Episode 42: Vienna’s ‘Remarkably Stable’ Social Housing with Justin Kadi

Episode Summary: Social housing — housing built for limited or no profit, often with government support — came to account for huge portions of the housing market in many Western European countries following World War II, but its prominence has declined since the 1980s, when many governments began to shift their housing investments away from construction and toward direct financial support for renters. This shift is arguably one cause of the housing affordability crisis many cities find themselves in today, but in the face of opposing trends, two cities stand out for maintaining and even growing their social housing stock: Vienna and Helsinki. In this episode, Justin Kadi shares the history, policies, and politics that have contributed to the “remarkable stability” of these two cities’ social housing programs, and offers an incredible overview of how social housing is planned, financed, built, and operated in the places it’s been most successful.

- Kadi, J., & Lilius, J. (2022). The remarkable stability of social housing in Vienna and Helsinki: a multi-dimensional analysis. Housing Studies, 1-25.

- Eliason, M. (2021). Unlocking livable, resilient, decarbonized housing with Point Access Blocks. Larch Lab.

- Housing Voice ep. 32 with Diego Gil, on Chile’s shift toward a more neoliberal and demand-side housing policy framework

- Housing Voice ep. 28 with Chua Beng Huat, on Singapore’s highly centralized public housing program

- A brief history of “Red Vienna,” a product of the political victory of the Social Democratic Party in the early 1900s which led to tax reform and heavy public investment in housing

- Housing Voice ep. 20 with Magda Maaoui, on social housing in France

- “The declining relevance of social housing has been a key feature in Western housing systems in the last half century. Whereas in the post-war context the sector developed into a sizable part of the tenure structure in many countries, particularly in Western Europe, since the 1980s, it has been marked by erosion and decline. Alongside shifting policy priorities and economic circumstances, the sector has lost relevance vis-à-vis homeownership, and more lately, specifically in liberal market contexts, private renting. Such a development, with considerable variation in timing, speed and degree, has been observed in a wide variety of housing systems, including the UK, the US, Australia, the Netherlands, Sweden, Ireland, and Germany.”

- “To what extent social housing is really ‘a thing of the past’, remains vividly debated, however. Several authors have questioned such a conclusion, based on different grounds. Some agree that the sector has been ‘pushed further to the margins of the welfare state’ (Blackwell & Bengtsson, 2021, p. 1), but argue that the changes have not been as marked as foreseen by some observers (e.g. Harloe, 1995). Some emphasize recent changes that might require revisiting earlier conclusions (e.g. Kadi et al., 2021; Tunstall, 2021). Again others (e.g. Mundt & Amann, 2010) contend that the argument is based on a narrow geographical scope. This latter literature essentially concludes that social housing has survived to a much larger degree in some countries than in others and broad generalizations should consequently be made with caution … This paper mobilizes a comparative case study of two traditional social housing cities in two distinct national housing systems to contribute to the literature in two ways: first, it goes beyond the dominant focus on the national level in assessing the development of the sector. Second, it introduces a multi-dimensional framework for such an analysis that draws together different dimensions from the literature to assess social housing stability/decline.”

- “First, we provide a comparative case study of Vienna and Helsinki. Both cities have a long tradition of providing social housing, although the specificities of social housing provision differ considerably. Meanwhile, the cities are embedded in two radically different national housing systems, namely Austria, a corporatist-conservative system with a large rental housing stock, and Finland, a traditional homeownership system. If the type of national housing system matters for the development trajectory of social housing, as some authors have suggested (see e.g. Kohl & Sørvoll, 2021), we would expect diverging developments in the two cities. Second, we analyze our cases through a multi-dimensional framework of social housing decline/stability that we present below. In it, we draw together the above-discussed dimensions of sector size, stock privatization, new housing production, and residualization.”

- How social housing is defined in this study: “Blackwell & Bengtsson (2021, p. 2) provide a straightforward definition that allows for doing so, with social housing constituting ‘rental housing that is operated on the basis of meeting housing need and not primarily in order to make profit for the landlord’. This is general enough to apply to social housing in several contexts and also fits with the broader notion of social housing in our two cases studies.”

- “While social housing has grown and expanded across most Western European countries in the post-war period, there was considerable variety in the mechanisms of, and rationale for, the provision of the sector. In some countries, such as Sweden, the Netherlands and Austria, it was designed as a comprehensive part of the housing market, provided by non-profit and/or public authorities and targeted to a wide range of income groups. In others, such as the UK or Finland, it traditionally was more closely focused on working-class households and had a smaller target group (Ronald, 2013, p. 3). Form, finance, providers and management of the sector also differed considerably between contexts (Scanlon & Whitehead, 2014).”

- “Since the 1980s, however, policies towards the sector have tended to converge across housing systems (Harloe, 1995; Jacobs, 2019; Scanlon & Whitehead, 2014). Alongside a broader restructuring of the welfare state, housing policy more broadly, and social housing policies specifically, have come under pressure … Research has disentangled how these changes have led to a declining relevance of social housing in different Western European contexts. Doing so, authors have highlighted particularly the following four dimensions:

- “Declining sector size: a relative decline in social housing vis-à-vis other tenures, particularly home ownership, and an absolute decline of the stock due to privatization or demolition”

- “Stock privatization: a transfer of units to private owners, either through selling directly to tenants through a Right-To-Buy or en bloc sales to investors, or through a conversion of owners from former public or non-profit entities into private companies”

- “Shifting housing production: a decline in new social housing production, commonly promoted through a shift in subsidies from object-side to demand-side”

- “Residualization: a shift in the socio-economic profile of the tenure towards poorer households, either as a result of intentional policy (such as the tenure reform in the Netherlands following from an EU ruling), or as an unintended side effect of other policy decisions.”

- “In terms of definitional characteristics, there is no official, legal definition of social housing in either city. In Vienna, it is typically used as an umbrella term for two housing sectors: the council housing stock, which is owned and administered by the City of Vienna, and the limited-profit housing stock, which is administered and owned by limited-profit housing associations. Both sectors fulfil the criteria of social housing set out by Ruonavaara (2017, p. 9) in that they are not priced by the market and primarily targeted at low and middle-income households. As regards pricing, the mechanisms in the two sectors differ. Rents in limited-profit housing are cost-based and reflect the overall costs of a development project (including financing, land and construction costs). In council housing, rents are set by the City in line with federal rent regulation laws … As regards the targeting to low and middle-income households, in both sectors there are maximum income limits for new tenants. They are set at a rather high level, though, to ensure a socially-mixed sector that is not reserved for low-income households. In practice, however, the income profile is typically higher in limited profit housing. A key reason is that tenants, for most units, have to provide a downpayment to enter the sector (comprising a share of the costs for land, financing and construction). Such a downpayment requirement does not exist in council housing.”

- “In contrast to Vienna, social housing in Helsinki (as in Finland) is officially called ‘government-subsidised rental dwellings’, which in everyday language transforms to ‘subsidized housing’. It is an umbrella term that includes student housing, housing for residents with special needs, such as the elderly or physically disabled, as well as right to occupancy-housing … In this paper, we focus specifically on the segment of social housing called ARA-rental housing (excluding student housing) [ARA: The Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland, a government agency], which is social housing directed to middle- and low-income households and with this target group shares similarities with council and limited-profit housing in Vienna. Local authorities (municipalities), as in Vienna, and other public corporations are the largest owners of social housing in Finland. However, in contrast to Vienna, corporations that fulfil certain preconditions and limited liability companies of various types (but in which local or public authorities or corporations under certain preconditions have direct dominant authority) can also develop social housing (ARA, 2013/2015).”

