Episode 33: Housing Transfer Taxes with Tuukka Saarimaa

Episode Summary: In recent years, many cities have turned to real estate transfer taxes to capture a share of price appreciation and generate revenues for public purposes. Transfer taxes are relatively popular with voters, and they are easy to collect, but they also have disadvantages compared to property taxes and land value taxes. (Shane has also endorsed higher, more progressive transfer taxes in Los Angeles.) Professor Tuukka Saarimaa joins us to discuss one such drawback from his research in Helsinki, Finland: by increasing the cost of moving, transfer taxes may reduce household mobility, making it less likely that people will live in the housing best suited to their needs. But while imposing taxes can discourage socially beneficial activities, spending them can also improve people’s lives, and we consider how this balance is met with housing transfer taxes in particular.

- Eerola, E., Harjunen, O., Lyytikäinen, T., & Saarimaa, T. (2021). Revisiting the effects of housing transfer taxes. Journal of Urban Economics, 124, 103367.

- Phillips, S. (2020). A Call For Real Estate Transfer Tax Reform. UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

- Martin-Straw, J. (2022 May 20). City Budget Sessions – Property Transfer Tax Debuts as 3rd Largest Income Source. Culver City Crossroads.

- Wagner, D. (2021 Dec 17). Ballot Initiative Aims To Fight LA Homelessness By Taxing Top-Dollar Property Deals. LAist.

- Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2013). Does high home-ownership impair the labor market? (No. w19079). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Freemark, Y. (2020). Upzoning Chicago: Impacts of a zoning reform on property values and housing construction. Urban Affairs Review, 56(3), 758-789.

- Saarimaa, T., & Tukiainen, J. (2014). I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member: empirical analysis of municipal mergers. Political Science Research and Methods, 2(1), 97-117.

- Bratu, C., Harjunen, O., & Saarimaa, T. (2021). City-wide effects of new housing supply: Evidence from moving chains. VATT Institute for Economic Research Working Papers, 146.

- “Housing transfer taxes are typically seen as an inefficient form of taxation, but are nonetheless fiscally important in many countries (e.g. Mirrlees et al. 2011 and Andrews et al. 2011). Transfer taxes drive a wedge between the cost of buying a house and the price received by the seller and thereby reduce the likelihood of a mutually beneficial transaction. Because of the tax distortion, in some cases, no transaction occurs even though the prospective buyer values the house more highly than the current owner. In countries where most households own their home, such as the UK and the US, transfer taxes may also affect household mobility as moving requires the sale and purchase of houses. Through their effects on mobility, transfer taxes may influence not only the allocation of housing units to households, but also the allocation of jobs to employees.”

- “In Finland, the housing transfer tax applies to all housing transactions, both new construction and resales. The buyer is responsible for paying the tax and officially becomes the owner of the housing unit only after the transfer tax payment has been received by the tax authorities. First-time buyers under the age of 40 are exempt from paying the tax. As in many other countries, not all transactions face the same tax rate. In the Finnish system, the tax rate depends on the type of housing unit. Currently, the tax rate for housing units in housing co-operatives is 2% and 4% for properties, meaning single-family houses.”

- “We study the effects of the housing transfer tax on household mobility in Finland, a country with a high homeownership rate, using high-quality register data on the total population from 2005 to 2016 … We exploit a tax reform that increased the transfer tax burden on apartments, while the tax treatment of houses remained unchanged. Until the end of February 2013, the transfer tax rate was 4% for houses and 1.6% for apartments. In both cases, the tax base was the transaction price. On March 1, 2013, the transfer tax rate for apartments was raised from 1.6% to 2% and the tax base was broadened to include housing co-operative loans linked to the apartment.”

- “However, in a housing market setting this type of design may be flawed due to spillovers between the treatment and control groups. If homeowners in the treatment group move less often because of the tax increase, homeowners in the control group may also be indirectly affected as they have less trading partners to interact with. As a result, the DID estimate would be biased towards zero as it is a combination of the true treatment effect and a spillover effect. The key contribution of this paper is to quantify the bias caused by the spillover effect. We are able to do so because we observe in our data not only if a household moves, but also to which housing type it moves. This allows us to calculate the mobility rates between and within the treatment and control groups.”

