is common alkas, singular commonalca, or communal apartment, communal in the sense that in the late 1910s many apartments in the city center were nationalized. And so imagine a five rooms apartment, which used to be occupied by one family. From then on, it was occupied by several families. In the extreme case, five families. So one room, one family, they shared bathroom, they shared kitchen and the corridor. And the interesting thing is that there are hundreds of 1000s of such dwellings. Many of them exist in the 90s, most of them were privatized. But they were privatized also in a peculiar way, because the people were allowed to privatize the rooms where I lived, so not even apartments. This is a very extreme form of home ownership. Its its room ownership. So you could be owner of a room in an apartment shared with other people. And that's one thing I never, never faced, never encountered in other countries.

Shane Phillips 6:59

Yeah, kind of reminds me of, like the tenancy in common, or this kind of thing where you, you sort of have a share in a building, but, but it's also sort of like a condo where it is, you probably just own the the unit itself and everything else is, kind of is sort of shared. That's a very, I don't know how you would who owns the the hallway, the kitchen, the bathroom. Is that each person, it's like, owned in common between the people who own the room, or each room in the in the single unit.

Konstantin Kholodilin 7:25

Exactly. It's a condominium with a fractalization of condo ownership. Yeah, exactly. So it's adapt. So when, when you start with House ownership, then you go to condominium, which actually is not very old thing, because in many European and American countries. The the apartment home ownership originated in the 50s, 60s, 70s. It's pretty young phenomenon, and here we have an extreme form and another poll of the range of the spectrum.

Shane Phillips 7:57

Yeah, that's super interesting. Okay, so our conversation today is about an article written by Constantine and published in the Journal of housing economics earlier this year with the following title, rent control effects through the lens of empirical research and almost complete review of the literature. I think that title says just about all you need to know, but I will say just a little bit more before turning it over to our guest. First is just to note the breadth of this review, which started with identifying 206 different studies on rent control, of which 112 were published, empirical studies going back all the way to 1967 and covering every continent except Antarctica. He identified and categorized 26 different kinds of effects investigated in these studies, ranging from the most common topics like the effects on controlled and uncontrolled rents to less commonly investigated things like its effects on eviction, tax revenues and even marriage rates. The article does a great job, I think, of presenting the theory behind how rent control effects, rents and mobility and housing supply and all the rest, including why it might be expected to have a positive or negative effect on each, or sometimes positive effects for one reason, and negative effects for another, that balance out to some extent. And then it presents in a straightforward way what the empirical studies have actually found, including a great figure that summarizes it all very clearly, and although it is probably difficult to walk away from this literature review feeling like rent control is definitely a great policy where the benefits always outweigh the costs, I appreciate that it offers a lot of nuance and arguments on both sides of this debate or conversation, and ultimately leaves it to the reader to decide where they land on it. So I guess you could say I am a fan. To get us started, Constantine, most of our listeners probably have an idea of what rent control is, and some will even have a version of it where they live, including us here in Los Angeles, which has its own version, and the state of California has a kind of lighter touch version that covers the higher state. But for those of us who don't know as much about this or may have some misconceptions, let's just make sure we're all on the same page. What is rent control? What are its intended outcomes, and how does it try to accomplish them?

Konstantin Kholodilin 10:13

Well, the rent control is a specific case of price control. So you can control housing rents, you can control prices for bread. You can control prices for fuel in this particular case, the intended goal is to either freeze housing rents so prohibit them from growing, or to cap the rent increases. And the idea here is to improve the affordability. Typically, we measure the affordability of housing by rental burden, which is a ratio between the rental costs and households disposable income. So when the share of rental costs in the income is very high, say above 30% then you have you're in trouble. Anyway. You have to pay for your housing. You can cut your food costs, you can cut your cloth costs, you can cut probably your transportation costs, although it's not always possible, but you cannot really cut on your housing cost.

Shane Phillips 11:11

Just to be clear there, you just mean, because you can't, you know, rent out one room in your home for a month or something. There's no it's just a single rent, and there's no downsizing in the near term. Whereas you can maybe make fewer trips, you can you can buy a little less food or cheaper food, but you can't say this month I'm going to consume less housing and only pay 80% of the rent.

Konstantin Kholodilin 11:33

Yeah, sure you the rent is fixed. In case of rent control, is fixed from from above. In case of no rent control, it it's fixed from below. Even if you consume just one room in your apartment, in your dwelling, in your house, you still have to pay for the for the entire apartment.