- “There are specific rules for rent setting, set and monitored by ARA. These include capital expenditure (such as interests and amortization as well as rent of the plot) and maintenance costs (janitorial services and maintenance, water heat, cleaning of stair cases, and common spaces, waste management and property management). Part of the capital expenditure is shared among all tenants of the social housing provider – not, as is the case in Vienna’s limited-profit housing stock, shared among tenants of one housing estate … It is developed on land owned by the city, and the city subsidizes social housing by giving a reduction of the plot lease. In contrast to Vienna, there are currently no income limits for applicants or residents in social housing in Finland, but there are specific criteria for tenant selection set by ARA. Today the criteria include housing need (for example risk of becoming homeless, having limited dwelling space and living in expensive housing relative to income), wealth and income (low- and middle income applicants being understood as having a more urgent need for social housing than higher income applicants) (ARA, 2021). Social housing can be sold off, or converted into private rentals after a period of 20–45 years, which is typically the amortization period of the state subsidized loans (Table 1).”

About Vienna housing market:

- “While both Vienna and Helsinki have a long tradition of social housing provision, they are embedded in distinct housing systems. Austria is an example of a conservative-corporatist housing system with a large rental sector (Matznetter & Mundt, 2012). With a home ownership rate of some 48.8% in 2020, the country has one of the fewest home owners in Europe. Meanwhile, with some 23.5%, it has one of the highest social housing rates (Statistik Austria, 2021, p. 110). Austria has been identified as an example of a unitary or even an integrated rental market (Mundt & Amann, 2010), although the liberalization of rent regulation in the 1990s has triggered a dualization between private and social rents and thus challenged this categorization to some extent (Kadi, 2015). ”

- “Social housing is the largest sector in Vienna to date. In 2020, it accounted for some 43.3% of all units, with council housing and limited profit housing each making up about half of the stock (21.9% and 21.4%). The second largest sector are private rental units, with about 32.4%. Homeownership, predominantly in the form of flats, rather than single-family homes, accounts for some 20.4%. If we look at the size of the social housing sector over time, we can see that it decreased to some extent between 2001 and 2011 and has increased slightly in the last decade, so that it remained overall stable when 2001 and 2020 are compared (Figure 1) … The relative development conceals the stark absolute growth of social housing in the city, however. Whereas in 2001, some 302,000 units belonged to either council housing or limited-profit housing, in 2020, this had grown to around 397,000 units – an increase by 23.9% within the sector over 20 years alone. The great majority of new units came from the limited-profit housing associations. This sector grew by some 75%, from 112,000 units in 2001 to 196,000 units in 2020.”

- “Privatization has been a rather marginal phenomenon in Vienna’s social housing stock. … [L]imited-profit housing associations that used to be owned by the federal government were sold under a right-wing federal government in the early 2000s and thus some 60.000 units in Austria were privatized. … [T]here is an ongoing privatization in the limited profit housing stock through a right-to-buy … Annually, some 800 units are sold in Vienna in this way.”

- “Social housing accounts for a substantial share of new housing production in Vienna. Between 2012 and 2018, more than 60% of the units were constructed in the limited-profit housing sector (see Figure 3). This amounts to a substantial increase compared to the last two decades, when the share of social housing stood at around 40% (in the 2000s) and 30% (1990s) … Noteworthy, the share of council housing has increased from the 1990s to the 2000s, but has since then vanished. This is related to a decision by the City of Vienna to terminate new construction in the sector as of 2004 (except attic conversions and amendments of existing estates). New social housing production has subsequently been taken over by limited-profit housing associations (Kadi, 2015) … In 2015, the City announced that it will restart the council housing program and build 4,000 new units until 2025 (Wiener Wohnen, 2019).”

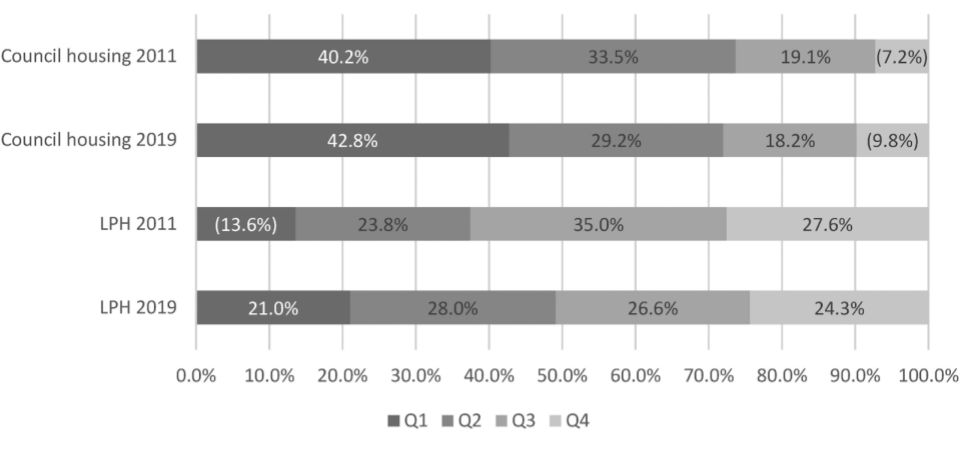

- “Residualization of social housing in Vienna has to some extent taken place, but on a rather moderate scale. One thing to consider is that both council housing and limited profit housing are traditionally very mixed socio-economically. This does not only result from the fairly large size of both sectors, but also from the rather high income limits … In 2011, some 40.2% of the tenants in council housing came from the first [lowest] income quartile. In limited-profit housing, this was clearly less, with some 14% … In both sectors, the share of residents from the first income quartile has increased, indicating a certain residualization. The dynamic is somewhat different in the two sectors however. In council housing, the first income quartile gains ground vis-a-vis the second and third income quartile, i.e. the lower and upper income middle-class. In limited-profit housing, meanwhile, all other income quartiles lose importance vis-a-vis the first quartile. What is more striking, however, is the different degree of change. In council housing, the residualization trend is much more moderate than in limited-profit housing, signalling that the process has been more important in the latter sector in the last ten years.”

About Helsinki housing market:

- “In contrast to Austria, Finland has been characterized as a homeowner society, with 62% of all households living in owner occupation in 2020 (Statistics Finland, 2021). Until the 1990s, both owner occupation and social housing construction were supported through state subsidized loans. Today homeownership is supported through tax reliefs for households with housing loans (this will end in 2023 however). Rent regulation was at work until the 1990s, when housing policies retrenched (Juntto, 1990; Ruonavaara, 2017). The rental market today is in Kemeny’s classification dualist (Bengtsson et al., 2017), with unregulated private rents and cost-based, regulated rents in social housing. Out of all apartments in Finland 7,7% are ARA social rentals, 4,9% other ARA housing, 24,7% private rentals, 11,6% other unregulated housing and 51,1% owner occupation (ARA, 2019).”

