Episode 82: Lessons From the UK Housing Shortage with Anthony Breach

Episode Summary: What happens to housing quality and affordability when any proposed development can be vetoed? Can the public sector reliably deliver most of the housing that people need? If it can, should it? Ant Breach shares insights from the Centre for Cities’ report on the United Kingdom’s homebuilding crisis.

Show notes:

- Watling, S., & Breach, A. (2023). The housebuilding crisis: The UK’s 4 million missing homes. Center for Cities.

- Watling, S. (2023). Why Britain doesn’t build. Works In Progress.

- Episode 59 of UCLA Housing Voice with Paavo and Mike M., on the costs of discretionary housing approvals.

- “Housing outcomes in the UK improved considerably over the course of the 20th century. Space per person and the quality of stock both rose as incomes increased, transport technology enabled longer commutes from cheaper land, and demographic change caused households to shrink. How people lived changed too. At the start of the 20th century, 90 per cent of people were private renters. After the end of the post-war period in 1981, only 11 per cent of people were private renters, 57 per cent were homeowners, and a third of people were in social housing.”

- “Today though, there is a severe housing crisis in Britain, especially in the most prosperous places in the Greater South East. Across England, the average house costs more than ten times the average salary, vacancy rates are below 1 per cent, and space per person for private renters dropped from 34m2 in 1996 to 29m2 in 2018, and from 31m2 to 25m2 in London. There is a consensus that Britain has a housing crisis due to a shortage of new homes. The current government has a notional aspiration to address this by enabling 300,000 homes a year in England but has struggled to achieve more than 240,000 since 2018 – itself the highest rate of construction since the Financial Crisis in 2008.”

- “Much of this is well-known. There are though two competing explanations for the housing shortage:

- The discretionary planning system established by the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, which is argued to have introduced an unpredictable case-by-case decision-making process that has reduced development.

- The decline of Postwar Britain’s extensive council housebuilding programme from the 1980s. From 1945, councils built roughly half of all new homes until the introduction of Right to Buy for council tenants in 1980. As private housebuilding did not increase after 1980, it is argued recent lows in housebuilding are due to the lack of new council housing.”

- “Both accounts have some truth to them … However, the two explanations do differ on the root cause of the housing shortage and on priorities for reform. The core of the disagreement is whether planning reform or policy to encourage a resurgence in council housebuilding will provide the bigger and more permanent increase to housebuilding required to end modern Britain’s housing crisis.”

- “As both the planning system and mass council housebuilding were introduced shortly after the Second World War, and the former persisted after Right to Buy in 1980, these competing accounts can be investigated by comparing housing in Britain in the post-war period of 1947 to 1979 to other periods and to other Western European countries. To determine whether the planning system is the primary cause of the housing crisis, we test the first two hypotheses of the report:

- Hypothesis 1: English and Welsh housebuilding rates began to decline after 1947, not 1980.

- Hypothesis 2: British housebuilding rates and housing outcomes of the post-war period between 1947 and 1980 were worse than those of similar European countries.”

- “If the two hypotheses are tested and the deficit in total housebuilding begins during the post-war period between 1947 and 1979, then one potential response could be that Postwar Britain failed to build enough council housing. To test this response, a third and a fourth hypothesis on post-war housing emerge:

- Hypothesis 3: The rate of British council housebuilding in Postwar Britain did not fall below public housebuilding in other countries pursuing mixed-tenure strategies.

- Hypothesis 4: The private sector housebuilding rate did not increase as policy shifted towards private ownership towards the end of the post-war period.”

- “Using data from the United Nations, it is now possible to compare the outcomes of British housing policy from 1948 through to 2000 against twelve other Western European countries and test the four hypotheses.”

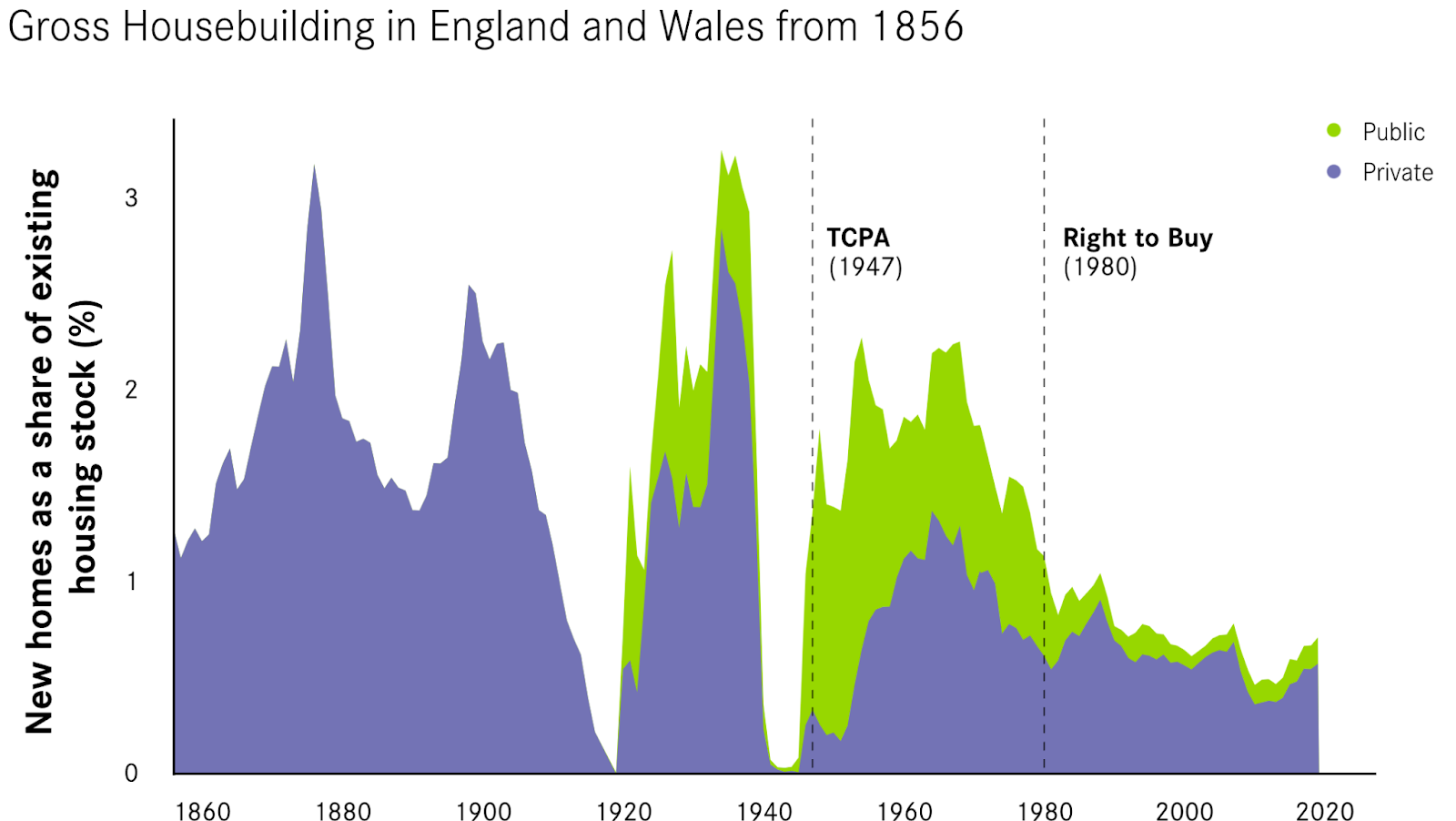

- “Gross housebuilding rates, separated into building by private and public tenure, are shown in Figure 1 and indicate that housebuilding in England and Wales fell from an average of 1.9 per cent growth per year between 1856 and 1939 to 1.2 per cent between 1947 and 2019 – a fall of over a third. Even though public sector housebuilding increased from 0.2 per cent a year before 1939 to 0.5 per cent after 1947, annual private housebuilding fell by more than half, from an average of 1.7 per cent before 1939 to 0.7 per cent after 1947. English and Welsh housebuilding never recovered to its pre-war levels.”

- “There are three further conclusions to draw from the decline of housebuilding set out in Figure 1.

- First, the decline in housebuilding happens immediately after 1947. England and Wales reached its highest ever period of housebuilding in the interwar era between 1920 and 1939 with an average annual growth of 2.3 per cent, compared to an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent between 1947 and 1979. No peak year for housebuilding after 1947 exceeds the four peaks in the interwar or Victorian periods.

- Second, as the chart displays England and Wales’s gross housebuilding rate, it overstates the net number of new dwellings added in the post-war period between 1947 and 1979 due to the high rate of demolitions in the 1960s.

- Third, the English and Welsh housebuilding rate declines further during the 1970s. Annual housebuilding rates in England and Wales fell from 2.3 per cent in 1968 to 1.2 per cent in 1979, before 1980 and Right to Buy. The decline affects not just public (mostly council) housebuilding but also private housebuilding, which fell from 1.2 per cent to 0.7 per cent over the same time frame.”