Mike Manville 11:50

It's hard to consume marginally less housing to save some money the way you can. As Shane said, I'm gonna buy from the bottom shelf of the supermarket for a month, or I'm gonna, you know, like a college student, not do my laundry for a month, right? It's just you can't do that with your rent. It's sort of a close to an indivisibility

Konstantin Kholodilin 12:09

If you control the rent, if you control the numerator of this rental burden, then then you can increase the affordability. Because if the income doesn't change, increases, then the whole thing is declining. So you say from 40% rental burden, you can go down to 30% or even 20% in just one example, for instance, in socialist countries, like in Soviet Russia, in Socialist Germany, German Democratic Republic, they used to control rents all the way from 1930s till 1990 and by the end the this rental burden was just five sometimes even 2% Wow. So that's the effect of freezing rents for 40 kids, for example.

Shane Phillips 12:57

Okay, so that's actually a great transition to talking a little bit about the history of rent control and Constantine. I know you know the history going back a very long way. So maybe we can start with the pre history as it were, and maybe you bring us up to in just a short time, the 1940s roughly. And Mike can pick up there for the history in the US since that time.

Konstantin Kholodilin 13:23

Yes, sure. It turns out that rent control is older than many of us believe. In fact, one of the first documented cases dates back to 4950, before Christ. So it was the times of Julius Caesar, and at that time, the Well, at that time, he wasn't temporary yet, but at that time, rents were frozen. And actually the housing market in ancient Rome was very similar to housing market in Los Angeles or New York City, because it was composed of big multi family houses where rooms were rented. And you can imagine that rental burden was pretty high at that time. There are no estimates, but probably it was pretty high in several cases, the Emperors introduced rent control. They froze rents at the very low level for a year or so. We also find examples of rent control in Song Dynasty, China in 12th century. We find further examples in Europe, like in Madrid in 16th century, and it was related to the move of capital from viadoli to Madrid. So at that time, Madrid was pretty insignificant town, and then all of a sudden, its population crippled and quadrupled, leading to excess demand and to rising rents and to the government introducing rent control, we find plenty of examples of rent control related to founding of a university. So in the Middle Ages, starting from 12th century, many universities were founded in Europe, and in many cases, a committee was created, formed by. By the representatives of the university and of the city that had to set fair rents, so the rents to be paid by tenants and by professors. You have also many other episodes of rent control, for example, protection of Jews in Jewish ghettos, so Jews had no right to be homeowners, so they, they only could be tenants, and they, in most cases, they had to live in specific places called Get us. And in these places, rents were frozen. And actually they remained frozen for a pretty long time, until more or less 8/19 century. Mid 19th century, by the way, in Madrid, in the case I mentioned, rent control existed from approximately 1565, to 8042, so almost 300 years. Yeah, you can imagine how long this longer than we've had a country. Yeah. And then we come actually to the 20th century, because before 20th century, we have specific cities subject to rent control, in some cases, specific neighborhoods, specific population groups. And it's only in 20th century that there was a true exposure of the number of countries that introduced rent control, and it became a mass phenomenon. So it covered entire cities. Millions of tenants were protected by rent control, and it became a very large scale phenomenon. If we want to say a few words about the US, I should probably break one of your illusions, if I may say so, because we find the evidence of rent control in the US already in 1919, so in the District of Columbia, rent control was introduced, and then later on, in either 1919 or in 1920 rent control was introduced also in New York City. There's a nice book on it by Professor Fogel, but it was typically confined to specific cities, so Washington or New York City, and the true nationwide rent control was introduced only during World War Two.

Shane Phillips 17:04

Yeah. And what I'm hearing is, it sounds like a lot of these cases are times when there was a sudden influx of a lot of people, a lot of demand, you know, the capital moves, the university opens, even these new countries forming, there's probably lots of urbanization occurring as a result, or just, you know, because of the the time of technology shifts and everything happening. So I'm sure there's, there's more to say about that, including during wartime and in the post war period, but I'll hand it over to Mike in a second. But you did you have something else to add there? Konstantin

Konstantin Kholodilin 17:36

Yeah, I just wanted to add that. In the case of New York City in 1920 it was not an influx of people. Well, there might be some influx related to workers coming to the to the defense industry enterprises, but interestingly, it was the lack of construction. So for four years during whole World War One, there was no construction in New York City, and it was enough to create housing shortage.

Shane Phillips 18:03

Yeah, Mike, you want to pick it up from there.