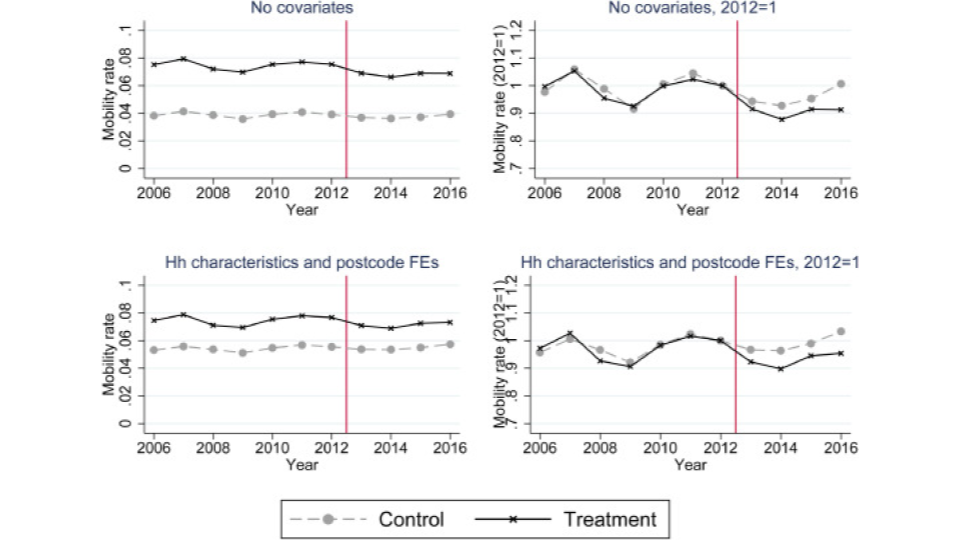

- “Three observations stand out from Fig. 1. First, the mobility rate is clearly higher in the treatment group than in the control group throughout the time period (upper left panel). This is true even after controlling for household characteristics and adding postcode fixed effects (lower left panel). Second, the trends in mobility rates are similar in the treatment and control groups in the pre-treatment period … Finally, after the tax increase, the mobility rate decreases in both groups, but clearly more so in the treatment group. The divergence also persists for four years after the reform.”

- Figure 1.

- “Our main finding is that the transfer tax has a significant negative impact on mobility. Combining quasi-experimental analysis with a model-based analysis, we find a roughly 7.2% reduction in treatment group mobility due to a 0.5 percentage point increase in the transfer tax rate. Our DID estimate for the effect is roughly 5.6%, suggesting a 22% downward bias in the estimate. The bias arises because mobility also decreases by 1.6% in the control group … When the tax rate on apartments is increased from 1.5% to 2.0%, the mobility rate of those living in houses is reduced from 3.90% to 3.84% or by some 1.6%. At the same time, the mobility rate of those living in apartments is reduced from 7.40% to 6.86% or by some 7.2%.”

- “First, we analyze outcomes related to the labor markets. We find that the transfer tax affects short-distance moves (less than 50 km) more strongly, but we also find negative effects on long-distance moves (more than 50 km), suggesting that the transfer tax also affects the labor market. This result is in contrast with the only previous paper studying mobility instead of transactions – Hilber and Lyytikäinen (2017) – which finds that the transfer tax only affects short-distance moves (10 km or less) in the UK.”

- “Second, we analyze more closely the different margins of housing consumption adjustments highlighted in the literature on housing consumption over the life-cycle. As one would expect, the tax increase affected moves involving small adjustments in housing unit size most strongly. However, these effects are asymmetric so that upsizing became less frequent, but there were no effects on downsizing. This asymmetry is in line with a life-cycle model where credit-constrained households gradually climb the housing ladder by making small upgrades in unit size with multiple moves and downsize maybe only once towards the end of the life-cycle. Together these results suggest that when transaction costs increase, upsizing takes place through fewer moves over the life-cycle, but downsizing may be unaffected.”

