Episode 77: Upzoning With Strings Attached with Jacob Krimmel and Maxence Valentin

Episode Summary: Changing zoning rules to allow taller and denser buildings may cause land values to go up, and public officials may try to “capture” this added value by requiring affordable units in new developments. But what happens when costs and benefits are out of balance? Seattle offers a cautionary tale.

Abstract: This article analyzes the effects of a major municipal residential land use reform on new home construction and developer behavior. It examines Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, which relaxed zoning regulations while encouraging affordable housing construction in 33 neighborhoods in 2017 and 2019. The reforms allowed for more dense new development, or “upzoning,” but they also required developers to either reserve some units of each project at below market rates or pay into a citywide affordable housing fund. Using a difference-in-differences estimation comparing areas the reforms affected versus those not affected, the authors show that new construction fell in the upzoned, affordability-mandated census blocks. The quasi-experimental border design finds strong evidence of developers strategically siting projects away from MHA-zoned plots—despite their upzoning—and instead to nearby blocks and parcels not subject to the program’s affordability requirements. Lowrise multifamily and mixed-use development drive these effects. The findings speak to the mixed results of allowing for more density while simultaneously mandating affordable housing for the same project.

Show notes:

- Krimmel, J., & Wang, B. (2023). Upzoning With Strings Attached: Evidence From Seattle’s Affordable Housing Mandate. Cityscape, 25(2), 257-278.

- City of Seattle webpage for the Mandatory Housing Affordability program.

- Lebret, D., Liu, C., & Valentin, M. (2024). Carrot and Stick Zoning. UEA 13th European Meeting.

- Manville, M., & Osman, T. (2017). Motivations for Growth Revolts: Discretion and pretext as sources of development conflict. City & Community, 16(1), 66-85.

- Phillips, S. (2022). Building Up the” Zoning Buffer”: Using Broad Upzones to Increase Housing Capacity Without Increasing Land Values. UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

- “Although the ill effects of tightening land use controls are well established, far less practical knowledge is available on how to ameliorate the situation. It is not clear to academics or policymakers exactly how existing zoning codes and regulations should be changed to spur new construction where housing shortages are most acute; nor is it straightforward to enact such reforms, even if consensus existed … A key challenge facing policymakers seeking to boost supply and lower housing costs, in the long run, is finding a suite of reforms that are politically feasible in the short run. For example, although agreement is widespread among economists that allowing more dense construction will, in theory, boost supply and bring down prices, voters and politicians remain wary. A prominent concern is that upzoning leads only to constructing expensive units that would not directly alleviate affordability issues among rent-burdened existing residents. However, empirical evidence on the effects of upzoning is scarce, mainly because these policy changes are rare, especially at larger geographic scales.”

- “This article analyzes Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) reform, one of the largest citywide density and affordable housing reforms in the United States. Seattle presents an ideal setting to answer the question of how to tackle housing shortfalls and affordability issues. The city’s population has boomed, and house prices have soared in recent years. Although the metropolitan area population has grown 30 percent during the past 2 decades, Seattle is building fewer new units per year than when it had 1 million fewer inhabitants. As a result, since 2000, median house prices have nearly tripled; one in seven residents is severely rent burdened. Although a growing political will is for large-scale housing reform, much of Seattle’s land remains zoned only for detached single-family residences.”

- “The MHA reform presents a case study of how one high-cost city struck a balance between its efforts to alleviate affordability issues and local political opposition from both single-family homeowners resistant to change and rent-burdened households fearing displacement. The MHA program upzoned 33 noncontiguous neighborhoods between 2017 and 2019. In these areas, MHA allowed for greater density while mandating that all new commercial and multifamily residential construction contributes to affordable housing. The reform combines two policy levers that some economists consider to conflict with one another: Increasing development capacity through upzoning and requiring private development to create income-restricted affordable housing.”

- “Seattle is one of the first large cities to adopt this “upzoning with strings attached” model, a prominent policy vehicle being discussed across the county. Thus, Seattle’s MHA represents an interesting example for other cities considering density reforms to alleviate affordability issues. Whether (and when) such a policy would spur or stifle housing development, especially affordable housing development, remains an empirical question. What is the “right mix” of sticks (requiring affordability contribution) and carrots (allowing more development capacity and density) for the developers?”

- “Seattle has experienced an intensifying housing affordability crisis during the past 2 decades, driven in part by the growth of big technology companies like Microsoft Corporation and Amazon. com, Inc., which have boosted labor demand and, therefore, housing demand. The median home price has tripled since 2000, and rental rates for a one-bedroom have increased 35 percent during the past 5 years. Also, a large racial gap exists in rent burdens: 35 percent of the city’s African- American renter households are severely rent burdened compared with 19 percent of White renter households. Seattle’s population grew 15.7 percent between July 2010 and July 2016, faster than almost any other large city in the country.”

- “The MHA reform allows for greater building heights and higher floor area ratio (FAR) limits in designated MHA zones. It also requires a developer contribution in exchange for the density bonus. The contribution comes in two forms that the developer could choose: “Payment” or “performance.” Payment, a one-time monetary payment based on a predetermined schedule, goes directly into the city’s affordable housing fund; performance requires developers to build rent- and income-restricted units on site. The contributions are designed to mitigate the perceived negative effects of new development … The program generated $68 million (and roughly 850 affordable units) in its first full year in 2020, with most developers taking the payment option.”

- “One key thing to note is that this MHA program is not an unexpected “shock.” Two years of community engagement and policy analysis informed the program’s details … In fact, the current program is an expansion of the city’s preexisting voluntary Incentive Zoning program. The biggest difference from Incentive Zoning to MHA was that it became mandatory in designated geographies, in that it applies to all new permits issued within MHA zones after the reform. MHA was initially rolled out in 6 “urban villages” between 2015 and 2017 before being expanded on the same terms citywide in an additional 27 urban villages in April 2019.6 This article uses April 2019 as the “post” period, because the overwhelming majority of neighborhoods affected and permits issued occurred after this wave of the reform … The architects of MHA intended to spur the most housing production in areas with a low risk of displacement and high access to opportunity.”