Mike Manville 18:06

Yeah. I think, you know, as Constantine points out, you know, you had some starts and stops before World War Two, and then the entry into World War Two led to the US is only experiment with, just essentially nationwide rent control that was actually run by the federal government, and this was a product of a combination of factors, similar to 1917 to 1920 in New York during the Great Depression, very little construction happened in the United States, and then suddenly, with the entry into war, the economy roars to life. There's a huge risk of inflation, and there's a massive internal migration, because people who previously had been out of work are now seeing that they can or, in the case of people who've been drafted, they're being forced to move toward these designated war production centers, which are start off just being a series of large cities on the coast, but then eventually become, you know, spread All over the country as the war effort ramps up, and there is, of course, no way at that time to ramp up construction, because the government has nationalized most industry, and so wood and nails and labor and so forth are under the control the national government severely rationed. And so as a part of that, I think people sort of forget this. You know, it's a long time ago, and it seems so foreign to us, but the US placed price controls on virtually everything. It had a gigantic office under the executive called the Office of Price Administration. It was run by men who later became a very well known economist, John Kenneth Galbraith. And as part of that, they put in place rent controls. And this they went county by county with it, and its County was selected to have a rent control. The government would come in, it would roll back the rents to a particular pre war date and then just freeze them. And these account these applied to all rental housing. It applied to any there wasn't much new construction that was going to happen anyways, but if new construction did happen, it was rent controlled. It happened regardless of turnover. And so these are what we sort of classically call hard rent controls, or perhaps a little bit inaccurately, given that this goes back to, you know, pre Jesus times, first generation rent controls in the US, and they were very comprehensive. But they didn't last very long. Yeah, by 1949 Congress had allowed individual cities to get rid of the rent controls they had, if they so chose. And all of them, except New York did, and even New York ended up adopting kind of a hybrid version. And then rent control was sort of dormant in most of the country until the late 1960s and early 1970s when you started to see again, a large amount of inflation, construction slowing down, a little bit more experimentation, again on the national side, with price controls. Richard Nixon famously froze rents and stuff for a while, and that momentum was picked up by tenant activists in a handful of US cities who passed a series of rent control laws. And because they were local, they all differed from each other a little bit, but most of them became, or were at that time what we call the soft rent controls, where you had the vacancy decontrol provision, the unit turns over, the rent floats to a market rate. You had allowable increases that were set by a local rent control board, and you had an exemption from new construction. And so if you live in a rent controlled unit in Los Angeles today, as I do, your rent is sort of a set by a combination of what the rent control board decides and how long you've been in the unit. And that's kind of the classic American soft rent control, which is where where we are at today.

Shane Phillips 21:34

Yeah. And in World War Two, there's clearly a situation where you have rapidly increasing demand in certain cities, and an inability to respond to that increased demand with more supply. Because all production of any, you know, of any kind, is is really being directed toward the war effort. And it's interesting, actually, that this emerges again in the 60s and 70s, when we're starting to I don't know, maybe this predates it a little bit, but I'm thinking about like the stagflation era, where we have high inflation, the job market's kind of a mess, and so I would imagine that was also affecting supply. There was also down zoning and things that were just regulation was maybe pushing downward on supply. But there's also just macroeconomic things going on where maybe even if development was legal, and it was relatively easy to get a project approved, perhaps getting the financing, and because of things going on in the economy, it might have been difficult to to build the housing people needed where they needed it.

Mike Manville 22:33

I think that's right. And I think, you know, this is, in some ways, a whole other subject about just the changing political economy of development in the US. But like you said in 1940s it was just literally this emergency set of price controls. Rent control happened to be one of them. The 1970s you had, you know, even a Republican president fiddling with price controls. And so they seemed acceptable. But then you also saw the people who pushed for rent control at the local level, particularly in California, but in Massachusetts as well, they started to sound, you know, explicitly against there were people explicitly against development. You know, the Santa Monica Coalition for renters rights, which was sort of a bellwether and push for rent controlled. Santa Monica, they explicitly said they don't like new supply, right? And so this, as you know, your point is that this could have been paired with more supply in in some counterfactual world. And I think that's probably true. But you know, there is a fact that the proponents, for different reasons, became very suspicious of new supply at the same time that they put their faith in rent control.

Shane Phillips 23:35

Yeah, yeah. Well, I think that's probably enough history. We'll probably, we will likely touch on a few other elements of the history in our conversation, especially explaining a lot of the effects. But I do want to get into these effects, because that is the heart of Constantine's paper. Constantine, I mentioned that you identified 26 different effects of rent control that had been studied, and I should note that most of these effects are unintended consequences, not really core to the purpose, or purposes of rent control. Most of the categories did not have that many studies behind them, and you limited your review to effects that were investigated in at least half a dozen published studies, which left you with eight topics. We're going to do our best to go through each but let me just first list them, and then we'll get moving in order from most studies to least, they are rents in the controlled housing stock, mobility, home ownership, construction, housing quality, rents in the uncontrolled housing stock, housing supply and misallocation of housing. First up, let's talk about controlled and uncontrolled rents together. On this, the empirical research is conclusive. Rent control lowers rents in the controlled stock and raises rents in the uncontrolled stock. I don't think we need to do much to explain how it lowers rents in the controlled sector. But how does it increase rents for uncontrolled units?