- “Our estimate for the cost of public funds of the reform taking the spillover effect into account is 2.3, while the estimate relying only on the DID estimate would be 1.3. Thus ignoring the spillover effect would lead to a substantial underestimation of the welfare costs of the transfer tax … [For a non-distortionary tax, one tax-euro collected from the private sector is worth exactly one euro for the private sector and the cost of public funds (CPF) is equal to one. The larger the welfare cost related to the tax, the larger the CPF].”

- “As suggested by Mirrlees et al. (2011), transfer taxes may influence labor market matching through decreased household mobility.16 We use two complementary strategies to analyze labor market effects. First, we look at labor market outcomes directly by analyzing whether the reform had an effect on the probability of changing jobs, both with and without conditioning on moving. Second, we differentiate moves according to the distance of the move … Based on the figure, there are no notable effects on job changes, although according to the regression results there is a marginally significant negative effect on job changes conditional on moving. However, the pre-treatment trends are not particularly clean for this outcome. At the same time, the standard errors are quite large for these results and we cannot rule out important effects relative to the size of the treatment.”

Shane Phillips 0:04

Hello, this is the UCLA housing Voice Podcast. I'm Shane Phillips. Before introducing this episode and our guests, I'd like to quickly share that the Lewis Center and Institute of Transportation Studies are holding our first in person UCLA Arrowhead Symposium since 2019, and this year, our focus will be on housing. It's happening at Lake Arrowhead from October 16 to the 18th, there are still some tickets available for purchase, and they include everything registration, lodging and meals for the two-and-a-half-day event. If you live in California and work on housing in some capacity, or if you work in transportation, and see housing policy as something that will influence your work in the coming years, we invite you to attend. I'll be there along with the Housing Voice co-hostss as well as a bunch of very smart housing scholars, policymakers and practitioners. You can learn more about this year's program and register at www. UCLAarrowheadsymposium.org. Our guest this time is Professor Tuukka Saarimaa from Aalto University and Helsinki Graduate School of Economics, both in Finland, and our topic is housing transfer taxes. We will review what transfer taxes are early in this interview. So I'll keep the intro short and just say that this was a great and I think very clear discussion of the benefits and possible drawbacks of using transfer taxes to generate additional government revenue. The detailed nature of Finland's administrative data gives us insights into the impacts of policies that are often hard to duplicate in the US since the data quality just isn't that the same level, so we're able to benefit from what they're learning 5000 miles away. Higher, more progressive transfer taxes have been adopted by quite a few US cities in recent years, and they're on the ballot here in Los Angeles in November so it's a subject with very immediate, concrete relevance to many of our listeners. The Housing Voice Podcast is a production of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, and we receive production support from Claudia Bustamante and Olivia Urena, you can send feedback or show ideas to Shanephillips@ucla.edu, and you can give us a five star rating and a review at Apple podcasts or Spotify. Now, let's get to our conversation with Professor Saarimaa .

Tuukka Saarimaa is Assistant Professor of economics at Aalto University and Helsinki Graduate School of Economics, and he's here today to talk about a subject dear to my heart real estate transfer taxes. Professor Saarimaa, welcome to the housing voice podcast.

Tuukka Saarimaa 2:42

Thanks for having me, great to be here.

Shane Phillips 2:43

And Pablo Monkkonen, also as Finnish descent is here as my co-host today. Welcome Paavo.

Paavo Monkkonen 2:50

*says hello in Finnish*.

Tuukka Saarimaa 2:51

*says hello back in Finnish*.

Paavo Monkkonen 2:56

Yes.

Shane Phillips 2:59

Okay, as always, we start out with a tour from our guest. I know we are just a few months too late for the international Social Housing Conference that was held in June so we missed the chance to check out the city then but tell us about Helsinki a little bit, what are the go-to spots you'd like to take friends and colleagues who visit the city?