- “The homeownership rate in Helsinki is 41 percent, while some percent account for right of occupancy flats (Helsingin seudun aluesarjat, 2021). Social housing accounts for 19 percent of all housing (Asumisen ja siihen liittyvän maankäytön toteutusohjelma, 2020, pp. 22–23). The proportion of the different tenures have remained fairly stable throughout the last two decades (Figure 2). The private rental sector has grown the most after a slight decline. Homeownership has also declined by 4 percentage points after initial growth. Social housing, meanwhile, has declined by some 3 percentage points between 2002 and 2019 … Differences in the absolute development of the social housing stock are starker: whereas in Vienna, the social housing stock grew moderately in the 2000s and more quickly since then, in Helsinki, it was the other way around.”

- “Compared to Vienna, privatization has been a rather prominent phenomenon in Helsinki … In 2004 more than a third of the government subsidised rental flats (24 000) were still owned by two non-profit companies and the rest (45 000) by the City of Helsinki (Vihavainen & Kuparinen, 2006, p 17). The two largest non-profit social housing providers, Sato and VVO transformed their business strategy when rent regulation was abolished in the 1990s and became real estate investors. They have since converted and sold off most of their social housing stock. Whereas SATO still owns some social housing, VVO sold its last social housing flats in 2016.”

- “According to the current Housing Programme in Helsinki, 30 percent of all new apartments should be government subsidized rental flats. Around 8 percent of these flats should be student housing or housing for young people, and the remaining 22 percent realized as social housing or housing for special groups. Half of the new stock should be owner occupation and private rental units, predominantly flats but also single-family houses, row houses or town houses, and the rest should belong to the so-called intermediate forms such as price regulated owner occupation housing (Asumisen ja siihen liittyvän maankäytön toteutusohjelma, 2020). The City allocates plots for new social housing according to the Housing Program. The relatively high landownership of the City (64,2% in total), ensures the availability of plots.”

- “As in Vienna, there have also been attempts in Finland and Helsinki to direct social housing towards middle-income households. To have a better social mix in social housing and avoid residualization, income limits for applicants were abolished in 2008 (Hirvonen, 2010, p. 14). A follow up study in 2010 however revealed that income levels of neither residents nor applicants had increased since the implementation (Hirvonen, 2010, p. 75). Nevertheless, in 2017 the national government re-introduced income-limits, with the aim to direct social housing towards low-income households (Strategic Program of Prime Minister Juha Sipilä’s Government, 2015). A study by the City of Helsinki (Vuori & Rauniomaa, 2018) in 2018 showed that out of all tenants, only five percent, mostly single households, had incomes above the implemented income limits. The gross-income of the residents was almost 40 percent lower than that of the average income resident in Helsinki. Considering the results of the study (among other issues), the City of Helsinki and other social housing providers found the income limits unnecessary, and they were abolished in 2018 by the same government that implemented them. Today more than half of the residents in social housing owned by the City of Helsinki belong to the three lowest income groups (1., 2. and 3. decile). Two percent of the residents belong to the second highest income group (9. decile), and zero to the highest (10. decile).”

Discussion:

- “How to explain this stability? … Blackwell & Bengtsson (2021) explain the stability of social housing in Denmark vis-à-vis the cases of the UK and Sweden with two features of the Danish system: first, a ‘polycentric governance system’, in which authorities at different scalar levels exercise certain degrees of control. Changes, such as decisions to privatize, can thus not easily be pushed through (Blackwell & Bengtsson, 2021: 16). Second, a multi-layered financing system that is less reliable on central government contributions and thus also less vulnerable to cuts on this level (Blackwell & Bengtsson, 2021: 14). Both arguments are important for our cases.”

- “In Vienna, decision-making is divided between national and provincial level, with some additional room for manoeuvre for housing associations (regarding tenant selection, decision on new construction and asset management). The federal government is in charge of important legal acts (e.g. the limited-profit housing act and the Tenancy Act). Until 2018, it also collected and redistributed housing taxes to lower governmental levels (since then this is done by the provinces). At the provincial level, Vienna, decides about the specific use of housing subsidies (since 1989), is responsible for zoning and planning decisions and the management of publicly owned land. Moreover, Vienna, like other provinces, is an important owner of social housing. There was a short moment in the early 2000s where it became clear how this governance structure curtailed federal privatization plans.”

- “In Finland too, the central government is in charge of the legal acts concerning social rental housing. The Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland (ARA) steers and monitors social rental housing by, for example, granting the guarantees for loans and monitoring that the rents are cost-based. The interest subsidies, when granted, are also paid by the Housing Foundation of the State (VAR), and the government decides the threshold for when these subsides are paid (currently if interest rates rise above 1,7%). It is however the owners of social rental housing who are in charge of steering tenant selection and setting rents (according to the law). As in Austria, it is at this level of ownership where the polycentricity argument became visibly relevant. When the government in power between 2015 and 2019 suggested temporal contracts in social rental housing in cities, the City of Helsinki, the largest owner of social housing in the country, prepared plans to buy out the entire stock from the centralized system (in other words convert it to social rental housing under rules set by the City).”

- “The financing argument by Blackwell & Bengtsson (2021) is of relevance for both cases as well. In Vienna (as in Austria), the reliance of limited-profit housing associations, which are the key provider of social housing nowadays, on regular government contributions is limited. The associations get a considerable part of financing for new projects, typically around 1/3, from capital loans from special purpose housing construction banks. Other parts come from the associations’ own equity (around 10–20%) as well as from tenant downpayments. While around 1/3 typically comes from low-interest public loans, most of the funds for that (∼60%) are from loan repayments by associations to governments, minimizing the need for additional funds (Pittini et al. 2021, p. 11) … In Finland, even more, all loans to develop social rental housing are today taken from private banks. Due to the large housing stock of Helsinki, it is likely that the City could acquire a loan also without a guarantee from the central government which would give the City the possibility to develop their own social rental housing system, if necessary.”

- “While certain independence from national government in both decision making and financing is thus important, it is in fact also stability in national policy that is relevant to understand the continuities in social housing development. In Austria, the post-war consensus between Social Democrats and Conservatives over the usefulness of housing market intervention has been upheld to considerable degree also under different coalition constellations in recent decades. The high relevance of object-side subsidies in funding for housing is a striking indicator of the continued commitment to social housing in particular. In 2011, some 62.9% of housing subsidies in Austria were granted through object-side subsidies. By comparison, in Great Britain, it was 11.1% (Wieser & Mundt, 2014, p. 254). A recent pan-European study found that EU member states only spend an average of 26.1% of their housing budgets on object-side subsidies (Housing Europe, 2019, p. 28).”

- “In contrast to Austria, in Finland, broad support along the political lines (also social democrats) in terms of housing tenure has traditionally been for homeownership. The development of housing subsidies after WW II was linked to communists and left-wing parties gaining more power (Ruonavaara, 2006). However, today, there is a consensus on the need for social housing in city regions. The commitment of national government to the sector is highlighted in the so-called MAL-agreements (land use, housing, traffic) between the municipalities in the Helsinki Region and the government. The government pays a start-up grant (€10 000/social housing unit) and the current government program has the goal to increase the proportion of ARA housing in new production to at least 35 percent – substantially higher than the goal of the previous government, which stood at 25 percent. If the municipalities reach this goal, they get state support for larger infrastructure developments (Ministry of Environment, 2021b).”