Konstantin Kholodilin 24:56

Well, I probably provide an example, a recent example. From Germany, from Berlin, because in 2020, in March, actually, a few weeks after pandemic started, a pretty strict form of rent control was introduced in Berlin. Typically in Europe, rent control is the matter of the national government, but sometimes, and we've seen it twice in the last couple of years, sub national governments tried to get in this area. So Berlin decided, although it wasn't really clear whether it was compatible with the Constitution, and one year after the introduction of rent control, actually the this law was overthrown by the Constitutional Court. But from the very beginning, it was this uncertainty. Berlin's government wasn't really sure that it's constitutional or not, and still, they introduced this rent freeze in German. It's called miten Decker. MIT means rent Decker means something like cap. So rental cap and it was a pretty extreme form of rent control, so something which I could denote as first generation rent control. So the rents for the first two years, the rents were frozen. They were fixed, depending on the construction year and equipment at three to 10 euros per square meter per month. Imagine, if it's 100 square meters, I'm not very good with feet, so it's about 1000 square feet, okay? So if you have 1000 square feet apartment, and if the rent is fixed at three euros per square meter, then you will have to pay 300 euros a month, yeah, which is ridiculous. Yeah, it's not bad, but sign me up and okay, it's very nice for for a tenant, but not that nice for a landlord. So they in some cases, the actual rent was much higher than than this legal rent. So at some point, landlords had even to reduce their rent, because you could hardly find an apartment costing 300 euros a month. So typically, it was the difference between legal price, this price set in the law, and the actual market price was at least 2030, 50% so starting from 2022 the idea was that the rents would increase at maximally at 1.3% a year. So imagine that if they kept this low, so in this counter factual world, so the the law were not was not overthrown by the Constitutional Court, and it was if it were kept for a longer time. Imagine inflation rates in 2022 and the maximum increase of rents of 1.3% a year. So it was really a rent freeze. So we did a study on the effects of rent control, and we found, we found these two effects, so rents for controlled dwellings effectively decreased, but there were two exemptions in the law. So on the one hand, the newly built housing was exempted from rent control, and the newly built housing is the one that was completed, starting from 2014 plus. This regulation was confined to Berlin's territory only. So all all the settlements outside of Berlin, they were not subject to this strict form of rent control, and that was the variation that we took advantage of. So we looked at the dynamics of rents for newly built housing and for the housing outside of Berlin, but not far away from Berlin, so that, because in Berlin, you have pretty well developed network of railroads that connect city center to the to the outside areas. So we took the those areas that are well connected to the city center, yeah.

Shane Phillips 28:47

So you can compare new housing to old housing in Berlin and old housing to old housing that is similarly connected outside of Berlin.

Konstantin Kholodilin 28:56

Yeah, exactly. So we found that these uncontrolled dwellings, so newly built dwellings in Berlin, or all types of dwellings outside of Berlin, they experienced a rent increase which is far above the increase that we could have observed in the absence of rent control. And the our explanation was that, well, there are two things probably that might be interesting to you. The first thing is that in Berlin, 95% of housing were subject to rent control. So only 5% of dwellings were not subject these were dwellings built since 2014 so the vast majority of housing was under rent control. And it implies that if rent decrease in for controlled dwellings was, let's say, minus 20% then 95% of tenants would enjoy this decrease in rents. And in Berlin, by the way, the majority of households are tenant households, like 87% of all Berlin's households are renting apartments. So homeowners are just 13% so the vast majority of Berlin's population would was enjoying the decline in rents, while just 5% of all dwellings were experiencing rent increases. So if you compare the negative, negative effect on control trends to the positive effect on uncontrolled trends, then of course, the the first effect is by much outweighing the second effect. So the net effect would be rent decrease. But over the time, you could expect that first new dwellings are constructed that are not subject to rent control. Old dwellings can be demolished because they over the time, they get into bad shape, and landlords could convert the rental dwellings into condominiums. And actually we observed it in the real data, because in Berlin, you if you want to convert your your rental house into a condominium, you have to report it. You have to obtain a permission. So there's statistics on that. And we observed that immediately after introduction of rent control, the number of applications for these permits increased dramatically. So this, this would also lead to a reduction of the segment which is subject to rent control.

