Episode 83: Local Effects of Upzoning with Simon Büchler and Elena Lutz

Episode Summary: Urban upzonings have been rare across the world, and many of the most significant occurred only in the past 5–10 years or less. One exception is the canton of Zurich, Switzerland, where cities and towns have been relaxing land use restrictions for over 25 years. Simon Büchler and Elena Lutz share their research on the long-term effects of these reforms on housing supply and rents, and the kinds of zoning changes that produce real-world results.

Abstract: This paper examines the effects of relaxing land-use regulations on housing supply and rents at the local intra-city level. We apply a staggered difference-in-difference model, exploiting exogenous differences in the treatment timing of zoning plan reforms as identifying variation. Increasing the allowable floor-to-area ratio (FAR), i.e., upzoning, significantly increases the living space and housing units by approximately 9% in the subsequent five to ten years. This effect is stronger for larger upzonings, for rasters where zoning is binding, and where rents are high. Furthermore, upzoning leads to no difference in hedonic rents between upzoned and later-upzoned rasters. These results show that upzoning is a viable policy for increasing housing affordability. However, the effects depend on the upzoning policy design and take several years to materialize.

Show notes:

- Büchler, S., & Lutz, E. (2024). Making housing affordable? The local effects of relaxing land-use regulation. Journal of Urban Economics, 143, 103689.

- Anagol, S., Ferreira, F. V., & Rexer, J. M. (2021). Estimating the economic value of zoning reform (No. w29440). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Greenaway-McGrevy, R. (2023). Can zoning reform reduce housing costs? Evidence from rents in Auckland. Economic Policy Centre.

- Asquith, B. J., Mast, E., & Reed, D. (2023). Local effects of large new apartment buildings in low-income areas. Review of Economics and Statistics, 105(2), 359-375.

- Gyourko, J., Mayer, C., & Sinai, T. (2013). Superstar Cities. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(4), 167-199.

- Mast, E. (2024). Warding off development: Local control, housing supply, and nimbys. Review of Economics and Statistics, 106(3), 671-680.

- Mast, E. (2023). JUE Insight: The effect of new market-rate housing construction on the low-income housing market. Journal of Urban Economics, 133, 103383.

- Bratu, C., Harjunen, O., & Saarimaa, T. (2023). JUE Insight: City-wide effects of new housing supply: Evidence from moving chains. Journal of Urban Economics, 133, 103528.

- Li, X. (2022). Do new housing units in your backyard raise your rents? Journal of Economic Geography, 22(6), 1309-1352.

Introduction

- “This paper investigates the effects of relaxing land-use regulations on housing supply and rents at the micro-level. Steeply rising rents and subsequent housing affordability problems are a critical challenge for cities across the globe (Gyourko et al., 2013, Knoll et al., 2017). Extensive literature shows that restrictive land-use regulations and the resulting inability of housing supply to react to demand increases are crucial reasons for cities’ current housing affordability problems.1 Strict zoning regulations are also associated with greater segregation (Trounstine, 2020) and reduced regional economic convergence (Ganong and Shoag, 2017). Therefore, relaxing land-use regulations by increasing the allowed floor-to-area ratio (FAR), i.e., “upzoning” has become popular.”

- “Upzoning should lead to a local increase in housing supply, lowering rents in the entire city (Glaeser and Gyourko, 2018). However, the local effects of upzoning on rents are unclear since the amenity effects of more housing supply can be positive or negative (Diamond and McQuade, 2019) … These amenity effects can exist at the neighborhood level, even if the increased housing supply lowers rents at the city level. Thus, the overall effect of upzoning on local rents is an empirical question.”

- “This paper estimates the effects of upzoning on local housing supply and rents. As our unit of analysis, we use 100 × 100 meter raster cells. Estimating the local effects of upzoning is difficult as upzoning is not random. To deal with this endogeneity, we exploit a large zoning reform in Switzerland that started in the 1990s. This allows us to run a staggered difference-in-difference model using exogenous variation in the treatment timing. Specifically, we observe how different municipalities, independently of each other, revise their zoning plans approximately every 15 years. These independent revisions permit us to use a comparable control group that has last undergone a zoning plan revision, i.e., in 2015–2020. We construct a panel of zoning data, enabling us to analyze how upzonings affect housing supply and rents over 25 years. The estimations rely on detailed data for the Canton of Zurich in Switzerland from 1995 to 2020. Given Zurich’s early adoption of upzoning, inelastic housing supply, and heightened housing demand, it provides an instructive study case.”

- “We find that upzonings significantly increase the living space and housing units by approximately 9% on upzoned rasters compared to the control group after five to ten years. Large upzonings incite a much stronger reaction from developers than small ones. The effect on housing supply is also stronger for rasters where zoning is binding, i.e., the maximum allowable FAR is fully utilized. Similarly, the effect is stronger in areas with high rents. Moreover, we find no significant effect of upzoning on local hedonic rents. This is in line with Mast (2021) and Bratu et al. (2023), which empirically show that, in a non-segmented city, the supply of new market-rate units triggers moving chains that quickly reach middle- and low-income neighborhoods, making the rent effect dissipate across space. These results have crucial policy implications. First, upzoning is a viable policy to increase affordability. However, it takes years for its effects to be realized. Second, the effects depend on the specific upzoning policy design. To increase the housing supply meaningfully, policymakers should enact large upzonings on parcels where zoning is binding, and rents are high.”

- “To ensure the robustness of our findings, (1) we apply the Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021) estimator using an alternative control group, (2) use no and lagged controls, (3) omit the rasters in the municipality of Zurich, (4) apply alternative cut-offs for weak and strong upzonings, (5) control for the modifiable area unit problem, (6) check for an anticipation effect, (7) run the bindingness regression with the entire sample, and (8) employ a balanced event time panel. Furthermore, (9) we use two alternative estimation techniques: changes-on-changes regressions with a continuous zoning variable and an upzoning dummy and a doubly robust regression using propensity score weights (Funk et al., 2011).”

Institutional background

- “The Canton of Zurich provides a pertinent setting to study the effects of upzoning. It is divided into 12 administrative districts and 168 municipalities of varying sizes and degrees of urbanization. The Canton of Zurich is centered around the city of Zurich, which is Switzerland’s largest metropolitan area, with 1.5 million inhabitants in 2019 (Kanton Zürich, 2021). The municipalities are very well connected through a dense public transit network.”

- “The city’s cosmopolitan atmosphere and job market attract people from various countries, fostering a multicultural environment. Over 40% of the residents of the Canton of Zurich are foreigners or have a migration background (Kanton Zürich, 2021). The combination of these factors contributes to the socio-economic diversity of the canton. Its population increased by around 18% from 2005 to 2020 (Kanton Zürich, 2021). Zurich’s metropolitan area is also experiencing strong rent and house price growth, making housing affordability a critical policy topic.”

- “Regarding land use and housing policy, Switzerland is a federally decentralized country, meaning that federal, cantonal, and municipal-level institutions are responsible for housing and land use policy. The predominant source of housing in the Canton of Zurich is the private market, constituting approximately 96% of the total housing stock in 2019 (Kanton Zürich, 2021). The remainder is public and cooperative housing. In the Canton of Zurich, more than 70% of households are renters (Kanton Zurich, 2023). During the time of our study, no systematic inclusionary zoning policy was in place (Lutz et al., 2024). Moreover, landlords in Switzerland can terminate existing leases if they want to demolish a building to build new, denser, or higher buildings. The government of the Canton of Zurich aims to promote new housing construction primarily by increasing the FAR within the existing settlement area to allow private landowners to build more housing.”

- “The zoning system in Switzerland works as follows. The federal government provides a national legislative framework with the primary goal that spatial planning must ensure the economical use of the scarce land area (Gennaio et al., 2009) … Subject to this framework, each canton develops a Kantonaler Richtplan, i.e., a “Cantonal Masterplan”, to steer long-term zoning policy (Schmid et al., 2021) … The Canton of Zurich, like most other cantons, delegates the legal power and responsibility of specifying land-use policy to municipalities. Therefore, municipalities primarily control land-use regulations (Mann, 2009, Gennaio et al., 2009).”

- “The process for passing a new municipal-level zoning plan works as follows. In the Canton of Zurich, a municipality’s urban planning department proposes a new zoning plan, for example, by identifying areas suitable for upzoning. Then, the new zoning plan proposal has to be approved (Mann, 2009). Major zoning reforms require a direct vote at the municipal level. Since Switzerland is a direct democracy, all citizens vote on the zoning plan proposal. Minor changes to the zoning plan do not require a direct vote … In all cases, a simple majority must approve the new zoning plan. This makes passing a new zoning plan a lengthy administrative process of several years (Büchler and v. Ehrlich, 2023). Thus, the year of a new zoning plan’s approval is somewhat random.”