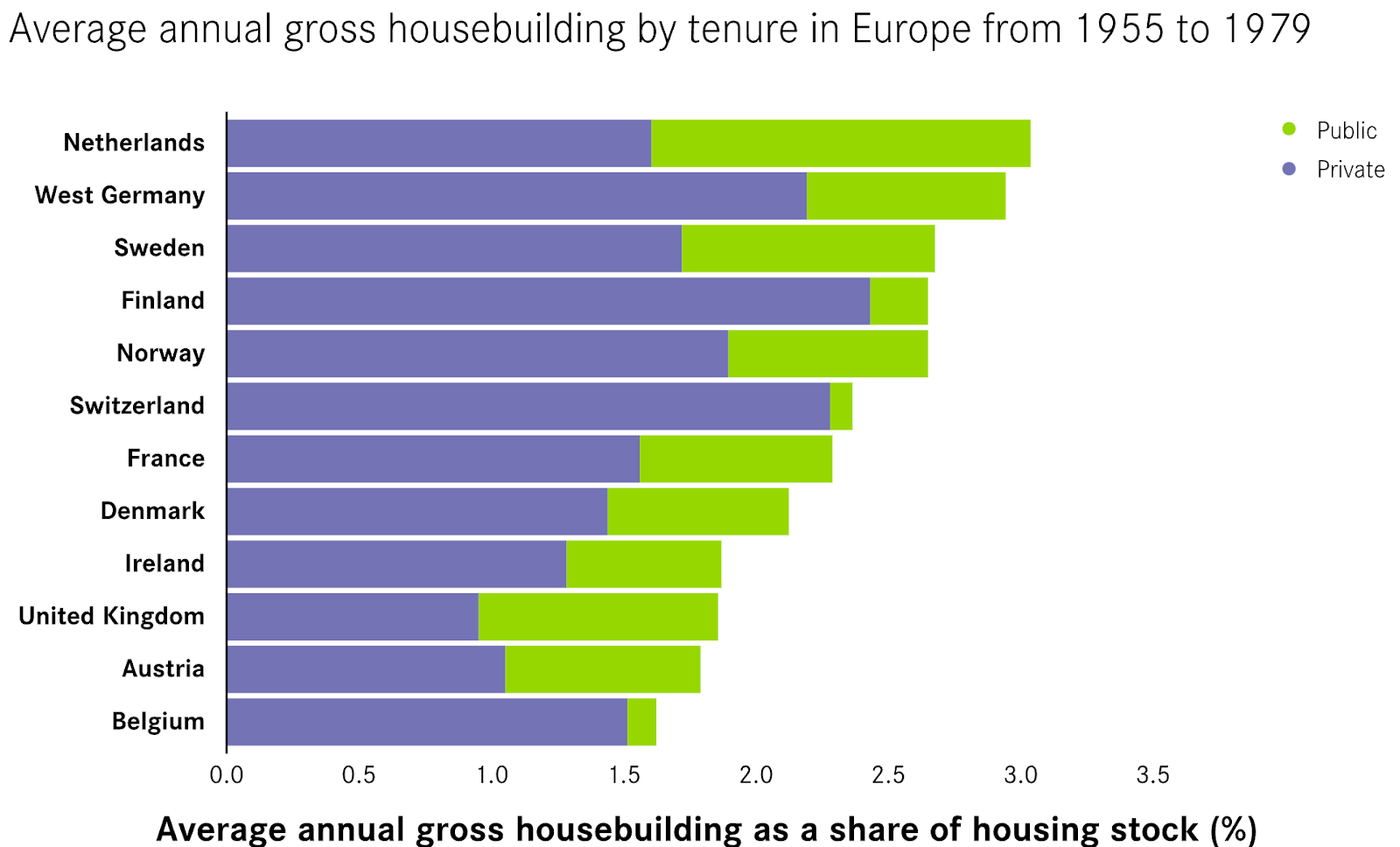

- “Figure 2 shows the average annual gross housebuilding rates from 1955 to 1979 for twelve Western European countries divided by tenure. The UK ranks towards the bottom of this list, seeing only 1.9 per cent growth in the number of homes every year, much less than France with 2.3 per cent annual growth in housing stock, and West Germany and the Netherlands on 3 per cent growth in housing stock every year … Differences in war damage seem not to explain this – Ireland, Switzerland, and Sweden built more than the UK despite being neutral in the Second World War.”

- “Postwar Britain had a low rate of total housebuilding. Although the UK had a public sector housebuilding rate slightly above average for countries with significant public housing programmes,9 it had the lowest rate of private housebuilding in the post-war period of any Western European country.”

- “A low rate of private housebuilding was not necessary to enable a large public housebuilding programme. To take two examples, from 1955 to 1979 both the Netherlands and Sweden had a higher total housebuilding rate than the UK. Their housebuilding rates by tenure and year that were in surplus of the UK can be seen in Figure 3. The Netherlands and Sweden built more private sector housing than the UK in almost every year from 1955-1979, and also had long periods in which they built more public sector housing than the UK … Even though the Netherlands and Sweden had a smaller role for the public sector as a share of their tenure mix, both had higher average rates of public sector housebuilding at 1.4 per cent and 0.96 per cent respectively than the UK’s average rate of 0.9 per cent per year.”

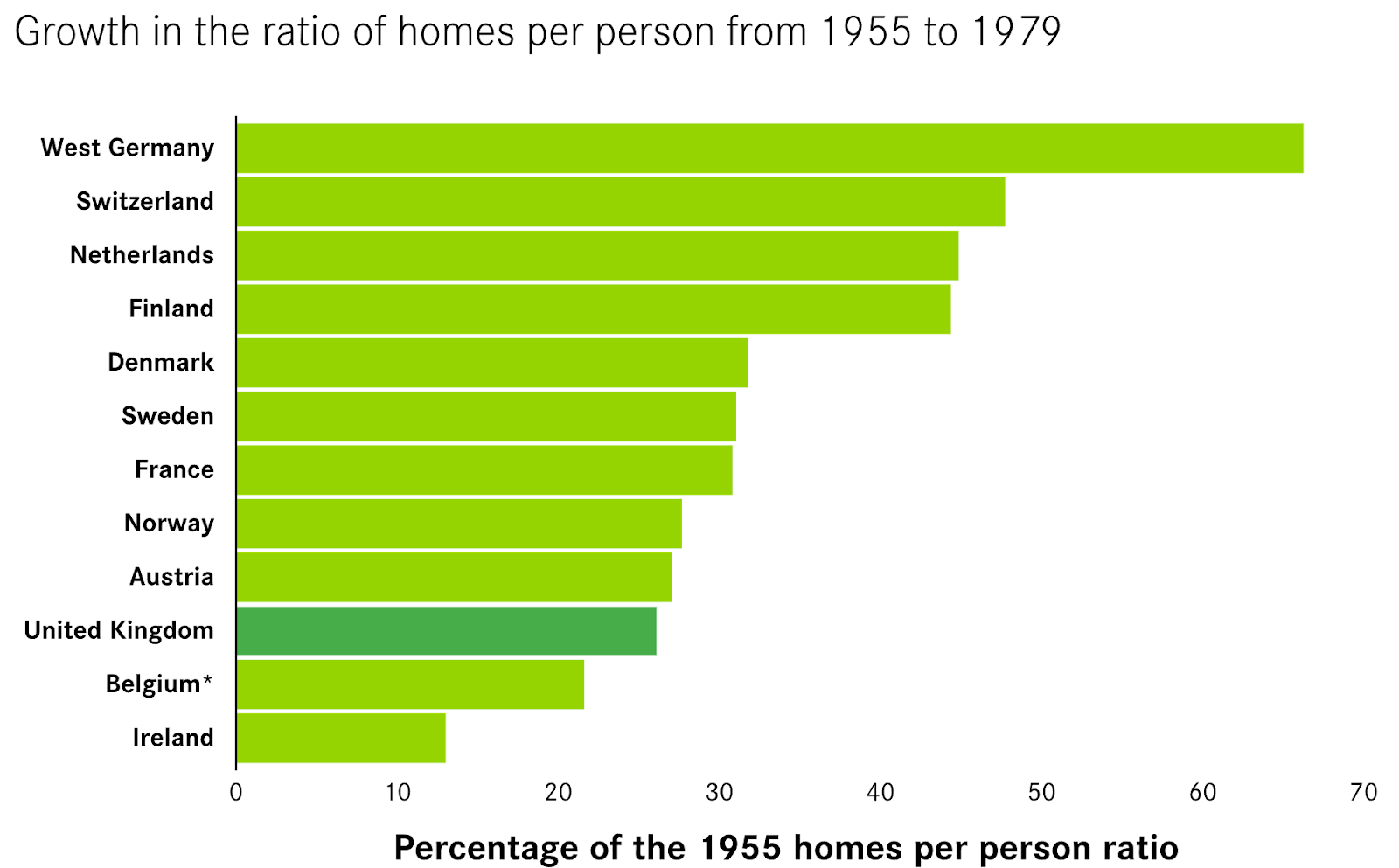

- “As Figure 4 shows, even after accounting for population growth and any impact from demolitions, the UK had one of the lowest increases in net housing supply in Western Europe from 1955-1979. For example, while the UK increased the number of homes available per person by 26 per cent, Switzerland managed an increase of nearly double this, at 48 per cent.”

- “The result of British underbuilding during the post-war period was that the UK lost its initial head-start in housing outcomes. Although the UK’s number of homes per person was 5.5 per cent above the average Western European country in 1955, it had fallen to 1.8 per cent below the European average by 1979.”