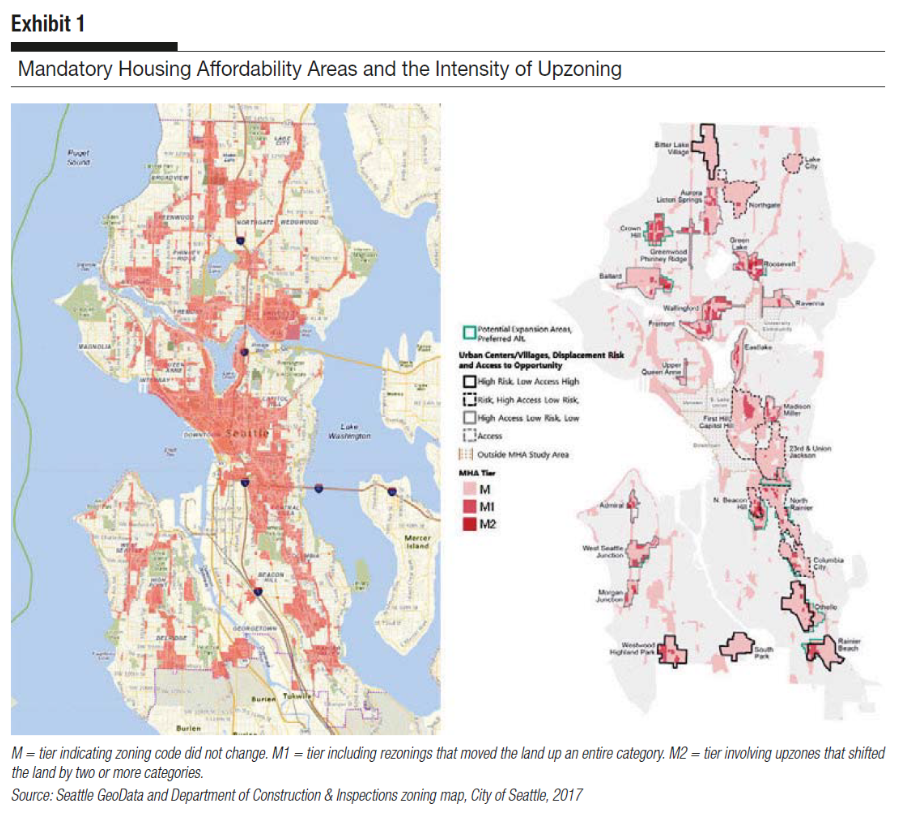

- “Exhibit 1 shows that MHA rezonings affect quite a wide geography of neighborhoods. The left panel of exhibit 1 shows all MHA rezonings. The right panel breaks the rezoning down into three tiers based on the intensity of the zoning change. In the majority of cases, called the “M tier,” the zoning code did not change, but taller buildings or higher FAR, or both, were allowed. A suffix was added to the zoning code after MHA took effect for these cases. For example, a lowrise 3, or LR3, becomes LR3(M). These rezones allow for roughly one story of additional development capacity. As a percentage of developable land in MHA rezoned areas, 78 percent of land falls under this mild change. The other 22 percent of land falls under M1 and M2 tiers, providing for more significant changes than the M tier.9 The right panel shows the three color shadings corresponding to the three tiers. The most moderate M tier is the lightest shade. Housing officials carefully choose to map M tiers, opposed to M1 or M2 tiers, in high-risk or low-opportunity areas to minimize displacement risk and avoid hurting access to opportunity. The aim was to ensure that affordable units were added in lowrise multifamily zones rather than allowing for highrise luxury apartments. However, this modest upzoning, paired with MHA’s affordability mandate, did leave M-tier areas at particular risk of lower supply responses.”

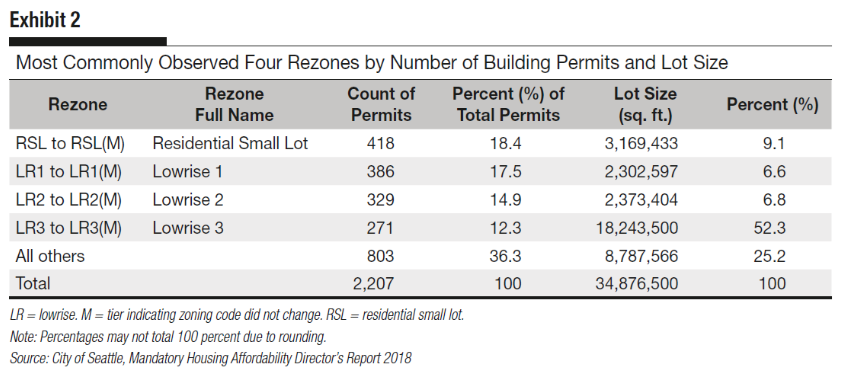

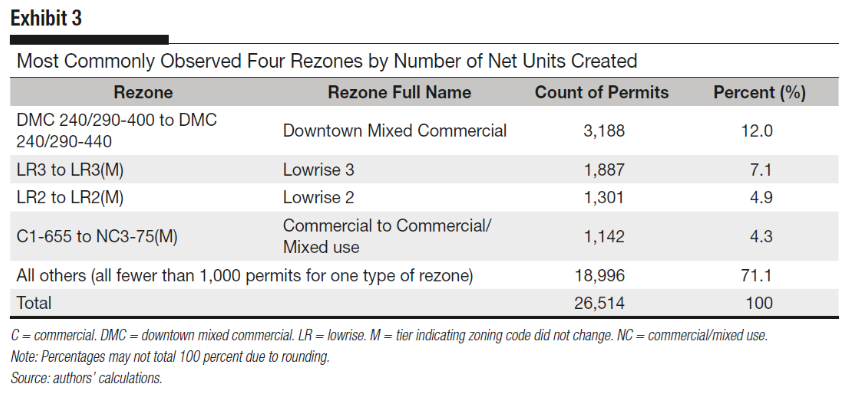

- “To understand the size of the MHA rezoning treatment effect, this article looks at the actual permitting activities following MHA rezones. At the permit level, 75 percent of all permits issued in MHA-rezoned areas between April 2019 and July 2022 occurred in areas subject to the four most common zoning changes. Exhibit 2 summarizes these four changes. These four types of rezoning were also the most common when ranked by the total square footage of the lots on which new buildings were permitted, although their ranking differed across the two measures. For example, although the fourth largest number of permits were issued in places that changed from the LR3 zone to LR3(M), those permits accounted for the largest area on which new development occurred. Of all 34 million square feet of MHA-rezoned land on which new development occurred, 52.3 percent belongs to one rezone of LR3 to LR3(M).”

- “Exhibit 3 shows the four types of rezoning in which the largest number of net units were created. Here, a partial overlap exists with the earlier set, but certain commercial areas also appear due to the permitting of especially large developments in these areas.”

- “The key takeaway is that the increased development capacity that most MHA rezonings created was relatively limited. Hence the “carrots” for developers—the development capacity increase— might not be big enough to outweigh their costs from the affordability payment or performance requirement.10 The allowable FAR increases from 2.0 to 2.2 after MHA took effect, which means the height limit increases from 40 to 50 feet, adding another floor. Other zoning code changes generally enjoy similar magnitude as LR3 does.”

- “With a relatively modest density bonus, the “affordability tax” on developers is comparatively high. Housing officials estimate that the legislation will result in 17,000 more total housing units for 20 years than would be generated by development in its absence; 5,600 of those would be rent- and income-restricted units. Importantly, estimates operated on the assumption that one- half of developers would choose to build affordable units on site, and one-half would choose to contribute to the affordable housing fund. However, in the first year that MHA was in full swing, an overwhelming majority of developers (98 percent) chose the payment option. This response suggests either that the performance option constitutes a large “affordability tax” on the developers or that the payment option levels were set too low.”

- “To examine the effect of the MHA reforms on new home permitting and construction, two publicly available maps from Seattle GeoData (part of Open Data Seattle) are merged: the map of Residential Building Permits Issued and Final since 1990 and the city’s MHA Zones map. The permit data are address-level geocoded and include information on the development site, permitting stage, plans for units created and demolished (by unit type), and other geographic data.”

- “Then a panel dataset is constructed at the census block level over time. MHA zones do not always perfectly overlap with census block polygons, so a census block is categorized as an MHA block if at least 50 percent of its area falls within an MHA zone. Under this definition, only 11 percent (3,960 out of 35,279) of census blocks are within the MHA. MHA zones account for a very small share of census blocks, but many more blocks are geographically proximate to an MHA zone. Although slightly more than 1 in 10 census blocks has at least 50 percent of its area in an MHA zone, more than 31 percent are within a census tract that overlaps with an MHA zone somewhere within its boundaries.”

- “Exhibit 4 presents population and socioeconomic summary statistics. The first three columns are block groups that were completely rezoned under MHA, those partially rezoned under MHA, and those that are fully non-MHA.13 These block groups correspond roughly to the preexisting-built environment of Seattle neighborhoods, with MHA zones being in the most densely developed areas. The summary statistics change monotonically across all socioeconomic variables. Moving from the fully MHA block groups to fully non-MHA ones, people are fewer, housing units are fewer, incomes are higher, poverty is lower, and the percentage of owner-occupied housing is higher.”

- “Fully non-MHA block groups are not a suitable control group for fully MHA block groups. As such, analysis is limited to the partial MHA block groups, which are defined as “border” MHA blocks for identification. One drawback of the border analysis is that although fully MHA block groups (column 1) do not have an adequate non-MHA comparison, these areas saw the most intense upzoning (the M1 and M2 zones). In effect, the ‘treatment’ is stronger in areas that lack a good control group and weaker in areas where an adequate control exists.”

- “Consider two hypothetical outcomes of the policy change. The “first best” outcome is an increase in overall supply in the MHA zones. With the mandatory affordability requirements, this increase in overall supply also means an increase in affordable units. At the other extreme, if the reform is not designed correctly, the change in developer incentives could deter new construction both inside and outside MHA zones. The success of MHA rests on developers’ response to a cost-benefit tradeoff.”

- “The main empirical finding suggests that developers behaved strategically after the reform took effect, which this tradeoff guides.14 In particular, while housing production did not decline overall, there was strong strategic substitution of new construction away from MHA zones. This policy outcome can be considered a middle ground between the initial hypothetical outcomes: MHA enactment did not halt all new development, but new units were not built where intended.”

