Episode 80: Inclusionary Housing Goes International with Anna Granath Hansson

Episode Summary: Inclusionary zoning policies are commonly used to produce affordable housing and “social mix” in the U.S., but what about in Europe, where public housing and strong social welfare programs have historically met those needs? Anna Granath Hansson shares research on emerging inclusionary housing policies in the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark.

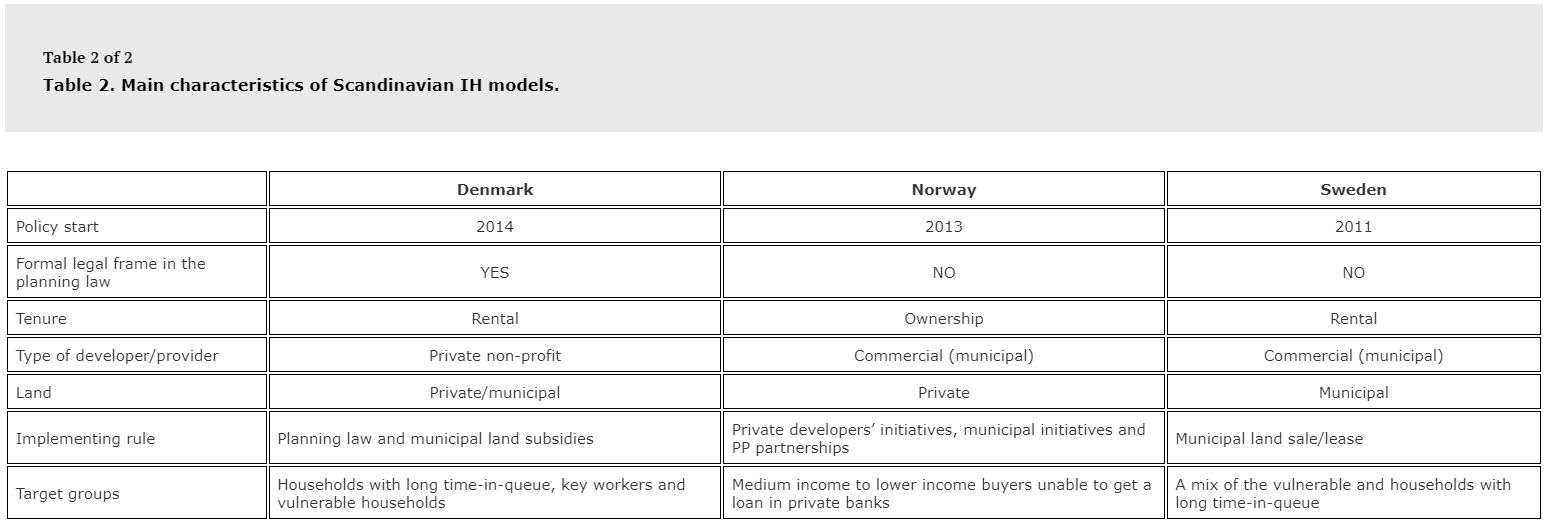

Abstract: Inclusionary housing policies, aiming at creating both affordable housing and mixed neighbourhoods through land use regulation, do not have a long history in Scandinavia. Although Denmark, Norway, and Sweden have traditional welfare state perspectives on equal opportunities and housing, the use of the planning system to implement policy is hesitant. This article outlines the diverse political backgrounds and influences from housing and planning systems that explain this paradox. Further, differences between the housing and planning systems in the three countries are well illustrated by the varying interpretations of inclusionary housing policies. Policy results, in terms of affordability and social mix, play out very differently in the given contexts. The article in this sense adds to the scholarly conversations about barriers and opportunities for IH policy implementation, by contextualizing the conversation with implications from within systems that are relatively homogeneous and aiming for redistribution and equity. This raises questions about when, if, and how IH policy is the appropriate approach.

Show notes:

- Granath Hansson, A., Sørensen, J., Nordahl, B. I., & Tophøj Sørensen, M. (2024). Contrasting inclusionary housing initiatives in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway: how the past shapes the present. Housing Studies, 1-22.

- Previous episodes on inclusionary housing/inclusionary zoning:

- More information on the EU court case about Denmark’s “ghetto law.”

- Sightline article on Portland’s fully-funded affordability mandate.

- “Despite relatively large construction volumes, the larger Scandinavian cities increasingly struggle with housing affordability, not only for low-income but also moderate- and mid-income households. Commercial property developers and other non-public actors are expected to build the larger share of new housing (Tunström, 2020), while affordable housing vehicles (primarily public housing) are used less towards the overall goals. Although the Scandinavian states and many cities express a wish to promote affordability and social mix, the desire to use instruments that can be associated with what the literature has labelled IH has been hesitant to date. This paper explores attempts in the Scandinavian countries to use policy that could be categorized as IH with the aim to understand this hesitancy and why IH projects are implemented differently in the three countries. The study connects to the international literature on IH offering additional case studies highlighting political goals, legal foundations, organizational and economic prerequisites, and the potential of IH as an affordable housing vehicle, assisting in elucidating the role IH might play (or not) in different types of governance systems. The Scandinavian IH cases are especially interesting as they explore the transition from housing-centred policy to planning policy that ties together affordable housing and social mix.”

- “The main aims of IH policy are to extend affordable housing supply and create socially mixed neighbourhoods (Calavita et al., 1997). Calavita & Mallach (2009, p. 15) defines IH as ‘land use regulations that require developers of market-rate residential development to set aside a portion of their units, usually between 10 and 20%, for households unable to afford housing in the open market. Alternatively, they can choose to pay a fee or donate land in lieu of a providing units. In a European context, de Kam et al. (2014) establish that IH policy might also include municipal land provision at below-market price, land situated in locations that create social mix, and the subsidy of projects out of development gains.”

- “IH policy aims to enlarge the supply of affordable housing and create socially mixed neighbourhoods. However, both these claims have been contested. As summarized by Li & Guo (2022), IH has been criticized for producing limited amounts of affordable housing and having a negative impact on housing supply (partly contradicted by Mukhija et al., 2010), and to increase development cost (Kontokosta, 2014), and house prices (partly contradicted by Hughen & Read, 2014). Hughen & Read (2014) suggest that developers are likely to respond to policies by strategically altering decisions on where and how to invest. Li & Guo (2022) also point to developers’ avoidance strategies when faced with mandatory IH policy and the need for better evaluation of potential alternatives as well as regional approaches to maximize effectiveness and minimize negative impacts on housing supply. Li and Guo, however, find it unlikely that voluntary, in contrast to mandatory, IH policy would restrain housing supply. Further, socially mixed neighbourhoods are generally viewed as important in European housing policy (e.g. van Ham et al., 2016) and this goal is especially underlined in the egalitarian Scandinavian policy environment.”

- “The above-mentioned Musterd & Andersson (2005) find little correlation between the mix of housing type and social mix in a study using Swedish data. Arthurson (2002) questions the correlation between socially mixed neighbourhoods and social cohesion and Galster & Friedrichs (2015) state that it is mainly large concentrations of people with socioeconomic difficulties in the same neighbourhood that is problematic as it has a negative influence on development possibilities of individuals. In the same vein, Hedman et al. (2021) state that people’s exposure to various societal groups and different urban textures is mainly explained by mobility patterns, not housing location. Galster (2007, p. 35) claims that ‘the common policy thrust toward neighbourhood social mixing must be seen as based more on faith than fact’.”