Shane Phillips 31:10

Yeah, I guess there's sort of a distinction here where, in a way, the stronger the price control, the stronger the rent control, the more it does immediately. And Berlin seem to be very, very strong right away, whereas a lot of rent controls are just, you know, we're gonna limit how much you can raise rents each year, maybe less than would normally happen. And so over time, rents will go down. And you know, sometimes that will lead landlords to reduce production, sometimes that will lead people to hold on to a unit, even though, you know, their household has shrunk, and they're kind of over consuming, and its leaving less for other people. Maybe less construction is happening for one reason or another. So there's just less housing going on the market as demand keeps growing. All those things can have an effect over time, but it sounds like in this case, in part, just because it was such a strict form of rent control. You saw more of a response in the uncontrolled sector. More quickly.

Was that the rhetorical question, no, no, it's a real question, yes, yes. I think. But anyway, I mean, the astonishing thing that I discovered in my literature review was that, for example, the effect on the rent on control trends and on uncontrolled trends is pretty the same, regardless of whether you take the first generation or second generation, whether you take the USA or Germany, whether you take 1920s or 2020s so That's That's the amazing thing, that you pull together different episodes and the effect is the same. There might be differences in terms of the quantity, but the qualitative effect is pretty much the same, at least on these two on these two effects of rent control. So I'm going to intentionally ask a naive question, and part of the reason I think it's a good question to ask right now is at the time we're recording this, it's actually the day before the election. It's November 4, and we're going to be voting for president and other things. But we're also going to be voting here in California on something called Proposition 33 which would repeal a state law that restricts the kinds of rent control that cities can adopt, and that would allow cities to apply rent control to new housing, among other things. Right now they're limited to units built before 1995 they're limited to multi family housing. There's various restrictions. You can't have vacancy control, which we talked about, but just thinking about the being able to apply this to newer units and different kinds of units, if rent control only increases rents in the uncontrolled stock, why don't we just apply it to all rental units? Would that not solve the problem?

Konstantin Kholodilin 33:54

I think it would even exacerbate the problem. Because the only reason why this exception is made is because the lawmakers do not want to decent device construction. So imagine you introduce trend control for all types of dwellings, new and existing ones. Okay, if you if you already possess existing units, there are not so many things to do with them. So you can probably give up on maintenance. You can try to convert your housing into condominiums, or in some cases, into non resident to non residential purposes, like you can convert dwelling into a doctor's cabinet or a shop, if it's allowed, because you always have, not always, but you often have legislation in place that prohibits you from doing that. You can try to demolish the dwelling again, if that's not prohibited by the law. But if you if we are talking about housing which has not been yet constructed, so what can you do? You can say, Okay, I'm not going to construct because from the very beginning my rental revenue is limited, so I cannot adjust. Cost my rent to the increasing costs to the increasing prices. So why should I do this in the first place? Why should I bother building something so I would better invest in something else than letting my money disappear in the new housing construction?

Mike Manville 35:15

Yeah. I mean, I think you know the like you said, Shane, it's sort of an intentionally naive question. It seems to make sense. Well, like, let's just make all the housing have the law that makes it cheap. But an additional thing happens when you do something close to that, which is that you get a lot of black markets right, which is to say that, yes, the legal price of this housing is only $500 a month. And if you look at what people are actually paying, because it doesn't do anything to change the demand for housing, and it's very hard. You know, you can regulate some things that are easy to see, like, oh, this person's taking this building down and demolishing it. You can't regulate the fact that the landlord just expects some sort of bribe that brings it much closer to a market rate. And so you have this difference between the statutory rent and the rent people are actually paying, and that sort of undermines the affordability goal. But I think to you know, a variation of your question was addressed a long time ago in the rent control literature. Walter block, who's a notorious opponent of rent control, and so he's not the most unbiased person in the world, but he had this nice quip where he said, If you really want to use a price control to lower rents, what you have to do is apply a price control to everything except rental housing, right? Because then everything except rental housing will have a lousy rate of return, and all the capital will flow into building apartments, and you'll have an abundance of supply. But it's the opposite of saying that you want to just put a price control on rental housing.

Shane Phillips 36:36

Yeah, that makes sense

Konstantin Kholodilin 36:37

If I may add, so we know from the history, just the opposite example. So in Brazil in 1920s 1930s the government was very concerned, because most rich people preferred to invest in real estate, because it was a secure investment. And so they didn't really invest into industry, while the government wanted to industrialize the country. So what they did was to introduce rent control. So immediately all these capital flew into into other industries. So they had industrialization right when people have a choice about where they put their money, and you just tell them, you know, you can know for sure you're going to get a lower rate of return in this sector. They're just not going to invest there. If we had a problem of an oversupply of housing. That might be a very rational response. But yeah, that is not the position we find ourselves in across, really, anywhere in the US at this point. And maybe another historical example, it's from 1920s from Germany. So they, they introduced rent control after World War One, and then you could see it in the numbers. The the amount of housing completions decreased almost to zero. What the government had to do was to introduce subsidies to to to incentivize housing construction. So instead of trying to cooperate with private investors probably helping them a little bit to construct more. The government had to take over the whole exercise, the whole task of new housing construction. And that can be a vicious circle. So you stayed regulating at one point, and then you cannot stop. Because you each time you see that your regulation leads to some problem, then you have to solve this problem. Therefore you introduce regulation at another point, and it's a never ending story, so you will always have to regulate at a new point in order to solve the problems created by the older regulation.