- “A difference-in-differences regression is estimated at the census block level to quantify the substitution effect. Exhibits 5 through 7 show the generalized difference-in-differences result on different dependent variables. Estimates for key coefficient b3 are on the first row … Exhibits 5 through 7 tables are organized in six columns. The first three columns use the sample of all census tracts, with no fixed effects (column 1), tract fixed effects (column 2), and year-month and block fixed effects (column 3). To get to the causal effect of MHA, the analysis is limited to a quasi-experimental sample in columns 4 through 6 for estimating equation 1.16 In particular, the sample of “Border Tracts,” is used, which are tracts that straddle an MHA boundary. This sample eliminates tracts that are entirely within MHA zones and entirely outside of MHA zones. A total 397 tracts exist, and 118 are border tracts by this study’s definition.”

- “If the MHA upzoning program worked as hypothesized, much more permitting activity would transpire, and more new supply would exist in the upzoned blocks within a border tract. However, the opposite occurs—the development is happening more in blocks not upzoned within the same neighborhood … The analysis finds quantitatively strong and consistent empirical evidence for substitution of supply away from MHA zones. Across all specifications on all three quantity-dependent variables, the number of permits and the number of units permitted per month decreases in MHA blocks after the reform takes effect.”

- “The three variables that measure quantity response are whether a permit was issued at all (exhibit 5), the number of permits issued (exhibit 6), and the net units permitted (exhibit 7). These three exhibits examine housing supply activity in Seattle’s census blocks from 5 years prior to Mandatory Housing Affordability through the most recent data (April 2022).”

- “The estimate of -.004 on “Post X MHA” is very consistent across all specifications and the two geographic samples. The magnitude is economically meaningful. It is twice as large as the dependent variable mean in the full sample of all tracts (the first three columns).17 Interestingly, as the analysis moves to the finer geography of border tracts, the (absolute) magnitudes are bigger, which suggests that the substitution action is happening in the border tracts. That is, permitting activity is switching within and not across neighborhoods. Notice also that the dependent variable means an increase from 0.002 in columns 1 through 3 (the all tracts sample) to 0.007 in columns 4 through 6 (the border tract sample). One could interpret this increase as an annual likelihood of receiving a permit increasing from 2.4 percent overall to 8.4 percent for border-MHA neighborhoods, indicating that throughout this period (including 5 years before MHA), much more housing is permitted in these MHA-border neighborhoods than in either fully non-MHA or fully MHA areas. These results are consistent with developers deciding first to build in a certain neighborhood, then strategically choosing to build on parcels in that neighborhood not subject to the MHA’s affordability requirements.”

- “Exhibit 6 looks at the number of permits issued, again finding a reduction driven by MHA rezonings. The magnitudes are small (-0.007 per month), but the base is also very small (0.003), so economically, the effect is quite large. Columns 1 and 2 show that MHA blocks generally see more permitting activity throughout the sample period. Column 3 adds block and month-fixed effects, and the point estimate is unchanged, meaning that permitting differentially decreases in MHA zones. The final column limits the sample only to those census tracts that at least partially intersect an MHA zone. Because tracts are much larger than blocks, this specification removes all control census blocks that are far from an MHA zone, thus potentially differing unobservably from treatment areas. The point estimate is unchanged and even a bit stronger, but it remains statistically significant. The overall permitting activity tended to move across MHA boundaries after the policy took effect. The results for the number of new units created is very similar and robust.”

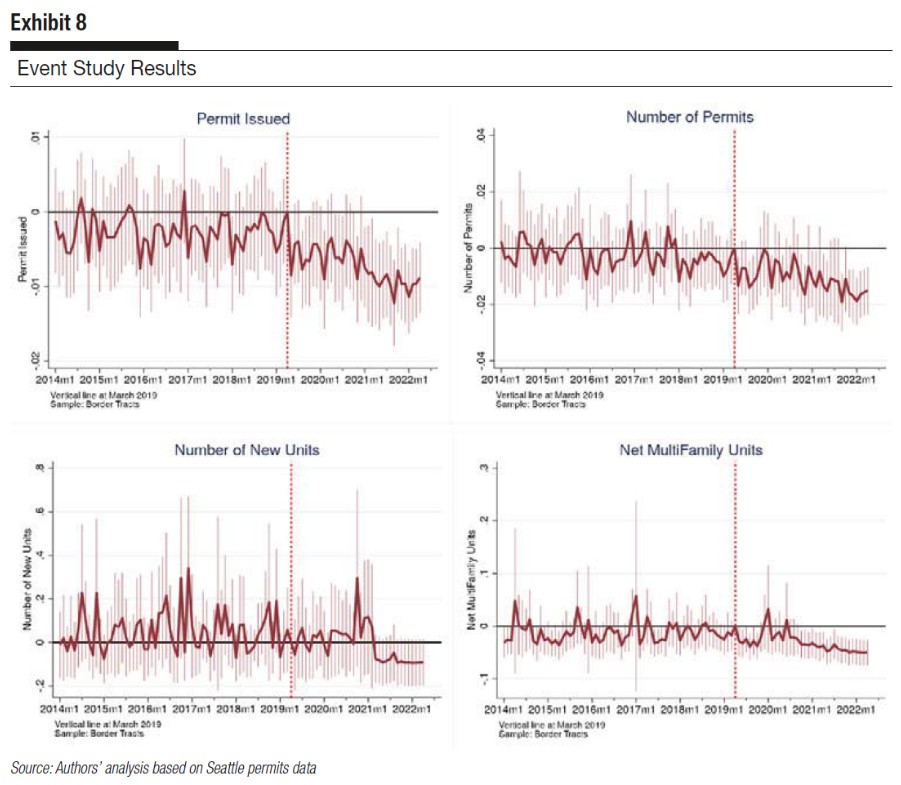

- “The four event study plots use the three variables previously discussed and the net change in multifamily units to illustrate these findings visually (exhibit 8) … These plots show that MHA enactment in April 2019 was associated with a lower likelihood of permit issuance in MHA zones (top left), fewer permits being issued per block (top right), slightly fewer units permitted overall (bottom left), and significantly fewer multifamily units permitted (bottom right). This final result of fewer multifamily units is particularly worrying, considering that a major goal of MHA was to encourage dense multifamily development.”

- “However, several caveats must be mentioned. First, the program is in its infancy. These data allow for examining only the first 3 years of MHA, 2 years of which were affected by COVID-19. The pandemic likely negatively affected both the demand for multifamily housing and the speed of the city’s housing permitting process. It may also have shifted the demand for housing across Seattle’s geography, given changing patterns of working from home—and here in Seattle, perhaps for the 5 to 10 years or even longer. Certainly, policymakers did not account for the pandemic in their initial efforts to pair the amount of MHA’s upzoning with the number of its affordability requirements.”

- “Second, the MHA border block design has drawbacks. By design, MHA blocks near the border were zoned for smaller increases in density than areas farther away from an MHA boundary. This design necessitates a tradeoff between examining where the reform’s treatment is more powerful (the interior, fully MHA neighborhoods) versus where its effects can be more precisely estimated (the border, partial MHA neighborhoods). In choosing the latter, the authors acknowledge that the estimates are potentially downward biased; MHA’s effects may be more positive in the interior areas.”

- “Third, MHA may have large noneconomic or difficult-to-quantify benefits. For example, given the size of the reform and the consensus it took to implement it, MHA has provided Seattle a potential springboard to expand upzoning in magnitude and geography—one that policymakers hope to use. These benefits may be institutional or political in nature. Although such institutional and political benefits are outside the scope of this economic analysis, they may be quite significant.”

Shane Phillips 0:05

Hello! This is the UCLA Housing Voice podcast, and I'm your host, Shane Phillips. This week, we're joined by Jacob Krimmel and Maxence Valentin to discuss something referred to as "upzoning with strings attached," "carrot and stick zoning," or perhaps just a modern form of "value capture." The government changes what you can build on a parcel, but to take advantage of those changes, developers have to offer something in return. It has become a ubiquitous practice in planning departments across North America, and I would argue, not entirely without merit, but it also has unintended consequences that don't always receive the attention they deserve. So we're giving them some attention.

We're doing so through the lens of Seattle's Mandatory Housing Affordability program, which modestly upzoned multifamily neighborhoods across the city at the same time that it instituted inclusionary requirements, meaning developers had to either include below-market units in their projects, or pay a fee. The ideal outcome of a policy like this is for developers to build more affordable and market-rate housing. But that is not what happened in Seattle, and we're going to talk about why that is and what lessons it holds for other cities.