- “In Denmark, 57% of the population lives in owner occupied units and the other 43% is distributed on private rental, Non-Profit Housing (NPH, Almene Boliger), and cooperative ownership housing. In 2023, there was a total of 567,547 NPH units (Statistics Denmark, 2023) with close to one million residents, which is ∼1/6th of the total Danish population (Dansk Almene Boliger, 2023). The work that led up to implementing NPH, dates back to the 1880s when goals that tie together social welfare and affordable rental housing were formulated (Martens Gudmand-Høyer, 2018) … To promote NPH in cities, a purpose-provision was added to the Danish Planning Act in 2015 to promote versatility in housing composition through the option of planning for the establishment of NPH in cities. The land on which IH projects are built is mainly owned by NPH associations making them both developers and long-term operators post-completion.”

- “Today, policy related to NPH has two main goals, first to promote affordability for low- and mid-income groups who are struggling to find housing in the larger cities in Denmark. Secondly, the law on NPH has been amended to particularly focus on desegregating certain vulnerable NPH areas, mainly by mixing forms of ownership (Seemann, 2021). This second element has been presented as striving towards mixed neighbourhoods which fits the IH narrative but at the same time, the policies reduce the total amount of affordable units in vulnerable areas and therefore work against IH goals. As a result of the law amendment, new NPH is only built outside of vulnerable areas.”

- “The legal foundation for NPH is mainly split between the Planning Act and the Law on Non-Profit Housing. Since 2015, the Planning Act includes a provision that allows municipalities to require, that up to 25% of the housing stock in a new residential area must be NPH. While these units are assigned regardless of income and based on a waiting-list, municipalities have referral rights to typically 25% of the units with the aim of housing vulnerable households (Bolig- og Planstyrelsen, 2021). Additionally, an alternative option for municipalities with high growth in population is to subsidize land purchase expenses (which would otherwise be prohibitive) … These tools include economic incentives provided by the state and municipalities to make NPH development feasible in collaboration between private and non-profit stakeholders. The actual implementation of the laws at the municipal level is closely tied to local plan approval. NPH is in general more affordable than private rental but not necessarily affordable for all lower or mid-income households in Copenhagen and a few other large cities. However, there are several housing subsidies that individuals can apply for based on household needs that in some cases make it possible for low-income tenants to live in higher rent units.”

- “The NPH sector consists of member-owned housing associations set up for the purpose of constructing and administering affordable housing. Each development is independent both legally and economically. Non-profit housing is tightly regulated through the Law on Non-Profit Housing. Therefore, while not state-owned, the state has great influence and power over this part of the housing sector. The law requires a decent housing standard that centres cost and durability and does not allow for excessively costly extras. It has a maximum total cost set by the Minister of the Interior and Housing. Additionally, municipal interest- and instalment-free loans for 50 years, and government secured mortgage loans, are provided. Two percent of development costs are resident deposits.”

- “The stakeholders involved in developing NPH vary depending on initial landownership. When private developers own land, they might be required by the municipality to transfer a part of it to an NPH organization such that NPH can be included in the development area. The Minister of Housing and Planning admits that it can have a negative effect on the incentive to invest in private housing if a local plan requires up to 25% NPH because it de facto implies that private property owners are required by the municipality to forcibly sell a piece of land to a competing NPH association (Urban & Housing Committee, 2015). However, the rationale behind the entire regulatory setup is that the profit margin in some areas is large enough to motivate private developers to exchange land for an approved local plan.”

- “A recently published evaluation of the 2015 Planning Act provides a summary of the use of the 25% regulation in local plans from 2015 to 2020 and shows that out of ∼1700 local plans related to housing development, only 45 included a demand for a percentage of NPH (Ervervstyrelsen, 2021). Early indications point to local differences where the level of housing market heating could be determined. Aarhus municipality appears to get more non-profit housing implemented using the local plan provision than Copenhagen (von Fintel, 2021). A broader evaluation of implementation shows limited success. Within the 45 local plans with non-profit requirements, 10,400 new homes were built as of spring 2021, and of these 635 are non-profit units (6%).”

- “Although the majority of Swedish households own their home, about a third are tenants and about half of rentals are owned by municipal housing companies (Statistics Sweden, 2023). Swedish housing policy from the 1930s onwards focused on public rental housing provision effected through municipal planning monopoly, extensive public land ownership, state financial subsidies, and municipal housing companies (Bengtsson et al., 2013). A gradual change in policy towards market-oriented solutions took place in the aftermath of a financial crisis in the 1990s. For many years now, policy has focused on the construction of large volumes of new housing units by both public and private developers. Only recently, a discussion on what types of households have the economic strength to access this new housing has emerged. To counter critique, a few municipalities have started developing IH models with the aim of creating affordable housing and a greater socioeconomic mix in new housing areas (Granath Hansson, 2021).”

- “The intent of the Swedish IH approach is to create affordable rental housing targeting low- or mid-income households and thus generating social mix. The share of affordable housing in each project spans between 20 and 100%, with a 15-year time limit for reduced rents. The unitary housing system focuses on ‘good housing for all’, favours housing queue systems using time as selection criteria, and shuns means-testing. As time-in-queue has proven less efficient at reaching younger and lower income households, various alternative letting strategies are used. In some projects or parts of projects, strict time-in-queue rules do apply, but in others, a first sorting of applicants is made based on other parameters … Explicit targeting of households with lower income from employment, such as key workers, is not on the agenda. However, the emphasis on time-in-queue solutions can be interpreted as a wish to also reach these groups.”

- “IH is realized in a negotiation process between municipalities and developers where developers are invited to propose a project to be built on municipal land. The negotiations result in a development agreement and a land sales or lease agreement. Developers are not officially a party to the local plan, but in reality, it is in many cases developed to fit the negotiated project conditions. Possibilities to keep rents low for a certain period of time have stirred some discussion. Swedish rental law is based on rents that are collectively negotiated between the Tenants’ Union and property owners and does not foresee separately determined rents in single projects. However, in new buildings, rents may be set according to a separate rent system for 15 years which allows for higher rents that better match investment cost. In IH projects, this system is reversed to instead allow rents that are lower than regularly negotiated rents.”

- “Swedish municipalities adjust land prices and leases to the restricted economic potential of affordable housing projects. Compared to the most profitable land use, restrictions demanding affordable rental housing often result in significant losses of municipal income. Granting leaseholds spreads municipal income over a longer period of time and hence also impacts municipal income streams … To attract developers to participate in IH projects, municipalities offer incentives, such as priority in municipal processes, larger allocations of municipal land, and municipal land to build not only affordable housing but also standard rental housing or tenant-ownership apartments. Some regulatory relief is also granted. Further, the portion of affordable housing in each project is decisive for project calculus and municipalities have been open to suggestions from developers on portions deemed feasible (Granath Hansson, 2020).”

- “In Sweden, a limited number of municipalities have implemented IH models in a few testbed projects. Rents applied are considerably below standard rents in new-built rental housing. As follow-up studies of households moving into the created housing have not been made to date, and the question of whether the models reach lower and/or mid-income households cannot be answered, the efficiency of models can currently not be analyzed or verified empirically. As implementing projects has extensive impact on municipal economy, mainly tied to the use of municipal land, and include institutional uncertainties linked to the regulation of rents and allocation of apartments, municipalities might hesitate to scale up models, at least before a solid outcomes analysis can be made.”

- “Norway is a nation of homeowners. The post-WW2 rebuilding scheme activated local and central governments to provide homeownership in modest homes for all kinds of households. Cooperatives, condominiums, and detached houses were built and sold to the general public at prices reduced by state subsidies and price regulation on land acquired by the municipalities. When the housing shortage was overcome and politics became conservative in the 1980s, subsidies and price control were dismantled (Annaniassen, 2006), condominiums and cooperatives became market housing and private developers took over the task of providing building land. In what Sørvoll (2011) terms the ‘social turn’, housing policy refocused on how to assist lower income households to purchase a home with the help of means-tested policy instruments, such as housing allowance and adjusted mortgages. The adjusted mortgages are means-tested and counselling is provided to the household before and after purchase (Holm et al., 2020). Lenders’ risk is shared between the municipality and the state, and default on payment is rare (Husbanken, 2020). The policy should be understood in the context of a tax system that favours home ownership, a small and expensive private rental market, and very limited council rentals. In this context, assisting lower income households with ownership has proven to decrease the annual cost of living of eligible households compared to renting (Husbanken, 2020).”