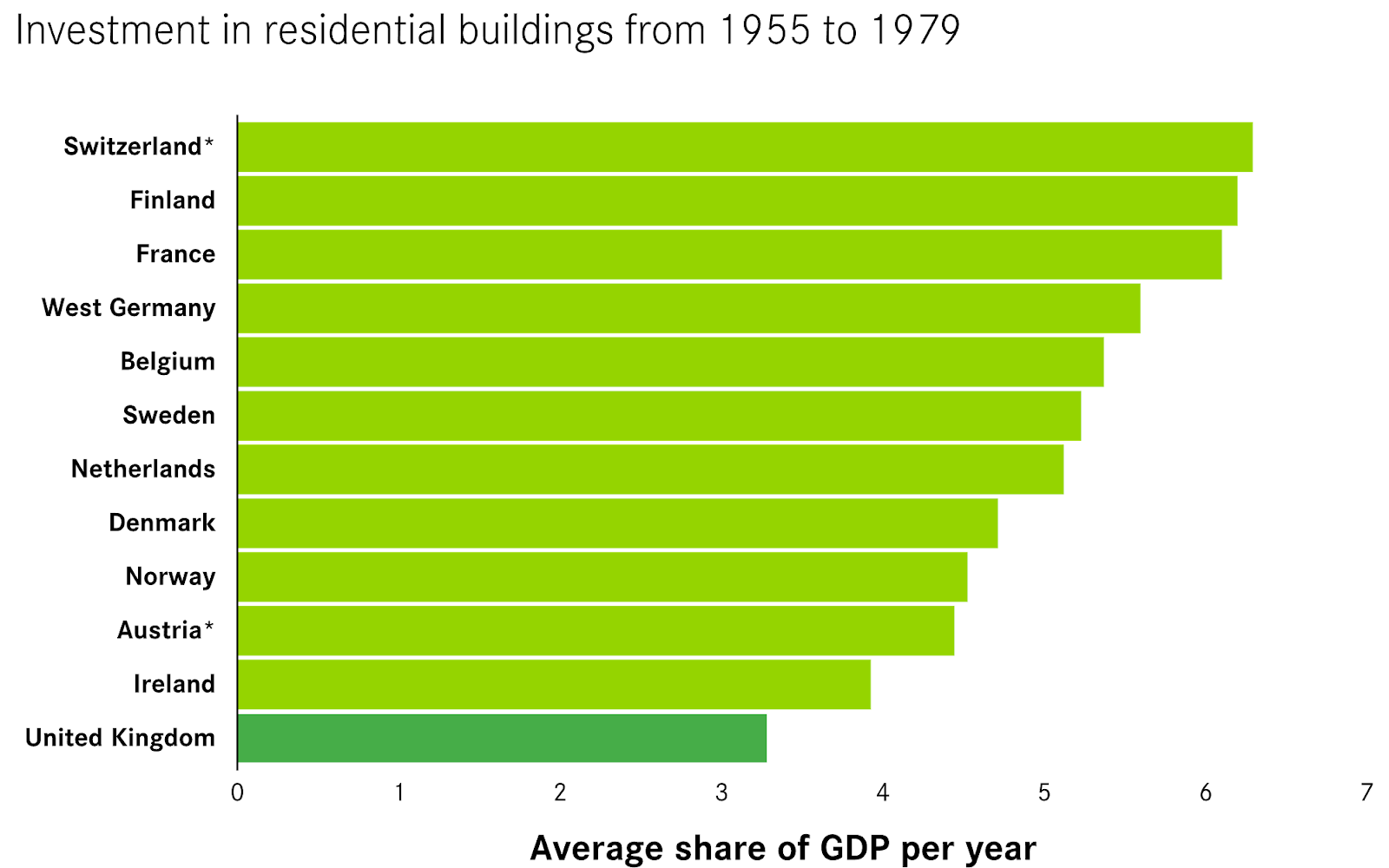

- “Another argument might be that Postwar Britain’s poor housebuilding performance can be explained by a choice of “quality over quantity” … if Postwar Britain had prioritised fewer but higher quality dwellings, then we should expect to see an average rate of investment in residential construction and larger dwellings than other European countries. However, Figure 6 shows that the UK invested the least in housebuilding of any Western European nation as a share of GDP – only an average of 3.3 per cent of GDP per year, compared to 5.1 per cent in the Netherlands and 6.2 per cent in Finland … In addition, Table 1 shows that by 1992, average UK housing size by floor area was significantly lower than its peer countries in Western Europe.”

- “The quality of new stock also declined as the post-war era progressed, with a trend towards smaller properties and plots, using inferior materials and the removal of white goods from developer ‘bundles’ for new homeowners. Furthermore, new homes were in worse locations than existing stock, as the rapid expansion of green belts after 1955 meant that new houses on greenfield land were built further away from urban areas, with worse access to jobs and longer commutes than had pre-war trends continued.”

- “European central and local governments in the post-war period all provided some subsidy for housebuilding programmes. These “bricks and mortar” subsidies were designed to mitigate the negative effects of demand-side rent controls that had emerged during the World Wars in every European country – including the UK – in both the public and private housing sectors. Bricks and mortar supply-side grants and subsidised low-interest rate loans that subsidised private housebuilding for homeownership or private rent were implemented in every European country after the Second World War – except the United Kingdom.”

- “The supply of new council homes fell in the 1970s, with the council housebuilding rate declining from 1.1 per cent growth a year in 1968 to 0.6 per cent in 1979. This decline is part of why the total rate of housebuilding fell towards the end of the post-war period … Alongside the UK, the other European countries that relied on a substantial mix of private and public sectors and centralised social housing subsidies to deliver high levels of housebuilding after the Second World War included Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands … Every European country with a large public housebuilding programme saw it decline rapidly after the early 1970s, for most countries roughly in time with the withdrawal of centralised subsidies as pressure on public budgets and growth deepened across the developed world after the Oil Shock in 1973.”

- “Although it did not exceed pre-war housebuilding rates, the early 1950s saw the peak housebuilding rate of Postwar Britain, driven by both this high council housebuilding and planning reforms to the 1947 regime that reduced local authority land development charges and consequentially caused private housebuilding to increase. This level of public housebuilding was not sustained, and Britain converged to a level typical of other European countries that pursued mixed-tenure strategies by 1957.”

- “Private housing did receive more policy support on the demand-side as the postwar period progressed. After 1963, various tax reforms (including the abolition of Schedule A taxation in 1963, followed by the exemption on domestic properties from Capital Gains Tax in 1965 and the new option mortgage subsidy in 1966) introduced demand-side subsidies for homeownership. Despite the policy shift to support private housing in the mid-1960s, Table 2 shows that UK private housebuilding actually fell from its peak in 1964.”

- “Postwar Britain never had a single year of private housebuilding as high as the average private building rate of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, or Sweden. Where Britain was atypical is not just that private sector housebuilding was low on average – it also fell further from an unusually low base. This resulted in private housebuilding peaking, averaging, and falling to a lower level than in any other European country by 1979.”

- “House prices also grew faster than construction costs over this period, and land became much more expensive as a share of total build costs. The price of land increased from approximately 10 per cent of the average suburban house price in England in 1960 to 25 per cent in 1970, and one third of the average price in outer London and the Home Counties. This indicates that the supply of new dwellings in the post-war period was constrained primarily by the availability of land on which it was lawful to build homes – in other words, with planning permission.”

- “The planning system established in England by the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 is marked by internationally unusual discretion and restrictions on development. In effect, while most other land-use regimes abroad are typically rules-based ‘zoning’ systems, in England and other systems strongly influenced by TCPA 1947 (the devolved nations, Ireland etc.) the permission-and-appeal regime induces case-by-case decision-making, despite being nominally ‘plan-led’. In short, this means that instead of the planning system allowing all development that follows the rules, in England it is possible for developers to follow the local plan and still have their application rejected. This rejection can be delivered by local authority planning officers, the local councillors who sit on the local authority’s planning committee, central government’s planning inspectors, or even the Secretary of State. The effect is that instead of all land being available for development unless it is prohibited, development is prohibited on all land unless a site is granted a permit (planning permission).”

- “Other European countries did not make the same choices as Britain did in the post-war era. Planning and housebuilding regimes did vary considerably across Western Europe after the Second World War, but European countries with more successful housing outcomes differed from the UK in three ways:

- Their governments had greater central power over local planning authorities and could re-draw local development plans that were unable to meet housing requirements more easily.

- Their planning systems had less of a discretionary element. In contrast to the UK, in most European countries planning permission was and is automatically given by an administrative body if it complies with the plan. This meant that there have been fewer opportunities for European local authorities to obstruct development.

- Their systems of national development control were instituted later than the UK did in 1947. Germany enacted its planning law in 1960, the Netherlands in 1965, and France in 1967. These systems had fewer restrictions on development than England’s, but they also had a longer period after the Second World War in which restrictions were minimal.”