Tuukka Saarimaa 3:20

Yeah, so if you're visiting during the summer, which is something I really recommend, don't come here in November, I will take you to the default fortress island of Suomenlinna. So you can have because on a sunny day to go there and you can have a nice walk there or have a picnic or to one of the restaurants in the island or or the local brewery and you can also take a car tour there if you want to. And also the boy boat ride to the island is quite nice so you can see the Helsinki Skyline kind of like which is dominated by the Helsinki cathedral and so on. And I would also recommend other islands you know, you can tear boats taking you to these other islands next to Helsinki as well, and this is really nice. I guess if you're an urban planner, then there are there are these new residential areas that we're not building actually right next to the city center. So there's one that used to be a Harbor that we're now changing into our indoor residential area. We're going to have roughly 30,000 new residents in the area and a lot of offices so mixed use, a lot of social housing, and actually some of the events for the conference that you mentioned took place in that in that place so that might interest urban planners. Yeah, Paavo you've been?

Paavo Monkkonen 4:38

Oh yeah, I love it. Helsinki is the best. I recommend the summer and that boat ride fast and I mean, I think people don't realize what an archipelago-style city it is, but Tuukka I thought we were gonna go to a bar. Everyone has a drinking problem. I was gonna recommend, but I googled it yesterday, I think it's closed, did you ever go to the Soviet-themed bar, the Carsmachi Brothers?

Tuukka Saarimaa 5:03

Yeah, I've been there. And we used to take seminar guests there. So it was closed I think in 2019 but I think it reopened in another location. Now after the pandemic, I'm not sure whether it's open anymore, but the original location is gone anyway.

Paavo Monkkonen 5:19

And I shouldn't spoil the idea of it but it was fascinating when we went, there was no one working, and there's this old man and they're drinking by himself, and then he's like, "Oh, Come Drink With Me", and I'm like, "Okay", but it was all part of the deal.

Shane Phillips 5:34

Okay, so this article is in the Journal of Urban Economics, and it's titled, 'Revisiting the Effects of Housing Transfer Taxes, and yourco-authorss are, I'm gonna let you say their names here...

Tuukka Saarimaa 5:47

So Essi Eerola, Oskari Harjunen. and Teemu Lyytikäinen.

Shane Phillips 5:51

Perfect. Housing transfer taxes, for those who aren't familiar with the term are basically sales taxes on real estate, and the rates in my experience are usually between 1% and 5% of the sale price. Here in the US, they're often called real estate transfer taxes, and as the name suggests, they usually apply to non-residential property sales as well. So just as an example, if my city has a transfer tax rate of 2%, and I sell a home for $1 million, I'll owe $20,000 in real estate transfer taxes. Unlike property taxes, which are usually collected year after year, transfer taxes are only paid when a property is sold or transferred. And since they're based on the sales price, the more you sell for the more you pay. One upside to transfer taxes is that you're much less likely to have situations where someone can't afford to pay their tax bill. With property taxes, someone's property value might go up such that they owe more on their annual bill, but their income might not keep up with that, and they could end up with a lien on their property, and maybe even in a worst case scenario, they lose their home. Because transfer taxes are collected at sale when sellers are usually at their most cash rich, this is less of a problem. As I said, this subject is close to my heart because I actually wrote a report advocating for higher and more progressive transfer taxes in Los Angeles, which we'll put in the show notes, and now a few years later, we may be on the verge of passing an initiative that would do exactly that, raising about $800 billion a year for affordable housing, rent assistance, right to council and other important housing needs. But as I acknowledged in my report, and as the research we're going to discuss here today makes very clear, real estate transfer taxes have their trade offs as well. I advocated for them in Los Angeles because we have very sharp constitutional restrictions on increasing property taxes, or frankly, making them any more equitable. And so transfer taxes were a sort of second best option, at least from my perspective, but now that we're really moving forward with them, and a few other smaller cities in our region already have adopted them and a bunch of other places, including various Bay Area cities, and Washington State raised their transfer taxes prior to 2020, it's a good time to take stock of some of the potential downsides here as well. Ideally, this knowledge can inform future changes that will help us get the most benefits out of transfer taxes that we can with the fewest negative consequences, and inform other cities or states considering similar policies. So with all of that introduction out of the way, let's talk about the research. Tuukka, your primary interest here was how housing transfer taxes affect household mobility. That is whether and to what extent transfer taxes discouraged people from moving because they discouraged people from selling their homes because they're paying more in tax. What do we know about the negative effects of reduced household mobility, and why is there a concern that transfer taxes might have that effect?