Shane Phillips 38:37

Well, we've talked about housing supply and construction a good amount so far, but let's actually talk about the effects that you found. 11 studies found a negative effect on housing construction. Four found no effect, and only one a positive effect. That's, I think, pretty conclusive, but not as one sided as the findings for controlled and uncontrolled rents or the findings on housing supply, in which nine out of 10 published studies find that rent control has a negative effect, and the 10th finds no effect. First, just what is the distinction that's being made here between construction and supply, and could you also explain how rent control is understood to reduce housing supply, and rental housing in particular.

Konstantin Kholodilin 39:21

Yeah, one of the problems of such literature review is that different authors define the dependent variable in different ways, so they give different names, and sometimes it's difficult to find a common denominator. So I prefer to consider separately studies on new housing construction, but even in this case, there are different measures. There are housing starts, there are building permits, there are housing completions, which, of course, it's not the same. It's something similar, but it's not always the same. In case of supply, I am looking at the housing stock, but again, here you can find differences between total housing stock stock of rental dwellings, stock of owner occupied dwellings. So it's not very homogeneous as a group of indicators.

Shane Phillips 40:09

And how does rent control, or how is it understood to reduce the housing supply?

Mike Manville 40:14

Or how could it reduce supply in a situation where it didn't reduce construction?

Konstantin Kholodilin 40:18

Okay, yeah. So the most evident case, of course, is when the construction is reduced and supply will over the time will go down too. But still, even if a new construction is not reduced, you can have reduction in housing supply because, for example, you can convert your housing to non residential purposes, if you are focusing only on rental housing, then again, conversions to condominiums can reduce this rental part. And another possibility is to demolish dwellings. So even if they didn't serve the whole time that they were supposed to serve, they can be demolished to free space for something new, which which is not subject to any form of control, and which can bring you more money.

Mike Manville 41:03

And there's, I mean, there's, you know, many examples of this throughout the US history of rent control, and also internationally. I mean, in an earlier episode, we had Richard Green and his co author on talking about the relationship between rent control laws in India and the higher levels of vacancy that occur as a result of it, and closer to home, you know, when Cambridge is rent Cambridge, Massachusetts, their rent control law ended in the early 1990s by the time that happened, landlords there had held 1000s of units off the market. They had a hard rent control law simply because it was less expensive to keep them vacant than to have someone in them and have to pay the operating costs and so forth.

Shane Phillips 41:41

One other case I think is important, is the case I find myself in, which is I live in a rent controlled multi family building. It's a duplex, but I bought it seven years ago from someone who owned the building and lived in one unit and rented out the other, and that is what I continued to do. So at some point, both units in this building were probably rented but over time, it has just become more valuable these a lot of these units are more valuable to someone who is willing to live in it as an owner than it is to someone who would purchase it to rent it out like I as a potential owner am willing to pay more than someone would be willing to rent it out, in part because of the restrictions they have on who they can rent it to and how much they can rent it for. And in Los Angeles, there's something like seven or 800,000 units that are at least potentially eligible for rent control. I believe multi family built before 1979 etc. I think at least 100,000 of those today are owner occupied, and these were not even these were not condo conversions. They're just rental units that are occupied by the owner Okay, so we have controlled rents, uncontrolled rents, housing construction, housing supply. Next is home ownership. Most studies on home ownership have found that rent control increases the ownership rate, but a sizable minority finds a decrease. What's going on there? What do you think explains these results? Why would rent control increase the ownership rate? I guess I kind of just answered it, didn't I