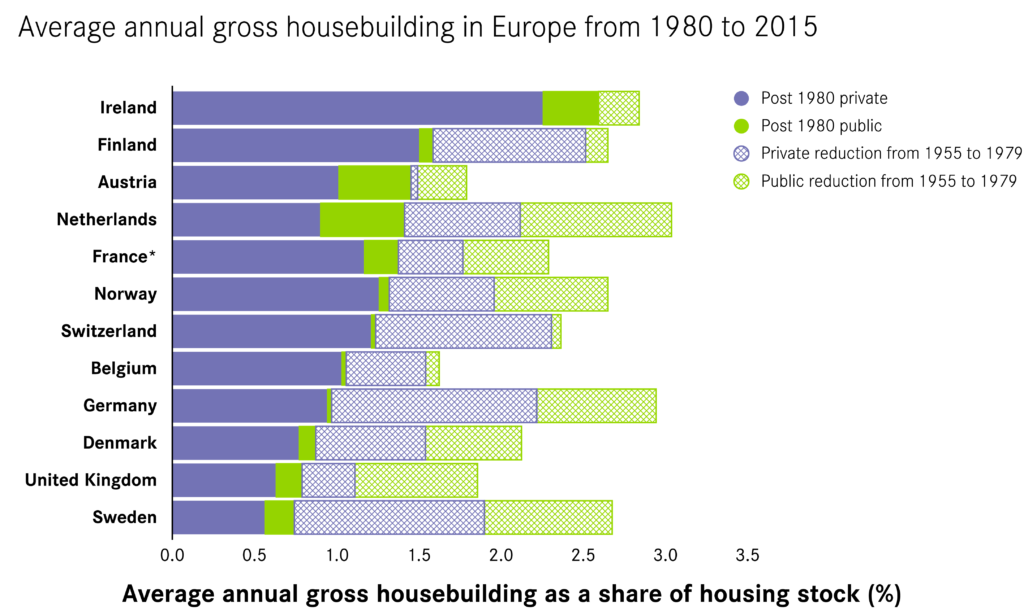

- “Figure 10 shows total housebuilding in Europe from 1980 to 2015, divided by tenure and showing reductions in housebuilding rates from the 1955 to 1979 period in hashed bars. There are three lessons in European housebuilding after 1980 to compare to the earlier trends of post-war housebuilding rates in Figure 2.”

- “First, total housebuilding after 1980 was lower than post-war rates in almost every country. The exception to this is Ireland, which is discussed in Box 7. Second, the public housebuilding rate declined in every country in Europe.”

- “Third, Britain remains at the bottom of the table. The average annual total housebuilding rate in the UK fell from 1.9 per cent between 1948 to 1979 to 0.8 between 1980 and 2019. In part, this was due to the end of mass council housebuilding after the introduction of Right to Buy – the public housebuilding rate (including housing associations), fell in the UK from an average of 0.8 per cent growth per year in the 1970s to 0.3 per cent in the 1980s and 0.1 per cent in the 2000s. However, it was also due to the fact private housebuilding fell, decreasing from 0.8 per cent to 0.7 per cent and finally to 0.6 per cent annual growth over the same period.”

- “European housing outcomes since 1980 have become more varied relative to the UK as housebuilding rates have changed. Figure 12 shows that some European countries, including Finland, Switzerland, and France, continued to expand their advantage in the number of houses per person relative to the UK that they were showing in the post-war period in Figure 5, but others are not. Finland’s performance is particularly impressive, with the number of homes per person increasing from 86 per cent of the British ratio in 1955, to roughly matching it in 1980, and then reaching 123 per cent of it in 2015.”

- “Had the UK built houses at the rate of the average Western European country from 1955 to 2015, it would have added a further 4.3 million homes than it actually did – resulting in 15 per cent more homes than the 28.3 million dwellings that actually did exist in 2015. As the UK increased the size of its housing stock by 12.2 million homes from 1955 to 2015, these 4.3 million extra homes would have required new additions to be 35 per cent higher across the entire period.”

- “Table 3 shows that had the UK adopted a policy approach similar to the average European country, it would have built 4.3 million more homes from 1955 to 2015 to keep up with European housing outcomes. As amounts to 5.9 million more homes built by the private sector, and 1.6 million fewer homes built by the public sector. Accordingly, the tenure mix of new supply would have changed from 64:36 private:public to 80:20. As the most important factor behind the UK’s unbuilt backlog is a low rate of private housebuilding, every single modelled scenario sees the private sector build more houses. However, there are a few countries that indicate the UK could have built more private and more social housing. Had the UK taken the policy approach of the Netherlands or Austria, the British public sector would have built between 2 to 2.2 million social homes beyond our actual social housing programme, alongside an additional 2.8 to 7 million new private sector homes.”

- “Ending the housing crisis in the next twenty-five years would require England to add 442,000 homes every year, double the current housebuilding rate of 220,000 a year, as shown in Table 4. Solving it in ten years, or two parliamentary terms, would require 654,000 new homes a year in England. Achieving housing outcomes of countries with above-average records, such as Finland and Austria, would require even higher amounts of housebuilding over the same periods.”

- “Britain has not allocated enough land for development for decades … Despite Britain’s successes in public housebuilding, other European countries, like the Netherlands and Austria, show that alternative approaches could have provided more social housing and achieved better outcomes … The root cause of the housing crisis is the decline in the supply of land, not the decline in subsidy. Whatever choices the UK makes about housing tenure and whichever countries it learns lessons from, allowing more development on more land is the only way the housing shortage will end.”

- “Housing targets have once again become a divisive issue in Parliament, and expectations that the Government can now fulfil its ambition to build 300,000 homes every year in England are now low. Yet even building 300,000 homes a year – a housebuilding rate of just over 1 per cent growth a year in England – would take more than half a century to reach European average housing outcomes. England needs a higher target to end the housing crisis in the foreseeable future … New social and council housing can be part of the solution, but achieving a large increase in the number of new homes built every year is more important than a small improvement in the distribution of an insufficient number of new homes.”

- “The scale of the housing challenge means that tinkering with little reforms will make little difference to housing conditions and the British economy. A big problem requires a big reform. Fixing the design of the planning system, fundamentally untouched since 1947, is that big reform. As a long-term goal, replacing the current Town and Country 1947 planning system of England (and the devolved nations) with a new flexible zoning system would increase housebuilding and end the housing shortage, if it had the following features:

- A flexible zoning code designed by national and devolved governments for local governments to use in local plans, with a small number of different mixed-use zones corresponding to different types of neighbourhood.

- Rules stating that planning proposals which comply with a zone-based local plan and building regulations must be granted planning permission.

- Local Plans and Local Transport Plans – which are currently different documents – should be merged into the same document, so that planning for development requires planning for infrastructure and vice versa.

- Better organised and frontloaded public consultation in the creation of the local plan, rather than individual proposals.

- Phasing of non-developed land into zoned areas, depending on local population growth, affordability, and vacancy rates.

- Zoning of land in walkable distances around train stations in the green belt for suburban living and with protected green space, which would provide 1.8 to 2.1 million homes.

- Replacing negotiated ‘developer contributions’ towards local government with a flat levy on a development’s value for infrastructure and new social housing.

- Maintaining opt outs and special designations where case-by-case decisions continue, such as conservation areas, listed buildings, national parks, and wildlife reserves to protect environmentally or architecturally precious land.

- Creating ‘safety-valves’ in the system that allow alternative pathways for development, such as the Street Votes or Builder’s Remedy proposals.”

Shane Phillips 0:05

Hello, this is the UCLA Housing Voice podcast, and I'm your host, Shane Phillips. This week, we're joined by Anthony Breach, or Ant, to talk about the housing crisis in the United Kingdom. More specifically, we talk about the home building crisis that's been brewing there for several generations and has yielded the UK a mix of very low quality homes with some of the highest housing prices on the planet.

There were a few topics we were particularly interested in speaking with Ant about. One was the UK's approach to planning and approving housing, which is entirely discretionary. We talk about how that system came into being and what the future might hold. As Ant puts it, for all the shortcomings of American-style zoning, adopting it in the UK would actually be a huge improvement over their status quo.

We also were intrigued by the history of public housing in the UK, where about half of the homes constructed from the 1950s to 1980 were publicly built, what they call council housing. That's a higher share than any other European countries in their study over that period, but unlike those other countries, Britain complemented this surge of public home building with sharp restrictions on private development. It fell behind its peers on a variety of housing outcomes, and in the 1980s and 90s, when support for public housing declined across the Western world, the UK didn't really have a market in place to fill that gap, and affordability kept declining too.

Our last episode was about the impressive reforms undertaken by New Zealand in recent years, sort of a vision of hope in the English-speaking world. This time, it's more of a vision of despair and a cautionary tale. At the same time, the UK is also now showing signs of hope and necessary urgency, and their experience is definitely one worth learning from.

The Housing Voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies with production support from Claudia Bustamante and Irene Marie Cruise. As always, send your questions and feedback to shanephillips@ucla.edu. And with that, let's get to our conversation with Ant Breach.

Anthony Breach is Associate Director on the Research Team at Center for Cities, a think tank dedicated to improving the economies of the UK's largest cities and towns. And he's joining us to talk about the Center's work examining the origins of Britain's housing shortage, some of the policies that both caused and sustained it, and what they should do to fix it. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are a bunch of parallels between the challenges in the UK and those in North America, and many of the causes and solutions are quite similar as well. Chalk it up to the special relationship between the two countries that we're always hearing about. Ant, thanks for joining us, and welcome to the Housing Voice Podcast.

Anthony Breach 3:05

Thanks, Shane. It's amazing to be on.

Shane Phillips 3:06

And my co-host today is Mike Lens, former Londoner. Hey, Mike.

Michael Lens 3:11

Hey, Shane. Welcome to Ant. Very excited to learn more about the UK housing situation, particularly things that I didn't learn when I was in London.

Shane Phillips 3:21

All right. So Ant, we start by asking our guests to give us a tour of a city that they know well and want to share with our audience. So where are you taking us?