- “An underlying, but not so frequently mentioned factor adding to the rising prices is the Norwegian compact city policy (OECD, 2022). Supplying new homes through densification is interwoven with urban renewal and outdoor upgrading. Negotiating developers’ contribution to public goods is practised in all growing municipalities. An amendment of the Planning and Building Law in 2006 streamlined the negotiations between developer and municipality and introduced a passage for municipalities to compensate developers at market rate if the municipality wanted to purchase new homes from developers for use in their social housing policy. Thus, the municipalities have the right to require developers’ contribution to black, grey, green, and blue infrastructure, but not affordable housing. In 2008, a full revision of the planning and building law strengthened municipal strategic planning, but never raised the question of whether the act should include measures to ensure social-economic mix in new urban developments.”

- “The initiatives that resemble IH in Norway, gained wind from market actors rather than from policy makers. Politics are in the process of catching up and streamlining institutions to facilitate up-scaling. At present, 20–30 developers are delivering affordable purchase schemes. Some municipalities establish their own rent-to-buy models on municipal land with municipal entities constructing the new housing. Municipalities tend to set lower rents and include savings in the rent. Further, some require more than five years of residence in the municipality for applicants to be eligible (Christiansen & Nordahl, 2024). In 2020, the City of Oslo launched a private-public partnership with two private developers, targeting 1000 new units annually, over a period of 5–7 years.”

- “Scandinavian cities follow the assumption that mixed housing creates social mix. In this paper, this assumption has also been a critical component. Mixed housing can both relate to mixed housing types and mixed housing tenures. In Norway, mixed housing types have been expected to generate socially mixed neighbourhoods. What is new in IH policy is that it tries out a tenure mix in the form of intermediary tenures implemented through assisted purchase models. In Denmark, the tenure mix is already in focus: NPH is being built in areas where this form of housing is not already present in larger numbers, while NPH is not constructed in areas where this tenure dominates the housing supply. In Sweden, both housing type and housing tenure mix are used in policy to create social mix, but IH policy mainly works to introduce affordable rental housing in areas dominated by tenant-ownership thus focusing on tenure mix.”

- “Path dependency (Bengtsson & Ruonavaara, 2010) is evident after uncovering the traits of each country’s IH attempts, as these attempts are closely aligned with long-standing institutions in each country. The most pronounced differences between the countries are the choice of tenure and the mode of policy enactment. In Denmark, the long-standing NPH sector has been operationalized and policy enacted through law. Swedish policy focuses on rental housing and, as there is no national IH initiative, municipalities formulate policy on the local level. In Norway, there are beginning discussions about introducing requirements related to lower-cost ownership schemes in the planning law, and specific suggested changes in the housing laws, which align with Norway’s long history of extensive home ownership.”

- “Currently, housing development in many Scandinavian cities is in a transition phase where high levels of sales have been replaced by low sales levels and cancelled projects. In the years to come, there will probably be less new housing and municipalities might experience increasing difficulties to incentivize developers to take part in IH schemes which could severely hamper policy outcome. Low levels of construction might also lead to price increases in growing cities. However, new market prerequisites might also lead to innovation driven by a need to act on housing shortage by municipalities and/or a will to stay in the market by developers. Land ownership might also motivate both private and public developers to find new ways to activate their assets. The ways in which these diverse incentives play out will be decisive for the availability of new affordable housing and social mix in new housing areas going forward.”

Shane Phillips 0:05

Hello! This is the UCLA Housing Voice podcast, and I'm your host, Shane Phillips. This is the last episode from our short series on inclusionary zoning, a conversation with Anna Granath Hansson about inclusionary housing policies in Scandinavia.

Inclusionary housing, as a reminder, refers to a range of policies intended to produce housing that's affordable to people across a broad range of incomes. Inclusionary housing has a particular context here in the US. Here, housing provision has always been a pretty market-oriented enterprise, and inclusionary policies reflect that. Nations like Sweden, Norway, and Denmark have very different histories and contexts from our own, but over the last few decades they've moved to adopt their own policies to promote social mix, and so we were curious to learn more about how things are going. Despite the similarities between these three Scandinavian countries, their approaches are all quite different. Each serves somewhat different goals and faces different challenges, and I think they also each offer different lessons for how these policies might evolve in our own backyards.

The Housing Voice podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies with production support from Claudia Bustamante and Gavin Carlson. Send me a message if you've used the podcast or something you learned from it in your work or advocacy, in the classroom or another educational setting, and any other ways you found it useful. These testimonials are a big help for demonstrating our impact to potential funders. As always, you can reach me at shanephilips@ucla.edu. With that, let's get to our conversation with Anna Granath Hansson.

Anna Granath Hansson is a Senior Research Fellow at the Nordic Research Institute Nordregio and is also associated with KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, and she's joining us today to talk about inclusionary housing policies in Scandinavia and what those of us in the U.S. and elsewhere can learn from them. Anna, thanks for joining us and welcome to the Housing Voice podcast.

Anna Granath Hansson 2:16

Thanks. It's nice to be here.

Shane Phillips 2:18

And my co-host today is Paavo. Hey, Paavo.

Paavo Monkkonen 2:21

Hey, Shane. How you doing? Hi, Anna. Nice to meet you.

Shane Phillips 2:23

Before we do our tour, maybe we should talk about what is Scandinavia and what is not because I think if we did not have this conversation immediately before starting recording, I might have said we have our resident Scandinavian co-host on the show, but that would not be accurate would it?

Paavo Monkkonen 2:40

I am not Scandinavian, nope.

Shane Phillips 2:43 So what is?

Anna Granath Hansson 2:45

Yeah, so Scandinavia is Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, opposed to the Nordics, which is Iceland, Finland, and the Scandinavian countries.

Shane Phillips 2:54

Okay. Okay. So the Nordics is just a – the Scandinavian countries are like within the umbrella of Nordic. Any commentary on why things are divided up that way?

Anna Granath Hansson 3:06

Because they are on the Scandinavian peninsula and they used to have very close bonds going back in history.

Paavo Monkkonen 3:14

Whereas my people were very, very special swamp people descended from Mongols.

Anna Granath Hansson 3:20

As I said before, the Swedes love the Finns.

Paavo Monkkonen 3:23

Yes, Sweden and Finland are very close.

Anna Granath Hansson 3:25

They have really close ties.

Shane Phillips 3:26

All right. So that's a nice lead into our tour. We always ask our guests for a tour of a city or town, somewhere they grew up, somewhere they lived at least long enough to know well, and that they want to share some highlights of with our listeners. So Anna, where did you pick?