As a reminder, in Fall 2025, UCLA will be kicking off a full-time 11-month Master's in Real Estate Development (MRED) program, and applications will be open until January 15. True to form for the Luskin School of Public Affairs, this will be a unique program with a holistic approach to development and urban change. If you're currently working in real estate and looking to move up or coming from a different field and interested in learning the skills needed to work as a developer, check out their website at luskin.ucla.edu/mred, andconsider applying before the January deadline.

The Housing Voice podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, with production support from Claudia Bustamante and Gavin Carlson. As always, you can reach me with show ideas, comments, or questions at shanephillips@ucla.edu. With that, let's get to our conversation with Jake and Max.

Jacob Krimmel is an economist at the Federal Reserve Board, and Maxence alentin is a postdoctoral researcher at ETH Zurich, and we are talking with them about the practice of relaxing zoning restrictions on new development in exchange for community benefits of one kind or another, especially for including affordable, below-market units in their projects. Jacob and Maxence, thanks for joining us, and welcome to the Housing Voice podcast.

Jacob Krimmel 2:53

Thanks very much for having me.

Maxence Valentin 2:55

Thank you very much.

Shane Phillips 2:56

And my co-host today is Mike Manville. Hey Mike.

Michael Manville 2:59

Hey everybody. Good to be here.

Shane Phillips 3:01

So first things first, we always ask our guests for a tour of a city they know and want to share with our audience. We have double the guests, so we will get double the tours today. Jake, how about we start with you?

Jacob Krimmel 3:12

Oh, sounds good. Okay, so I would like to give you all a quick tour of my hometown of Baltimore, and since it is summer in Baltimore, we're going to be focused on two things that the city does really well, which is seafood and Orioles games, as a big baseball fan myself. So I think we'd probably start the tour in Baltimore's Fells Point neighborhood. It's on the water, as it sounds. Ad I didn't look this up before, but you know, you have to take my poetic license, word for it, in saying that Baltimore has more miles of coastline than any other city on the East Coast. We're going to say that that's true for purposes of this anecdote. So Fells Points is a beautiful neighborhood on the water. Tons of great row houses, cobblestone streets. This one, I think, is true. It actually does have the most pubs per capita in the US, ina square mile basis I guess I should stay. So that's a great place to start. Grab a beer, grab some really nice, cheap, fresh oysters from the Chesapeake. Walk around the neighborhood, and then make our way to the inner harbor via the National Aquarium in Baltimore. From there, keep walking down Pratt Street until you get to Oriole Park at Camden Yards. I think, you know, I'm biased, but I think the one of the most beautiful baseball parks. But even more broadly, one of the best places to to watch a sporting event in general, in the US. The the vibes are immaculate. It's a beautiful stadium. I guess it's about 30 years old at this point, but it's designed to look like something that was, you know, built 115 years ago, with all the nice modernity... amenities as well. So before the game, hang out outside, you know, soak in the atmosphere. See the Baltimore Orioles hopefully win. And then after that, we'll probably take a cab or an Uber up to a nice restaurant in Hamden or Woodbury, which is sort of an old mill neighborhood. So you really get the sense that this place is built on the water, but also relying on old industry that was coming the rivers that feed into the bay there. So I think you get a nice feel for the history, the landscape, and also the industries that were there and the ones that are there still to this day.

Shane Phillips 5:21

I heard Baltimorioles there, was that intentional?

Jacob Krimmel 5:25

I guess it's kind of just once I, if you ever go back to, you know, your hometown, you kind of have your old accent comes back that you didn't know that you had. There's a lot of sort of swallowing. It's not Baltimore, it's Baldumore. You kind of just -- it gets sucked up.

Michael Manville 5:40

Baltimorioles is more efficient. It's on brand for you as an economist too.

Shane Phillips 5:51

If you can be one thing, be efficient. Max. How about you?

Maxence Valentin 5:54

I'll do like Jake and bring you to my hometown, which is on the other side of the pond. So I come from a city that is about 30 minutes by train from Paris on the northeast side of Paris. It's a city called Meaux, M, E, A, U, X. It's about, depending on what village you count in the agglomeration, it's about 80,000 to 100,000 inhabitants, so somehow very small yet very close to Paris. It's quite rural, and so you don't really feel in a big agglomeration, even though a lot of people go there every day to work. And if you were going there, I'll definitely bring you to the city center. So we have a medieval city center with a very big cathedral there, and a hidden place that a lot of people don't know, there is a very beautiful garden at the back of the cathedral that is an enclosed garden -- enclosed by the walls of the medieval town. So it's very, very pretty. Definitely walk around, get a coffee and lunch somewhere. And then I would definitely advise you to go to the museum of World War One. So if I'm not mistaken, I think it's the largest museum dedicated to World War One. That opened about 10 years ago, so very recent, extremely well made, gigantic. It's located there because there was a lot of battles that happened at the outskirts of the city. So definitely something I would recommend to do there and then probably do a cheese tasting. Meaux is the birthplace of the famous brie. The true brie comes from Meaux and so definitely make you try some of this before you leave. And if I may, something that I found quite interesting since I started studying cities and urban policies is something that the east part of the city experienced during my youth. They demolished completely those high rise social housing. Every year they were demolishing one of these ugly towers, one by one, and they replaced those with like, three to four story buildings, way more workable, way more amenities for the people there. So not quite gentrification, because the population has not quite changed over the last 20 years, but a complete remodeling of what the city is like and how we should have social housing and what the neighborhoods look like. So it's a very interesting case studies about how to redevelop some type of what used to be a decaying part of the city. So definitely try to pass through the through the area too.

Shane Phillips 8:28

France is definitely doing a lot of interesting stuff on social housing in particular, and just the quality of the housing as well. And of course, Paavo is in Lyon for two years because of his interest in the social housing and just housing programs there in general. It is funny to hear though about a rural area being 30 minutes from, you know, a world class urban area like Paris, because, of course, you go 30 minutes from Los Angeles or New York and you are still in Los Angeles or New York, it's barely even suburban by that point, much less rural.

Jacob Krimmel 9:01

I think he also said by train, which is not possible in a lot of U.S. places.

Maxence Valentin 9:06

Thank you, that's what I wanted to say. 30 minutes by train. I think by car, I've done it once. That doesn't take 30 minutes.

Michael Manville 9:12

If you go, we do have trains in Los Angeles, and if you go to the train station and wait 30 minutes, the train will almost arrive. You'll be on the platform.

Shane Phillips 9:16

Itwill almost arrive, almost always. All right. So for today's episode, we are covering two things, one of them, the original motivation for this conversation is a study by Jacob and his coauthor, Betty Wang, published last year in cityscape. The title of the article is upzoning with strings attached evidence from Seattle's affordable housing mandate and in it, Jacob and Betty analyzed the effects of something called the mandatory housing affordability program, which was instituted in 2017 and 2019 the MHA upzoned parcels across 33 Seattle neighborhoods. Price and as the name suggests, it also mandated that projects built on these upzone parcels include some units at below market rents, which just means affordable to low income households. Their key finding is that although the policy selectively upzoned areas designated as urban centers and urban villages, presumably with the intent of directing more growth to those central areas. The MHA had the opposite effect. Developers shifted production to parcels outside the neighborhoods where the policy applied, and they also appear to have shifted away from building multifamily housing quite as much toward relatively more expensive single family townhouse projects, we'll be discussing what they found and the conclusions that other cities and maybe Seattle itself can draw from their experience. When we reached out to Jacob, he suggested that we also invite Max, since he's been doing his own research on this subject, while there is not yet an article to share, we will refer to some slides from a presentation he gave or his colleagues gave in Copenhagen this June. The presentation is titled carrot and stick zoning, and it's a preview of some research by Max and his colleagues, Daniel Lebret and Crocker Liu. There is a link to those slides in our show notes. Their team is working on establishing a theoretical framework for this practice of upzoning with strings attached, and they are investigating some of their hypotheses by looking at a bunch of developments built under similar programs in New York City. And their theoretical framework strikes me as a good starting point for this discussion. I think most of our listeners will be familiar with the general practice of relaxing development restrictions in exchange for some kind of payment by developers. This is how a lot of cities are producing housing or capacity for new housing. Maybe that payment is an in kind payment, like providing some affordable units on site, or infrastructure improvements off site, for example. Or maybe it's just paying money into a public fund that invests in those kind of things. Or if you wanted to build housing in a few Los Angeles City Council districts in late 2010s, maybe it's putting $500,000 in a brown paper bag and giving it to the right elected official. It is not surprising that a lot of people view this practice, especially the last one, but just generally, this practice of upzoning with strings attached somewhat cynically, either as a shakedown by government or bribery by developers or both, but it does have a certain rationality within the planning system that we've constructed in most cities. So Max, could you walk us through the reasoning for that?