Anthony Breach 3:28

Yeah, sure thing. So I think I'm going to take you guys today to Manchester. So it's a big city in the north of England. It's the biggest city in the north, and I think nowhere else on earth really signifies either the global urban renaissance better than Manchester, or indeed the failures of British urban policy over the past 100 years. So I think taking you really back in time to the emergence of Manchester as a major city, Manchester is the heart of the British Industrial Revolution. It's the cradle of the modern world that we now all live in. In Victorian times, that's the centre of Britain's century of dominance in the manufacture of textiles, with ships coming up the canal to Salford to bring cotton and then export cheap clothing all over the world.

However, in the 20th century, Manchester really begins to struggle. There was some adaptation to light engineering before the Second World War, but the collapse of the textiles industry really hits the city hard. Combined with anti-urban policy from the British government, which I think we might get into a little bit in this conversation, unemployment really explodes in the 1970s and 1980s. And from that basis, the city's leadership really realizes they have to get private investments into the city, partly to help the existing residents, but it's also so that the country's second largest city can play the role that it should be playing in the national economy.

And you can really see this in the city's built form. So if you go to the city centre, you can see this grand legacy of Victorian architecture in the city centre, these grand buildings with all this ornamentation, this very classical red brick. But until the 1960s, most of the suburbs would have been these traditional small terraced townhouses for the working classes, what we call two ups, two downs. So two houses, two rooms on the top floor, and two rooms on the bottom floor. Much of these back in the 60s and 70s would have been slums. So without an indoor toilet, without indoor piping, with a tin bath hanging on the wall. And although there's still some of this building stock that's been left and repaired and fixed up over time, whole neighbourhoods of this were just demolished and swept away in the 1960s and 70s by slum clearances, by our version of urban renewal. And that really just means as the economy is hitting rock bottom, the actual physical landscape of the city is also a wasteland in many respects.

But since the 1980s and 1990s, there's been a huge change in the built environments of Manchester with a massive shift towards high rises, particularly in the city centre. So back in maybe 1990, there were about 500 people living in the city centre. Today about 30 years later—

Michael Lens 5:49

That's small number. It's a lonely crew.

Anthony Breach 5:54

So 500, that's mostly like pub landlords, a few students, a very, very small number of people. 30 years later, that's now about 70,000 people. So a massive increase in the total in the population that has been brought about by huge urban change, by change in the physical built form. So there has been this huge renaissance in Manchester as it's trying to make up for lost time.

Michael Lens 6:15

Cool. And you know what I think a lot of people are wondering right now is if you are in Manchester on a Saturday, are you heading to the Etihad or are you more likely to go to Old Trafford?

Anthony Breach 6:30

Oh, so I'm from Liverpool.

Michael Lens 6:32

Oh, so screw them both.

Anthony Breach 6:35

Completely forbidden, right? I'm a different type of red or blue, right? You know, those guys over there, from Liverpool people call people Manchester wolves because they make textiles, right? Yes. So it's a completely different partisan petty divide. Yes.

Michael Lens 6:51

So Everton or Liverpool for you?

Anthony Breach 6:54

Maybe just about Liverpool for me. I mean, I originally grew up in Belfast and I moved to Liverpool as a kid. So you know, everyone else was already miles ahead and deep in these, you know, ancestral grudges.

Michael Lens 7:08

Well, you had your own ancestral grudges, perhaps.

Anthony Breach 7:10

Exactly. You know, I was on a higher level. So you know, the Liverpool kind of football thing is for me as well has always been a bit, you know, not quite severe as it is for some people.

Michael Lens 7:22

Okay, fair.

Shane Phillips 7:24

I do love a very subtle insult like wolves where you would never even know it's an insult if you weren't a local and someone didn't tell you.

Michael Lens 7:31

Like 200,000 people are enraged by that, but nobody else has a clue.

Anthony Breach 7:38

Yeah, exactly. Yeah. I mean, you know, that whole part of the world is, you know, people can tell exactly what town you're from depending on very slight changes in your accent and people know, they remember.

Shane Phillips 7:50

All right, so our conversation today is going to focus on a report that Ant worked on with Samuel Watling that was published in early 2023 titled The House Building Crisis, the UK's 4 Million Missing Homes. In that report, Ant and Sam make the case that, you guessed it, the UK has a shortage of 4 million homes. And they show through a bunch of housing data on the UK and by comparing it to data on other Western European countries that this shortage has roots that go back much further than many people believe.

In the US, the origin of our housing affordability problems is sometimes identified as around Ronald Reagan's presidential administration in the 1980s and particularly the huge budget cuts he made to the Department of Housing and Urban Development at that time. Something similar happens in the UK. Just replace Reagan with Margaret Thatcher and replace HUD's budget cuts with the Right to Buy program, which sold off a lot of the nation's public housing. In both countries, there is some real truth to these arguments, to the blame ascribed to these parties, but it's also an oversimplification that lets a lot of other guilty parties off the hook and it ignores policy and political changes that got their start much, much earlier.

In Britain, Ant and Sam make the case that the shortage can be traced back to the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, which is linked to a strong shift to discretionary rather than plan or zone-based planning, and the decision to increase public sector home building at the expense of private sector home building rather than as a complement to it. We've discussed the Lewis Center's research on discretionary housing approvals on this podcast and Britain arguably has the most discretionary housing approvals process in the world, or at least among the world's wealthier countries. I'm actually curious whether you think it is in the world or just among the wealthier countries, Ant, but this is a topic we've wanted to cover for quite a while.

So Ant, to start us off, just paint us a picture of the UK's housing conditions relative to other Western European countries right around the time of the Second World War, and then how things looked jumping forward several decades to around 1980, just as the Thatcher administration was getting started. I think you lay out pretty clearly that the UK started out as one of the better performers in the pre-war period and then ended the 70s as one of the worst. Is that correct?

Anthony Breach 10:12

Yeah, that's right. So obviously right at the end of the Second World War was better than quite a few Western European countries due to extensive damage from the Second World War across Europe. The UK does have a little bit of bomb damage as a result of the Blitz in its big urban areas, but on the whole, we leave World War II with some of the best housing outcomes, if not the best housing outcomes in Europe, mostly because we have a really excellent 1920s and 1930s where we build a lot of housing over that period. So it's quite an interesting difference between any kind of cultural memory between the UK and the US in that while the United States has an amazing 1920s and a terrible 1930s with the Great Depression, in the UK it's the opposite. So our 1920s are pretty grim. We have very severe unemployment problems throughout all of that period. We have a much stronger recovery from the Great Depression. We recover faster, more profoundly, and a huge part of that is housing. So the economic historian Nick Crafts calculated that about a third of Britain's recovery from the Great Depression is caused by a massive house building boom, like the biggest double house building that the country has ever seen in the 1930s, that results in the expansion of massive suburbs around our growing big cities, so primarily London and also Birmingham at this time. I think by the end of the 1930s, something like a third of all buildings in Birmingham are less than 20 years old. It's just a massive expansion in the housing stock. This is all the kind of classical English suburbs that you've probably seen on like chocolate boxes and similar over this period, sort of a nice classic, maybe semi-detached or townhouse, big garden, handsome kind of arts and crafts, fake Tudor kind of architecture. We're really seen as a world leader in terms of design and architectural outcomes at that particular point in time. All those things, we've got all those advantages kind of heading into the war and we leave the wartime with those advantages as well, which means that by 1955 or so, so a little bit after the actors passed, we probably have about 5% more homes per person than the average Western European country. There's a load of countries, some of whom are already much poorer than us, but that have less, but also some that have experienced severe bomb damage and war damage that have less in us as well. Right. And I do want to highlight that point that this is not just comparing the UK to West Germany that's actually comparing to other countries that were neutral in World War II and really had very little damage at all, if any. Yes, that's right. So places like Switzerland and Sweden, obviously very affluent societies, they have relatively good housing outcomes by Western European standards. On the other hand, we also have Ireland, which is exceptionally poor by Western European standards throughout this period. Also neutral. They have far fewer houses than we do throughout this period. So if we've got that kind of 5% advantage at the start of the post-war period in 1955, actually by the end of that period, by 1979, that's fallen to a 2% deficit. So even though we're building lots of houses over that period, there is construction happening, there is a house building program, which we'll get into. In relative terms, we're slipping down the rankings. And this kind of mirrors what we see in other parts of the British economy in terms of exports, in terms of productivity, in terms of wages. You're seeing improvements in absolute terms, but actually relative decline compared to other Western European countries.

Michael Lens 13:34

And the contrast with the United States at this time is also fairly clear, at least to me, this is the really big moment of housing expansion in our country in that post-war period that gets a lot of credit for some of our affluence in the middle to late period of the 20th century.

Anthony Breach 13:54

Yeah, exactly. And one way you can think about it is in the 1930s, we have incomes are rising, right? We do have this massive boom in house building in the UK. Incomes rise even faster in the post-war period, absolutely unprecedented level of income growth. But house building is still lower than during the Great Depression. So even though, again, you are seeing that improvement, in the background, there's already this silhouette of a problem that's starting to emerge. A few people back then were starting to sound the alarm, even though it wasn't initially obvious.

Michael Lens 14:25

Yeah.

Shane Phillips 14:27

So you show that the quantity and quality of home building in these various other countries and the poor performance of the UK in particular played a big role in its relative decline. So give us some of the data on how home building in the UK compared to other European countries in that post-war period between the end of World War II and around 1980.