Anna Granath Hansson 3:41

So I chose to take you on a tour of my hometown, Stockholm. That's the capital of Sweden. This town was built on water between the Baltic Sea and the big lake, Märlanden. And it was founded in 1252, although people of course lived here for much longer than that. And the water and waterfronts is really a defining character of the town and it's really beautiful and enjoyable. But this could of course potentially be a nuisance also because of transport problems. But we have a really nicely built up public transport network that deals with that. So we can just enjoy these waterfronts, a bit like in Venice, we would like to think. But I would like to take you to three places. And the first one is the old town. It's a really small island in the middle, which used to be the whole city for a very long time. But today it's featuring some winding cobblestone streets with beautiful houses and palaces and churches, and of course the royal palace because Sweden is a kingdom. And there's also the quay, which used to be the main trading harbour, but today features a lot of entertainment ships and the occasional visiting royal cruise ship. So it's a really nice place that everybody who comes to Stockholm must see. So since we are all interested in housing policy, I would then like to take you to two areas that are key to understanding Swedish housing policy. And the first one is Tjänstärning Gible. It's a really big serial housing estate that was built in the 60s and 70s. Sweden has been plagued by housing affordability crisis before, and this area was an outcome of that crisis where the government decided to invest in a million new homes in 10 years. And here you can see the result of that. Today these areas are struggling with a lot of social problems and an overrepresentation of migrants. So it's really interesting to study how these areas have developed, and it's a very common topic of discussions. And then the other area that I really recommend you to see is Norrádur Góttstada. It's a completely new development area, which has been framed as a showcase of environmental sustainability. And here you can experience a lot of interesting experiments with different building techniques, waste disposal systems, green space, sustainable heating systems, mobility solutions, and so on. It is also placed on the border to Sweden's only national park that is in a city. So it has woods and proximity to the sea and many attractive features. However, there is no affordable housing in this area at all, which is quite interesting. So that's the tour that I would like to recommend you.

Paavo Monkkonen 6:41

Yeah, I'd love to visit some of the million home program houses. I feel like that's such a useful anchor point. Like in California and the United States, they often have been coming out with these ambitious housing construction goals. So California was 3.5 million over 10 years, which is much less actually than Sweden's population in the 60s was like 8 million or something people. And first of all, they actually did build a million homes and it was a much bigger goal than even the new proposals in the US at the federal level have.

Anna Granath Hansson 7:12

Yeah, we will come back to that later when we start to talk about the stationary housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 7:18

The legacy of the million home program is not as great as the actual production of the time.

Anna Granath Hansson 7:24

There are mixed results, let's say.

Shane Phillips 7:26

As always, yeah, I guess if Sweden had 8 million people at the time and actually did build a million homes in 10 years, that would be the equivalent of California building 5 million in 10 years. For the past decade or so, we've built about 100, 120,000 a year, so a little over a million total. It has not gone well. So getting into this article, this conversation is about an article that appeared in Housing Studies earlier this year titled, Contrasting Inclusionary Housing Initiatives in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, How the Past Shapes the Present. Anna was the lead author on this one, and I'm going to provide her co-authors names in my American accent and actually invite her to pronounce them correctly. But her co-authors were Janni Sørensen, Berit Irene Nordahl, and Michael Tophøj Sørensen. Now please, Anna, pronounce these correctly for us, because I don't want to offend.

Anna Granath Hansson 8:22

It's Janni Sørensen, Berit Irene Nordahl, and Michael Tophøj Sørensen. Perfect.

Shane Phillips 8:29

I was close on the first one at least. All right, so this is an exploration of inclusionary housing policies, or inclusionary zoning, as it's sometimes called here in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. We've been on a bit of an IZ kick the last several episodes with our discussion of the mandatory housing affordability program in Seattle, a re-airing of our interview with Emily Hamilton, and my conversation with Mike Lens about my own analysis of inclusionary zoning here in Los Angeles. So we thought it would be nice to get an international perspective as well, and maybe a bit less IZ skeptical than some of the perspectives that we have presented so far. Inclusionary housing is actually much newer in these countries than in the US, and we will get into some of the theories about why, but their approach is also in some ways quite different from what we're doing in most US cities with IZ, often with more support on the public side to actually make the programs work. For each country, ANA reviews the political focus and goals of its inclusionary housing policies, its regulation, organization, and economy, and outcomes at a high level, and so we're going to get into as much of these findings as we can and see what lessons there are to learn. I asked this offline of Anna just before we started here just to get a sense for how much housing is being built in each of these countries. They don't have million home goals these days, so they're not quite the rates of the 60s, I would say. I think they're all maybe 2023 numbers, but Denmark built 37,000 homes, Norway 28,000, and Sweden 65,000. Adjusted for population, which ranges from about 5 to 11 million in these countries, they're all roughly the same, and not a ton of housing, but not a super small amount. I think that's just important context because inclusionary zoning is so dependent on how much housing is being built overall, it sort of sets a cap on how much affordability it can really produce. Moving us off with a bit more context, Anna, you make the point early in the article that although you're studying three different countries, this isn't really a comparative analysis because Denmark, Norway, and Sweden share so many of the same values, or at least very similar values. Could you explain some of those similarities as you see them? One thing I will point out is it seems like the emphasis on social mix, quote unquote social mix, in urban policies is particularly strong in Scandinavian countries, whereas in the US it feels more like something we maybe pay lip service to but don't necessarily prioritize. My experience talking about inclusionary zoning or inclusionary housing here in the US is that if people are challenged on the affordability benefits of these policies, they may mention that it also has benefits for class or race integration or access to opportunity, which is how we often talk about social mix here. But producing affordable units still in the US seems like the central goal for us.

Anna Granath Hansson 11:21

Yeah, so in Scandinavia, social mix would be the first priority above affordability. So there's a large difference there. And I think that the three Scandinavian countries are famous for their egalitarianism and strong social safety nets. And this comes with the social norm that everyone has the same value and should have the same opportunities. And this also means that no one should have priority above anyone else or have to stand out as poor. It's also very important. So means testing is shunned to as much as possible, except perhaps when it comes to housing allowances, that is the greatest exception to that. This used to be linked to a norm that everybody also has the responsibility to contribute to the common good by working and paying taxes. But this is not so important anymore, let's say. And in city and housing development, this egalitarianism is often translated into social mix. And policy is often based on the idea that everyone should be able to live everywhere or at least be able to participate in the public life everywhere. However, social mix in the new housing areas is really difficult to achieve when you cannot prioritize anyone. So usually social mix translates into tenure mix or housing mix. And that is not really an efficient tool to achieve the social integration that is the ultimate goal of this policy. And also research recently has challenged this idea also in a Scandinavian context.

Shane Phillips 12:56

Can you say a little more about why tenure mix, meaning essentially mixing renters with homeowners is not an adequate means of ensuring social mix?

Anna Granath Hansson 13:06

Because it's applied in new housing areas and new rental housing is also really expensive and not accessible to everyone because it's not subsidized.

Shane Phillips 13:18

So you mentioned this, but another important distinction between the US on the one hand and Scandinavian countries on the other is that Scandinavia and really a lot of Northern and Western Europe are generally places with much stronger social safety nets. And most germane to this conversation, they're also places where the public sector has generally played a much stronger role in building affordable housing. The US has had inclusionary housing policies in some cities as far back as the 1970s. But you're right that in Europe, it's much more a phenomenon of just the past couple decades really. I think that may sound backwards to some listeners, but I think it makes more sense when you understand inclusionary housing as a fundamentally market oriented policy, an attempt to provide affordable housing using market mechanisms instead of or complimentary to or in addition to the public sector. Presumably something is driving these countries toward a more market oriented approach themselves. So what can you say about what some of those drivers are?

Anna Granath Hansson 14:19

To explain this, we might have to go back a bit in history. After the Second World War, the Scandinavian countries were dominated by social democratic policies for several decades, where the state was seen as the main driver in society, including housing development. This entailed a strong political backing and financial support to public housing and the cooperative movement and their housing developers. And Sweden, for example, had this million homes program between 1965 and 1974. And in the 1990s, politicians perceived the housing crisis as solved. So there were no problems and we had a sort of housing market imbalance, they thought. Moreover, this massive investment cost a lot of money and in combination with other external shocks to the economy and pressures, these programs, these housing programs were discontinued. Not only in Sweden, but in all the three countries, politics got more market oriented and irrespective of shifting political majorities. And public and publicly supported housing grew more business-like, as did the housing developers in the cooperative movement. And suddenly, private developers were also expected to contribute to the common good by building affordable housing. And in this new policy environment, where public housing entities were not seen as the sole responsible for affordable housing development, new tools to make private developers also participate in affordable housing development were sort of looked for. And then, inclusionary housing policy was, of course, an obvious choice.