- “Switzerland has a by-right zoning system, meaning that once a new zoning plan is approved, it is legally binding. Landowners can build as much as the zoning code allows, or less, but not more (Silva and Acheampong, 2015). Furthermore, Switzerland does not have zoning boards of appeal, which makes it difficult for homeowners or developers to contest zoning plans. Only the municipal legislature can approve changes in zoning (Mann, 2009). Therefore, developers cannot apply for a change in zoning, differentiating the Swiss zoning system from, e.g., the US.”

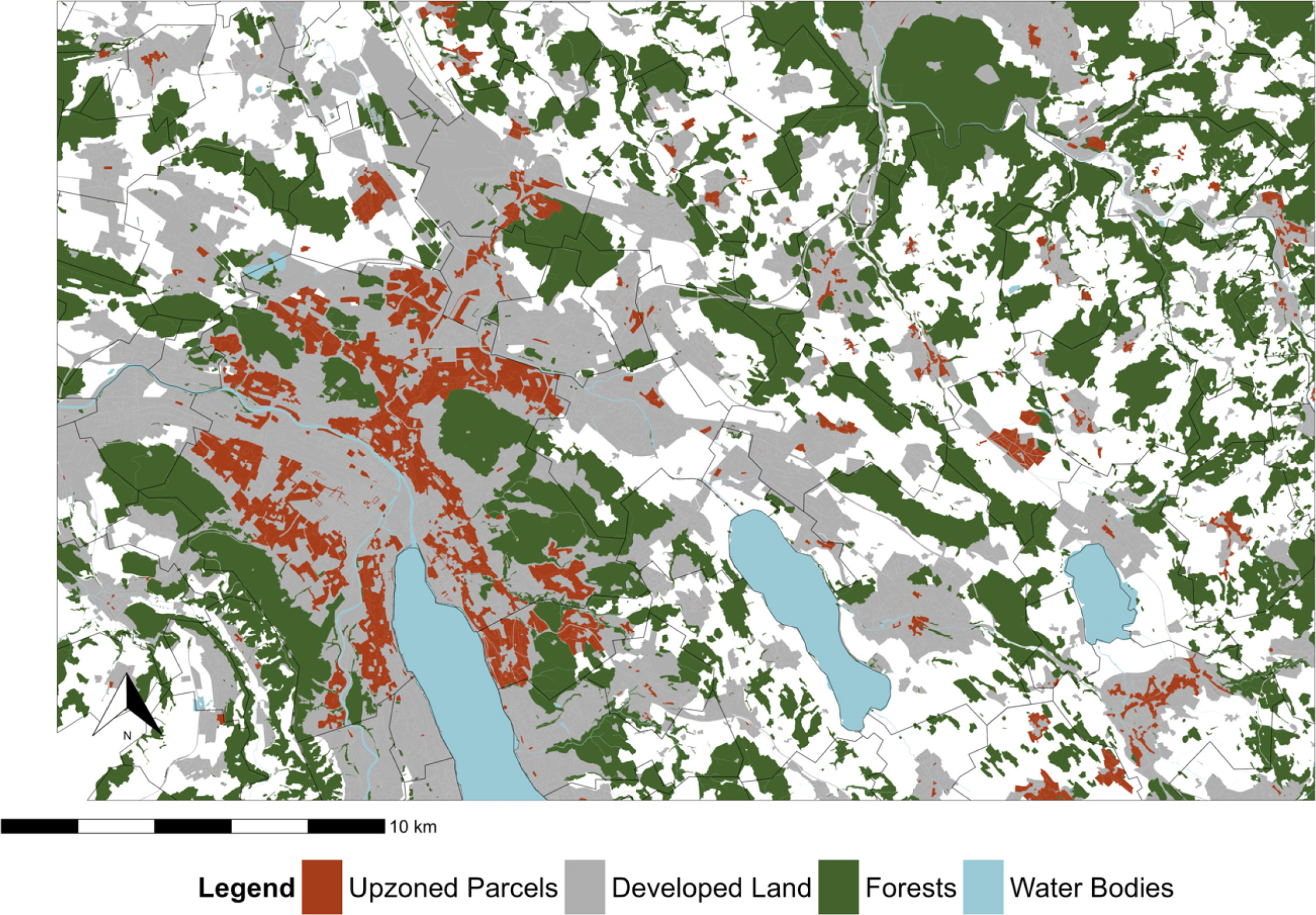

- “Fig. 1 shows the upzonings from 1997–2020. The Canton of Zurich’s 168 municipalities only change their zoning plans infrequently, approximately every 15 years (Gennaio et al., 2009). We run a logit regression to estimate the likelihood of a raster cell being upzoned. Table 1 shows the average marginal effects of the standardized coefficients of this logit regression. These estimates show which factors predict the upzoning in the Canton of Zurich and, thus, contribute to the literature on understanding the determinants of land-use regulation (Glaeser and Ward, 2009, Parkhomenko, 2020). Our estimation shows that the most important predictors of upzoning are the distance to the central business district (CBD), the price housing supply elasticity, and whether the parcels are in an urban or suburban location. Urban parcels are more likely to be upzoned. Regarding the distance to the CBD, our results indicate that most upzoning happens neither directly in the city center nor at the urban fringe. Instead, it happens somewhere between, as indicated by the statistically significant square term of distance to the CBD.”

Fig. 1. Upzonings,1997–2020. This figure shows upzonings, i.e., increases in the allowed FAR, on parcels from 1997 to 2020.

- “In the face of NIMBYism, passing zoning plans that include upzonings in the Canton of Zurich is facilitated by three channels. First, given Switzerland’s low homeownership rate, in many municipalities, the median voter is a renter … Second, Swiss municipalities have ample fiscal autonomy … Third, our analysis shows that most upzonings are moderate, with a median 30.7% FAR increase. Thus, these upzonings seldom transform a single-family neighborhood into a high-rise one, which would spark more opposition.”

Data

- “We construct a panel of 25 years of exact zoning regulation for each parcel in the Canton of Zurich. The independent variable in our study is upzoning, i.e., changes in the FAR that allow for more housing construction. To detect upzonings, we analyze digitized maps of annual zoning plans from 1996 to 2020 from the Statistical Office of the Canton of Zurich. For residential areas, the zoning plans contain 76 different zoning codes. We convert these zoning codes for operationalization into a variable that increases with a higher allowed FAR.”

- “Throughout our main analysis, we use 100 × 100 meter raster cells as our constant unit of analysis. Using GIS, we calculate each raster’s annual zoning change. We exclude 4208 rasters downzoned or zoned out from residential to other uses during our study period. Furthermore, we restrict our analysis to rasters zoned at least partly as residential in 1995. We do so because upzoning refers to increasing density on parcels already zoned as residential and not to re-zoning, e.g., farmland for residential purposes (Freemark, 2020). Upzonings range from 0 to 640%, with a median of 30.7%. In practice, this means that most of the upzonings in our sample allow adding one to three floors. In contrast to Asquith et al. (2021) – who focus on the construction of very large new buildings with 50 or more units – very large upzonings that fundamentally transform the architectural composition of a neighborhood are rare. Since zoning plans are only changed infrequently, we aggregate our data into five-year periods: 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020.”

- “Our dependent variables characterize housing supply and rents. We measure housing supply in two ways: First, we measure housing supply as the log in square meters of living space on raster cell i in year t. Second, we measure housing supply as the log housing units on raster cell i in year t. The number of housing units may be especially important for affordability. To calculate these variables for each raster, we use data from the Federal Register of Buildings and Habitations published by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) … For 2020, the register contains approximately 850,000 housing units for the whole Canton of Zurich, 29.2% of which were built between 1995 and 2020. Using GIS, we calculate each raster’s square meters of living space and housing units.”

- “For rents, we use detailed geo-coded web-scraped asking rent data from the data provider Meta-Sys.6 The data set contains approximately 600,000 postings of rental properties for the Canton Zurich from 2004 to 2020. Besides asking rents, the data set includes comprehensive information on housing characteristics.”

- “We control for raster-specific factors that may change over time and are, therefore, not controlled by raster-fixed effects. First, we use the Federal Register of Buildings and Habitations to retrieve the number of buildings. This allows us to control for the current density level on a raster. According to the Canton of Zurich, density directly influences whether a parcel is upzoned or not (Kanton Zurich, 2015). Second, we control for changes in amenities on the raster and neighboring rasters. This is important as changes in (dis)amenities may be correlated with the changes in the zoning, as, e.g., public transportation and zoning are often planned jointly.”