Tuukka Saarimaa 8:59

Yeah, so I guess the first thing to point out here is that really the effects of transfer taxes depend on whether the housing market is dominated by owner occupiers or renters. So, if renting is the prevailing tenure mode, then I guess transfer taxes should not have, you know, large effects on mobility, or in other words, they shouldn't affect you know, which household ends up living in which housing unit. Of course, there may be some effects on which landlords have been to on which housing unit but maybe that's not a huge problem. But in a situation where people are predominantly homeowners, like I understand it's the case in the US and in Finland, then transfer taxes may affect household mobility,

Shane Phillips 9:47

But not the case, I should say in Los Angeles, where about two thirds or so of our households are renters. It tends to be the case that where prices are highest, you have higher percentage of renters all around the US and I'm sure all over the world too

Tuukka Saarimaa 10:00

So like in general, you know, homeowners usually have higher or larger moving costs than renters because they have to find a buyer for their old house, they need to pay broker fees, etc, and then the transfer taxes come on top of these other costs that are already there. So what happens here maybe a concrete example here would help. So let's say that there's a seller who is who is willing to sell her house for, say, $200,000, and there's also a buyer who is willing to pay at most $205,000 for that house. So here we have a situation where there are obviously potential gains for trade. So for example, the buyer could offer the seller $203,000 for the house, and the seller would happily accept that offer. However, if we were to impose a transfer tax of 4%, here on the buyer, which is now the Finnish case, the buyer is paying the transfer tax, then the buyer would have to offer at least $208,000 for the house in order for the seller to get the 200,000 that she would want for the house. But the buyer is unwilling to do that in this case so we are going to lose this potential transaction here. So why is this a problem then? Well, first of all, it may create mismatch in the housing market so that households do not live in the housing units that will be most suitable for them in their current situation. But the tax may also create mismatch in the labor market because your place of residence is tightly connected to your job location and job market opportunities, and if a better job requires a move, for example, then transfer taxes may prohibit people from changing jobs and moving to better job opportunities. But of course, this isn't ultimately an empirical question whether these are important effects yet that I'm talking about here.

Shane Phillips 11:57

Yeah, so it seems to me that the European scholars of housing especially have been more concerned with the connection between housing markets and labor markets than those in the US, and there's this famous Oswald paper that talks about high homeownership rates leading to unemployment because people can't move to where jobs are. I wonder, you know, is Helsinki have that kind of a problem or why you think European scholars are kind of more concerned about household mobility it seems than those in the US?

Tuukka Saarimaa 12:23

Yeah, I'm not sure why that's the case. Maybe it's because maybe we think that the European labor market is less efficient, we have probably more unemployment than in the US, traditionally. So maybe that's why we're paying more attention to any kind of like, additional frictions that might affect the labor market.

Shane Phillips 12:42

Right, interesting. So before we discuss the Finnish case, which is the subject of your study here, and the particular advantages of the detailed data you're using, and the innovation in your research design, can you talk through how scholars have typically estimated the mobility impacts of transfer taxes in previous research.