Paavo Monkkonen 16:01

I wonder whether the EU regulations on subsidized housing played a role. I mean, I understand they're a pretty big deal in Sweden in terms of the restructuring of what it terms social housing and changing definitions. I don't know if they played a role in this as well.

Anna Granath Hansson 16:17

This is a... We could make a podcast just on this issue, because it's very heatedly debated. But yes, since Sweden chose not to have any social housing, we are not allowed to subsidize to a larger extent. So...

Paavo Monkkonen 16:37

Yeah, I mean, that shift, this idea that social housing providers, because they were getting so much benefit from the government, then they had to target more towards lower income households in order to fulfill their mission, because otherwise they would be kind of doing illegal competition with private developers.

Anna Granath Hansson 16:56

Yeah, and the municipal housing companies in Sweden are very strong, financially strong, and they have a clear voice in society. They opted for not becoming social housing providers and just catering for the vulnerable. And then, of course, they cannot use subsidies. We will see now with the new EU housing commissioner if that will be changed.

Shane Phillips 17:22

I think we've talked about this once before, at least, but I feel like I'm still not 100% clear on what choice the Swedish social housing providers were kind of forced into. Who were they providing housing for, and who are they now after those EU laws were promulgated?

Anna Granath Hansson 17:38

Sweden has traditionally been applying a universal housing policy. That is to say that there should be no social housing, but everybody should be able to live everywhere irrespective of what companies are providing the service, so private and public should be the same. And in 2010, the private property owners brought this issue to the EU. They said that, like Pavel mentioned, that public housing companies have benefits because they're subsidized by public money, and that creates unfair competition. And so, the Netherlands and Sweden had to make a choice. Do you want to turn your municipal housing companies, or the equivalent in the Netherlands, into social housing providers that can only cater for the vulnerable or less income-rich groups? And the Netherlands chose to do this, and Sweden said, no, we don't want social housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 18:36

One other thing that was helpful for me to understand the Danish context was when I was there last year, the idea of social housing or non-profit housing providers being a public option for housing, right? So it wasn't like these institutions created just to serve lower-income households. They were created to serve everybody, and they're a public option that's going to be just as good and kind of follow similar rules as private housing providers.

Anna Granath Hansson 19:02

I think the Danish cooperatives did something really nice. Don't take that in the room. I think the Danish model is something very exotic, because it's private housing or cooperative housing that partially is state-supported and therefore also have a social role to play. So there you can really talk about social mix.

Shane Phillips 19:28

All right, so Anna, as I mentioned, you summarized some of the key attributes of inclusionary policies in each country in this article, and I want to run through some of the highlights from these. We'll just take these countries in the order they're discussed in the article, starting with Denmark. Could you start us off by summarizing who is served by inclusionary housing there, how it's regulated in terms of incentives and mandates, and then the role of the state or municipalities in assisting inclusionary projects financially? And feel free to mention anything you think is important that doesn't fit neatly into those categories.

Anna Granath Hansson 20:03

So the Danes focus much of their housing policy to their social housing sector, which is called al-Manaboulia, housing for all, if you translate it. And this sector is not a public but publicly supported sort of cooperative housing, where municipalities get the right to allocate apartments to households that they choose in exchange for subsidies. And since 2015, there is a stipulation in the Planning Act that makes it possible for municipalities to demand up to 25% of this affordable housing in all housing projects. And in general, Danish social housing is targeted to low and medium income groups, quite a wide spectrum of people, including key workers, and the municipalities then use their up to 25% allocation rights to house vulnerable groups or households that they want to see in a certain neighborhood.

Speaker 1 20:40

And are these generally, I mean, in terms of the specific projects, these are larger scale projects, redevelopment areas, rather than 25% of a 30 unit building? Or does it go down to the small scale of development?

Anna Granath Hansson 21:15

There is a limit to how small scale it can be for this Planning Act to apply. So the really small project, it doesn't apply to, but it doesn't have to be hundreds and hundreds of apartments either. I don't remember the exact figure, maybe 30 units or so.

Shane Phillips 21:31

You mentioned that these are cooperatives. I think the conception of a cooperative here in the US is just as an ownership structure. I'm guessing that this is not a purely owner tenure system, though, in Denmark. Can you say a little bit more about how the cooperative works in that context, if it's also rental or primarily or entirely rental?

Anna Granath Hansson 21:52

It's more like a rental housing unit, but every housing entity, it's its own body, legally and financially. All the inhabitants come together in an association where they run this cooperative together. So they decide on the financing and on what is supposed to happen in the house together.

Paavo Monkkonen 22:14

But as I understand it, these are mostly cost rental systems in Denmark, where the people aren't owning the units, they're just paying rents.

Anna Granath Hansson 22:23

They invest a small sum, let's say, and then they are allowed to rent the apartment. I think this community aspect is really important, that it's not a normal rental where you don't have to speak to your neighbors, but in these projects you really decide things together and you need to cooperate, and usually that comes also with social activities.

Shane Phillips 22:47

I think it might have been for Denmark you wrote that something like 2% of the development cost of the project is contributed by the tenants who are going to be moving into the units.

Anna Granath Hansson 22:56

Yeah. In Swedish cooperative housing, those amounts are much larger, but in this model, a lot of people can do that.

Shane Phillips 23:05

You mentioned that private developers who own their land may be required by a municipality to transfer a part of it to a non-profit housing organization. I'm curious how that works in practice. Is it similar to how France requires developers to sell a share of their units to social housing providers? Is there compensation for this like there is in France, or is this just an expectation from the outset that you're going to set aside some share, but we're not going to pay you for it, essentially?

Anna Granath Hansson 23:34

They transfer the land directly and they get paid for it, but the payment might be very different in different projects. We shouldn't go into that pricing model because it's quite complicated, but then the non-profit housing organizations actually build the project themselves, so it's a matter of land transfer.

Shane Phillips 23:54

Yeah. Yeah. Maybe once we've talked about all three countries, we might want to come back to the role of municipal land ownership, because I think it plays a huge role here in a way that, of course, it can't really in the US because so little land is publicly owned in most of our cities.

Paavo Monkkonen 24:10

Well, and municipal land development to a greater extent, right? So the ability of a municipal government to take over some land and then lease it to the non-profit housing association or give it to the ... I mean, it's the kind of thing that we don't really do.

Anna Granath Hansson 24:24

And here we can see the difference between Norway and Denmark and Sweden. In Norway, they don't own any land, so they have limited possibilities to steer development.

Shane Phillips 24:35

Well, coming back to social mix a little bit, you note that Denmark's inclusionary housing policy is more about mixed tenure than affordability and how that goal can come into conflict with affordability because it's accomplished by reducing the number of affordable units in vulnerable areas. So can you just say more about that? Because I feel like it really highlights where the priorities lie with inclusionary housing in Denmark.

Anna Granath Hansson 24:58

Yeah. Inclusionary housing is used to incorporate affordable housing in new developments that tend to be too expensive for many people. However, the level of subsidies still makes the created affordable housing too expensive for very many people. And that's one side of it. And then you should know that the planning law amendments that were made to introduce inclusionary housing also contains a prohibition to build social housing in vulnerable areas. Because instead, a policy strives to create tenure mix in these areas as part of a plan to desegregate them.

Paavo Monkkonen 25:34

We cannot let Denmark off the hook with their so-called ghetto law of 2018. It's part of that. Yeah. This is an extreme take on integrated neighborhoods.

Anna Granath Hansson 25:45

So they just tear down social housing and then build ownership housing instead. In that way, the number of affordable units are reduced.

Paavo Monkkonen 25:55

Yeah. That's pretty controversial. And I think I was looking, there's a group of residents has taken it to the EU court that I saw September 30th, I think it will be heard. So maybe by the time people listen to this, we'll know more. We can post a link to the EU court decision on the ghetto law.