Empirical framework

- “The main difficulty in causally estimating the effect of upzoning is that the treatment assignment is not random. Upzoning is likely endogenous as urban planning departments upzone the most suitable parcels, i.e., parcels with high density and good public transit access (Pogodzinski and Sass, 1994, McMillen, 2008). Therefore, parcels may experience different unobserved trends over time. To address this problem, we exploit exogenous variation in the treatment roll-out of zoning plan changes in a staggered difference-in-difference estimation. We use last-treated, i.e., treated in 2015–2020, rasters in other municipalities as the control group for upzoned rasters … Since creating a zoning plan is burdensome, municipalities only change their zoning plans, on average, every 15 years.8 Moreover, the number of municipalities that change their zoning plans each year is relatively constant.”

- “The key identifying assumption is that last-treated rasters in other municipalities are a valid control group for early-treated rasters. This assumption requires upzoned areas to be similar across municipalities, conditional on our controls. For example, if the early-treated rasters experience stronger housing demand than the last-treated ones, our results would be biased upward. Table 2 shows that it is the opposite. The last-treated rasters have higher nominal and hedonic rent growth, lower vacancy rates, and are nearer to the closest CBD and train station … To address concerns about a downward bias, we control for raster and year fixed effects, the initial number of buildings, and changes in property taxes.”

- “After estimating Eq. (1) with our full sample, we investigate three policy-relevant aspects of heterogeneity in zoning changes. First, we split the sample into above- and below-median intensity upzonings, where the median is a 30.6% FAR increase. Then, we re-estimate Eq. (1) separately for these two sub-samples. This allows us to differentiate between the effects of large and small upzonings.”

- “Second, the effects of upzoning might differ depending on whether current zoning regulation is binding, i.e., whether the housing supply in a raster is or is not at the maximum FAR allowed by zoning regulations. To capture this, we calculate a “bindingness” measure of the zoning regulation for each raster. Since data on built-out FAR is unavailable, we only rely on the number of floors. Specifically, we compute the difference between the average and the maximum allowed number of floors in each raster under the zoning regulation in the period before the upzoning takes place. Using this measure, we focus on rasters that experience strong upzonings, i.e., FAR increases above 30.7 percent. This ensures that the distribution of the FAR change intensity is similar for binding and non-binding rasters.”

- “Third, we investigate the heterogeneity concerning rents before upzoning. Specifically, we split all treated rasters into above- and below-median hedonic rent in 2005. Then, we re-estimate Eq. (1) separately for these two groups … Since areas with high rent reflect high demand and unresponsive supply, this might signal policymakers where to upzone.”

- “The total local effect of upzoning policies comprises a “direct effect”, i.e., the effect on the treated raster itself, and a “spillover effect”, i.e., a potential effect on neighboring non-treated rasters (Greenaway-McGrevy and Phillips, 2023). Therefore, we also estimate the spillover effects to understand the policy-relevant total effect of upzoning. Upzoning a raster may increase the housing supply on nearby rasters for two reasons. First, some landowners own several adjacent rasters of land. Upzoning one of the rasters can create an incentive for the landowner to build new buildings on all rasters at once. Second, Büchler et al. (2023) shows that owners are more likely to redevelop their properties if recently built nearby properties have a higher FAR … Regarding rents, both a positive and a negative spillover effect are possible (Diamond and McQuade, 2019). ”

Results

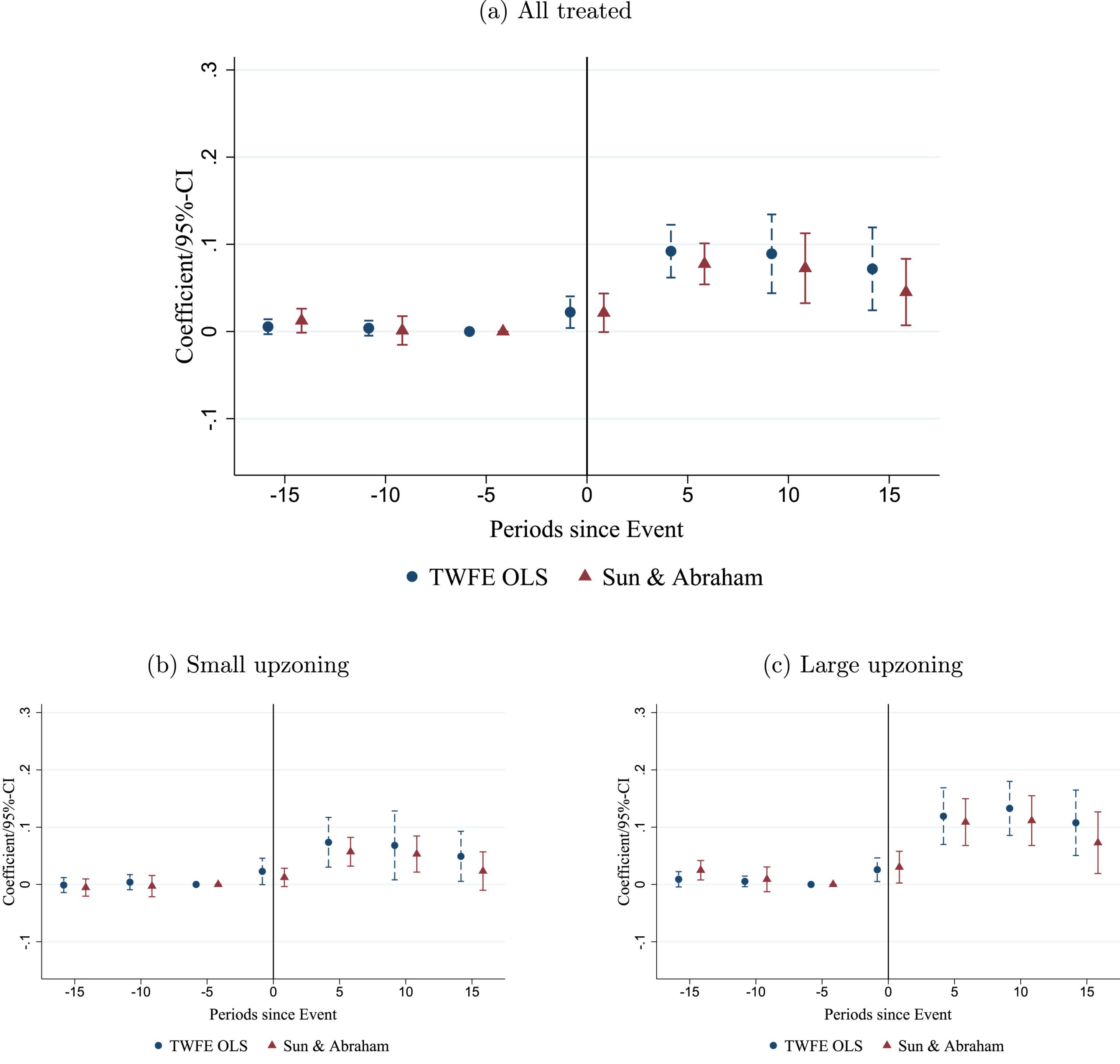

- “Fig. 2 shows the event study results for the change in square meters of living space. The conventional two-way fixed-effects (TWFE) estimator and the Sun and Abraham (2021, SA) estimator cannot reject the validity of the parallel pre-trends assumption. We find that within the first four years after upzoning, there is no significant increase in the living space on the treated rasters compared to the last-treated ones. However, Panel (a) shows that the housing supply increases by approximately 9% five to ten years after upzoning.”

- “Panel (b) shows that small upzonings only increase the living space by 5%–7% after ten years. In comparison, Panel (c) shows that large upzonings significantly increase living space by 11%–13% after ten years. The result that stronger upzonings lead to a much stronger supply response does not depend on the choice of splitting the sample at the median upzoning intensity but also holds for other cut-offs. 15 years after upzoning, housing supply increases in 50% of the treated rasters. Conditional on construction, in 84% of the upzoned rasters, all the additional allowable FAR is built out.”

- “However, more living space may not improve housing affordability if it mainly prompts the construction of larger apartments. Therefore, we also use the change in housing units as the dependent variable. The results are similar. After five to ten years, upzoning increases housing units by 7%–9%. Small upzonings increase housing units by 3%–5% after ten years, whereas large upzonings lead to a 9%–13% increase after ten years.13 These results show that upzoning leads to a significant and economically meaningful increase in living space and housing units. This effect is stronger for larger upzonings.”