- “In 2019 [in Finland], subject side subsidies accounted for more than 90 percent of housing subsides (90.8% being paid as housing allowances and 2.5% as tax relief for homeowners). In 2019, 6% of the subsidies were directed to the object side (out of which nearly half addressed housing for special groups) (Hurmeranta, 2020). Resultantly, from 2000 to 2017 the number of social housing flats decreased by 16% in the whole country, while private rental grew by 50% (ARA, 2019). Despite this, with the above-discussed instruments, the national government still plays a key role in supporting municipalities in social housing development and has shown a considerable degree of policy stability.”

- “While continued national influence is relevant in both cases, it is also the lack of influence of a scalar level – particularly the supra-national level – that requires consideration. The Netherlands as well as Sweden, two countries with comprehensive social housing supplies, have restructured their sectors following measures at the EU level in response to complaints by private landlords about unfair competition through housing subsidies in the early 2000s. The Netherlands introduced stricter income limits and targeted the social housing sector more closely to lower-income households. In Sweden, the parliament ruled that Municipal Housing Companies needed to operate in more business-like ways, aiming to create a more level playing field with commercial housing providers (Czischke, 2014; Elsinga & Lind, 2013). In Vienna, this issue has so far played no role. The Austrian system of social housing has at least so far proven resilient in legal terms (Streimelweger, 2014). This also holds for Finland and Helsinki.”

Shane Phillips 0:04

Hello, this is the UCLA Housing Voice Podcast, and I'm your host, Shane Phillips. This episode we're talking to Professor Justin Kadi about the success and stability of social housing in Vienna and Helsinki, and comparing their positive record against the decline of social housing programs in many other cities and countries where they once played a much larger role in the housing market. A good chunk of this conversation is about what sets Vienna and Helsinki programs apart, and what we can learn from their unique approaches. But building on our episode about France's social housing program last year, we also wanted to spend a lot of our time talking about social housing more generally, and getting a better understanding of all the different forms it can take, and how its planned, financed, built and operated. That obviously has really important implications for places like California that are looking at planning their own social housing programs. I think most of us in North America have a fairly narrow and shallow understanding of how social housing really works in other parts of the world. I certainly include myself in that assessment, and Justin ended up being the perfect person to talk about it with. He's based in Vienna, and that's his expertise so that's where we focus most of our time. But even without much discussion of Helsinki, this episode is rich with information and insights about how world class social housing programs operate, and that is reflected by the exceptional length of this episode but I really think it gives us in the US and elsewhere a whole lot to chew on. The Housing Voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies with production support from Claudio Bustamante, and Jason Sutedja. As always, feedback and show ideas go to me at ShanePhillips@ucla.edu. Now let's get to our conversation with Professor Justin Kadi.

Justin Kadi is an Assistant Professor at the Vienna University of Technology, and he's here to talk about his research on social housing in Vienna, Austria, and Helsinki, Finland, and the comparative success and stability of these two cities' social housing programs compared to others around the world. Justin, welcome to the Housing Voice Podcast!

Justin Kadi 2:16

Hello, thank you!

Shane Phillips 2:17

And my co-host is Pavo Monkkonen. Hey Paavo!

Paavo Monkkonen 2:20

Hey, Shane, how are you doing? Justin, I'm so glad you're here to talk about this paper and Vienna's social housing policy. There's a lot of interest in California about Vienna in particular. I also wanted to thank you for your work as Associate Editor of the International Journal for Housing Policy, because it's a cool journal and I'm sure it's a lot of work.

Justin Kadi 2:40

It is but it's worth it. Thank you!

Shane Phillips 2:42

So as always, we start by asking for a quick tour of our guests' hometown or where they're living and I think, Justin, you're going to give us a tour of Vienna. This is especially appropriate because Paavo was going to be in Europe next year and might be visiting and actually going on this tour. Where do you want to show him?

Justin Kadi 3:00

Well yeah, welcome to Vienna! I think one of the places that everyone interested in housing in particular should visit here is a very famous social housing estate, which is called Karl Marx Hof. It's interesting for the fact that it's one of the or even the largest residential building in Europe. It's over one kilometer long, and has many social housing units in there, and it was built in the 1920s. It exists still and is one important part of the social housing stock in the city. I will also take you to one of the largest green space in the city, which is called 'Cata'. I'm not sure how to translate this to English, it's just a German term. It's next to a large amusement park quiet in the city center, and has one of the largest inner city green spaces, and was actually built or open to the public in the late 19th century. And I will also take you to a place called Danube Island, which is another very important site in Vienna. It's an artificially built Island along the Danube which was built in the 1970s and is a large recreational area in the city and also representative of a very socially oriented urban planning approach that has been for long quite important in Vienna.

Shane Phillips 4:39

No cars there either if I'm remembering right.

Justin Kadi 4:42

Yeah, there are no cars there. And there are also no buildings there. So it's just recreational space.

Shane Phillips 4:49

It's I was in I was in Vienna four or five years ago, and I visited all of these things. Actually, they're some of my favorites.

Paavo Monkkonen 4:56

You didn't go to the Hundertwasser?

Shane Phillips 4:58

i haven't even heard of it, I'm sorry to say. I definitely saw Karl Marx Hoff but I think just kind of riding by on the train. My comment on that as I think Michael Eisen, who has done a lot of work on single-stair buildings, specifically mentions in a report he did for the City of Vancouver, how that building despite its kilometer-long length is actually a bunch of like sequential point access block single-stair buildings. It's not this, you know, long corridor building we think of for a long building built in the US. Yeah, the Danube Island was amazing; no cars just and biking all along, it was great. And that the Protter park or whatever was called, I remember walking through the amusement park and just the very long stretch of people biking, walking, riding horses down the road, and no cars there. This was exactly the tour I needed, I guess.

Justin Kadi 5:52

Can I have one more site? So more for the housing nerds among you, there is a street or like an area in the city, which is originally called the 'Ring Road of the Proletariat' which was also part of the social housing program in the 1920s, where the Socialist Party was kind of trying to build an alternative kind of ring road or "Ringstraße" as it's called in German, so not one for the bourgeoisie but one for the proletariat. This is one area where there is a lot of social housing close to the inner city and so that would actually also be a site where I will take you.

Paavo Monkkonen 6:31

So is it tram-based ring road, and not a car based ring road I assume?

Justin Kadi 6:36

So it was a car based ring road. Yeah yeah

Paavo Monkkonen 6:40

So the proletariat had cars in the 1920s?

All 6:43

*light laughter sound

Shane Phillips 6:46

It's aspirational. So the topic of our conversation today is your article with Johanna Lilius, published late last year in Housing Studies. The title of this is "Remarkable Stability of Social Housing in Vienna and Helsinki: A Multidimensional Analysis". The title of our podcasts will likely reflect this, but we're going to focus more on Vienna for this conversation because that's Justin's expertise. We'll definitely discuss some of the attributes of both Vienna and Helsinki social housing programs that set them apart and may help explain why they've been so successful compared to many other cities in other countries, and maybe we'll be able to have Johanna on in a future episode to talk more about Helsinki. So Justin, I want to begin by defining one part of your articles title, the "social housing" aspect, and contextualizing the other, which is the "remarkable stability". We'll start with the definition of social housing which I think is especially important for our US, and maybe just North American listeners generally because social housing is so much less common here than in many other rich countries. In your paper, you say there's no single generally accepted definition of social housing, and it isn't even a formal like legal category of housing. In some countries, it's often used as more of a shorthand. But for the purposes of your article, and for this discussion, when you talk about social housing, what is that shorthand referring to? Or what images should it conjure in our minds? I guess another way of putting this is what criteria do you use to classify homes as social housing or not social housing?