Anna Granath Hansson 26:14

We're very curious because Sweden, some people want to do the same.

Paavo Monkkonen 26:17

Yeah. I mean, it's in a lot of, I mean, in countries where they build huge social housing estates like France is doing a lot on transforming what were formerly areas of 100% social housing. I think France is doing a pretty good job. They do remove some housing units, demolish some housing units, but I don't think they replace them with market rate units. And I think they do it now. I mean, after more than 20 years of learning how to do this in a less destructive way, they're doing it in a pretty thoughtful way.

Anna Granath Hansson 26:45

Yeah. I think you have to learn how to do it correctly and not just kick people out, but actually provide them with something new.

Paavo Monkkonen 26:54

Yeah. Yeah.

Shane Phillips 26:55

Yeah. The US should have been learning as far back as the fifties and sixties with urban renewal, but I'm not sure even now we fully learned that lesson. I mean, I'm trying to think what would be an equivalent of this. I guess this is sort of a version of urban renewal and blight.

Paavo Monkkonen 27:13

It's more like hope six, I think where it's public housing estates being renewed. Yeah. I guess just- Renewed in quotes.

Shane Phillips 27:20

Rather than, I'm thinking of this in Denmark as like entire neighborhoods being off limits. Is that accurate? Or is it more like how in the US it's just, you know, they're targeting specifically public housing communities, which are usually going to be no more than several hundred units total, or maybe a couple thousand or something, but not a whole neighborhood that's just like, this is a vulnerable area. No new social housing is going to be built here at all.

Anna Granath Hansson 27:44

In Denmark it's these housing estates that were built in the Swedish equivalent of the million homes program, large scale serial housing with only social housing units. Got it. So very, very many apartments in one place.

Shane Phillips 28:01

Yeah. And I'll just note that in the outcome section on Denmark, this has not been adopted very widely. It has not produced a whole lot of affordable units thus far. The planning act was adopted in 2015 and you write that within the 45 local plans with nonprofit requirements, 10,400 new homes were built as of spring 2021, so about six years. And of these 635 are nonprofit units or 6%. So not a ton of units built out of this program nationwide. So how about the system in Sweden? Who does it serve? How is it regulated? How is it financially or otherwise supported by cities or the state?

Anna Granath Hansson 28:39

So in Sweden, inclusionary housing is implemented through municipal land allocation and often on leasehold land and the selection of developers is then based on who offers the best concept in terms of rents, housing quality, and sometimes also other social features. And land leases are based on market price of land for rental housing. So there is no direct subsidy for this kind of affordable housing. Instead there are incentives for developers, for example, larger lots of land or density bonuses. And as municipal testing is not a standard mode of operation, other selection criteria are used. Sometimes tenants are chosen by social services and sometimes they use just waiting lists, but often there is a mix of time on waiting lists and certain degrees of vulnerability. For example, families with many children that live in overcrowded housing. It's quite different to the Danish policy.

Shane Phillips 29:40

A couple of follow-up questions on this. So you mentioned that often the land is a leasehold, so the city will maintain or retain ownership of it. So what happens at the end of the lease? Do they then own the building as well or how does that work?

Anna Granath Hansson 29:56

No. Sweden has a long tradition of granting leasehold land, especially Stockholm, which has been doing so for 150 years already, and they never take the buildings back. They just prolong the lease.

Shane Phillips 30:10

Okay. Have they renegotiated every some decades or years?

Anna Granath Hansson 30:15

Yes, and decades. And at times there have been large quarrels about how to renegotiate the lease itself, I could imagine, yeah, when it has been the same for 40 years. And of course, it's a much shock when, when it has to be renegotiated.

Shane Phillips 30:32

Yeah. And how about the affordability, the price of these units, whether for rent or for sale, relative to market rate? Because you're saying there's not a lot of financial subsidies. Maybe you're getting free or inexpensive land or density bonuses, that kind of thing. How much more affordable are these units than market rate?

Anna Granath Hansson 30:50

Yeah. So let's say there are no market rate grants in Sweden. First of all. Negotiated. Good starting point. Such regulated. But we can come back to that later, but when they do these programs, they're really pushing for low rents. So maybe half of what you see in other new housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 31:13

And so have there been, maybe you could tell us about an example of one of these projects. So the municipality of Stockholm, for example, will get some land and they'll say to developers, hey, we want you to do this with some inclusionary component, compete and propose something. And then they decide and negotiate or how does, how does it work?

Anna Granath Hansson 31:35

Okay. This is fascinating. Let's talk about Örebro, the city of Örebro instead of Stockholm, because Stockholm isn't very good at this. You don't have to put that on the recording. But I think that the only really successful inclusionary housing project in Sweden was done by the city of Örebro. It was the fifth, I think, fifth largest town of Sweden. And then they asked private developers to come up with a concept where they would house certain vulnerable groups, they didn't say which, and they asked them to, it was really a negotiation process. First, the developers submitted a proposal for what they wanted to do on this land. And then they negotiated with the municipality what would be needed to really reach the rent levels that the municipality wanted to see. And then they got larger, lots of land also to build other types of housing, like market rate ownership housing as well, and other rental housing that's more profitable. And they got a density bonus and they also got to be involved in the discussions of who would actually live in the flats when they were finished. And in the end, they created the few apartments that went to families with many children.

Paavo Monkkonen 32:57

And then would these be run by a municipal housing corporation or would they be run by the developer?

Anna Granath Hansson 33:02

No, they stay in the ownership of the developer.

Paavo Monkkonen 33:05

Okay, interesting. Since you mentioned different municipalities taking advantage of this more than others, I mean, I'm curious whether you have any insight into why some cities would choose to be more aggressive on this. That's one thing that struck me. A lot of municipalities in Europe are much more proactive on housing development and on things like subsidized housing development in a way that in the US is not really the case.

Anna Granath Hansson 33:30

One thing is how large problems do they have to house people. And usually they look then at people that are the responsibility of the municipality under the Social Act, Social Services Act. And then it's, of course, a matter of how proactive politicians are, how interested they are in doing this. And then I think that in the larger cities where land prices are really, really high, it's much more difficult to do this efficiently in the Swedish system since it's so difficult to prioritize people you cannot really – it's more controversial, let's say, to prioritize others.

Paavo Monkkonen 34:09

And I guess Stockholm doesn't own a ton of land like Helsinki does. I stayed in one of the new development areas in Helsinki, which was pretty mixed in terms of housing development types, but it was like former port-owned land by the city government. So it's a lot easier.

Anna Granath Hansson 34:23

Yeah. But Sweden and Finland have a common history here. So actually Stockholm owns 70% to 80% of all land that is developed for housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 34:34

So why aren't they doing better on this?

Anna Granath Hansson 34:35

Yeah. And I think the combination of a planning monopoly and owning most of the land, it would be so easy to do something if they wanted.

Paavo Monkkonen 34:45

And is the temptation to lease it for more money just too great for them or –

Anna Granath Hansson 34:51

Yeah. And they also sell a lot of land. And when you see the calculations, how much money taxpayers lose when they convert ownership plots to even just to rental, not even affordable rental, and you see the amounts of money, then you can understand that they are hesitant to do that. Because of course this money can be used for schools, elderly care, and many other things that are also really highly prioritized.

Paavo Monkkonen 35:19

Right. Okay. Interesting.