- “Next, we investigate the role of bindingness in the effect of upzoning. For example, some rasters may have an average of three floors, even though regulation allows for four floors. The effect of upzoning such a raster may differ from upzoning a raster on which the maximum allowable FAR is fully utilized (see Section 4.1). Fig. 3 shows the event study results for the change in square meters of living space depending on whether the zoning regulation was binding at the moment of upzoning. We focus on rasters that experience strong upzonings, i.e., FAR increases above 30.7 percent … We find that the effects of upzoning on housing supply are much more pronounced on rasters where zoning regulation was binding. Housing supply increases by approximately 30% 15 years after upzoning parcels where the zoning regulation was binding, but only by approximately 2%–7% when it was not binding. On binding rasters, the effect is statistically significant on any common significance level.”

- “Since high rents reflect high demand and unresponsive supply, the effect of upzoning might also differ depending on the rent level before upzoning. Fig. 4 shows the event study results for the change in square meters of living space for rasters above- and below-median hedonic rent in 2005. Ten years after upzoning, the housing supply increases, on average, by 23%–25% for above-median-rent rasters, whereas it only increases by 8%–9% for below-median-rent ones. Even though the estimates are not statistically different from each other, these results suggest that policymakers should upzone high-rent areas to increase the housing supply.”

- “Most upzonings do not lead to any spillover effect on living space and housing units on neighboring rasters.14 Only large upzonings have a weak positive spillover effect. They increase living space and housing units by approximately 5% after 15 years. However, these effects are only statistically significant for the TWFE estimators.”

- “Fig. 5 shows the event study results for the change in log hedonic rents. In contrast to the housing supply, we find no statistically significant effect of upzoning on rents. The 95% confidence interval for the SA estimator ten years after upzoning for all treated rasters is -0.0034 to 0.0138. Thus, it is unlikely that upzonings increase (decrease) local hedonic rents by more than 1.4% (0.3%) compared to non-upzoned rasters. This null result also holds for small and large upzonings and different sample splits. Thus, we find no evidence that upzoning affects the hedonic rent on the treated rasters in the subsequent ten years. Rental prices may change afterward. However, this is unlikely since our analysis shows that most new housing is developed within the first ten years after upzoning.” supply effect. For example, a positive demand effect can occur if upzoning leads to qualitatively better developments … We investigate this possibility by analyzing the effect of upzoning on nominal rents. A local increase in nominal rents would indicate that the new developments are qualitatively better and thus attract wealthier households, making a positive demand effect probable. However, we find that upzonings do not lead to a statistically significant increase in nominal rents.15 We also do not find any spillover effects on rents. Hence, it is unlikely that a local demand effect dominates the supply effect.”

- “There are two potential explanations for this finding. First, upzoning may lead to a positive demand effect that cancels the supply effect. For example, a positive demand effect can occur if upzoning leads to qualitatively better developments. This can attract wealthier households, making the neighborhood more desirable to live in, e.g., due to less crime (González-Pampillón, 2022). We investigate this possibility by analyzing the effect of upzoning on nominal rents. A local increase in nominal rents would indicate that the new developments are qualitatively better and thus attract wealthier households, making a positive demand effect probable. However, we find that upzonings do not lead to a statistically significant increase in nominal rents.15 We also do not find any spillover effects on rents.16 Hence, it is unlikely that a local demand effect dominates the supply effect.”

- “Second, increasing the housing supply on a specific raster may have no local price effect. In other words, rents do not decrease on a treated raster compared to similar non-treated ones within the same regional housing market. This is likely because, within the same non-segmented housing market, the price effect dissipates across the entire housing market … Crucially, this mechanism only works if the city’s housing market is not strongly segmented into separate sub-markets. Thus, by the law of one price, all else equal, upzoning should not lead to any rent difference between treated and non-treated rasters.”

Shane Phillips 0:05

Hello, this is the UCLA Housing Voice Podcast, and I'm your host, Shane Phillips.

This week we're joined by Simon Buchler and Elena Lutz to share with us a very important study on upzoning in Zurich, Switzerland. The Swiss Canton, or state, that includes Zurich also has more than 100 other municipalities, and they've been adhering to a regional master plan in their own ways and at their own paces for 25 years. That gave Simon and Elena the ideal conditions to investigate what happens in areas that upzone compared to similar areas that don't upzone for 5, 10, or 15 years later. Combine that with some premium quality Swiss administrative data and we're in business.

Their findings are as you might expect if you're a regular listener to the show. Upzoned areas built more housing than not-yet-upzoned areas, and areas that upzoned more built more than those that upzoned less. Parcels in neighborhoods with higher rents and less excess capacity prior to upzoning built more than their lower-demand counterparts. And despite all the building, rents didn't increase faster in the upzoned areas.

This all sounds pretty straightforward, and in some ways it is, but it's worth emphasizing how few studies we have on the direct effects of larger-scale zoning reforms, at least the kind of reforms that increase capacity rather than decrease it. Empirical evidence of this quality and depth is really important and not too common, and so we're excited to share it with all of you.

The Housing Voice podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies with production support from Claudia Bustamante, Irene Marie Cruise, and our most recent addition, Tiffany Lieu. As always, send your questions and feedback to shanephillips@ucla.edu. And with that, let's get to our conversation with Simon Buchler and Elena Lutz.

Simon Buchler is assistant professor of finance at the Farmer School of Business at Miami University, which is not in Miami, we may get to that. And Elena Lutz is a PhD candidate in urban planning and urban economics at ETH Zurich, and they're here to talk about their research on the effects of upzoning on housing production and rents in the Canton of Zurich. Their study looks at upzonings over a 25-year period, much longer than cities in most developed countries have been engaged in widescale upzoning, so it may serve as a window into what to expect in parts of the world that are just getting their start on zoning reform. Simon and Elena, thanks for joining us, and welcome to the Housing Voice podcast.

Simon Büchler 3:00

Thank you for having us.

Elena Lutz 3:01

Yeah, thanks.

Shane Phillips 3:03

And I have in my notes here, "Introduce Mike." Hey, Mike. But it's actually Paavo. Hi, Paavo.

Speaker 1 3:09

Hey, Shane, how's it going? Good to see you, Elena and Simon. Thanks for joining us.

Shane Phillips 3:14

Simon and Elena, we always start by asking our guests to give a tour of a city they know well and want to share with our audience. We'll give you each a few minutes, so how about we start with you, Simon?

Simon Büchler 3:25

Sure, Shane. So, I'm going to introduce my city, Bern, which is the capital of Switzerland. It's a charming city with a rich history and well-preserved medieval architecture. Actually, the old town is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It's meandering the Aire River, which CNN shows as the most beautiful river in the world. So it's a great river where you can swim during summer, and on hot summer days, you may find half of Bern swimming in this river. On a beautiful day from the University of Bern, you can see the Alps. So it's a very, very nice city. It's known for its unique plant of history, culture, and nature. Of course, it has a bear park, which symbolizes the city, connection with its emblem, which is a bear.

Shane Phillips 4:11

Is that where Bern comes from?

Simon Büchler 4:13 Exactly.

Shane Phillips 4:14 I don't know my German or Swiss-German.

Simon Büchler 4:17

So also, you might know that Einstein lived there for a couple of years from 1903 to 1905, where he actually was very productive and finished his theory on special relativity. So there's a beautiful Einstein Museum there, too. You can visit his house. So the population of Bern is around 130,000, so it's rather small. Metro area is around 400,000, but it's a culturally very rich city, very beautiful, has a lot to offer. So I invite you all to come visit Bern.

Paavo Monkkonen 4:49

Can I just real quick inject a Bern anecdote, because I got the opportunity, I was invited by the University of Bern to visit, and I agree with Simon, it's a fantastic place. And the museum is my favorite part of a museum that I've seen in Europe to date almost, is this collection of treasure and loot that the Burgundian kings stole for like 300 years. Like Bern used to be a real tough place, and they would loot the neighboring flams and everybody and the looted treasure rooms is a pretty cool museum exhibit.

Shane Phillips 5:21

Elena, how about you?