Tuukka Saarimaa 13:02

Sure, so I would say that, you know, typically, we economists, we try to find situations where you where for some reason, you have a treatment group that is affected by a tax reform, and then a control group, some individuals or properties were not affected by the tax reform. And so this is important, because, you know, let's say that there's a transfer tax increase, that applies to everyone, and then you want to know whether that tax increase led to lower mobility of households, but now, it's really difficult to disentangle the effect of the transfer tax from all the other changes in the economy that might take place at the same time as the tax reform. And this is a very common problem in any any policy evaluation work that you you may be doing. So like I said, one way to look around this problem is to find situations where are, for example, a tax reform where the tax changes apply only to some individuals or properties, but not to others. And if I take a good example from a recent paper, using data from Toronto, so what happened there was that a transfer tax was introduced for properties within the borders of the city or the municipality of Toronto, but was not introduced in other municipalities in the Greater Toronto Area. So now, because of this kind of like a natural or what we refer to as quasi experiment, you kind of like have a treatment group and a control group. And we did a before and after the tax introduction, you can kind of like tease out the causal effect of the tax increase, and the idea with this design, which is often referred to as the 'difference in differences' design is that that the control group now here, in a sense, captures all the changes that affect both groups in the same way, and if there's any additional difference or any If any additional differences arise after the tax reform, then we're kind of like quite confidently we can argue that this is because of the tax increase and not some other other case, and we are able to estimate the causal effect in essence.

Paavo Monkkonen 15:15

Can you tell me so there's like an econ Twitter, there's a lot of jokes about a difference in differences, is there anything funny or interesting for the normal person, from that conversation?

Tuukka Saarimaa 15:26

Well, yeah, it seems that every week, there's another paper showing, you know, different problems with differences in differences estimation, but I guess, you know, I would call it progress now. Kind of like, we now know much more about what we're actually estimating and what type of estimators we can use here to tease out the causal effect so I'm kinda kind of like happy. And I'm also really happy that this paper has also come up with a solution to the problem that they're fighting so that's nice.

Paavo Monkkonen 15:53

That's always good, not just pointing out flaws.

Tuukka Saarimaa 15:55

Yeah.

Shane Phillips 15:56

Okay, so let's turn to your case study, there was a change to the housing transfer tax rate on certain kinds of housing in Finland in 2013. And you were able to use that change to test the hypothesis that higher transfer taxes lead to lower mobility rates. Before we talk about those changes, the structure of housing ownership in Finland is interesting and worth learning a little bit about and as you said, you know, the homeownership rate really does matter here for mobility and how transfer taxes affect them. I'd be curious to hear just what the ownership rate looks like in Finland but also, there's an interesting thing here, where unlike the US all owner, occupied multifamily housing in Finland is cooperative ownership, not condominium. And so what is the what is the difference there? And what does the emphasis on coops actually mean for Finnish households in a sort of practical day to day terms?

Tuukka Saarimaa 16:51

So yeah, this this is, this may be just a terminal terminology issue, because we're kind of like, unsure how to translate the system that we have into English. So why don't I explain the Finnish case, and then you can tell me whether that's actually exactly the same as you have in the US.

Shane Phillips 17:06

So I mean, we do have coops here, too. They're just like, only in New York, pretty much.

Paavo Monkkonen 17:11

There's a very separate, there's like one in Santa Monica. They're pretty rare.

Tuukka Saarimaa 17:16

Yeah. So in Finland, all residential buildings with with multiple housing units are legally set up as housing cooperatives or housing companies. That was the alternative translation that we talked about using so the idea here is that the coop, they own the building, and sometimes they have multiple buildings in the same lot. And they, in some cases, they own the land as well, sometimes they rent it from the city. And when you're buying a housing unit, in a housing co-op, you're buying shares in the coop that correspond to a particular housing unit, and owning the shares in practice implies that you own the unit. So you can either live there yourself, and then you're a homeowner or an owner occupier, or you can rent it out to some other household, and then then you're a landlord. So that's the way it works, and these coops often have what's also relevant for the reform here is that they often have outstanding loans taken out for, for example, during the construction period, or because of some major renovation done later on to the building, and then these loans are allocated to the, to the shares, and the owner of the shares is then responsible for the corresponding portion of the loans interest payments and repayment and so on.

Shane Phillips 18:34

Paavo, that sounds to me like coops here, because condos, you actually own the individual unit and coops you just own sort of a share in the building that sort of represents your unit and gives you the right to use your unit, but it's not the same as owning the unit itself.