Maxence Valentin 12:40

Yes, of course. I think the practice you describe, we're becoming more and more familiar with this practice, not necessarily because it's new. I think this idea that developers are paying for infrastructures when they increase density is something that's been used quite oftentimes in the past, but we're becoming more and more familiar with it because cities have been encoding it and putting this in their zoning code more and more, including Seattle, including New York City and so on.

Shane Phillips 13:09

This is in contrast to negotiating project by project, but not really having formal standards or expectations.

Maxence Valentin 13:17

Yes. The big difference between discretionary zoning that I think happened more on the west side of the US versus as of right zoning. Just as an example, I think New York City tries to codify everything, and so that comes with the drawback of having a very long zoning code, but it comes with the benefits of removing the opacity that you described regarding this mechanism. And I think cities have been using this mechanism more and more and coding it in their zoning code, specifically because they recognize that they have bargaining power vis a vis the real estate developers. And this comes from two main reasons. I would say, first, there is a big increase in demand for space. So specifically housing in urban areas so massive increased demand for space. And second, land use regulation, zoning regulations are becoming more and more binding, and so these together makes that if developer wants to make large profits on a real estate development, they would rather want to have a zoning variance, or they would really like to build something that goes beyond the current regulation to make profit. So if a city is rational, they would probably say, okay, but this also comes from some of our own land use regulation action, and would like to share in this profit, which is exactly what we try to document in our paper. And so this is yet very rational on paper, but some cities might have pushed the stick a bit too much, and I think the case that Jake is going to discuss a bit later, but theater is a great example for it is that if you don't design the proper balance between the carrots and the sticks, you might end up with failure of these initial policies. Which I think is good, that Jake's and all the people have been documented.

Jacob Krimmel 15:03

Or at least unintended consequences. You know, they think this is a long, a long, long game, but I think we have, I think, unintended consequences before we jump into declaring something a success or a failure. But yes, I think that's the on the right track. Yeah, yeah.

Shane Phillips 15:16

So when a city up zones A parcel, especially at the request of a developer, they're creating, unlocking somehow increasing the value of that land very significantly. And there's a feeling that for one you know, why can't we share in that? But also, if we don't share in that, it's just a windfall to the developer, right? And so we may want them to actually build the thing that we're allowing them to build, but we would rather direct that windfall towards some kind of public benefit, like affordable housing, rather than just, you know, dump it into their pockets. So that leads me to this critique you often hear, which is that upzonings create these windfalls that primarily benefit developers, that they're a developer giveaway. You hear that, especially among opponents of upzoning, but it's also a concern I think we've all heard raised by people who are generally supportive of allowing denser and more affordable housing types. But it really depends on what kind of upzoning you're doing. Right? Can you talk about the distinction between rezoning at the request of a developer and upzoning as a matter of policy across much wider area,

Maxence Valentin 16:23

yes, of course, but maybe I'll give you a tiny nuance of what you just said. Sure, I think when we we discuss profit for the developers, I think there is also the city, if a developer builds, we get more housing units, regardless if they are below market rent of their market trend. And I think if we have the goal of stimulating real estate developments, we should not see real estate developers that make profits as necessarily a negative outcome if we wish to increase density and the number of units.

Shane Phillips 16:56

Well, I do think that distinction is important. I mean, I want to drill down on that a little bit, because I'm certainly not opposed to developers profiting. I recognize that if they don't, they are not going to build things just like pretty much any other business. But there's a difference between, you know, buying land at a price based on the cost of construction, based on rents, based on sale prices. That you can expect maybe a 10% 12% 15% return on your investment versus you buy that land, you apply for a variance, the value goes way up, and now your profits are 20, 30% on cost or whatever. And like, you actually didn't need that level of profit to motivate building housing. And so I think that's the concern some people have, that. It's sort of just a loss for the public, because the developer would have built the thing at 15% profit, and we've given them much more.

Maxence Valentin 17:47

No, no, absolutely. But it also, there is also probability that the change in zoning happens in 10 years from now, and not two that he has planned. And that is a risk that is bearing.

Shane Phillips 18:01

And this is why discretion is just not a great approach generally, because people actually have to be compensated for taking that risk when you don't know what's going to happen.

Maxence Valentin 18:09

Yes, and I think that's something we try to document, is that there is a trade off that developers face, and they have constraint, financial constraint that you described, but also physical constraint. And unless we understand their constraint and their trade offs, and if a city has the goal of stimulating real estate development, which really needs to take those constraints into account when they design policies.

Michael Manville 18:31

I mean, the other thing about this is that all of this critique assumes that it sort of implicitly assumes there's no benefit to the public when the developer builds the housing right. Because you say, like, oh my gosh, you know, we let this developer build more housing. Developer build more housing and make some money, and we got nothing at all. So well, presumably someone's going to live in this housing. And most of the cities that do this have shortages of housing, and so there actually is a public benefit to someone building housing units. And now you could say, oh, well, what if the developer just sits on the land and doesn't build on it. Well, sure, that's too bad, but the way these zoning ordinances are designed is that that doesn't trigger an affordable housing mandate. The Affordable Housing mandate is triggered when the developer goes to deliver what is, in fact, a public benefit, which is more housing units. This is a little off of what Jake's paper is about, which is a little bit narrower, but, I mean, I think it's important to recognize, from my perspective, at least, that there's like, building housing is a public benefit. Like, it's a weird position to say the public gets nothing when someone puts up an apartment building, because people will live in the apartment building.

Shane Phillips 19:34

Yeah, yeah, no. And I agree with that, and I think, but this is my point, is, I think even people who agree with that, like myself, recognize that when housing capacity is constrained and you change it in a very kind of focused nature, at a parcel level, on a single street, that kind of thing, you are creating, unlocking a lot of value, and you can, in almost all cases, if you are thoughtful and careful, you can capture. Back a lot of that, and not only get the new project, but get some kind of other benefits in addition to it. And so it's just sort of leaving money on the table. And that's, that's more my point, yeah.

Michael Manville 20:11

I mean, I guess I'm gonna, I'm gonna channel my inner Hayek and say, you can't. I mean, it's just like, you know, you think you can, and you think you can pull all these levers, and it's just, how do you know what the person needs? Like, quote, unquote, you didn't need this, and now I'm going to step in and mess with it. Yeah, and I think Jake's paper is evidence of this. It's like, it's sure, conceivably, you could get this right, but it's, it's pretty easy to get it wrong. And if you actually think housing is important, you know, then, then I think we should approach this with some caution.

Shane Phillips 20:42

Yeah, yeah, 100%.

Jacob Krimmel 20:43

I think Max would probably say another way to potentially get this wrong, though, is to not codify anything and to leave it completely discretionary and idiosyncratic, and that may result in even further uncertainty and more administrative burden, yeah, and that sort of thing too. So I think yes, there's definitely lots of ways to get it wrong or to not quite have the right mix if you codify it. But Max might argue, if you don't, you're not even attempting to evoke the public private partnerships that his paper is about.

Maxence Valentin 21:12

That's right, plus you increase the opacity. And I think the public perception you described earlier, Shane, that there is negative public perceptions about this mechanism is also because of its opacity and leaving it completely discretionary also increase this negative public perception, and I think cities trying to codify it is also to reduce this opacity. It comes with some drawbacks. It's easy to get it wrong, but it comes with benefits too. Yeah, yeah.

Shane Phillips 21:40

A certain Mike Manville, on this very podcast, has a very good study about this with Tanner Osman about the negative perceptions. Yeah. I

Michael Manville 21:48

mean, it definitely in California, it has fomented a lot of distrust of the entire regulatory process. And so I just to clarify, I completely agree with that, that I don't think the solution to the problems of codification of these bargains are, is to just have them happen on ad hoc basis. I think that there should be few of these bargains like I guess, and this, I realize this, we're a long way from this politically. Is just, if you realize that housing prices are very expensive in your city and you have an eight story height limit, and developers could build 12 stories, you should just say, Build 12 stories, no trade.