Elena Lutz 5:22

Yes, I will give you a tour through the city of Zurich. And this is where I'm currently living and conveniently, it's also the city in which our study that we're going to talk about today takes place. I think it's anyways great for listeners to get an overview of the city. So Zurich is the largest city in Switzerland, it has like an area around 1.5 million inhabitants. And it's also the economic and cultural center of Switzerland, many universities, firms are here. And I think if someone came to visit me in Zurich, I would start the day at the train station, which is really right in the center of Zurich. From there, you could walk through Europa Alley. This is a newly constructed part of the city, let's say right next to the train station. And it's also the place where there are lots of headquarters of firms such as Google. But when you walk through it, you get to quite a nice part of the city. So just the downtown area with lots of cute little shops and restaurants and one could have brunch there and try some of the nice Swiss cheeses and breads that I think all the Swiss miss when we're not in Switzerland. And then I think the next interesting stop would be the Landesmuseum. So that's a museum about Swiss history, which is next to the train station. I think it has a really cool exhibition for anybody visiting Switzerland who wants to understand a bit the history of this country. And then next, also as any good Swiss city, we have a lot of rivers and also a lake, so two rivers and one lake. And from the museum, you can basically exit and take a little boat that brings you down the river to the lake, which is very cute. You get to see a bit old part of the city and you end up in the lake where you also have a very nice view on the Alps. I think that's really a beautiful spot on the city. And I think you can also just get off there and walk around the shore and get some ice cream and walk around and see all the locals hanging out there on a weekend. And then next, you could go on Utlieberg. Utlieberg is a mountain on basically on the side of Zurich. And you can go up and have a view over the entire continent of Zurich. And I think that's also nice because you see on the one hand, Zurich, which is very urban, you know, with skyscrapers and kind of like a very urban place. But then you also see that, you know, once you start leaving Zurich, they're really way more suburban and even peri-urban areas. And you see even more of the Alps. And then in the evening, I would go back to an area which is called Hatprücke. So that's an old industrial area, but has many nice bars today.

Shane Phillips 7:51

Paavo, was I the only one when Elena said Swiss miss who thought of the little rolled chocolate things with the white filling in them? Did you miss that?

Paavo Monkkonen 8:01

I thought of that too.

Elena Lutz 8:05

I think I don't know what that is.

Shane Phillips 8:06

It's very unhealthy. Kind of like Twinkies. I think in my head, I just had in my mind that every Swiss city is immediately surrounded by the Alps. And I was looking at a map of Zurich and trying to get a sense for it. It seems pretty flat actually compared to somewhere like Geneva or something like that anyway. Right?

Elena Lutz 8:31

It's a little bit away. I think that's also why it's such a big city there. Because you have actually the space to even develop.

Paavo Monkkonen 8:39

But you can see them like across the lake, right? They're not that far. You can still see them. Don't worry.

Shane Phillips 8:46

Yeah, that is important. I did want to mention something from your paper. You wrote about Zurich. As a major economic and cultural hub, Zurich hosts multinational corporations such as Google, Facebook, and Microsoft, the headquarters of several international banks and insurers, and reputable research institutions, which I thought was very modest to say it yourself.

Elena Lutz 9:08

I had this comment, no, no, no, and I was like, oh my God, that made it somehow.

Paavo Monkkonen 9:13

Unlike some of those other research institutions that are extremely disreputable.

Shane Phillips 9:19

All right. So today's conversation is about an article published in September of this year in the Journal of Urban Economics titled, "Making Housing Affordable? The Local Effects of Relaxing Land Use Regulation." Simon and Elena are the two co-authors. The study makes a lot of valuable contributions about the short and long-term effects of upzoning, and they do this by comparing outcomes in upzoned areas to non-upzoned areas throughout the 168 municipalities in the canton of Zurich. All of these cities were required, or at least many, were required to update their zoning for higher densities, but they were free to do so in different years and with quite a bit of discretion about where they would and would not upzone. And that creates a bit of randomness or variation that strengthens the case that the upzones were the cause of the outcomes that they measured. Breaking the region up into rectangular zones 100 meters on a side, they found that upzoning was associated with an increase in living space and housing units, but no increase in rents. Larger upzonings were associated with larger increases in living space and housing units, as were upzonings that took place in zones with higher rents and where the zoning was more of a binding constraint, which we'll talk about later. They also found that these effects generally take at least 5-10 years to materialize. Part of what makes this research so valuable, I think, is that, for the most part, affordability advocates have to make a pretty indirect case for upzoning based on the evidence. Lots of research shows that more supply is associated with greater affordability, but evidence showing that upzoning actually leads to more housing supply is actually fairly limited, in part because so few places have done it in recent decades. It's not that we don't have any evidence, but we just don't have a ton. Research linking upzoning directly to changes in rents is, I think, even more rare, partly because upzoning has been rare, but also because it's just methodologically challenging to measure. Simon and Elena have managed to do that here, though, and I really do suspect that this study is going to go down as one of the classics in the zoning reform literature. So as we get started here, can you say more about the state of research on upzoning, housing supply, and rents and home prices, the linkages between all of these things? Beyond my very brief and incomplete overview, what did or does the literature have to say about all this, and what gaps were you trying to fill with this study?

Simon Büchler 11:44

So Shane, there's a growing literature on upzoning, just because it's becoming a popular measure. Affordability issues are things that are happening all around the globe, so a lot of cities are fighting with affordability issues. So upzoning, when you say, okay, you have a restricted supply, and the restricted supply is one of the main reasons that you don't have, that the prices are increasing, the natural policy is just, okay, let's upzone, let's make this supply less restrictive. So there is a paper by Anna Golat and co-authors for São Paulo in South America. There's a paper from Greenaway, McRae, and co-authors for New Zealand, Auckland, where they look at that, and also ask if at all, looking at 11 different cities in the US. What makes our paper a bit different is that we have very, very rich data at the very localized level. So we can see each building, how it changed over time. We can see for each plot of land, how zoning changed over time. And the beauty of it is we have the data for over 25 years. As we also talk in the paper, you can see this is very important, because for the upzoning to have an effect, it takes a long time. So those papers, they might find that it decreases rent, that it increases supply, but this is just probably a low level, what they find, probably the long-lasting effect is much bigger. As we see, even in our study for 25 years, we're probably not capturing the whole effect. So I think this is one key thing in our study. The second is we can go very, very, very local. And a lot of people are getting worried about upzoning. Does it lead to gentrification? Does it increase amenities? Will it increase rents for everyone? All these questions that we can answer with this study.

Shane Phillips 13:35

Yeah, I think the local focus is a really important one and work like the Asquith-Maston-Reed on neighborhood effects of new housing on rents is really important. But as you say, your data is very rich and you're really able to look at the building level over time and breaking up this whole region into these hundred by hundred meter, what you call rasters.

Elena Lutz 13:59

Maybe just to add to this what Simon just said, I think another strength of the paper and the data that we have is that we can also look at heterogeneity in upzoning. So we can look at how does the effect of upzoning differ depending on whether we upzone a lot or a little, depending on whether we upzone in areas with high rents or low rents. And I think that this is very instructive and interesting for policymakers when thinking about how to design upzoning policies. And also, for example, when thinking about how to design inclusionary zoning, how much density bonus would we have to give to people so that the response in upzoning is still strong. So these kinds of questions.

Shane Phillips 14:39

Yeah, yeah. I think there's one or two studies or reviews of multiple studies of upzoning in the US and they'll combine like an ADU reform with a much more aggressive reform in another city and just kind of pool them all together and say, what is the effect of upzoning? And that is a contribution, but it's kind of, you can have the really weak upzones washing out the effects of the much stronger ones. And so being able to see within one kind of larger area, what is the differential effect of these is important. So we're already kind of getting into the study design, but I want to start off with a little bit of background on the Canton of Zurich and how upzoning works there. So I'm just going to ask three questions in series and you can just kind of get through all of them. The first, what is a Canton? Second, what distinguishes the Canton of Zurich from the other 25 Cantons in Switzerland? And third, why did the municipalities in the Canton need to change their zoning? What's motivating them or requiring them to do so?

Elena Lutz 15:43

Yes, so a Canton is just a Swiss word for a state. So just like the US, Switzerland is quite a federally decentralized country with a strong role and fiscal autonomy of states and municipalities and a Canton is a state. And so we're basically looking at the state of Zurich, which is itself divided into 12 districts and 168 different municipalities.

Shane Phillips 16:07

This is a lot of jurisdictions for a country with 9 million people or so?

Elena Lutz 16:12

No, no, it's a very local thing. It's a very local thing. That's really true. Then I think you can kind of think of it maybe a little bit in terms of like the greater Boston area, for example, which I think is of maybe a similar size in terms of municipalities, I thought. And how does the Canton of Zurich differ from other Cantons? Here I think the main difference is that the Canton of Zurich is the largest in terms of population and also the most urban one. And then when we think about why now do municipalities in the Canton of Zurich need to change their zoning, then we basically have to go back a bit in history and start, I think maybe like in the mid 90s, where you have to think that Switzerland overall is a country also with many rural areas, with a lot of farmlands, a lot of mountains, the Alps. And what happened in Switzerland is that there was really a strong problem of urban sprawl. So for example, in the more rural areas, people were constructing a lot of land quite far away from the existing settlement areas. And this then started to raise concerns on the national and local level politically to say, okay, this is not very ecological for ecological reasons. We need to change the way that we do our zoning and where we construct new housing. And therefore, Switzerland then started to pass reforms that urged municipalities to densify already existing settlement areas rather than constructing on the green field and committing urban sprawl.