Konstantin Kholodilin 43:12

Yeah, yeah. In fact, all our previous discussion contributed to answering this question so But to summarize, it's much easier to explain why rent control can increase home ownership. And the reason is that, well, there are several reasons. One reason is that landlords are not satisfied with the reduced rental revenue, so they try to get rid of this housing. They convert it, for example, to condominiums, they sell it to homeowners, and this reduces the proportion of tenants. On the other hand, imagine that you are a newcomer. You're coming into a new city, so you got a job there, but you cannot get access to the controlled wedding, because the the mobility there is very low, because people are not eager to leave these these apartments, because the conditions there, at least financial conditions, they are very attractive. So you are either have to rent an uncontrolled dwelling, which costs much more expensive than controlled dwelling, or you have to buy an owner occupied house or dwelling, even if it implies that your financial burden would be too high. So under other conditions, you wouldn't, you wouldn't think about buying housing. So all these leads to home ownership rate increases. In the wake of introduction of rent control, it's much more difficult to explain why it should lead to decreased home ownership. So I today, I looked once again, through the literature that finds negative effects of rent control on home ownership rates. And I didn't really find except one, two convincing explanations. One, one explanation was that the tenants who live in controlled dwellings find them so attractive they that they don't want to bother. Buying home ownership, because they have everything. If you are homeowner, you have to pay interest, you have to take care of the housing, and not everybody wants it. Plus it will be probably outside of the city center, outside of the CBD, while if you are living in the controlled unit, it's somewhere in the close to the city center, the price is ridiculously low. So why? Why care?

Mike Manville 45:26

Yeah, I think that that's the explanation that I've heard the most, too, is that it's sort of for a select group of tenants that can interrupt the housing life cycle, as it normally happens, and so you you don't graduate to home ownership. And Richard Arnott phrase this as you know, one thing rent control does, it transfers more property rights to the tenants, and they can actually behave like homeowners and start dramatically improving the unit if they want comfortable in the knowledge that they're not going to have to leave. And this all assumes, as Konstantin points out, that they also have a taste for the type of neighborhood their units in. And so we might expect this to happen in Berkeley and Santa Monica and parts of Manhattan, and maybe not happen in LA's rent controlled stock because, you know, some of the nicer neighborhoods with better schools and so forth in Los Angeles tend to be owner occupied. But, yeah, I think it's a very particular set of circumstances where it would actually do that.

Shane Phillips 46:19

Yeah, next up we have housing quality on which most studies find a negative effect. Rent control tends to be associated with lower quality housing. You discussed this a bit in your article, but there's a question of whether lower quality housing is really such a problem. If the lower quality units are also more affordable. People are free to leave rent controlled units when they like, and so the ones who stay seem to be indicating a preference for lower quality, lower rent housing, if the alternative is higher quality, but also higher rent housing. There are, of course, different degrees of low quality, and a shabby unit is qualitatively different from a dangerous or uninhabitable unit. But I think when critics of rent control talk about housing quality, they can tend to gloss over how the quality of many non rent controlled units is higher, because the rents are also allowed to be higher. If you have to choose between a higher quality unit you can't afford, and a lower quality unit you can then that's going to be a pretty easy choice for most folks, or not even really a choice at all. People in that position are just one segment of the renter population, though, and another is people who might like somewhat higher quality housing and cannot find it. But I'm curious how you think about this one, because it seems a little more ambiguous about what lower quality means. Whether you know it sounds at first blush just like a bad thing, but that doesn't seem to necessarily be the case.

Konstantin Kholodilin 47:51

Well, three things. First of all, I agree that your point of view is completely justifiable. So if people prefer to live in poor quality housing because it's less expensive. Why not? But one thing that I find important is that it's a kind of for me, it's a kind of inefficiency, because you you build the housing of a higher quality in order for it to to decay over time and become lower quality. So why didn't you build from the very beginning, lower quality housing? And the third thing, the main message that I'm interested in here, is that it's yet another proof of the fact that nothing comes at a zero price. So when rent control is introduced, the idea is that people pay for higher quality, low price. But over the time, this difference disappears because, due to lack of maintenance of improvements, the real rent, based on the quality characteristics of the housing, converges to the real rent that is being paid. So you cannot overcome this.

Mike Manville 49:02

I think that's a really important point. I mean, I think in part, the emphasis that is sometimes placed on quality is advanced as a an important qualifier to the observed differences in rent, right? Because it's very hard in your standard comparison to fully control for the quality of the housing, especially since it varies so much. It can vary so much unit to unit within a rent controlled building. And so it's important to understand that even if we see an 8% reduction in rent or something between controlled and uncontrolled housing, some of that is probably actually just lower quality. And to your point, Shane, some people may be like, I'm fine with that, but I think in the kind of rent control we have in the United States with the vacancy decontrol. It's also worth remembering that, as Konstantin points out, the quality is going to decline on average as income goes up. Right The longer you stay in the unit, that's when it becomes less and less affordable for the landlord, or less and less desirable, however you want to put it, for the landlord to maintain that unit because they're. In real terms, they're earning less and less money from you, but that's you know, for most people, you can there's going to be some people it's not the case. Some elderly people, things like that. For most people, their earning power is going to be rising at that time. And so that suggests that maybe this idea that they just they want lower and lower quality as time goes on doesn't make as much sense for most of the renting population.