Justin Kadi 8:22

Yes, thank you for this. So for us as housing researchers, this is certainly a challenge, right? It's such a contextually specific term, right? It means that different things in different countries and different cities, sometimes even the end. In our paper, there was another challenge because we wanted to do a comparative piece; comparing two cities in two different countries, and we soon realized that there is no single definition that kind of fits both. I mean there are people that say, "well, social housing means so such different things in different contexts so there's actually no way to compare this". I think this is kind of an extreme position to take because if you follow this argument further then most comparative housing research could not be done. So we kind of adopted a more middle-ground approach you could say. What we can say is we can have, let's say, a more abstract definition of social housing that fits different countries or different cities but we also need in addition to that is more context-specific elements that are specific to the particular cities. And what we did is we kind of take one really common abstract definition in the literature which basically says that social housing means rental housing that is operated on the basis of meeting housing needs, and not primarily for maximizing profit for the landlord. That's ofcourse is very general, right? But it kind of helped us to, on general level, grasp what social housing means in Finland and Austria, and we added more details than to these when we looked at the two cases. And then we can already see that in the Vienna case, for example, social housing means also housing that is provided by particular provider types either by the city or by nonprofits, or as they're called limited profit housing associations - we will talk more about this later still. In the Finnish case, it's not about a particular provider type that kind of defines social housing, but it's more about particular subsidy program. In the Finnish context, social housing means that there is a particular subsidy scheme that is used by the landlords and once the use that, it can be defined as social housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 11:07

Yeah, I was curious about the definition, you chose this idea of operating on the basis of meeting need, and not primarily to make a profit because I think, you know, housing is an investment and a consumption good. Sometimes, these two things get blurred, and that's an issue but on the other hand, housing operated to make a profit also meets a housing need so I wonder whether you're worried about this distinction or not.

Justin Kadi 11:36

Yeah, I think that's a good question. I mean, yes, it worried us to some extent but then, on the other hand, what we were actually looking for on a more abstract level was a more general definition that fitted both our cases. That's what the definition that we that we chose there did, but I think you're absolutely right. I mean, these two functions of housing, often overlap, right?

Shane Phillips 12:08

I think one way to, we might come back to this, but I think one way to think about it as well might be that social housing is housing that is priced at a level that it could not have been built without some kind of public support, if that makes sense.

Paavo Monkkonen 12:26

Although, I mean, I guess so for me, the issue is like, thinking about the intention of someone's action to me is less important than the outcome of the action. So like in the US 50 years ago, there was a lot of housing being built nd housing was relatively affordable. All the people building the housing perhaps were a bunch of jerks, but like, who cares, right? This idea that, you know, if the goal is pure then the outcomes will be pure. I don't know. I mean I think for the policy discourse, there's this idea that we'll get into, which is that if we just didn't have developer profits, housing would be affordable. And so that's something that is very curious to both of us. I think about the case of Vienna because I don't think in California, if you remove developer profits, I don't think the new housing would be extremely affordable, right? Yeah.

Justin Kadi 13:17

Yeah. Very good point.

Shane Phillips 13:18

I mean, to your, we're just going to keep going on a digression here, but I mean I think this is interesting, and we'll see how much stays here. There's, to your point about, Paavo, or counter to your point, housing that was built in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, if it had been social housing, you know, it wouldn't be renting for so much today in California, or in Los Angeles because they would have had rules set to it where when the circumstances changed, the owners couldn't just charge as much as they liked. So there's still some difference there even if when it's built, it's not necessarily all that different.

Paavo Monkkonen 13:56

Okay well, I have another counterargument!

Shane Phillips 14:00

We'll get there! So I do want to make sure we talk about this in a US context as well. I said that social housing, I think, is relatively rare here in the US but we do have some kinds of housing that we might categorize as either non-market based or subsidized or perhaps social housing. We have about 2 million homes that exist right now that were funded by the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, and they have to be rented at below market rates to low-income households for at least the first 30 years of operation usually. We have another million or so public housing units that were mostly built decades ago, and those are reserved for very poor households and owned by the government mostly. Justin, just so I understand how you're thinking about this - those are probably social housing by your definition, right?

Justin Kadi 14:48

Well, I mean, if you just pick this general definition that we pick to kind of fit both our cases in there, I would say those can be considered social housing, but I mean if you take a more restrictive definition... there are people, and I think that they have a point, they say social housing is not just about housing that is kind of operated on a basis of need and not just profit, but they also say it needs a specific provider type. So it needs, for example, either nonprofits or it needs municipalities or cities or some kind of state actor, and in that sense, I think there's a question whether housing funded for low-income housing tax credit, and is basically provided by private landlords, can be counted as social housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 15:42

Yeah, it's a good point, or building them in most cases.

Justin Kadi 15:46

Exactly! I mean, I think that there's an interesting parallel here to the German case, right? Social housing in Germany for the most part has been provided by private landlords that were subsidized. Then a bit similar to the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, housing that was subsidized through these programs was part of the social housing stock for a limited period of time. After the subsidies ran out, they returned back to the private markets. So I think there's some debate also within the Housing Studies community whether this can be counted as social housing or not but I think it's an interesting parallel to the US case.

Shane Phillips 16:23

Yeah. So last year, we did a great interview on social housing with Magda Maoui but that one was focused on France. And something we didn't really do in that conversation all that much was get into the details of how social housing is financed, built, and operated, and I do want to make sure that we do a bunch of that here especially since we've got a few different programs that we can compare and contrast. Putting my cards on the table here, one reason I want to do this is because in the US and Canada, I feel like there are a lot of misconceptions about social housing and a real lack of imagination about the different forms that it can take. It sometimes feels like people here just imagine social housing is like US public or nonprofit housing, but just better funded. And I don't think that's a very accurate or useful depiction. You happen to have a great table in your paper comparing some of the key features of the social housing programs in Vienna and Helsinki, and I'd love to walk through at least, the Vienna column of the table and explore how social housing in Vienna works in its different forms. So there's like six different dimensions here, you've got: definitional characteristics, the providers, whether a down payment is required to enter, whether the social housing units remain in the social housing stock permanently or for a limited time only, how much cheaper social housing is than private renting, and whether there are upper income limits, or to what extent there are upper income limits for tenants to participate in social housing. I guess we can start with providers. In Vienna, tell us a little bit more about the providers of social housing and maybe we can combine this with talking about the difference between Council Housing and Limited Profit Housing Association Housing

Justin Kadi 18:09

Yes, thank you! One of the important points to know here is that in Vienna, there are these two providers that you just mentioned. It's either the city that provides as we call council housing, or it is limited profit housing associations that provide limited profit housing association housing. In terms of size, they are about the same size and both of them account for approximately half of the social housing stock.

Shane Phillips 18:39

And the social housing stock is about 40% of the overall housing stock in Vienna, correct?

Justin Kadi 18:44

Exactly, yeah.

Shane Phillips 18:45

So each accounts are about 20% of the overall stock.

Justin Kadi 18:48

Exactly, yeah! So the city is pretty straightforward to understand, so that the municipality in this case that works or acts as a provider. 'Limited profit housing association' is perhaps not such a familiar term or concept, and I think it's pretty unique to the Austrian context. It's something similar to nonprofit housing, but then it's also again, really context specific. So basically, what limited housing profit associations are in Austria, these are private providers that operate on the basis of meeting housing needs. So their primary goal is to provide affordable housing for the residents, and the kind of the 'limited profit' part of their name already tells that they are allowed to make some profit but only very limited profit. They have become the most important in terms of nationwide in Austria, and they have also become the most important provider of social housing.