Paavo Monkkonen 17:40

Seems like a good idea.

Elena Lutz 17:43

Seems like a good idea. Yes. And it really came, I think, primarily, originally primarily for almost ecological concerns to protect the Alpine landscapes, to protect cultural land for farming. So I think this was the logic where this push came from. And then over time, we started to have regulation at the national level that imposes basically on controls and also on municipalities to densify existing settlement areas when they want to create more housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 18:15

Can I just ask, I mean, if it's worth talking about, if anecdotes will be sufficient, because it's not really part of your paper, but just about this process of telling the municipalities that they had to do some upzoning, like I imagine there were some challenges and pushback from different municipalities and kind of how did the Canton government enforce these rules?

Elena Lutz 18:36

I think this strongly depends on where in Switzerland you are. So I think, for example, in the more rural areas, you know, where this legislation originally comes from, they, until today, are basically struggling to implement a little bit these regulations, or maybe I shouldn't say struggling, but they're working on implementing these regulations because they often even have to zone back, like they have to zone land that they zone for housing back to agricultural land, which of course is not very easy to explain to a landowner. And then in the urban areas, there may be some more incidents of NIMBYism where maybe people didn't want the upzoning, but it really, I think, depends a lot on the local situation.

Simon Büchler 19:21

If I can add here, how they did it, they did a Cantonal Master Plan and deciding which municipalities are going to upzone, which not depends on the projection of population growth. So if you are a municipality that is growing, you should upzone more than a municipality that is losing population. Those are the municipalities that are making the opposite, not taking land that was supposed to be built up and converting it back to agricultural land. So that was the first thing. And the other thing I want to highlight is that the Canton of Zurich houses the city of Zurich, which is a global city, a city with a lot of housing affordability issues. And if you take the superstar cities paper by Jo Joek and co-authors showing that superstar cities are cities that have a very inelastic housing supply and very rapid demand growth, Zurich gets into this category. So I think this is important because this makes our results also applyable to other cities, superstar cities around the world, which are facing the same housing affordability issues.

Paavo Monkkonen 20:23

And so even within the Zurich metropolitan area, they use this process of giving bigger targets for growth to the municipalities that were already growing more. So it's kind of a pragmatic way to do it because these are the places that aren't restricting growth. So they're more likely to allow for more of it.

Elena Lutz 20:40

Also one should say it's always a negotiation, right? There's not, how can I say this? It's not like a formula. Yeah. There's not like an exact formula, but the Canton will believe, for example, the Canton of Zurich is growing in population. They know that they are growing in population and that they expect to grow also in the future. So the Canton government tries to come up with a kind of a long-term guiding plan of how we should be able to accommodate these additional people that come to Zurich because there's a lot of jobs and universities and everything. How can we accommodate them in the existing settlement areas and then kind of in a back and forth process, one could say, comes up with how and where densification should occur.

Shane Phillips 21:28

Yeah. Let's get into the upzoning process a little bit more and talk about what this looks like among the municipalities. Paavo and I actually talked about this a little bit with David Kaufmann and Michael Vicky about this in episode 70. And it seems there's just a lot of direct democracy style voting in Swiss cities. But I want to get a bit more into the weeds of how this works and why it may be important and maybe even why this style of voting could be better for reforming zoning than having your representatives do it. Could you describe a little bit about how that works in Swiss cities?

Elena Lutz 22:05

Yeah, so I think this is a great moment to take a little step back and explain a bit how the zoning system and approving new zoning plans works in Switzerland. So how doing a new zoning plan works is that usually first the urban planning department of the city will elaborate a new proposal for a new zoning plan. And then as you correctly said, Shane, citizens need to agree with this new zoning plan. And if it's a bigger change in the zoning audience, then this requires a direct vote by the citizens. And here it's really something very special about Switzerland that we are a direct democracy. So this means that when a new law or something like a new zoning reform needs to be passed, citizens need to vote on it directly. So you can imagine in practice that if a new zoning plan or a zoning reform is passed, the government will send you a brochure to your home that explains you this new proposal for the plan. And then you can vote by a post saying yes or no. So agreeing or disagreeing with the proposal and the proposal will be accepted if at least 50% of voters accept a proposal. So this is how this would work. Then smaller changes, sometimes it can just be passed by the municipal parliament. So again, it depends a little bit on the municipality and so on, but overall, this is how it works to accept a new plan.

Paavo Monkkonen 23:36

So I imagine a lot of times people reject the proposal and then the city can come back with another proposal. The city can come back with another proposal. I mean, are there any cases where they reject it eight times and then get it approved or is it usually a couple of times before people approve it?

Elena Lutz 23:52

I mean, usually it's not something like eight times I haven't heard of because usually you want to maybe come back once or something like this, but not so many times because usually you want to think that when there's the popular vote, you need to respect the popular vote is what we would say.

Paavo Monkkonen 24:08 Interesting. Okay.

Shane Phillips 24:10

I think my intuition is that direct democracy is going to make it harder to pass zoning reform, but at some level it does sound like if most of a city is not being up zoned at any given time and even if you have kind of nimby people, as long as they're nimby, not in my backyard and not banana build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone, then they might be happy to vote for a zoning plan that puts the additional capacity somewhere else, right? Even if they're not really excited about building more generally, whereas I feel like actually when you have representatives doing this stuff, interest groups can carry a lot of weight. I'm sure also the fact that 70% of Zurich residents are renters helps a bit too.

Elena Lutz 24:58

Yes. I think when we want to think about how the political system in Switzerland with the direct democracy aids or prevents changes in zoning from being approved, I think there are various reasons why one could believe that it may actually be, or this context in Switzerland may actually be helpful even though this is beyond the scope of our paper. So yeah, that's more now something that we believe rather than something that we investigated in this paper. But I think something that is noteworthy about Switzerland is that new zoning plans, they need to be approved at a municipal level. And as you said, usually the zoning change will not be everywhere in the municipality at once. And I think there's also research, for instance, a recent paper by Eben Mast that shows that if you take those decisions on zoning on a higher geographical level, that then it is more easy to approve changes in zoning rather than taking them at like the ward or the neighborhood level. And I think this is very much the case in Switzerland. Yeah. Divide and conquer. So this is one factor. A second factor, I think, as you already also mentioned, is the relatively low home ownership rate in Switzerland in international comparison. So in our study area in the continent of Zurich, around 70% of people are renters. And I think also in Switzerland, it's way more normal to rent across the income spectrum. You could be very rich, you could still be renting. And I think this also helps potentially to lower those interests in NIMBYism, keeping up home values. I think there are more people in Switzerland. The median voter usually would be a renter.

Paavo Monkkonen 26:39

And I wonder, I mean, we're going off on this tangent probably too long, but I'm also thinking like the preserve the countryside argument for these up-zonings seems like it would resonate strongly. I mean, I know some Swiss people, not very many, but I think the connection to nature and people have access to the countryside because there's a good public transportation. You can take the train to the Alps, right? And so like that preservation motivation is probably there too.

Elena Lutz 27:05

No, that is definitely there too. And then I think a third factor that is also, I guess, a little bit important is that also for the context of the study, we need to think that it's not extreme up-zonings that were done, right? It's not that we start at a single family zoned neighborhood and then all of the sudden we convert it into a very dense multifamily home area, but usually I think just for historical reasons, many areas in Swiss cities and also in Zurich, they are just multifamily already. They're already relatively dense. And I think acceptance of densification is also just higher in these areas that are multifamily to begin with. So I think that's also something that makes people more prone to accept zoning changes in the context of the study.

Shane Phillips 27:51

All right. Well, I think that's probably enough context for this study design to make sense now. So let's talk about how this was all put together. Tell us how you set things up so you could estimate the effects of up-zoning, making use of different timing of these zoning plan updates, these hundred by hundred meter rasters, and some very high quality zoning and building data. So what does that all look like?

Elena Lutz 28:13

Yes. So the key challenge in this project really was to overcome potential endogeneity of up-zoning. And what I mean by this is that, of course, the location of up-zoning, so the choice which parcels are being up-zoned or not is not random, but there's a reason why the urban planning department will choose a certain parcel to be up-zoned, another one will not be up-zoned. And therefore, this means that we could not, in our study, compare areas that were up-zoned to areas that were not up-zoned because they are fundamentally different. And there is a reason why one area was up-zoned and the other area was not up-zoned. And then the particular setting of the zoning reforms in the continent of Zurich, however, gave us an opportunity to kind of overcome this usual limitation of studying the effects of up-zoning. Namely, what happens in the continent of Zurich is that you have these 168 different municipalities that all kind of follow the same logic in choosing which areas in their municipalities to up-zone and which ones not to up-zone, and then they change their zoning plans in different years. So for example, you could imagine one municipality will change the zoning plan in 2005 and another one in 2010, both times following the same logic when choosing certain parcels for up-zoning.