Shane Phillips 35:21

And in some ways probably easier for many people to benefit from simultaneously, whereas each housing unit, only one person or household can move in there and without means testing, you don't even know that it's someone who really needs it compared to other folks. So I can understand the tension there for sure. Yeah, exactly. Can you talk about how – you corrected me on this already – but how the inclusionary policies interact with Sweden's rental laws and collective bargaining of rents by the Tenants' Union? I think even beyond that, it's pretty interesting how – I'll just call them market rate units for lack of a better phrase – but how market rate unit rents are regulated separately for their first 15 years and how inclusionary housing functions sort of as the inverse of that policy. The way market rate units are regulated there actually reminds me of how some U.S. states now apply rent stabilization policies, basically exempting new projects for their first 15 or 20 years before the rent restrictions actually kick in.

Anna Granath Hansson 36:20

So let's start by saying that Swedish rent setting is extremely complicated. There was a doctoral thesis written about it. It was 700 pages, so if you don't understand what I say, don't worry. But I shall try to explain. So with some exceptions, rents are collectively bargained in Sweden between the Tenants' Unions and property owners. However, to stimulate new construction, new-built rents are handed separately for the first 15 years and then they are gradually brought into the system. And this is done to allow for cost covers, otherwise we wouldn't have any new construction because the negotiated rents are usually, let's say, lower than we suppose that market rents would be. Therefore, there is no system to tailor rents to single projects, but you have to fit everything into the system, which can be difficult when you want to do something new.

Paavo Monkkonen 37:18

So the rents are negotiated into like a formula. So a unit of a certain age, of a certain size, of a certain location should have this rent rather than this building's rent is X. Okay. And this is done at the municipal level or at a larger scale?

Anna Granath Hansson 37:35

No, the municipality isn't involved at all. It's done by the Tenants' Union and the property owners. And this creates some difficulties when it comes to inclusionary housing policy, because then the municipality doesn't have control, so they don't know if they give the land, they cannot control what will happen to rents.

Paavo Monkkonen 37:54

In 15 years, right.

Shane Phillips 37:56

Do the rents vary by location? Are higher rents allowed in Stockholm than in other places? Are higher rents allowed in the more desirable or more central parts of Stockholm relative to other parts?

Anna Granath Hansson 38:09

And this is an ongoing process, let's say. It hasn't been the focus for very long, so there isn't really this nice location factor that is implemented everywhere. Instead, you can see great variation when it comes to the importance of location.

Shane Phillips 38:25

I think the variation does make sense, but yeah, there's some amount of maybe conflict with the universalism, but maybe sort of inevitable to some extent.

Anna Granath Hansson 38:34

Yeah, but I think previously, cost cover was the main focus, but now location is becoming increasingly important.

Shane Phillips 38:44

Okay, well, we'll move on to our last stop, which is Norway. And here there is a much stronger emphasis on home ownership than in Denmark and Sweden, and that seems to be reflected in their inclusionary policy as well. So what's the story there?

Anna Granath Hansson 38:59

So Norway stands out in a North European context as housing policy is focused on that everybody should be able to own their home. And a spying home has become increasingly expensive and more and more people can't afford it. Some developers have started to offer rent to buy or shared ownership schemes to widen their customer base. However, these models have met with some legal and planning hurdles in the Norwegian context, and therefore there has been intense lobbying by developers to make politicians act on this and make the necessary changes. In general, these models are very well received, and the city of Oslo is cooperating with private developers and investing to increase numbers. And the main target group of these models are mid-income groups that can now buy apartments in more central locations where most of development takes place.

Shane Phillips 39:54

Yeah, and you mentioned where the development takes place. Norway's compact city policy seems like an interesting wrinkle on its housing policy generally and inclusionary policy in particular. You write in the article that virtually all new build housing in Norway is in central areas and those are among the most expensive places to live. On the one hand, with some of those units sold at below market prices, that gives some lower or maybe primarily middle income households access to neighborhoods they might not be able to access otherwise. On the other hand, it seems like if you're not one of those lucky ones who get into one of those units, you don't have many other choices, perhaps, for new housing anyway, because the market rate units are going to be very expensive due to their location. Do you have a sense for how the policy affects people's choices in Norway for good or ill or both? I like to think that we could meet most or all of our housing needs in US cities by building almost exclusively in the urban core where land values and demand is highest, but I'm not sure anywhere here has actually tested the theory as ambitiously as Norway seems to be doing. We still rely pretty heavily on sprawling outward to meet a lot of our housing need.

Anna Granath Hansson 41:06

Yeah, I think most new housing is built in attractive locations, so if you do not get anything there, you can also opt to buy something less expensive or larger in less central locations and with good public transportation networks, it's not so bad, let's say. And it's also important to say that this inclusionary housing units are not subsidized, but that the buyer will at the end pay full market price. And it's just possible to buy something more expensive at an earlier point in time when you do not have to pay the full price upfront.

Paavo Monkkonen 41:40

Deferred purchase.

Shane Phillips 41:42

I think that's helpful context. So maybe you can explain a little bit more about how rent-to-own works and how shared ownership works, what those two programs really mean.

Anna Granath Hansson 41:51

Yeah, rent-to-buy is basically you start by renting your flat and then gradually you pay more and more and in the end you might still be a tenant or you will buy the whole department. In the shared ownership scheme, it's always the final goal that you should buy the whole flat. So during like 10 years, perhaps you co-own with the developer and then gradually you step up your ownership, but you participate in the cooperative or housing association as if you were a full owner, so you're replacing the developer as the front face of that department.

Shane Phillips 42:33

I think in the shared ownership, you said that at the outset when the buyer purchases the home, they might only be purchasing 50% of the value, 50 to 90% I think is the figure you gave. So the remainder is owned by the developer and eventually I guess they're bought out in some way.

Anna Granath Hansson 42:51

Yeah, so in the shared ownership scheme, it's really you have a plan for how you gradually buy the full ownership right of the apartment.

Paavo Monkkonen 43:01

So why would the developer want to do that? To sell apartments. Because they become a lender to some extent as well, right?

Anna Granath Hansson 43:09

Yes. And that's a complication that they want politicians to do something about and create investment vehicles that can buy out these apartments because they don't want to own them long term.

Paavo Monkkonen 43:20

Right. And is there something wrong with the mortgage market such that this has come to exist rather than banks doing the lending part?

Anna Granath Hansson 43:29

I think it's a problem with the pricing. They have two expensive products for their markets. Some companies sell as much as 40% of their apartments with this type of scheme.

Paavo Monkkonen 43:41

Interesting. And is it because restrictions on mortgage lending are very tight? No. Okay.

Shane Phillips 43:48

It's just a lot to buy upfront I guess. So say you are a home buyer who gets into a home splitting half and half. You're upfront paying half the cost of the home and half the value is retained by the developer. How do you transition over time into full ownership? Is it something where you're sort of just expected you're going to make more money and can get a larger mortgage at some point? Or is it you've built up some equity and can do something with that? How does this actually play out?

Anna Granath Hansson 44:17

This is an interesting question because originally these concepts were created for younger persons who were supposed to get higher and higher salaries. But when they started to sell these apartments, they realized that there was a demand from all sorts of people, single parents, pensioners, all sorts of even families were asking for this. But it's unknown how they analyze their customers if they check their economy or if they just say that, okay, you got the loan from the bank, then we're satisfied and they sell the apartments to them. I think the banks have had great difficulties in understanding these models. So it has not been so easy for developers to implement them because the banks have to lend both to the construction and the association that owns the building and to the future semi-owners. It has not been easy to do this new model and understand it.

Paavo Monkkonen 45:19

And so I guess this one goes maybe the farthest from what you would think about when you think about an inclusionary housing policy in that it's developers thinking of a way to get people to buy their units more creatively and then those just happen to be people with less money than…

Anna Granath Hansson 45:35

The question is even if this is an inclusionary housing at all, but since the municipalities are supporting it and they don't have any other real options because in Oslo they are trying to develop a third sector with cooperative housing and public rental housing, but it's really a pilot project.

Paavo Monkkonen 45:57

I see.

Anna Granath Hansson 45:58

So they don't have any alternatives.