Shane Phillips 19:58

And something I wasn't clear on from the paper was whether like every project has its own limited profit housing association or whether it's, you know, a smaller number of them that are responsible for building lots of different housing over time. Which is the situation there?

Justin Kadi 20:14

Yeah. So it's the second.

Shane Phillips 20:19

Because I can imagine them being confused with like cooperatives where you just get together a bunch of prospective homeowners who build a project, and they all own it. But they just own that that building, and it's just their association for that one building. This is a very different model.

Justin Kadi 20:36

Yeah, I mean, what is important to know is that there is a variety in sizes, between the different limited property housing associations. So there are some that are quite big, and there are also others that are smaller. I mean the biggest ones are like really big players in the market so like the biggest has like 150,000 housing units in Austria. So it's really a huge player but there's also others that have like one or two buildings, right? So you cannot generalize about it but I think the easiest way to understand this is also to contextualize and understand how they emerged historically. Historically, they did emerge out of the idea of cooperative housing - people coming together and saying, "we want to establish an alternative to private market housing", and that was something that started around the beginning of the 20th century. It was really kind of a bottom-up movement, and over the course of the 20th-century, it kind of got incorporated more and more into, you could say, legalized and institutionalized forms of provision. It was kind of formalized also, through laws and became one very important part of how social housing system in Austria works.

Shane Phillips 22:05

I'm trying to place limited-profit housing associations in a US context. I think it seems like it might be fair to just compare them to our nonprofit builders because they have developer fees, and they they're not losing money. It's just they're not, you know, expecting certain percentage return on investment and they just have a flat fee. And maybe it's a little different in Vienna, where there's a flat percentage, kind of like how a lot of utilities operate, where they can make a 5% profit, but no more. But they can always make that 5%, whatever they spend. So maybe just, we can just think of them as nonprofits here but kind of in some cases, on a much larger scale, and a little more institutionalized in Vienna or in Austria. I did want to bring up here, could you tell us a little bit about the downpayment requirement for the Limited Profit Housing Association housing in Vienna? Because that seems like a an important barrier, and I'm curious how much of a barrier it really is to households. On the one hand, you point out that limited profit housing rents for about 30% less than housing on the on the private rental market, but you also have to pay some kind of upfront cost. And I wonder, you know, how many people can't access this housing type because of that.

Justin Kadi 23:23

Yeah, so downpayments are an important part of understanding liberal profit housing in Vienna. The easiest way to kind of grasp what this is about is by looking at the financing of new projects in limited profit housing. So if a new limited profit housing project is built then there are usually four pillars of financing. The first is a subsidy that the housing association gets from the city. The second part is a loan that it takes out from a private bank. This third one is equity that it takes from their own revenues, and the last part is the tenant downpayment. The tenant downpayment's idea is that it accounts for a share of the major costs of production, which is land, construction and financing costs. So in the past, these down payments were rather low, and we're not really a large barrier. They were there but they were not a huge barrier financially. They increased particularly beginning in the late 1990s, and early 2000s, and then also in the decade afterwards especially driven by land costs because the cost of land got so much more expensive. We were at a situation, in around 2009 where there is an interesting study that came out that looked at the average downpayment that people have to pay who want to enter limited profit housing in the city. So this study found that on average, potential residents have to pay 500 euros per square meter in down payments upfront before they can enter the unit. So if you say, as a family, you want to rent an apartment of let's say, 100 square meters, then you would need 50,000 euros basically upfront to pay the term. Yeah, that's quite some money. I mean, there are subsidy programs by the city that help tenants so there are low cost loans that people could take out from the city. Still, this was this was quite a significant financial barrier, and is one explanation why if you look at the social housing stock in Vienna and compare, let's say, the average income in city owned council housing and limited profit owned housing then traditionally the limited profit housing is much more oriented towards the middle class and people with more financial resources. I think the downpayment explains a part of that.

Shane Phillips 26:24

Yeah, and I think we'll probably come more to council housing a little bit and some of its history because it relates very much to this, you know, discussion of the stability of social housing in Vienna. I did just want to note for the listeners that council housing is cheaper than limited profit housing in Vienna. As I mentioned, limited private housing is about 30% cheaper than private rented dwellings. Council housing is about 60% cheaper so it is very, very inexpensive, and this is the stuff that is city owned. We'll also come to the income limits - we have a separate question about that so I'll save that for later. I did want to quickly just ask about the permanence of social housing in Vienna specifically, can you tell us a little bit about that? It seems like with the exception of a kind of federal government-led sale a decade or two ago, social housing in Vienna is pretty hard to convert to private ownership.

Justin Kadi 27:17

Yes, that's true. So the city-owned constant housing stock has remained almost untouched. There have been very few units that have been sold but those account for some 100 units compared to a stock that includes like 220,000 units. So basically, all the weights that were part yeah, very niche negligible. Exactly. In the limited profit housing stock, some units have been sold particularly through a right-to-buy program. So where sitting tenants were offered the unit, and they could kind of buy it and then become homeowners. And also some limited profit housing associations were sold particularly those owned by the federal government in the early 2000s. But then what I think is important, and probably what you're still trying to get at is that the intention of both council housing and limited profit housing in Austria, and also in Vienna is that once you built this housing, the general idea is that it stays in the social housing stock permanently or forever which I think is an interesting difference also, in terms of how social housing works in Vienna compared to other places also in Europe. Because there are places, for example like Germany, where social housing is often working in a way that the private landlords get subsidies and then after like 30-45 years, the subsidy period ends, and then it returns to the private market similar to the Low Income Housing Tax Credit.

Shane Phillips 29:04

Exactly, yeah! This is how the Low Income Housing Tax Credit Program works, and the time limit varies state to state - it's 30 years in most places, and it's 55 years in California, and a few others. Okay, we can move on from there, and I think there's another contrast to the US that might be interesting here, and this is on subsidies. So you know that 80% of new construction in Austria between 1992 and 2002 received some kind of subsidies, and that had declined to 49% of new construction from 2007 to 2017. I imagined that is at least partly explained by the stop that was put to new council housing construction; that prohibition or stop, that had been in place for most of the 2000s and the 2010s and as your article talks about, has recently come back. What I'm really curious about is what form those subsidies take. Here in the US, projects that receive subsidies tend to be deeply affordable and entirely reserved for low income households. Each unit requires very deep, and large subsidies on the order of several hundred thousand dollars. Certainly in California, given our construction costs so someone might hear that half of Austria's new homes are subsidized and think they're all being paid for almost entirely with public funds with very little contribution from private sources. Maybe that is the case but it's my impression that Austria subsidies tend to be wide but relatively shallow, where they help a lot of projects, but they're not necessarily accounting for most of their funding at the project or at the unit level. Whereas in the US, our supply side subsidies like that low income housing tax credit, tend to be deep but very narrowly focused on a small share of the new construction market. Does that sound right to you? And what else can you tell us about the different forms that housing subsidies take in Vienna, especially on the tenant side, and on that supply side for funding new construction?