Shane Phillips 29:33

And that logic is essentially dictated by federal policy, by the Cantonal Master Plan, things like that?

Elena Lutz 29:39

By the Cantonal Master Plan. Exactly. So the logic on choosing which parcels to up-zone, that is kind of guided by the Cantonal Master Plan that encourages, for example, up-zonings that are close to nodes of public transit because they want to promote the usage of public transit and using less the car. We did a little analysis to see which factors predict up-zoning in our sample, and we found exactly being close to the train station predicts it. Also being in an area that is already relatively dense also predicts it. So there are some kind of common factors that seem to guide the choices of policymakers when choosing which areas to up-zone. And then back to the setting that we then use. So in the paper, we use what is called a staggered difference-in-difference model, and this means that we can compare parcels that are up-zoned. All the parcels are up-zoned, but some are up-zoned earlier and some are up-zoned later. And how the design works is that we compare parcels that are up-zoned earlier, for example, a parcel that is up-zoned in 2005 to a parcel that is up-zoned later, for example, in 2010. And this setting enables us to perform a difference-in-difference estimation to understand the effect of up-zoning. Then regarding the data, we started by using historical zoning maps. We have historical zoning maps for the entire continent of Zurich over 25 years. Every year we see what was the current state of zoning on all parcels in all municipalities. And we can then use these maps to identify where up-zoning took place and to identify where new housing was built. However, the polygons in the zoning plans, they change over time. And so to find a unit of analysis that was constant over time and also kind of more logical to interpret, we decided to use these 100 times 100 meter rasters. We also did a robustness check using some larger rasters, so you should not interpret too much into the size specifically of this 100 times 100 meter raster, but it was just something to help us to have a unit of analysis that is constant over time.

Shane Phillips 31:47

So it's just dividing the whole area up into these 100 by 100 meter squares. Hundreds or thousands of squares, each kind of like a mini neighborhood or something.

Elena Lutz 31:58

That's exactly it. Exactly. I think you can almost think of it as like a very large parcel, like a couple of parcels grouped together. So it's still quite small, 100 times 100 meters. So we wanted to be sure that we can look quite locally at the effect of zoning. So that's why we chose like a relatively small size of the raster in our main analysis and then used a bigger one for robustness in the appendix. And next, we're also able to combine the zoning data with data on all buildings and with data on rent prices. So for the buildings, we use data that is from the Swiss building census and just has information on all the buildings, where they are, and how much units and square meters of housing space or living space they have. And then for rents, we use rent data that starts in 2005 and is again at the unit level and it comes from when rental listings are posted online for a specific unit and then they're geo-coded.

Shane Phillips 32:53

All right. So getting into the results, the direct effects of a successful upzoning should be more homes and more total floor area. And that is exactly what you found. Compared to the not non-upzoned, but later upzoned rasters, how much more living space and housing units were added in the upzoned rasters or the upzoned areas? Let's just start with the overall numbers and we can get to the different results for smaller and larger upzones later.

Simon Büchler 33:22

Perfect. So yeah, the overall numbers, if you compare upzoned with not yet upzoned parcel, you get an increase of 9% in housing supply, meaning 9% in units or also 9% in square meters. So the results are very similar. What does this mean? 9%. On a hundred by hundred raster, we have around 1,500 square meters of built living space. For the American audience, you can just multiply it by 10 and you'll get square feet more or less. So 1,500 square feet, which is around 18 units. So a 9% is an additional one and a half units, an additional 150 square meters of living space in those areas. Just by being upzoned, a dummy, zero if it's not upzoned, one if it's upzoned, not taking into how strong the upzoning was.

Shane Phillips 34:13

And just to be clear, we should interpret that as the amount of living space and housing units is growing around 9, 10%, not it is growing 9 or 10% faster than the non-upzoned areas, correct?

Elena Lutz 34:29

Exactly. I mean, so the coefficient is the estimated difference in housing. So it's not a growth rate, it's the housing stock, but there is over time 9% more housing stock compared to the not upzoned or compared to our control group.

Shane Phillips 34:43

And that's pretty significant. Yeah. You mentioned the amount of residential square footage or square meterage and number of housing units increased more in places that were upzoned by a greater amount. The median upzoning was for 30.7% additional floor area. So half the rasters that experienced at least some upzoning were upzoned by more than that and half were by less. Did you essentially just sum up the total square meters that were allowed if every parcel in that raster was developed to its maximum capacity before and after the zoning change and then just divide that new higher zoning capacity by the previous lower capacity? So just for an example, if all the parcels together could be built to a hundred thousand square meters before the rezoning and then 150,000 square meters after that, that would be a 50% increase. Is it as simple as that?

Simon Büchler 35:42

More or less, it's a bit more actually simpler. We're just looking at the floor to area ratio. Floor to area ratio, if you were allowed to build a FAR of two and you increase it to three, that was an increase of 50%. In reality, this translates to exactly what you said, right? From a hundred thousand square foot to 150,000 square foot. So this is a reality, but the measure that we see is actually much cruder than that. We see the difference in zoning and you have the different FARs and we look at the FAR measure.

Paavo Monkkonen 36:14

So you don't have data on what's already there in terms of what's built out?

Simon Büchler 36:17

We do see what's already there. We always observe what's already there.

Shane Phillips 36:21

Yeah, this is just for measuring how big the upzoning was to determine whether they're there.

Elena Lutz 36:27

Yeah. I mean, to clarify, yes, I think we follow exactly the approach, as you were saying, that we look at the maximum allowed FAR before the upzoning and then we calculate the percent increase in the maximum allowed FAR after the zoning compared to before.

Shane Phillips 36:42

And within a raster, if you have multiple parcels, it's not necessarily the case that each of them is upzoned by the same percent. One might not be upzoned at all. One might be upzoned by a hundred percent, and then you have to average that out based on the area within the raster and all that, I assume.

Elena Lutz 36:56

Exactly. So it was a lot of work. Yeah, but we take those historic maps, overlay them with the raster, and then we find out, for example, if a raster is crossed by two polygons and one is 30% and one is 70%, then I make the weighted average of that.

Paavo Monkkonen 37:17

Love me some proportional allocation.

Shane Phillips 37:21

Okay. So to reiterate, a small upzone is any raster where the floor area increased more than zero but less than 30.7%, and that's the allowable floor area, what the zoning allows. And a large upzone is one where floor area increased by more than 30.7%. Coming back to your measurement of living space and housing units, how did the changes compare in areas with small upzones versus large ones?

Simon Büchler 37:46

So we find that the effects are much larger for the large upzonings. And the 30%, just to put it in perspective, this is a building with three floors and now you're allowed to build four floors, right? This is a 30% increase. So what we find is that the effect of upzoning on strong upzonings on the ones that are above 30%, they go from 30% to up to 600% are basically double the effect of the ones that are small upzonings, below 30%. So we're talking from 6% versus 12%. So in the large upzonings, we get a 12% increase versus around the 6% increase in the small ones. So this is double the effect. It's much larger.

Paavo Monkkonen 38:31

I can imagine that if you go, you know, a 600% increase is much more likely to induce construction than a 100% increase, right?

Simon Büchler 38:39

Totally. So we did some heterogeneity. We have different ones in the robustness test. We did much stronger ones. The problem is we don't have a lot of 600 or 640, right? So there's no control. Most of them are concentrated around 30, 50. So we don't have a lot of those things. So we went much stronger, but then we started running out of observation so we cannot do it. But we do have a robustness test where we go higher up. I think it was 80 or something. Around 50%? 50% it was, yes. And we see that the effect gets stronger and stronger, which is what would you expect.

Shane Phillips 39:14

Right. You also found that more housing units and living space was built in places with higher rents and with zoning that was more binding. Can you quickly explain what it means for zoning to be more or less binding as you measure it and give us some sense for how big a difference these things make on your outcomes? Like did rasters with higher rents or more binding zoning build a lot more or maybe just a little bit more, but enough to be statistically distinct from other kinds of areas?