Shane Phillips 22:22

And this is a quite good transition, I think. So there are two very important conditions that you need to meet for upzoning with strings attached to work. One is that the upzoning has to actually increase the value of the land, and the other is that the land value gained from upzoning has to meet or exceed the cost of the additional requirements that you're imposing on the projects. If upzoning doesn't increase the value of the land, then there is no value for you to capture. So any strings you attach are likely to decrease the feasibility and odds of redevelopment below what they were even before the upzoning. I don't think we will have time to get into it today. We've already been talking about this a lot, but I do talk about the circumstances in which upzoning might not increase land values in my broad upzoning white paper from 2022 which is in the show notes, the second condition, though, that at least as much value is gained from upzoning as is lost from the additional requirements. That really brings us to Jake and Betty's study of the mandatory housing affordability program in Seattle. We'll get into this balancing of sticks and carrots more later, Jake, but let's start with a bit of context on what motivated the MHA and how it was designed. First, just what were the outcomes that Seattle's urban planners, policymakers, elected officials were after with the creation of the MHA, and kind of to Mike's point, how did the city's political environment help shape the program into what it actually became? Right?

Jacob Krimmel 23:49

So this is a complicated answer, but I think sort of a familiar story or familiar setting in that, like many cities, Seattle, and by the way, this is the timing of the reform we're talking about is, you know, 2017 to 2019 but Seattle's, I guess, dual housing crisis or housing affordability crisis, had been brewing for, you know, the better part of two decades before that, like, like many cities, right? So I would basically describe the city as facing two interrelated crises. And one is just a shortage of housing full stop. And I think in large part this probably comes from, in Seattle's case, the booming of the tech sector. There just the increase for demand for housing, because people could make quite a good living there. And the second crisis is just housing affordability, especially for low and moderate income families. So it's both a shortage overall, which is pushing average prices up, and also you have increased income inequality in general. And of course, the people who are initially lower in modern income are going to be, you know, even further strained as renters, especially so. What Seattle did was to try to address both of these crises, sort of with one ambitious policy reform, which was a large scale upzoning with a mandatory inclusionary zoning component. It, and I'll define what those mean in a second for in case that wasn't clear. But I guess the the way to think about this is it's kind of like a killing two birds with one stone approach. Importantly, when I say large scale upzoning, I mean this really at a large geographic scale. So Seattle up zoned over 30 neighborhoods like large, large portions of the city center, especially neighborhoods that were already zoned for dense, multi family housing, whether or not it went high rises or not, it was just these are the sorts of neighborhoods you should be thinking of that were further up zoned or densified. So it was a very far and wide upzoning, not necessarily an intense upzoning. So think of this as a policy that affects space horizontally more than vertically, which I think is really important when we think about exactly why it's so tricky, and why the option value of some of these neighborhoods and parcels was not increased to a significant enough degree that Shane was referring to. So you know, like I mentioned, they're trying to increase housing production, especially in low and moderate income areas that were already quite dense and built out and places that are near transit. So this is really a well meaning and I think well designed and well targeted policy in these in this cases, you know, the policymakers wanted to upzone places that were already in very high demand, that had seen high increases in rents. So it makes sense to try to increase production there, as opposed to other places, and also to try to incent developers to provide some units that are at or below market rate as well, with respect to sort of the second part of your question about the political environment that I guess, birthed this grand bargain and I'm using air quotes, since this is an audio only podcast, but I'm using grand bargain and air quotes because this is actually what the group of policymakers called it. And they weren't just official policymakers, per se that helped to craft this large reform. It was a group of about a dozen or two dozen developers, lots of land use lawyers, planners, city officials, local activists and advocates and researchers as well. And so they called this sort of thing the Grand Bargain, because it was attempting to be a something for everyone policy reform. Now we'll talk about later, about why something for everyone? What's the, what's the old phrase about a compromise? You guys can fill in the blank, you know, everyone's equally unhappy, or something like that. I think that's potentially an apt description of what happened here, but it was something that, because it was this grand bargain allowed them to lay the groundwork for potentially future reforms too. So the folks who were very concerned with affordability and displacement via gentrification and things like that, they got their affordability mandate. That's something that developers could not opt out of. They could only opt away from. And we'll talk about exactly what opting away from is probably later on, and the folks that were really concerned about increasing supply, sort of at all costs, and this wasn't just developers. This is researchers and academic community from University of Washington, for example, and other city officials as well that were sort of, you know, less stuck on affordability mandates. They got their their upzoning as well to try to increase housing production in these areas that were so in demand. So hopefully, that sort of laid the groundwork for exactly what the MHA was after and how it came to be with this, this grand bargain and this sort of dual mandate, if you will. And speaking of which, one thing I should mention, everything I'm talking about right now is, is are my views alone and not of those of the Federal Reserve? And maybe we should sneak that into the beginning of the podcast that

Michael Manville 28:27

was masterfully I like the way that the dual mandate just flowed out of you and triggered that association.

Shane Phillips 28:38

I do want to just underline here. So on the political side of things, the point, ultimately, is that there was a feeling that maybe many people would have liked to just upzone These neighborhoods, just allow more housing period, and leave it at that taller, denser, more floor area, et cetera. But they did not believe that they had enough political support amongst the various stakeholders to do that unless they attach these strings.

Jacob Krimmel 29:07

Yes, I think that's exactly right. And there's another key point too. The areas that were reformed or upzoned and then that had this affordability requirement as well were largely not single family, detached, zoned places, right? So I think Seattle only touched something like 6% of their land area that was zoned single family detached, which is the majority of the parcels, or the more jewelry area. So they're leaving a lot of potential densification on the table, and that's a political reason as well. And so yeah, there is something that's very clear. Whether or not you spoke to folks on the ground in Seattle, but you could just sort of look at it from a 30,000 foot view and say, why aren't they touching the land that's single family, detached, zoned? I think that becomes sort of a familiar we know the answer to that question. It's kind of the same reason why we have these kind of against these issues in so many other places, which is your wealthier homeowners, that folks with. Lot more, relatively more political power on a per capita basis. Probably they're the ones who are also potentially flight risks to nearby municipalities and things like that. So there's, there's definitely a sense of not wanting to upset that apple cart. And so if you're not going to touch a good majority of your land area that's zoned for residential, then you're going to have to make a lot of concessions to the incumbent households and incumbent renters who are already being priced out of the neighborhoods that they may have lived in for a very long time. And those concessions would come in the form of affordability mandates to make sure that folks could afford to rent in these places on income that's below the area median, something like that. It's telling

Shane Phillips 30:37

about where the political power really lies, that the negotiation or the compromise was not on where they build, on building, you know, some in single family areas, but rather these affordability mandates instead, but keeping everything pretty much limited to multifamily zones. So how did all of this translate into the actual design of the policy? How and where did zoning change? I guess we have a little bit of the picture of where. But how did it change? How much and what conditions were added to projects built in these MHA areas?

Jacob Krimmel 31:08

Yes. So maybe the best way to think about what the MHA did in terms of up zoning is to describe what it didn't do. We should not be thinking about an area that was Single Family Zone that all be all of a sudden, becomes multifamily zoned, right? You should not be thinking about a place that has, you know, is zoned for large multifamily apartments that have a height limit of something like 70 feet, going to a height limit of 1000 feet, or something like that. That's not the intensity that we're that we're talking about here. It's sort of the modal case. Is a low rise two to a low rise three or something like that. And what that means, in really layman's terms, is adding maybe one story of development to low rise apartments, increasing floor area ratios by a small percentage, and also sort of densifying places that allowed for small townhouses to add an additional floor or something like that. So that's sort of the intensity of the upzoning or the densification that we're talking about. Now. As far as the stick, I guess you'd say what the developers had to pay was they essentially had a choice of what the designers of the program called Pay or performance. If a developer wants to build in a mha area, they either had to pay into a centralized affordable housing fund. So that's sort of like a direct tax on development in the traditional sense. Or they could choose the performance option, which meant that they could hold a certain share of units in that development for folks who are making below the area median income, something like that. So that's that's sort of what they're up against. So in order to take advantage of building larger, higher buildings, slightly higher buildings, you'd have to keep some one of these units in reserve or pay into some centralized fund that would then be distributed for affordable housing somewhere else throughout the city.