Justin Kadi 31:04

Yeah, so I think what is important if you look at subsidies and types of subsidies that went to housing and how they developed over the last say 20-30 years then you'll see one important shift internationally; you'll see that in the post-war period (1960s - 1970s) days, most of the subsidies in many countries were granted as so-called 'object-side subsidies' so they were basically subsidies granted by public authorities so that the production of housing is becoming cheaper, What do you see since then..

Shane Phillips 31:41

.. and we would call those supply-side subsidies in the US, just for our listeners.

Justin Kadi 31:47

.. and what you see in the 1980s and 1990s in many contexts, and I think (correct me if I'm wrong), the United States is a good example for that is that increasingly, there is a shift from the supply side subsidies towards subjects like subsidies, or as you could also call them housing benefits, which basically, were the idea then shifted. It is no longer that the production of housing is subsidized so that it becomes cheaper, but the tenants or the residents are subsidized so that they can afford housing; usually housing that is provided by the private market. If you look at the Austrian and the Vienna context, I think it's quite interesting that this is quite an outlier here. Because if you look, for example at the European Union, I think we have the statistic in the paper: the share of subsidies that goes to supply subsidies in the European Union is somewhere around 26% of all subsidies that go to housing at the moment. In Austria, it's somewhere around 69% and so it's much higher compared to many European countries at least. The focus on supporting the production of inexpensive housing, and not supporting tenants in affording market- rate housing is a much more common story here. That is also the case in Vienna. Most of the subsidies are granted for, as you say, supply-side subsidies. There is a very small share that goes into supporting tenants, and there's also a share of subsidies if you kind of look at the overall subsidy budget that goes into renovation, right? That's another important part, and providers can also take on subsidies for that. What is also important to know about the subsidy system, though, and I think you kind of indicated that in your question already, the usual financing for social housing project in Vienna draws on different sources of finance. The subsidies from the state make up one important part, but it usually does not account for more than say a third of the overall financing costs. And even more, most of the subsidies are actually provided as low cost loans. They are not provided as lump sums that basically are transferred from the state to the provider, but are provided in a way that the housing provider gets this money as a loan and over time pays it back to the state including interest. For the state, it's kind of a business case, right? They even make money with this. Especially limited profit housing, there is an important role also for private banks that also provide loans to the to the associations. I think we talked a bit about this before but there are also tenants that pay a certain contribution. There are different sources of finance and I think actually, as we also hinted that in our paper, we also believe that is an important part of explaining the stability of social housing sector in cases like Vienna because politically, given if you have so many different sources of finance, it becomes much more complicated for one stakeholder like the city or the federal government to say, well, "let's just get rid of social housing" because the social housing providers have so many different sources of finance that they could then just use instead. I think that also in that sense, it's interesting to think about how the financing works there.

Paavo Monkkonen 35:47

The case for complexity! One question - so there's the subsidized loans, is there an unlimited supply of subsidized loans or are these limited profit associations competing to get these subsidized loans?

Justin Kadi 36:01

Yeah, they're competing, and I think that's also a very important part of how the subsidy system works that we do not highlight sufficiently in the paper, I think. Thanks for bringing this up. Because in Vienna, there's an instrument, which is called "housing provider competition", if you translate it literally. So basically, whenever the city gives subsidies for a project, providers have to hand in their proposal around what they want to build. So basically, this includes predefined pillars - what kind of criteria every project has to fulfill. It also includes architectural quality, it includes affordability, and it includes ecological dimensions. Whoever puts forth the best project, gets the subsidies. And that is, I think, a very interesting instrument because what it actually does is that it makes the providers compete over quality and I think, a very interesting instrument to also understand why so much of the social housing that is constructed in Vienna is of such high quality.

Shane Phillips 37:21

I think this is really important, too, because just as a distinction. If I'm hearing you correctly Justin, and based on my recollection of how Vienna builds a lot of its housing, what you're saying is that Vienna the city may have acquired a site and may have already owned a site, but then it sort of puts out a competition for that location. And people can submit a proposal, you know, meeting all of these different dimensions and trying to out compete other people. Is that how it works in Vienna, because here in the US, it's very different? You basically have individual builders - let's just limit ourselves to the Low Income Housing Tax Credit builders for now; they have to go there, find their own site, come up with their own plan, and then they just submit their proposal for their location. No one else can even submit anything, because they're the only ones who own it. So there's no competition in that sense. There's only competition once you've submitted your proposal for people who have other sites that they also want to build. And maybe, you know, you have to out compete them for the grants or the tax credits. Is the way I described it for Vienna, though, where it's the city owned or government owned site that is then sort of baited out almost or put up for competition. Is that how it works in Vienna?

Justin Kadi 38:36

Yes, that's how it works usually. And often, part of the subsidy that the city then provides is also that it sells the land at a lower price to the provider than it will be sold on the private market. And that's particularly important for limited-profit housing associations because land prices here have also become a problem for the provision of social housing units. They have become a problem, particularly because there's a legally defined limit to how much land can cost so that limit profit housing associations can still use subsidies to build new units there. I think it's actually it's quite a smart rule, because what you want to do is to make sure that the land owners don't speculate with land and sell it to limited housing profit associations at a very high price then the government or the city has to pay a very high subsidy so that the housing built there is affordable. So to avoid that, they say, "well, you cannot buy land for more than 200 euros per square meter but then given that land prices have increased so much that the available land at that price has become very scarce, so in that sense, the city is increasingly using the land that they own, and then kind of try to sell this to providers at lower price. And so with that, kind of circumvent this legally set maximum limit of net presses.

Shane Phillips 40:21

And I think one more clarification here, is this mostly land that Vienna already owns? Or is it also going out and acquiring land? Because I think, you know, in the US context, our cities tend not to own very much land. I know, in your paper, you wrote how Helsinki owns 64% of the land in the city, and so they got a lot of land to work with, to kind of give away when they want to, and that's not so much of an option here in the US in most places.

Justin Kadi 40:49

But I think there's two things to say about this in Vienna. The first thing is that we don't know so much, right? It's really not very transparent, right? So the city is very secretive about this, and probably for good reasons. But the other thing is that what we do know is that the Vienna does not own as much as Helsinki, but we also know that they are trying to acquire more. But there's also, I think, a fair amount of critique that the city is giving away, and selling a lot of land that they own, and not using other ways of making sure that this land is used. Especially the kind of critique here is that the city could also continue ownership, and then lease it to providers and not sell it or give it to them. So I think that's that in terms of kind of keeping control of that land over time also.

Shane Phillips 41:47

Yeah, so they don't end up having to buy it again in 100 years or something. Okay. So I said at the very beginning, that we were going to define social housing, and then talk about its remarkable stability, I think we've done a pretty good job of defining more than halfway through our interview here. So let's go all the way back and contextualize this, what you call remarkable stability of social housing in Vienna, and Helsinki. As you mentioned, a rather large stock of social housing has stuck around for several generations now in both cities. This is remarkable because it's not the experience of many cities. Plenty of cities, and countries built lots of social housing in the post World War II era but since around the 1980s, the stock has been in decline in most of those places. So just as a general overview, in what ways has social housing been eroded or degraded in other cities and countries? And how big are the losses that we're talking about here?