Anthony Breach 14:48

Yeah. So in terms of the different patterns between countries, there's definitely a difference between those countries that are recovering from war damage and then those countries that are more neutral in places like Switzerland and Sweden. You see by the mid-1960s or so, West Germany is going absolutely gangbusters on building new houses, right? They absolutely have to. They've got a very, very severe housing shortage as a result of the war. But by the middle of the 1960s, it seems to basically be complete. House building growth really slows compared to its early post-war period average. But it's still outpacing the UK, right? They then kind of go from being way behind the UK to significantly overtaking the UK in terms of homes per person over that period. You see places like Denmark and Sweden, again, didn't really have a significant war damage in that period. They have an advantage over the UK initially. They pull further away as a result of that pattern. Then places like the Netherlands and Finland, which are kind of poorer or more damaged, really catch up with the UK over this period. So it's every front, really, you see these big changes.

Shane Phillips 15:50

And just in terms of ranking here, the UK is essentially right near the bottom throughout this period. I'm sure there's ups and downs over that time. But averaging it all out, it really built less than I think there's one or two other countries in the dozen or so you looked at that built a little less than it did, but others that were building 50%, 100% more on average.

Anthony Breach 16:12

No, yeah, absolutely. So the reason why so many countries overtake or catch up with the UK over this period is we just build far less. So although you've got countries like Finland or Sweden really leading the pack at the top, actually across this whole list of Western European countries we compare against, so places like France, the Netherlands, Finland, Switzerland, and similar islands as well, actually the only two countries that build less than us on average over this period are Austria and Belgium. And Austria has very low population growth over this period, there's really not very much demand for new housing at all. Belgium just seems to be a bit different across a variety of dimensions. So there's this quite clear link between very low house building and then quite poor housing outcomes and deterioration in these outcomes, even though this is during the period of what many people in the UK consider to be the golden age of house building in Britain.

Shane Phillips 16:50

And this is not really a focus of this report directly, but I feel like housing costs and affordability are a big motivation for the work you guys did here and an outcome you're obviously very concerned about. It is, of course, one of the biggest interests at the Lewis Center as well and on this show. So how has affordability in the UK been evolving compared to peer countries over this period? And you can even tell us a little bit about where things stand today, I know it is not a pretty picture.

Anthony Breach 17:33

Sure thing. So this is a tremendously difficult question to answer, it's why we don't really talk about prices in the report. You've got to think about exchange rates, incomes, rent controls, floor plate data all make it really difficult. We've made maybe two observations. One is that throughout most of this period, Britain has both very tight rent controls and also very tight mortgage controls. So the actual access for people to buy housing, to use demands, to access better housing is really quite limited. You see in the private rental market, the quality of rental housing is poor generally, but also as a result of these tight controls on finance, the quality of buildings for home ownership also tends to deteriorate over this period. And once these controls on mortgages are lifted in the 1980s or so, it's kind of Bank of England research which shows there's only three advanced economies in the world that have seen faster house price growth since 1980s, which are Australia, Norway and Spain. And that's sometimes taken to in the UK, oh, we've had out of control financialization, that's the real cause of the housing crisis. To me what it indicates is that we had suppressed demand for home ownership before the relaxation of those controls. And actually we've seen kind of a very rapid rise to an equilibrium level, even if that equilibrium is extremely unaffordable.

Shane Phillips 18:44

Right, because you didn't suddenly make mortgages much more favorable, lower interest, longer term than other peer countries. It was just you actually kind of came to their level and made it roughly as easy to acquire mortgage credit as these other places had done for decades.

Anthony Breach 19:00

Exactly. So a big theme of what I say to policymakers here is we don't have to be crazy radical, we don't have to be experimental, we just have to be normal. And that's difficult in British housing policy. But this is one area in which we went from being very restrictive to being normal, and we have this outsized effect because the rest of our system still is not normal. If you ask people who've moved from other developed countries to the UK, they'll typically be shocked at how bad the quality of housing is and how bad value it is compared to what it is in their own country. But it often comes to the thing that most shocked by is how everybody in Britain thinks it's normal to have terrible housing, right? You know, like, oh, you know, what do you mean? Of course, we've got damp, you know, all throughout our walls, you know, yeah, yeah, of course our landlord, you know, we're living in our early 30s sharing an old Victorian family house, five of us, you know, that's just, doesn't everybody do that? And, you know, the idea that that might not be normal anywhere else is very alien to British people.

Shane Phillips 19:54

Interesting. And how about just on the cost metric, however you want to measure that?

Anthony Breach 19:58

Yeah, sure thing. So I did some kind of initial scoping for this recently, so I can't remember the exact numbers off the top of my head, but essentially, depending on how you measure it, the average house price in the UK and the US seems to be pretty similar between the UK and the United States. But obviously, wages in the UK are about a third lower than they are in the United States. This is sort of the origin of this kind of idea that, you know, the UK essentially has California house prices, but Mississippi wages, right? Maybe the most easiest way to think about it that we have get very, very bad value for our money and for the amount of labor that we put in to kind of survive day to day, you know, because we have a relatively fixed amount of our income goes on housing, you know, wherever we are, we get very poor quality dwellings for what we get.

Shane Phillips 20:41

Yeah, a common measure of affordability here in the US, which is flawed in some ways because it doesn't take into account interest rate differences and that kind of thing. But it's just the ratio of median home value to median incomes. And you know, I've heard you say that in much of the UK, that ratio is around 15 to one, which is just that is right near the top of the world. There's a few places like Hong Kong that are significantly higher, but not many.

Mike Lens 21:10

Hong Kong has nothing to do with the UK, of course.

Anthony Breach 21:14

Yeah, maybe there's a connection there.

Shane Phillips 21:16 But here in the US, as bad as things are, even in places like LA, I just put together a list of the largest cities in the US and among the top hundred cities in terms of population, the highest ratio actually is 11.5 to one and it's Los Angeles, actually, where we have very high prices and actually quite low incomes relative to those prices. New York is about 10 to one. Chicago and Houston are four, four and a half to one. And so we're talking 50%, 100%, 103 times as bad in some cases in the UK compared to at least the more affordable parts of the US. Of course, I'm sure there are more affordable areas in the UK as well, though.

Anthony Breach 21:59

Well, that was kind of my first thought was that actually, I think the most shocking statistic there is what you just said about Chicago being four times the average incomes. That would be the very, very poorest place in the UK, would maybe be about four. So somewhere like Aberdeen, which has had a massive shock to its oil industry over the past five years or so, very, very severe unemployment problems, is about maybe high free. So very, very poor kind of former mining towns in Lancashire are maybe about four or five or so.

Michael Lens 22:27

Where the demand for housing has cratered. And that's what creates that kind of favorable in a way ratio.

Anthony Breach 22:33

The difference is, you know, this is a big difference in the US and the UK on this, is that the US is a federal country. You've got lots of options, lots of jurisdictions, all making policy, some are better than others. In the UK, even though we've got Scotland and Wales and other land on this, they all have similar regimes. Our system is super centralized, so there's no kind of escape valve for any of these pressures.

Michael Lens 22:52

And the interesting thing there, I don't know if we're going to talk about this later, is, you know, there is a movement in the United States to actually centralize land use decision making and kind of these decisions around housing supply, right, to get it out of the hands of local jurisdictions. And, you know, it's very different, I think, to go to a nationalized system that you see in the UK than what we're talking about, which is more state influenced or state run. But I think the UK does clearly show that, you know, centralizing your land use or pulling away decision making power from local jurisdictions is not a panacea, obviously. It's not like going to perfectly solve these issues.

Anthony Breach 23:35

Yeah, exactly. You put it in the right way. So you know, Japan is a country that's centralized, you know, they've got great outcomes across a bunch of dimensions. What's difficult for us is we are centralized across every dimension, especially with local funding and local finance, very, very important for incentives. The one thing we do give local governments lots of power to decide is discretionary power to accept or deny planning applications, so it's the worst possible model for centralization.

Shane Phillips 24:01

All right, so a real focus of this report, which we haven't really talked about thus far is how different countries approached public versus private sector home building over the past several generations, with some countries really focusing on building a lot of private housing, and that's about it. Others building a lot of private and some or a lot of public housing as well. And Britain really as a kind of outlier for choosing to allow relatively little private housing, but building quite a lot of public housing, about 50-50, which is no other country achieved that ratio of public to private. You trace this back to the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947. This coincided with a decline in private home building and a very sharp rise in public sector home building. Public housing in the UK is known as council housing, which is, I think, fairly analogous to how public housing in the US looked and who it served in its early decades, when it tended to be relatively low density and targeted at the working class, somewhere between poor households and solidly middle class households. Like in the US, public housing in the UK also evolved over time, it developed problems with concentrated poverty and the like, but it has fared much better in the UK and still serves a pretty sizable share of the population. I'll have you start by explaining the Town and Country Planning Act, the TCPA, and its effect on private home building first. Then we can talk about how all this relates to public sector home building. So what's the deal with the TCPA?

Anthony Breach 25:35

Sounds good. So I think it's important to understand here that the UK system is so restrictive that we think zoning would be a big improvement, that zoning would be much more flexible than what we've got today. So before 1947, we have a nascent zoning system, the shadow of something like that is starting to emerge. But in 1947, we take a big diversion. You can perhaps, as an ideal type, describe a zoning system as a system in which you have spatially bounded rules that say single family zoning, zoning there, commercial zoning over there. And if you follow the rules by right, you can build. In practice, it's more complicated than that, but that's sort of how their zoning systems work. Our system is quite different in that we don't have zones that decide where development is and is not committed. We have a discretionary system where every decision is taken case by case. And what that means is then you can actually propose something that complies with the local plan. And because it's all judgment-based, it's all interpretation, it's not about what happens on the map, you can propose something that complies with the local plan and it can still be rejected. And that is a feature, not a bug. That is supposed to provide flexibility to planners and the local authority to say, here's where we want development, here's kind of things a bit different, we want that. In practice, it means two really negative things for house building and planning reform. The first is that there's obviously a ratchet. It's very rarely the case that a non-compliant scheme would be granted planning permission as a result. It does happen, but it's very, very rare. It's much more common for a compliance scheme to be rejected by a local authority. But also it makes the process of planning reform much more unpredictable. Because if you have a system in which the rules don't matter or don't matter as much, then changing the rules doesn't really have a big impact on outcomes. Because it's all down to the interpretation of the local authority and how this is filtered through all these hundreds of different councils.