Shane Phillips 32:54

And how large were those requirements in terms of the affordability, the pay and performance. It sounds like the performance was considerably more expensive, and a lot of developers ultimately went with the Pay option. But are we talking 15% requirement? 10% 20% of the units for low income households?

Jacob Krimmel 33:13

In most cases, it ends up being that you're thinking about a place that there's less than 10 units in these buildings to begin with, usually more like three, four and five, and then they're holding one or two. Oh, wow, in reserve, yeah. So it can be, like, essentially, a large percentage, right? Because if these buildings aren't that big to begin with, and the units themselves and the costs are quite lumpy, right? It becomes something like a one in three or a one in four, or a two and six, or two and eight, something like that. So it seemed as though, you know, the anecdotally from developers that I spoke to, it very quickly meant that, you know, things didn't quite pencil that the way that they would, and that adding, you know, an additional floor on a townhouse, if you really can only add maybe one more unit, or really, you just sort of have a different type of unit, one that's larger, right? And then you have to have one of those be below market value. The Pay option seemed more like the way to go, or alternatively, and we'll talk about the results in a second, you could sort of opt out of the area altogether and try to evade the mandate and develop on areas nearby that were not subject to the affordability requirements,

Shane Phillips 34:16

allowing one additional unit, but requiring it to be below market, which is effectively operating at a loss. Reminds me of that. Like, yeah, we lose money on every unit, but we'll make up for it in volume.

Jacob Krimmel 34:29

Yeah? So I think that that's sort of like the one of the worst case scenarios. So I will say it's sort of like, this could have gone a couple of different ways, right? You have a lot of land area that's now subject to this affordability mandate. You know, you might be concerned that new production just halts altogether in these places, despite the fact that they're super in demand and that prices in general are rising. That would certainly be like a worst case scenario. The best case scenario is that sort of you get the carrots and stick ratio correct, and that it still is like super beneficial for developers to not only build in these areas, but. Really taking advantage of this large upzoning, which, of course, I think, seemed to be in agreement that the intensity of it was not large enough, and that the option value of development did not then increase underlying land values enough to intense, intense development, despite the affordability mandate. But then you kind of have a sort of a third way, which is essentially what we found was that new construction doesn't halt in these areas, the types of homes that come onto market, change a little bit, and there's a little bit of change in where smaller units go.

Shane Phillips 35:27

Yeah, it usually ends up somewhere in that middle space. So I think from here we can move on to the study design a little bit and see how you came to the conclusions that you did, what data you needed to pull together. So you've kind of set up the what you called the first best outcome, which is the MHA program incentivizes more production, and it's more market rate and more below market rate affordable units. At the other end of the spectrum is you design the program poorly and you just get less housing overall. And your question is, where along that spectrum, did Seattle and its developers actually fall so tell us a little bit about how you did that, what data you needed to pull together and what you were looking for to actually provide evidence of one outcome or another.

Jacob Krimmel 36:14

Yeah, absolutely. You know. The question is, how do you study the effectiveness of a large scale upzoning that affects so many different places, sort of more or less all at the same time, and places that are, you know, quite different from one another. The best case scenario, the ideal experiment, we thought of Betty Wang and I'm my co author. We thought about trying to take two really similar city blocks or even parcels that are, you know, observably quite similar, one of which is exposed to the MHA affordability mandate, one of which is not, and look sort of before and after MHA takes effect, and try to see which block or which parcel saw more new home construction after the policy goes into effect. That's sort of the ideal thing to look for. And then that's going to basically motivate our study design, which to talk about in just a second. So as far as data, the great thing is, we used all public data A big thank you and kudos and Job well done to the city of Seattle for having really great open data, not just spreadsheets on housing and permitting and things like that, but also maps as well, which is super helpful. Not only that, but they have lots of other core city functions in their Open Data Program. So do check that out. At the core of our research, though, we used building permits data at the sort of the permit level, and looked over time, both before and after the MHA came into full effect, and we looked at parcels that were zoned to be subject for the MHA rezone versus those that were not subject to it. So in general, the first thing we had to check is how similar and different are these treatment or control areas? Like, is it fair to just look at all MHA areas versus all non mha? And the first thing that we discovered is that these areas in general, on average, are quite different, right? So as I mentioned, the MHA as a reform is not touching very much single family zoned land. So you don't really want to look at production going on in the wealthier neighborhoods that are all single family, that are not subject to it, versus the core city, where you're having lots of high rise apartment development. Those aren't really great treatment and control areas to look at, because it's really far from an apples to apples comparison. So what we did was we looked at census blocks and Census Block Groups, so quite small areas that are within the same census tract, and some of those blocks themselves were subject to the MHA and some were not. So I guess the way to think about this is, if you think of a census tract, there's basically a line going through it, and on one side of that boundary line, those parcels are subject to the affordability requirement and the upzoning, and the other side, there is basically no change before after. And so we're going to look, sort of within census tract, within neighborhood and see how different blocks are affected. The great thing that we saw, though, is that just 10% of census blocks in the whole city were subject to mha, but almost a third of all census blocks are in a tract with some MHA coverage. So there's lots and lots of border areas to look at, which is really cool. So by zooming in on these border areas where part of the neighborhood is subject to mha, but part of the neighborhood isn't we're making a much better apples to apples comparison in doing so, and that's going to help us sort of get a much more precise estimate on the effects of MHA on development.

Shane Phillips 39:10

Got it, I think now we can get into what you and Betty found. You looked at the odds of a permit being issued and the number of permits issued on one side of the MHA boundary or another, and this is before and after the policy went into effect. And you also looked at the number of units, so total units, but also specifically multifamily units on both sides of that boundary. We've sort of hinted at this many times, but what was the effect of the MHA program, or the effects along that spectrum, from increasing overall and affordable housing supply in MHA zones to decreasing new supply inside and outside those zones. Where did Seattle land? Right?

Jacob Krimmel 39:51

So we landed in sort of the middle of the road. Result, which is, you know, not all good, not all bad. We didn't find that development stopped altogether in these neighborhoods. So it wasn't the case. Said, even if you were near an MHA area, that developers avoided altogether. But it also wasn't the case that developers didn't respond in terms of negatively to the sticks that they were faced with. Basically, first we find that there's still a lot of permitting activity in areas that are subject to the MHA, and so that's going to hold whether we look at MHA areas that are in the city, sort of like in this the Center City, or just on parcels that are subject to the MHA in these border areas. So there is still permitting and construction activity going on. However, though, after the MHA takes effect, we see sort of a pretty sizable reduction in permitting activity in these areas, and instead an increase in permitting on nearby parcels that are not subject to the affordability requirements of MHA in the same census tract. Basically, you could think of this as strategic avoidance, or developers sort of evading the affordability mandate, but still citing their projects in these same census tracts, in these same neighborhoods that are super in demand. There's basically a couple of different ways to look at it. One conclusion is, you're still getting new home construction, new home production in neighborhoods that are in demand, where we actually need to see a lot of housing supply going but it's not going on the precise blocks that designers of the program wanted it to be. And also, in other words, you're not getting the same increase in affordable units that the folks who designed the program had hoped for. Now, with respect to the multifamily housing, there's basically a couple of different things going on, the sort of strategic avoidance or the displacement of units that's happening across these boundaries tend to be for smaller townhouse type developments. The types of buildings that we're seeing essentially disappear are these sort of three to four unit buildings and five to eight unit buildings that are not going across the boundary to the place where there's no affordability requirement, these places are more likely just not being built because of this, the affordability stick that we referred to earlier. If you have a three to four unit building and one of those units needs to be below market rate, that tends to be something that developers didn't quite pencil, and so those projects just ended up not happening altogether.

Michael Manville 41:57

I mean that that makes a lot of sense, and it's honestly, I'm pretty surprised Seattle included developments that small. The typical iz ordinance in the country usually starts at somewhere closer to 10 units, for exactly that reason. So it was very ambitious of them to apply it to developments that are of that small a size. Yeah.