Simon Büchler 39:43

So their defect is even larger, but let me first say what binding means. If you're in a raster allowed to build up to three floors and you see that the average floors that were built are three, this is binding. So they build already everything they're allowed to build. In some areas, they're allowed to build two floors and the average is 1.5. So it's not yet binding. They could actually add in some plots a floor here, a floor there. So this is what we saw as binding. And this is the measure that we observe. We observe how many floors are built and it's a crude measure of bindingness. So we don't observe the actual FAR, but it's the best way we can do. And it's, I think it's a good enough measure to see where it's binding or not. Now the bindingness also correlates very strongly with higher-end places, right? Because both are driven by demand, you know, if demand is high, you're going to build up the maximum you can. And of course, if it's already binding, it means the supply is inelastic, the prices go up. So those are also the places with high rent. So the binding measure and the rent measure, the correlation is 74%. So 74% are the same rasters. One of our referee asked us to do the high rent and low rent measure, because I think it's a much easier way for policymakers to see where should we up zone instead of looking at how binding is the zoning in these places. Let's just look at high rent, low rent, right? And I think that was a great measure. So it's basically measuring the same, but it's much easier to understand. So just to give you some numbers, how the effects differ in the binding areas or in the high rent areas, we see up zonings and effect on the housing supply of 30%, three zero versus around two to 3% in the non-binding. So it's even much more than strong up zonings to weak up zonings. With the rents, we have less observations. We don't observe the rents for the 25 years. So our observations are a bit lower. So we have very large confidence intervals, but still the differences are huge, but for rents are not statistically different because the confidence intervals are very large.

Shane Phillips 41:55

And I do want to highlight this or underline this because I feel like we keep seeing this in new studies that come out that, yeah, developers want to build where rents are high. But a lot of people think it's exactly the opposite. The developers specifically target low income areas because that's where land is cheaper, for example. And that's not wrong. Land is cheaper there, but in a metro area, the cost of development in every other respect is pretty much the same and only the land costs are higher in some areas. But the places with higher land costs also have considerably higher rents. And usually that makes the bigger difference. The reason we tend to see more development going into lower income areas here in US jurisdictions and I think in many other places is because that's, in many cases, the only place where it's legal to build more. And so you were able to actually look at cases where they up zoned higher rent areas as well, which is great. All right. So that is the effect of up zoning on housing production. More living space and housing units in up zoned areas and larger increases in areas with large up zones than smaller up zones. And more production in places where rents are higher and where zoning was previously more binding. That by itself is already good news since Switzerland has these important goals for reducing sprawl and increasing transit use. So it is successfully using zoning changes to direct growth in ways that achieve that. But another major goal of up zoning is to improve affordability, certainly in the US, if not in Switzerland, or at least not when Switzerland started on this. And we expect places that build more housing to be more affordable than those that build less, all else equal. That's not quite what you found or maybe not quite what you measured. So help us understand what you found when you measured the effect of up zoning on rents.

Elena Lutz 43:46

Yeah. So when we measured the effect of up zoning on rents, first the findings. So we found that up zoning does neither increase nor decrease rents. So up zoning happens, more housing is produced in these areas, but rents don't increase or decrease. Now, how can we make sense of this? So I think here it's very important to consider a couple of factors. So the first one is that we look at local rents, right? How can we imagine this? We look at an empirical strategy that compares parcels that were up zoned and where new housing is consequently being built to similar areas where up zoning has not yet occurred and where therefore also not as much new housing construction is taking place. And then I think it's important to note in the Swiss context to make yourself kind of a mental image of what is going on. So these are areas that are up zoned, new housing is built, and this new housing in the context of Switzerland is often quite nice new housing. So we, when we set out to do the study, we were actually expecting that maybe up zoning would raise rents locally due to this new construction, because maybe this creates positive amenity effects in terms of nice new housing, maybe richer households move into these new buildings. So I think even though we don't find that up zoning decreases rents locally, for us it was already like a surprisingly good news that up zoning did not increase the rents compared to these other areas.

Shane Phillips 45:14

Mm-hmm. Even from like a composition effect or something like that of just having nicer housing now, you might expect rents to be higher purely on that basis.

Paavo Monkkonen 45:22

It's important to clarify, so the rent data is median list rent in a place, right? So it's not like a quality controlled rental index or something or repeat rent index or what is the rent data?

Elena Lutz 45:36

The rent data comes from online listings. So what we basically compare is rental units being posted online, which can either be in areas that are up zoned or in areas that are not yet up zoned, right? And it's going to be the rental price that someone is posting online when they are having an apartment that is free for rent. And then we do use both kind of this more crude measure that is nominal, but we also have one that is hedonic. So that controls for housing characteristics such as what is the building age and so on. So to take out this factor that new housing might just per se be more expensive. And yes, so I think just to say a little bit more about our expectations, so we were not necessarily expecting that up zoning would bring down rent prices a lot in the areas where it occurs, but we were more expecting that it would trigger moving chains of some households moving maybe into these newly additionally built units to the up zoning, which may then kind of citywide dissipate and take a little bit of pressure out of the housing market.

Shane Phillips 46:43

Yeah. Can you say a little more about that dissipation and maybe the role that market segmentation plays or doesn't play in all of this?

Simon Büchler 46:50

Yeah, sure. So there are new studies by Mastem Brato showing these moving chains. Basically the idea is that you build a new house and since, as we heard, the up zoning was also in high rent areas, high income people move in, but they vacate their house where other people move in. And so if you don't have a segregation in the city, this moving chain filters down to the lowest income people. Now, if you are in a very segregated city and for example, the Asquith paper, they look at low income places and you build up, then the moving chain is very short because there's segregation. Nobody, the people who move out there, there's no lower income to go, right? In our case, the income was very high where people move in, so you have this long moving chains. So you see that kind of dissipation of rent over the entire city. This goes with a very simple monocentric city model along some move mills model where people commute to the CBD. It doesn't matter the density you are, it just matters the distance from the CBD. So if you up zone half of the city on this side, you're going to have a price equalization of per square meter per square foot. So this is the law of one price. So in our case, as Elena correctly mentioned, we look at the local rent effects. So to capture the overall rent effects, we would have to need a generic equilibrium model. And even we thought about doing that, but even doing it for the Canton of Zurich wouldn't be enough because the commuting area, so the labor area is just already bigger than the Canton of Zurich. There are a lot of neighboring Cantons where people live and they commute to Zurich and you would have to take them into account too. So we're thinking of doing a project of taking whole of Switzerland and doing a generic equilibrium model where we can actually measure the effect of rent. But unfortunately, some Cantons are a bit delayed in digitizing the zoning data. So we don't have the zoning data for all the Cantons yet.

Shane Phillips 48:48

Well, if you ever get it, you might be our first repeat guests. If you ever publish that paper.

Simon Büchler 48:54

We're waiting. So they have to do it. By law, they have to digitize it. So this is our hopefully follow-up project that we're thinking with Elena. So we cannot say something about the whole rent on the Canton. But if you just take basic logic of supply and demand, if you assume that supply increased and that we show supply increased, then all else equal, this means rents in the Canton of Zurich declined. Now, you also have to take into consideration the fact that I said Zurich is an open city. The Canton of Zurich is an open place. So it also depends what the neighbor Cantons did. But now assuming that everybody in Switzerland up-zoned, these up-zones did lower the rents. This is very hard to explain to policymakers because even though we've seen these up-zonings and we've seen which basically helped increase the supply, the supply never matched the demand. The demand is increasing much more than supply. The supply is still very inelastic. And you can see that, okay, this is a step in the right direction, but it's still not enough. People are just seeing prices increasing and they're saying, but this up-zoning didn't help anything. Prices still did increase. And I think the New Zealand study by Greenway McRae, it's the same thing. Rents in Auckland still kept increasing, they just increased less than the other places that did not up-zone. And that's the same argument we want to make here, but we cannot because we don't have this generically liberal model.

Paavo Monkkonen 50:19

Yeah. So one thing I was wondering is, you know, I guess Zurich has a lot of co-ops compared to other cities in Switzerland. So I wonder if, you know, you looked at the differential tenure of the new construction, if it was not just like traditional rental Swiss style or co-ops, which may be a little different. I don't know if you can give your thoughts on that, how that might matter.

Elena Lutz 50:39

I mean, so that's a great point. So cooperatives in Switzerland have an important role in providing affordable housing. However, we consciously left these out of the study because first of all, we couldn't get rental data on them, right? We kind of wanted to restrict ourselves to, first of all, the data that was there, which is more focused on market rate. And also then maybe if it's a very different logic of how you set your price because you're a cooperative, it's maybe not so comparable. So then in the end, we decided to just focus on everything that's market rent, which is still really the vast majority of housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 51:14

Right. Can you give us a sense of the typical building that's built in these up-zoned areas? It's 20 units, one owner that rents them all out or how does it work? So, a typical building that would be built usually is one owner that rents all the units out.

Elena Lutz 51:24