Paavo Monkkonen 18:51

Yep, I think that's exactly correct. I mean, you know, the practical implication for the US is I think condos are easier to get a mortgage for I think we don't have a good financing system yet set up to buy co-op shares, you know, not as good as the condo but that's more as a problem with their housing finance system. I guess, maybe even the bigger difference, though, is that, if I understand correctly, in Finland, most multifamily buildings are owner-occupied, rather than owned by one entity and have the units rented out. Is that the case?

Tuukka Saarimaa 19:23

Yeah, and then they're also mixed, kind of like you have some owner occupiers and some renters living in the same building.

Shane Phillips 19:30

What's the homeownership rate?

Tuukka Saarimaa 19:32

So roughly 60% of households and roughly 70% of individuals are owner occupiers and then slightly more than half of those are in single family houses.

Shane Phillips 19:44

It's amazing how consistent that is, you know, the US is 65%, France is 60%, Finland 60%. Canada's probably right in that range to despite pretty different, you know, policies. around all this stuff. So now let's actually talk about the tax reform, what was the tax reform, and what was the government's rationale for making the change that they did?

Tuukka Saarimaa 20:10

So the tax reform increased the tax burden on these apartments in these coops, while the tax treatment of single-family houses remained unchanged. So until the end of February 2013, the transfer tax rate was 4%, for houses and remained four 4% for single-family houses, and it was 1.6% for the apartments in coops. And in both cases, the tax base then was the transaction price. Whereas after, you know, March, the first of March in 2013, the transfer tax for apartments the tax rate was increased to 2%, and at the same time, the tax base was brought in so that it would include any outstanding core blown, assigned to that department

Shane Phillips 21:00

So not only did the tax rate go up by point four percentage points, but also the value being taxed on a sale was often higher, because it now included these, the loan balances

Tuukka Saarimaa 21:13

Yeah, exactly, and I guess the rationale for the reform was mostly fiscal, so they wanted to collect more taxes, and they had an idea that, you know, people really don't care about transfer taxes. When they're thinking about moving, they move anyway. And this is such a small tax, that it doesn't really matter. And the other rationale was make the tax treatment of these two different homeowner types more similar so they were increasing the tax rates would be more similar. But they were also going to like directly worried about, so we had a phenomenon and it's still going on that these coops, especially new buildings, they had really high go up loans. And people thought that one reason was that that that makes the tax base for the first buyer really low, and people are saying that that's because of the tax. So let's, let's increase the door wide and broaden the tax base or get let's get rid of that incentive. But I think that hasn't changed the amount of loans that these coops have.

Shane Phillips 22:18

Only one way to find out if that was the reason the loan balances were so big.

Paavo Monkkonen 22:22

I'm surprised. I'm surprised that the transfer tax isn't progressive given that, you know, I don't know if it's still true but I think like even speeding tickets are tied to income levels in Finland right? So I'm surprised that it's not a progressive rate, based on the value of... was that not part of the conversation?

Tuukka Saarimaa 22:41

Not that I remember, I don't think that we talked about that.

Shane Phillips 22:44

Okay, yeah, and just so folks are know what that means, that just means a higher rate on higher value sales. So like, if it's a $200,000 home, maybe it's 2%, if it's a $500,000 home, maybe it's 3%, that kind of thing.

Paavo Monkkonen 22:58

You mean, if it's a $5 million home?

We'll get there.

Shane Phillips 23:04

So now that we understand this policy context a little bit better, can you tell us more about the research design that you use, specifically, tell us about your interest in the potential for spillover effects, and what that means? And how you address it in a way that other studies haven't been able to or maybe haven't thought to? And it might make sense to mention, really the quality and the breadth of the data on Finnish households here too.