Paavo Monkkonen 46:01

And how do the municipalities support these projects in Norway?

Anna Granath Hansson 46:04

Politically through prioritizing and making room for them in the different areas.

Shane Phillips 46:11

Yeah, it does seem like there's sort of a spectrum here where to the extent any of these are inclusionary housing policies, I think Denmark's is clearly the most. Land is being set aside for nonprofit housing providers and they're actually able to target lower income people or specific groups to some extent. Then you move into Sweden where there is policy support for these kinds of things and even land and that kind of thing, but the targeting is not nearly so oriented toward lower income people or you're not really able to means test at all for the most part. And then we get to Norway where it's not even really a policy necessarily. It's just developers are trying to find a market and it's just very expensive and maybe not enough people can afford it. So they're trying to… I saw something similar like this in the US where during COVID and inflation and all these things over the past few years, a lot of the really big home builders have been creating their own special financing options with buy downs and low rates and things like that, but it's only for a few years. It's sort of an adjustable rate mortgage like we had prior to the global financial crisis and housing crash here, but maybe there's a little bit more of a reasonable expectation that rates will come down and people will be able to refinance to something a little more affordable and permanent, a fixed rate for 30 years instead of just this short term thing. I think to call this inclusionary housing, I do feel like is a stretch. It's trying to help certain people who might not get into this housing otherwise, but it's certainly not going to be something available to lower income households, presumably, right?

Anna Granath Hansson 47:50

The interesting thing is that the cooperative moment and their developers have been the front runners in the Norwegian policy and also in similar schemes in Sweden. They have this reputation of being more responsible than other developers and really thinking about the customer, taking care of them, and that has made politicians listen. That's something you should ... It's about the whole housing market, how it's set up and who is saying what, so you can have different outcomes, I think.

Shane Phillips 48:25

One thing that stood out to me here is that these plannings all seemed very discretionary. The same standards don't necessarily apply to all projects and affordability requirements are often negotiated to bring a project to feasibility and that negotiation happens at the project level. I'm curious if you have a sense for how those negotiations are handled from the public sector side. Rightly or wrongly, I feel like here in the US, we often have very little faith that our municipal officials will negotiate a fair deal on behalf of the public, that they'll be taken advantage of somehow by developers or even that they'll act corruptly and collude with them. If those concerns come up at all in these Scandinavian countries, how are they addressed or is there just more faith in state capacity in these places?

Anna Granath Hansson 49:13

I would say that larger cities in Scandinavia, that's the place where inclusionary housing is mainly implemented, are very skilled in getting what they want from developers. They have the planning monopoly and, of course, in Sweden, they also – this is especially pronounced as they also own the majority of the land that is developed for housing. But also, on the other hand, when municipalities own the land, they have their own interests and maybe they didn't want to lose that much money by selling all the land or leasing all the land at lower rates because they lose money. There we have that problem instead.

Shane Phillips 49:53

Yeah, it seems like there's a real tension there where releasing more land will kind of cheapen its value, for one thing, which might hurt them in some ways from a budgetary perspective. But by not doing that, you might be limiting how much housing is built and contributing to the housing affordability challenge more generally.

Anna Granath Hansson 50:15

To sum up, I would say that if you have a planning monopoly and almost all the land, you can do whatever you want. But there also has to be efficient allocation systems so that you see that the money that you lose in doing that also does its trick. And if you're not confident in that, then you won't do anything.

Paavo Monkkonen 50:37

I think you alluded to this before, but maybe one other difference is municipal governments have more responsibilities in these countries than they do in the US, where they're basically just doing planning and police and fire, for the most part, and there you're doing a lot of social services as well. So the trade-offs maybe are more real.

Anna Granath Hansson 50:55

Yeah. And I think that when municipalities see that social services get very costly because there is homelessness or difficulties to gain access to the housing market, that then municipalities have to act under the law. And when they see that that costs a lot of money, they might do something on housing policy that at least is a cheaper solution. So that's a really strong incentive to actually act. I wish our cities would do that, but they seem not to do it.

Shane Phillips 51:26

That seems like a really important thing to call out that a lot of the social services that are provided in the US are paid for by the county or by the state or by the federal government. Rarely do these services originate or the funding for them originate at the city level, but that's where the land use policy is dictated. And so there's a real misalignment there. All right, so we have gotten pretty far into the weeds with this conversation, as we often do, but to wrap up, I want to zoom out a bit. In the previous episode, which at the time we are doing this interview is not out yet, I shared how I think inclusionary housing is in some ways what cities are left with when they give up on adequately funding affordable housing when it's not enough of a societal priority to actually pay for it. So we try to get developers to do it instead. I know that's a little bit of a pessimistic view, but I'm interested where this may have strengths compared to publicly funded affordable housing, or if you think the two approaches might be complimentary in some ways. To give these Scandinavian programs their due, it seems like these countries still have a pretty strong commitment to incentivizing developers to build these mixed income projects, including in some cases at least providing them with subsidies or early special financing. To my knowledge, the only city in the United States that pays for these units in inclusionary programs is Portland, Oregon, and that is a pretty recent development. We also talked about the importance of social mix at the top of the episode, and I'm curious if inclusionary programs have made a significant impact there. So how do you think about the future of IZ in these countries or in other parts of Europe? How would you like to see them evolve? And thinking about what we've talked about so far and the limited reach of IZ, I'm also just curious to hear about the importance of demand side programs, rent assistance, other things that maybe Scandinavian countries are a lot more ambitious with than we are here in the US.

Anna Granath Hansson 53:27

Yeah. That's a huge question. So let's start some basics. You can take it bit by bit. Yeah. So basically housing costs a lot to build and is sometimes a risky business. So the idea that investment and risk could be shared between public and private entities to potentially increase the number of new housing units, it's not so surprising in a Scandinavian context. However, we should remember that inclusionary housing policy in Scandinavia has produced really meager results and there's still a lot of hurdles to overcome for it to gain momentum. And now we also see a downturn in the market, which makes them even more difficult to implement. And in parallel, we see a left-wing cry out for more public housing and subsidies, not unlike the discussions that resulted in the assignment of the new EU commissioner for housing. So there is reason to believe that these two ways of increasing affordable housing supply, inclusionary housing policies on the one side and public or publicly supported housing are on the other side, will complement each other also in the future. And I think also for a long time, housing policy has not been even near to the top priorities of Scandinavian politicians, but in recent years there has been a shift where at least the larger cities are increasingly interested in the issue, where Denmark and Copenhagen stands out, I should say. And we clearly need more of crisis awareness for affordable housing policies to play a role. And we also potentially need to renegotiate some of the ways we select future residents to make inclusionary housing models more efficient in targeting the less well-off and really create the outcomes that we aim at in terms of social mix and affordability. Otherwise, I don't think that these models will survive. It's also interesting to note that the new EU commissioner for housing is a Danish citizen. So, it's Dan Jorgensen. So, we'll see what comes out of that.

Paavo Monkkonen 55:35

That's very interesting. I mean, the housing assistance stuff matters a lot, but I was going to say one additional difference may be, we call it inclusionary zoning often when it's not really a zoning program, especially in the United States, it's a housing program. And I think thinking about something that would be actually inclusionary zoning in the spirit of ending exclusionary zoning would be like these planning systems where you say, okay, you're going to do this development area, some of that new development should be social housing so that it can be a mixed neighborhood. And I think one other big difference between the California context and Scandinavia is that we just have such a segregated land use system between single and multifamily housing such that new affordable units in multifamily buildings are already not in the richest neighborhoods of the city, whereas a new development area on the waterfront in Stockholm is going to be a very fancy neighborhood. And so, the social mixed dream is maybe more easy to realize in that context. How much is the housing allowance in Stockholm?

Anna Granath Hansson 56:37