Justin Kadi 42:48

Yes, I think what we wanted to highlight with the paper is that these cities are really outliers. If you look at international experience, particularly in the European context, where social housing used to be much bigger in most countries and cities in let's say, the 1970s, or 1980s, and I think there are some iconic cases that are often discussed. The United Kingdom is certainly one of them if you, for example, look at the kind of the high time of council housing in the United Kingdom, there was a time when it accounted for almost one third of all housing units in the country. By now it's less than 20%, and in pretty steep decline following pretty aggressive measures of privatization starting in the 1980s, and the very intensive promotion of other tenures particularly home ownership since then.

Shane Phillips 43:50

I mean, I think that's an exceptional and really interesting case, we'll have to have an episode on it. My understanding of what happened there was, you know, this was during the Thatcher administration, and it wasn't necessarily even entirely about the housing or about the budget. It was just like "government is bad, and we don't want government owning things so we're going to kind of get rid of this out of our ownership". They gave the residents of these council housing units, the opportunity to buy the homes at I think it was well under half of what their market value would be. And, you know, not surprisingly, a lot of people took advantage of that you'd be kind of foolish not to, but then, you know, they effectively captured all of those the difference between what they paid and the market value. And that affordability is just kind of permanently lost for all of those homes.

Justin Kadi 44:36

Yeah, and I think maybe to add to this, I think it's quite perverse what happened in the United Kingdom because if you look at what happened with these units over time. There's a very interesting recent study that found for example, that 40% of the units that were sold since the 1980s for the "Right to Buy" program are now rented on the private rental market and often these units are not affordable to the tenants so the state, again, pays huge amounts of housing benefits to private landlords that it did not have to pay in the past to keep these houses affordable. In many different ways, I think this is a very important case to study in terms of understanding policy failure, and, and lots of other things. I think the United Kingdom is an iconic and often discussed case, but there's there's other cases in Europe that show similar trajectories. If you look at Germany, for example, Germany also had a social housing stock, which was larger than 20%, at some point, and is now way below 10%. One of the countries with the largest social housing stocks is the Netherlands historically, at some point, the country had more than 40% of their housing in social housing, and now has below 30%. So also there, the decline has been pretty steep since the 1990s. I mean, here we are talking about, you know, national housing stocks, right, and so a 10% change there is really a lot of units because maybe 10% doesn't sound so much, but it's quite something right? Those are the kind of country-level statistics but I think we know also that similar things happen at the city level, and often they were even more pronounced there because often social housing was concentrated in cities. Berlin, for example, I think is a very interesting case. Berlin, at the beginning of the 1990s had more than 30% of their housing in the social housing stock and now it has about 9%. Right? So a huge shift there also. Amsterdam is another case to mention, perhaps, which at some point had more than 60% of their housing in social housing, and now has about 47%. Again, also here quite a huge decline. I think, in that sense, if you look at Vienna and Helsinki, where social housing has basically over the last 30 years remained stable, that was something that we wanted to highlight with the paper because that's just really kind of going against the broader trend that seems to dominate most of the context, at least in in Europe, but also seems to kind of dominate most of the debate around social housing. That's what we kind of wanted to question.

Shane Phillips 47:47

Yeah, and you make an interesting point in the article that on the one hand, every country has a unique origin story for their social housing programs. They were established for a variety of purposes, they were intended to benefit different groups of people and projects were financed and built and managed in different ways. On the other hand, the decline of social housing looked pretty similar. The exact mechanisms vary, but it was pretty similar everywhere it occurred. I'd like to come back to what made Vienna and Helsinki's programs so resilient. But let's first talk about the attributes of the programs where social housing has declined. So Justin, in your paper, you identify four big shifts that led to this general decline in social housing across so many places. Could you tell us about what those are, and if you can just define each and give a quick explanation of them?

Justin Kadi 48:37

Yes, sure. So the first very obvious dimension that we looked at was a declining sector size. So basically a relative decline in social housing compared to other tenures. If you look at kind of real world developments that was particularly homeownership over the last 20-30 years, but also kind of declining sector size also means for us not just a relative decline but also an absolute decline of the stock which can happen due to different reasons, be it privatization that we just talked about but it can also, of course, involve demolition - something that probably rings the bell for some US listeners. The second dimension that we looked at was stock privatization so basically a transfer of units to private owners, that can again happen through different mechanisms. It can either be through selling directly to tenants, through a 'Right to Buy', as we call it, or it can also, for example, be through like in Berlin the so-called on 'block sales' where whole housing estates are sold to investors. It can also be again, this happened in the German context and also in other contexts through the conversion of owners or providers from former public or nonprofit entities into private companies, so basically you don't sell the unit but you convert the owner from a nonprofit to a for-profit owner, and through that also, stock gets lost and privatized. The third dimension for us includes a shift in housing production. So if you think about the decline of social housing, we think that it's important to also see that social housing as a kind of position of social housing in over housing production has shifted in many countries. And right, yeah, and that is related commonly through a shift from supply subsidies to subject subsidies. And I think that's something that you can see in many countries, and so entered the fourth dimension is that, for us, that is the question of residualization so that social housing stock becomes more residual - what that means is that the socio-economic profile of the tenure becomes more dominated by poorer households. Basically, to put it in other terms, the tenure is increasingly catering to lower income households. That can either be an intentional policy, right like it happened in the Dutch context, for example in the Netherlands, but it can also be an unintended side effect of course of other other policy decisions. More remarks about this, what we wanted to do with kind of distinguishing these four dimensions was to have a more complete picture of what social housing plan means. Because if we look at how people understand it, particularly in the academic literature, we see that people use different concepts and refer to different things. Some use it to say, "well, you know, the absolute size of the sector has declined", and others say, "well, you know, stock has been privatized, again", and others will say, "well, you know, housing production has shifted". So we thought that what what we have to do is to arrive at a more comprehensive understanding, and we'll have to look at all these dimensions together. That was an intention of having this multidimensional framework.

Shane Phillips 52:13

Yeah, that makes sense and I think it is helpful. The first two concepts declining sector size and stock privatization, I think, are fairly straightforward. I did feel like the other two were a little more nuanced and worth exploring further. Shifting housing production was the third change, and we've kind of already talked about this in the context of supply-side versus demand-side subsidies so I don't think we need to get into a ton of detail here. I will note that we have a conversation about sort of the balance between supply-side and demand-side policies or subsidies or interventions with Diego Hill in our episode about Chile's housing policies and the neoliberal turn that they took, and I just kind of want to reiterate the need for a balance between those two things. Maybe how a lot of places have shifted too far in the direction of demand side policies like housing vouchers, and that kind of thing. I really think we should like pay a lot of attention to the fact that Vienna has such a higher share of its housing subsidies going toward, you know, object side supply side toward actually building housing, and housing that the market just would not build by itself because it couldn't earn a profit at the rents that are being charged. The fourth trend, though, is when I think we talk less about this is residualization. And that's the shift in policy away from programs with maybe broad eligibility requirements and toward those that are much narrower, and usually only for lower income households. In the US, we certainly see this in the means testing of you know just about everything. In our rental housing sector, virtually all resources are targeted at households earning around 60% of area median income or less. I think at some level, this sounds very sensible, like why wouldn't you try to allocate limited public resources to the people with the greatest need, but there are serious downsides to this approach as well. I was hoping you could talk about what residualization has looked like in the context of social housing in these different countries, and how residualization has undermined or you think it has undermined both the function of and the political support for social housing. And maybe we can ask Paavo to kind of tie this to some of our experience here in the US with public housing and other things too.

Justin Kadi 54:33