Shane Phillips 27:27

Before we move on, there was a clarification I was interested in. So my naive, very uninformed understanding of the UK planning system, before reading any of your work on this or listening to you elsewhere, was that there was really no plan at all. It was sort of the city, the central government didn't say, here's what we would like to see on this parcel. There's no guidance whatsoever, and it's just completely up to the developer to propose something they think that the council or whomever will approve. Is that not entirely true? And there is sort of plans there. It's just because it's so discretionary and there's so much left up to interpretation that it is functionally might as well not be a plan.

Anthony Breach 28:14

Yeah. I'm afraid it's not true. We've managed to get the worst of both worlds. So we do have local plans.

Shane Phillips 28:22

I'm sensing a theme there. If nothing else, this is a great conversation for making those of us in the US feel a little bit better about our system.

Anthony Breach 28:28

Bring a bit of sunshine into housing pressured lives. So we do have local plans. If you read one, you will be surprised at how few maps are in it. It's not really about this neighborhood can do this or this development allow here. It's actually much more about a list of policies. These are documents that run to contain things like every development must have bicycle racks or every development must have a green roof. Every development must have insulation, et cetera, et cetera. And these run to hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of pages, 500, 600, 800 pages or so that are basically letters to Santa with all these wish lists items on it. And as no development can possibly comply with all of these criteria, an application is made which tries to be as compliant as possible or even actually is compliant. But the criteria are so vague about character or reducing harm to a particular community that it becomes about the interpretation of the authority and how that has manifest. In technical terms, I think it's kind of maybe where it can be a bit different from the US is it will first go to planning officers. So professional planners will look at the application and they will issue a recommendation as to whether it is compliance or not compliant. If it's not compliant, it obviously is bounced back. But if it is compliant, it then goes to a second stage where a committee of local politicians of local councilors then take a vote on whether the development is compliant or not. So it's really like having, if you imagine if San Francisco's planning system was nationwide, that's what we have. Right.

Shane Phillips 29:55

The dream. Yep. You have a quote in the report that sounded very Manvillian. It sounded like a Mike Manville-ism. "The effect is that instead of all land being available for development unless it is prohibited, development is prohibited on all land unless a site is granted a permit or planning permission." I thought that summed it up very nicely.

Anthony Breach 30:27

There you go. So the Town and Country Planning Act was passed in 1947. I guess I'm curious what motivated it and what was the system that it replaced? So we had a kind of nascent zoning system before 1947, a system in which local authorities could set rules and regulations according to density, height, character, design, etc. But any restrictions imposed on landowners would have to be compensated. So if you had a big site and the local planning authority wanted to impose very severe constrictions on what you could do with that land, you would actually get a big payout from the local authority as a result of compensation for your lost land values.

Shane Phillips 30:55

Your version of takings as we have in the US.

Anthony Breach 30:58

Exactly. And this was unpopular with professional planners because they wanted to do loads of planning. They wanted to kind of get stuck in and regulate lots of stuff. Local authorities were thinking, can we really justify increasing our taxes on local residents to implement these schemes when we could actually, by allowing more houses, we could grow our tax base? Probably not. So there was this kind of frustration in the planning profession, parts of the planning profession about this system. However, other countries evolved towards a more zoning based system from that. What's really weird about the UK is we take a particular turn after 1940 with the publication of what's known as the Barlow Report. The Barlow Report was a Royal Commission. There's a very serious official report issued by the British government, a neutral nonpartisan investigation. And the purpose of this report was to look into what are the problems with the over-concentration of the economy in the big cities, and particularly in the Southeast, particularly in London and Birmingham. And it's really got three things that it's particularly worried about. First is that the big cities are a problem, just economically, socially, from a public health perspective, big cities are bad. Second, it's worried about regional inequality. So it's increasingly concerned about, we were talking about Manchester earlier, starting to de-industrialise, this is a real issue that needs attention. And it's worried about this lack of planning power that the planning system as existed then didn't have enough bite into it. We couldn't set up what planners wanted to do, which is set up new towns, new settlements that were planned from the beginning to be perfect. And Barlow sets up three recommendations from this that are kind of unrelated to planning as a practice, or indeed from a technical perspective, but are used to justify the creation of a discretionary system. So to solve the problem of the big cities, it says we should impose urban containment. So we just have policy that explicitly stops the big cities from growing, with the implementation of very large green belts, urban containment zones around the big cities. Actually people should be forced out of the big cities, that they were christened overspill population to be housed in these new towns set up by the planners.

Shane Phillips 32:59

Particularly from the slums and the tenements that were legitimately very overcrowded, but they felt like, you know, we're not going to rehouse them in the city, we're just going to build housing elsewhere and they'll go to another place that needs more population.

Anthony Breach 33:13

Exactly. So rather than building new suburbs on the outskirts of that big city, it's creating a brand new settlement and locating people there. Second to tackle regional inequality, discretionary control over the location of new factories was imposed. So if you were a business owner, if you wanted to set up a new factory, you couldn't set it up in Birmingham or indeed London of the Southeast. You had to apply for a permission and those permissions would only be granted if you located them in declining areas. And that's more like a workforce development policy. Exactly. So the formal title of the Barlow Report is the Royal Commission on the Distribution of the Industrial Population. So it was very concerned with this kind of workforce location and economic aspect to the problem. And third, to deal with this idea that the planning system was too loose, it was allowing too much building. In this 1930s house building boom that we're having, planning controls need to be tightened in some way to allow for planners to deliver housing through new towns. And each of those things together was then the kind of intellectual genesis for a very restrictive land use system that gave local authorities lots of power to compulsorily accept or deny planning applications and actually move away from that kind of zone or base system.

Michael Lens 34:27

Very interesting. So what's all this got to do with council housing, which is the housing built in the UK by the public sector? Can you give us an idea of how council housing first is distinct from privately built housing in the UK and what its boosters would say about why they wanted to prioritize it back then?

Anthony Breach 34:45

Yeah, sure thing. So council housing, simplest form, is housing built by the local council. So you're looking at local municipality built by the council and it's let out. Probably conceived to be for, as you said, either lower middle class or upper working class workers who had the income to occupy a relatively generous, still subsidized high quality space. The idea behind why it becomes much more important after the Second World War is this vision that private sector development would cease to exist, that all development would be taken by local government, by councils, and that the entire community, the entire national community would be housed through the workings of local government in this way. And it would all be financed by these discretionary controls on development, which mean that councils could capture land value uplifts from development and then use that to finance the works of building new council houses. So I think in a way, all this debate is heavily influenced by the ideas of land value capture of Henry George. You might think about this as dark Georgism in a way, right? This is the ideas of land rents inherently being a bad thing of not really telling us about where people want to live or what the density should be, instead of being a purely negative source of society, trying to capture those and deploy them for public ends is what motivates a lot of this, but it doesn't really work even from the beginning.

Michael Lens 36:08

So, Ant, I'm very intrigued by this genesis of a anti-density move that you describe here in the UK. And also, I think this genesis of council housing as maybe a more desirable housing type than purely private, privately produced housing. And I know so little about other countries. I study the United States, and so much of where I go back to in situations like this is how did this play out around similar times in the United States? And as far as the origins of zoning and the origins of anti-urban or low density preferences, we always end up tying these movements to race, probably primarily also class or income biases. So I'm curious, the UK's demographic profile and changes are very different than those changes were in the United States in the mid 20th century. So is there a role of immigration or perceived immigration or race, class differences in the UK that you think explain any of these low density changes or preferences or movements? And if not, what else is going on socioeconomically that might explain some of this?

Shane Phillips 37:37

Yeah, and just to tack onto that, it seems like to have built so much council housing and done it in a way that sort of went alongside suppressing private home building, I'm just curious if there was some specific problem or set of problems people felt that council housing was able to solve or address some needs it was able to meet that private home building had not been up to that point.