Jacob Krimmel 42:19

Yeah. We thought so too. And then that's sort of the the mandatory aspect of it. And we could get into more discussion later, and I'm interested to hear your your all thoughts on the pros and cons of doing an mha. M stands for mandatory, right, right? So mandatory housing affordability means that if you want to build in this area on this block, then there's no way out. You either have to pay or perform. Of course, the outside option, then, is to go to, as we found a nearby block that's not subject to this right

Maxence Valentin 42:46

in New York City, you can not use the bonus far and still construct a 10 FAO and not use the bonuses and not provide the social housing. So you can opt out, even though you're within what they call the MIH zone. So I'm surprised that Seattle could mandate a strong mandate on this.

Jacob Krimmel 43:08

Yeah, that's right, there was a strong mandate on this. There's no at least as far as I know, they haven't changed it, and certainly the timeframe of our study, it was mandatory. Now we could talk about ways to tweak this policy. One thing would be to do exactly that, and maybe it's easier to once you have this policy set up with the mandatory to remove that restriction, than it might be maybe to do the opposite. So that could be maybe one benefit of this sort of design moving forward.

Shane Phillips 43:33

It does seem like I don't know, maybe Hindsight is 2020 but it seems like it should have been obvious that the bonuses were too small relative to the affordability requirements that you would run into this like lumpy problem, where a 10% affordability requirement on a four unit project is effectively a 25% requirement, where the in lieu fees were set too low. So almost all developers went that path. Did you hear from planners, or, I don't want to be too critical here. But did you hear from planners or anyone in Seattle about why this happened, why they went forward with this specific mix of carrots and sticks, when I sure there were people warning them at the time that this was not going to do what they intended, or at least was going to have some unintended consequences.

Jacob Krimmel 44:18

So we heard from some people that knew that it was doomed to not work out quite as intended. I think it is an open question of what is the right level if you're going to go with this specific design, then you're sort of arguing about numbers or about setting the Pay option to be at the correct level. I think that they clearly set the Pay option too low. But at the same time, it didn't make sense for smaller projects to have this essentially like one for three or one for four requirement, either.

Maxence Valentin 44:45

But there's also the time frame question. I mean, did they enact this so that 30 years from now, every building has one unit below market? I mean, you study very quickly, so it's a very quick effect that you're documenting. But. Maybe the plan was a 30 year plan. I'm just asking. 30

Shane Phillips 45:03

years from now, the deed restrictions probably expire in the market. Yeah, I don't know. I might be wrong. Some cities have longer restriction periods. California, it's 55 years generally. But you can't plan too far in the future.

Michael Manville 45:19

I mean, I don't know the specifics of what happened in Seattle, but I will say that in general, there's a there's a combination of factors that sometimes lead to things like this occurring. One is that people just tend to, or a subset of people just tend to think of developers as, you know, enormous fat cats, which is, I think, something that some developers that reinforce that. And so there's just this idea that, well, they're bursting with money, that they're making so much money, of course, they can manage this. And then, coupled with that, is everybody has, everybody who's worked in a local government at all has encountered a situation where a developer sort of cries Wolf, you know, legislative, a piece of legislation is introduced, a developer shows up and says, no one will build anything like I'm going to have to sell my land, and I'm moving at the Cayman Islands or whatever. And then they put the regulation in place, and the guy goes and does exactly what it was going to do. And I think if you remember those instances, you can draw the sort of logical, but not quite correct conclusion, well, that any regulation that a developer objects to, they're just crying wolf. I mean, I still find it surprising, just because cities are notorious for just copying other cities and following sort of best practices. And if you just looked around at iz across the country, there's very few places that combine mandatory iz with such small development sizes, but that may contribute to what was going on. Yeah,

Jacob Krimmel 46:42

I think I'm thinking back to some of the conversations we had now. Oh my gosh. It's been almost two years at this point. It definitely seemed like a very fraught when we spoke to folks, it seemed everyone was on better terms. They had already struck this grand bargain. But when they were recalling how the policy process was made, it seemed like very fraught relationships on every side, a lot of animosity to our developers, a lot of distrust of the local community members who everyone thought the other one was acting sort of in bad faith. So I think that kind of is how we landed where we did. But I think it is sort of baby steps towards densification is the charitable way I think, to look at it. And also, one lesson that folks talked about in Seattle a lot was that getting everyone to the table to the table to agree on something was a success in and of itself, and sort of set up this potential for some like institutional capacity, or potential to repeat a similar type of grand bargain in the future. And again, you know, you could argue whether that's like a totally way too charitable way to view this, but I think that was something like an important piece of color to add to sort of what could be looked at as like a failure or large unintended consequence when you're looking at strictly from the perspective of a policy analysis, as we're doing so I do think it's important to think about that stuff too.

Michael Manville 47:51

I think that's a that's a great point. I don't want to dwell on it too much. I just, I will say, I to pick up on what you said. I think is very easy for situations like this to result in cities kind of painting themselves into corners because of the competing pressures they have on each other. And as you said, it's like, well, we want to not do much to most of the land because we have very sensitive voters there in the small remainder of the land. We want to generate a noticeable amount of affordability, but we want to do that without actually changing the way the neighborhood looks too much right, and that your your Venn diagram just contracts to the point where, and I'm going to sound a little bit cynical, but I think it's right, your main accomplishment was that you had a series of meetings where you got these people to agree, which I have knowing people like this firmly agree is An accomplishment. The big question is, how much of that consensus would be preserved if you then sort of touched one of those third rails, right? Like, actually, you know what, we got to go into the single family zone if this is going to, you know, we got to make this building 10 stories high, yeah. And, you know, I think there's a pretty good chance that meeting would break up, back down into animosity, but it's a, I don't think anyone should deny. I'm very critical of inclusionary zoning, but, like, I understand why cities do it, and I understand the extremely difficult political positions that people feel like they're put in. Yeah, I

Jacob Krimmel 49:10

think that's exactly right. And just to put some numbers on it, so I did look up this post dates our paper, but maybe, like, a month or two ago, they the city released, sort of, their annual report on mha. And just a few stats I'll read off is that since the adoption of the MHA, and this is through 2023 so it's, you know, there's been eight months since this happened. There's been 56 performance projects throughout the city, and that's totaling about 5000 units. So 5086 units were built. And of that total, the property owners committed to providing 400 MHA units with affordability requirements. So it goes into effect, essentially, in large scale, in 2019 so for four years, that's 400 affordable units. I'll let folks decide if they think that that's a lot or a little, or what the counterfactual would have been, right? But that's that. And then, you know, that's sort of the performance option. And then as. Far as the money that they've collected from developers is about $300 million so that's potentially sizable, and that gets sort of placed into the coffers for affordable housing projects and in other neighborhoods and things like that, right? So that's sort of the the cut and dried results of the policy writ large. And I think that those numbers are not surprising based on on our study, and we think we know that it definitely changed developer behavior, certainly on the margin. One

Shane Phillips 50:23

thing that I think a proponent of the MHA program might say, or a proponent of inclusionary zoning more generally, might say, is that the problem here was not that there weren't enough incentives for developers, but that the policy only applied to some parcels in the city. And so the argument here would be that if MHA applied everywhere, then developers couldn't strategically evade those areas, so they'd be forced to build the mixed income housing that city planners intended. What do you guys say to that argument? I

Jacob Krimmel 50:55

want to hear what you guys say before I answer.

Maxence Valentin 50:58

I think developers have always other opportunities. So if it's not within the MA, as Jake just said, when it's not in this designating area, they're going to build just outside. If the whole city of Seattle is going to be designed, they might just build outside of it, and then otherwise, they will make their return on another piece of land somewhere else in the country. So they have target returns that is somehow set by the financial sector. And so there is always other pieces of land that could be developed. It's a bit cynical, but I think that's also the way the financial market function. Yeah, I

Jacob Krimmel 51:32

think that's exactly right. Go ahead, Mike, sorry, yeah, no,

Michael Manville 51:35

no, I was gonna say I also think that's exactly right. I mean, I think that the the only situations where you don't have maybe results like that would be where, if you just said an entire residentially zoned Greenfield was going to be having inclusionary zoning, because then, you know, there's no going concern on that land that's already making the property owner some money. But like with, you know, Seattle, where most parcels already have something on them, and there's going to be neighborhoods adjacent to Seattle that are reasonable substitutes. I think you're just right back where you started, just on a bigger scale.

Shane Phillips 52:09