Shane Phillips 50:22

Yeah, that's interesting. The your income and your housing quality are trending in different directions.

Mike Manville 50:26

Well, it's as Konstantin points out, right? I mean, you know, low quality housing can be incredibly important for a city that has a lot of low income people, but you ideally, you would meet that need from the beginning, rather than say, like, well, hang around for a while and your housing quality will get worse, and then the price will go down. But of course, by that time, if things are working well, they'll have more money.

Shane Phillips 50:45

Yeah, yeah. I think it's also important maybe to think about this beyond the boundaries of a single city with rent control. And if we compare Los Angeles to Phoenix or Houston or something, the amount we are paying for the quality of housing we're getting, rent control or not is quite poor. Oh yeah, we're paying a lot of money for quite old housing that even when its newly renovated, it's still 50 years old, is structurally unsound, in some cases, just lots of problems. That is partly just because we've built very little over the ensuing 50 years, right?

Mike Manville 51:22

I mean, there's only so much you can do with the 1940s building in terms of, how well does the disposal work? How well can it accommodate laundry and unit and so forth, things that people really like, and its just, you know, they weren't made for that sort of thing.

Shane Phillips 51:37

Next up is mobility and misallocation, which I think makes sense being discussed together as well, 20 published studies find rent control has a negative effect on household mobility. Just one finds no effect. This is another one that has both positive and negative explanations for why mobility is lower. Could you summarize those different perspectives on reduced mobility? And do you know of any studies that have tried to distinguish, quote, unquote, good immobility from bad.

Konstantin Kholodilin 52:04

Well, typically, people either are looking at the good immobility or bad immobility. So maybe I'm mistaken, but I can't think now I have a study that discusses both of them. But anyway, let's start from the bad immobility. So bad immobility means that you are staying longer time in the same place, and you are not reacting to, for example, to the labor market shock. So if there's wage increase somewhere outside of your city, you don't want to go there because you are afraid that you will have problems with affordability of housing. You won't find a nice, rent controlled dwelling, the place you have is already good for you, so you simply don't react to these wage shocks. Now the good immobility, at least from my point of view, is that you stay longer time in the same place. You can reformulate as residential stability. It sounds a little bit nicer than, right? Than lack of mobility.

Shane Phillips 53:03

One man's e mobility is another man's residential stability, or housing stability, exactly.

Konstantin Kholodilin 53:07

Yeah. So when you leave for a long time in the same neighborhood, you you accumulate social capital there, so you you know your neighbors, you can help each other. You know the the vendors and all the stores and shops around the corner. And this is a social capital, because you interact with the people, and it can be helpful for your psychological health, and it can be even helpful from the point of view of criminality, if you know the person, then the person can either help you in a difficult situation, or can tell you that something bad is happening. So can protect you from some crime, from being a victim of a crime. And therefore, in this sense, the residential stability is a good thing, because you remain longer time in the same place, and you you don't have to give up on this social capital. You won't lose it. You have all your social networks in place, and that's definitely an advantage.

Mike Manville 54:06

The only thing I would say about this is just that, you know, like you said, Shane, one man's stability is another person's immobility. And I think the classic example of the bad mobility, or the bad immobility that you sometimes here is just and this maybe leads us into misallocation people who let their house sort of outgrow them, right? You know, you have this wonderful location, yeah, you have this wonderful price on a four bedroom. And you, you raised your kids there and so forth. But now further on in your life, it's just you and your spouse, or maybe just you, but like you actually would face a substantial penalty for downsizing, because the price you pay for that controlled unit is so low, and so you rationally hold on to it. But you know, there's a, there's a family of four coming up somewhere that would value, that would value that more than sort of like what you would but you don't have to confront that trade off. And so the same opportunities that are given to one generation the next one is sort of inadvertently deprived of them.

Shane Phillips 55:06

Yeah, yeah. I mean, it sounds like the reduced mobility is, to the extent its bad for some people, is something that is harming you. You know, you get a job offer or have opportunities elsewhere, but because you have this low rent, you're kind of, you decide it's not worth it to take advantage of those opportunities. It's, you know, I might like to move into a bigger home to accommodate a growing family. And it's just the gap is so large, I feel kind of stuck. The misallocation is maybe sometimes people are in a position where they're getting a very good deal. You know, there are one or two people living in a four bedroom home. It's not really a problem for them, per se, but it is a misallocation that is causing problems for other people. Who could really use that unit much more efficiently, effectively, it would suit their needs better, and actually, a smaller unit might suit the other people's needs better, but it's just not it's not harm in the same way. I feel like it's annoying maybe to have too many bedrooms. But some people would also be like, Well, I have space for an office. I can, you know, there are upsides too.

Mike Manville 56:08