Anthony Breach 37:59

Yes. So these are two really great questions. So I think in terms of the racial immigration angle, I don't think that's a cause of the genesis of this system and these patterns. It becomes more salient later on, later in the 20th century when immigration starts to increase substantially. And you do see some tensions in London and around the Birmingham area quite infamously related to this topic. I think class prejudice is certainly part of it. The people who are benefiting from the expansion of the suburbs in the 1930s are primarily upwardly mobile office workers in London and Birmingham. You do see a backlash, the formation of the council to protect rural England. This kind of countryside preservation group is established, you start to see some initial laws against what's known as ribbon development, houses built along the side of main trunk roads in England. And a lot of this is due to kind of aesthetic concerns about the right kind of houses, which then obviously implies the right kind of people and these kind of norms about who is allowed to mix and live and work where. I think a really big part of the impulse as well is, coming back to the Manchester example, so much of Britain's urban form as the first country to industrialise and create these big urban industrial cities, so much of the building stock is just terrible. There is a very, very severe public health crisis in pretty much every urban area in the UK during this period and it is felt. I think justifiably, I can empathise with this position, why they might come to this conclusion that big cities are inherently unhealthy, unsanitary, or kind of a not clean way of living, not suitable for families and for households, and the kind of introduction of motor vehicles and similar provides the opportunity for a kind of new way of living, a kind of modern England in which people have their semi-detached house, their council house with a garden that's clean and has a pleasant building stock. I think, coming on to your question, Jane, I think this is the great tension of the post-war period is that part of the impulse of council housing is a feeling that the private housing boom of the previous interwar period had only delivered for those upwardly mobile people. There was only middle-class households who had benefited from that and actually the large industrial working class hadn't really benefited at all, and part of the idea of council housing is you're going to have the doctor, the butcher, the factory worker all living in the same type of houses in the same street and it's going to be an inherently mixed community as a result of that. However, as we've just kind of maybe got a hint of, the actual impulse behind the planning regime that then created that tenure mix is inherently anti-mixing. It's intentionally kind of segregated on class grounds, and I think eventually part of the reason why it starts to break down is a contradiction to become too great to bear for the amount of building that was going on and what the system was trying to do.

Shane Phillips 40:46

So the UK built a lot of council housing from 1947 to 1979. As I said, about half of all of the housing constructed over that period was council housing, and that is a higher share than any of these other European countries that you looked at. However, even though the UK had the highest share of public sector home building, it had just about the lowest rate of overall home building, and it actually didn't even have the highest rate of public housing development because the overall rate was so low. Other countries like the Netherlands and Sweden built far more private housing during that period, adjusted for the size of their existing housing stock, and they did so while also building public housing at a higher rate than the UK. As you put it, even though the Netherlands and Sweden had a smaller role for the public sector as a share of their tenure mix, both had higher average rates of public sector home building. I think this is something we see pretty often here in the US, implicitly if not explicitly, where the share of affordable units actually becomes more important than the number of households that are served by those units. I guess the questions I want to ask here on behalf of our audience, and me, are why did the UK turn so sharply against private home building and also at the same time so strongly in favor of public housing? I think we've started to get at that, but I'm curious to drill down on it a little more.

Anthony Breach 42:11

Sure thing. I think at the high level, despite what I've just said, I think the term against private house building is something of a historical accident. I don't think it's intentional that we crush total house building by as much. I think there's a real underestimation of just how much private sector house building being reduced would then affect total house building, and that the planning system that we create is much less conducive to developments than we expect. I think it's initially concealed due to the huge efforts that go to increasing public house building, but as those subsidies are withdrawn and the planning system really begins to tighten in the 1960s, problems then fully emerge. Our next paper tries to answer this question in a bit more detail by looking at the geography of where private and public house building are actually located. I can't talk too much about it because you know what researchers are like with stuff that hasn't come out yet. But I guess-

Shane Phillips 43:15

Can't be scooped.

Anthony Breach 43:18

Yeah. Well, I can give you one little scoop. I'd say that the central problem really is that private house building is much, much lower in the big urban areas compared to the rest of the country. Partly that seems to be because it's this Barlow Report idea of deliberately suppressing demand within the big cities. I think it's also the introduction of discretion makes infill particularly difficult. It makes it hard for private sector builders to take existing urban lands, assemble it, and go up. But also it's the introduction of the green belts. We haven't talked about them that much, but they're a very important aspect of British urban planning. You have these enormous urban containment zones that stretch far into the hind limbs of the big cities that prevent pretty much all development, not even on nature grounds, but specifically on the idea that these are areas where development should just not occur because it would make that area more urban. These are very large areas. The London green belt is about three times the size of Greater London itself. The one in the north of England stretches almost from coast to coast, from Sheffield almost all the way up to Blackpool, on the other side of a mountain range. These are enormous areas where private development is essentially banned. The most dynamic third of the country cannot build private sector housing at scale. Even though things are kind of okay elsewhere, those really get worse as time goes on.

Shane Phillips 44:07

Yeah. Well, I think the point about infill being particularly affected by discretionary processes is really interesting. I think it makes some sense when considering that a lot of this is happening, you're having to tear down something that's already there. It's interesting because a lot of the council housing that was built, I just read a book, Municipal Dreams about the council housing system. It's very pro council housing, but it acknowledges it involved a lot of displacement of households because a lot of it was done in this urban renewal spirit and very well meaning, but in some ways it's easier for a government to engage in that kind of action. Whereas if you're just a private developer saying, hey, I want to tear down a bunch of these homes where people live and build, even if it's more of them. When you have a totally discretionary and by nature totally politicized process, who's the elected official who's going to want to vote in favor of that? One more thing I want to get into here or make more plain is this idea that somehow making private home building less desirable, less feasible, more complex advantages, social housing or public housing or affordable housing development. Can you talk about that a little bit? Because I think that's an idea. One thing we hear in the US, even from affordable housing developers, and I feel like they should know a little better, but there's this sense that if we didn't have these private developers trying to build market rate housing in the city, or we had fewer of them, then it would be easier for them to get land and therefore we would just build a lot more affordable housing or be a lot more affordable. I don't think there are many places that bear that out in reality, but I'm curious to hear your thoughts about the experience of that in the UK.

Anthony Breach 45:52

Yeah, sure. So I think this may be a way to talk about the transition from that initial very early post-war purely public regime to the more mixed regime we see afterwards. So the Labour government immediately after the war, which introduces the 1947 TCPA, inherits an economy that's obviously on its backside, basically. There's very severe rationing of all kinds of things, not just meat and butter, but even things like bread are rationed for the first time after the war. And that also includes things like iron, steel and building materials as a result of these controls. And basically the public sector house building, you're trying to recover from bomb damage, you're trying to deliver on these new towns, also just generally growing population needs that you need to meet anyway. The public sector house building that is launched after the war is not even able to scratch the surface with these needs. Probably building about 150,000 houses every year, or maybe even less than 100,000 or so immediately after the war, which is vastly insufficient compared to actual need. What happens then is that this becomes a very salient political issue, that you've got a big divide between Labour and the Conservatives on, a, controls within the economy, but also kind of a record for improving living standards. And at Conservative conference in 1950, essentially the membership, like the crowd of Conservative members, revolts against the leadership and starts chanting that they're demanding 300,000 houses every year. And eventually the politicians on the stage, almost in terror, accede to the mob and say, okay, fine, we'll have a target of 300,000 houses every year, we'll release the controls, we'll allow the free markets to get involved, but we're going to do this. And Churchill, who's back in power after the next election, appoints a guy called Harold McMillan to be his housing minister. And he removes a load of these rationing controls on building materials and allows the private sector to get involved in development again, removes a lot of those land value capture mechanisms that were really killing the incentives for development to occur. And there's then kind of a diminished, but still substantial post-war housing boom is then driven by the rapid increase of the private sector alongside a remnant of public sector house building over that period. What's kind of interesting about public sector house building is its nature changes a little bit over this period as well, as you've sort of just hinted at. Initially, public house building is sort of everywhere. You do see it in the suburbs of places and on the outskirts of big cities. However, by the 1960s, that's really changed, and public sector house building becomes much more about slum clearances, about urban renewal, and these kind of mass demolitions that we're just discussing.

Michael Lens 48:23

Ant, at times, I think this narrative about land use regulation in the UK might sound like there was a whole bunch of home building coming right out of the war, and then it was a continuous decline from 1947 onward after the TCPA passed, especially for private housing as we discussed. But in reality, private home building grew pretty dramatically from about 1950 to the mid 1960s. So what happened over that period and then what was responsible for the downward trend it's been on over the last 60 years or so? My impression from the report is that the approvals process only became more restrictive over time, but you're only really able to hint at those details in the report. And if I can add on, something that we've already been discussing is greenbelts. And when I was in the UK, I was in a conversation, I think it was with Professor Paul Cheshire at LSE, London School of Economics, and he was really talking to me a lot about greenbelts and how important this is. So I want to kind of re-emphasize or give you a little space to re-emphasize what you know, and what we know as a field about the role that greenbelts have played in restricting housing availability or affecting housing markets more broadly.

Anthony Breach 49:50

Yeah, great question. So Paul Cheshire is one of those giants whose shoulders we're standing on, right? He's one of those guys. From the beginning, he saw it all. He'd worked it out and he's been banging the drum for so many years. And finally, people are starting to listen. I think the greenbelt was a really important part of the story. So I've just talked a little bit about how Harold McMillan in the Churchill government and later as PM on his track record in housing delivers a big private house building boom during the same time as that government. This is kind of where some of that class segregation stuff comes in a little bit. That same house building government introduces in 1955 a circular, so it's not even a law, it's not even parliament has decreed this. This is basically an opinion written by a government minister that is circulated to councils and says, well, we think it would be a good idea if you imposed greenbelts around your big cities and around your urban areas and those areas in which house building was banned. You immediately get a big response by a lot more affluent areas that don't want to see house building. They adopt this policy, they implement it into their local plans. They sort of sketch out where they don't want developments there to happen. From what I can tell, it seems to be a little bit based around so many intricacies of local finance during that period. In that if you were a small borough council, a little kind of municipality, if you grew enough, you could be promoted to a full-sized city. It's maybe the simplest translation.

Shane Phillips 51:20

You love your promotion systems in the UK. You get it for soccer, you get it for cities.

Anthony Breach 51:28