Tuukka Saarimaa 23:30

Yeah, let me start with the data. So we use population, wide individual registered data from 2005 to 2016 so we have multiple years before the tax reform and multiple years after. So the data includes information on individuals' incomes, education level, family structure, and so on, and we also know the housing unit for each individual at the end of each year in the data. And crucially, we know whether the household is a renter, whether they are owner occupiers whether they live in coops or in single family houses so we can assign all individuals into a treatment or a control group here. So okay, so ultimately, what we want to know here is that so what happened to the treatment group, which is the apartment owners here, if there was no tax increase, and then we would want to compare this to what actually happened to the same group, and then the difference would be the causal effect that we that we're interested in here. But obviously, here's the problem here is that we don't observe this counterfactual for the treatment group and they're not treated.

Shane Phillips 24:36

Right

Tuukka Saarimaa 24:37

So the idea of the design here, the definitive design is that, that we use the control group as the kind of like the missing counterfactual. So in the absence of the tax increase, mobility in the treat treatment group would have developed in the same way as it did in the control group. That's kind of like the assumption that we're relying on here. And we can test this assumption indirectly by looking at what happened, you know, before the treatment, so by showing what happened in treatment and control groups before the reform, whether they developed similarly, or whether they had common trends before the treatment kind of like allows us to indirectly test whether that that that assumption is true or not. But at the same time, I'm coming to the spillovers here, this design works only if the control group is not indirectly affected by the tax reform. So if homeowners in the treatment group living in the apartments in the co-ops move less often because of the tax increase, then maybe the homeowner is also in the control group are indirectly affected, because they have less trading partners to interact with. So households in the treatment group are less likely to be less willing to move now so maybe that affects, you know, whether the better the control group households can find

Shane Phillips 25:53

There might just be fewer, fewer homes on the market. Apartments specifically for them to move into.

Tuukka Saarimaa 25:56

Yeah

Paavo Monkkonen 25:58

People move between groups.

Tuukka Saarimaa 26:00

Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

Shane Phillips 26:01

You don't have house people and apartment people, and they never mix.

Paavo Monkkonen 26:07

Yeah.

Tuukka Saarimaa 26:07

And of course, this might be a problem, you know. So do you think this estimate in this case will be biased toward zero because it will be a combination of the true effect and the spillover effect, and the spillover effect is now the indirect effect of reform on homeowners in the control group. And I guess the key contribution of our paper, because there have been other papers on transfer taxes before us, the key contribution is kind of like take this spillover problem seriously and try to quantify the bias caused by this, the spillover effect. And we can do this basically, because our data is so good that we can actually see you know, move between the treatment and control groups, before and after the reform so that we can first of all, show that it's true that people move from, from single-family houses to apartments and vice versa so there's a potential for this problem here. So that's one thing so a lot of the other papers have used transaction data so not data on household mobility, but rather how many transactions take place. And in in those cases, you usually don't have any information on these potential spill overs, it's impossible to observe, you know, whether there's even potentially a problem there. So I'm not going to go into the details here, it's a modeling exercise that we do here so we use the information that we have in the data, on these on these mobility rates across the different housing market segments, and also our definitive estimate that we get by running the usual definitive estimation there. So we kind of like putting these pre-reform mobility rates across different groups into the model and our definitive estimate, and in a sense, we ask the model to tell us, you know, what happens to the mobility rate in the control group, given these numbers that we kind of like put into the model, and then we can, in a sense back out to the spillover effect using using this approach. This is, of course, not a perfect approach, but...

Shane Phillips 28:09

...they never are. Yeah, so what did you find? What was the impact on mobility of the tax increase for the treatment group for the apartment owners and sellers and buyers? And then what did it look like when you included the spillover effects into the house market not just the apartment market?

Tuukka Saarimaa 28:28

Yeah, so for some basic numbers here. So before the reform, the annual mobility rate in the treatment group was roughly 7.5%. So in other words, 7.5% of the homeowners living in these apartments moved during a given year. And so what we found was that the mobility rate decreased in this treatment group because of the tax tax increased by roughly 7.2%, and this estimate takes into account the spillover problem here. And then what happened to the control group, what we find is that the spillover effects are are important, it's important to take them into account. So we found that due to the tax reform, the mobility rates decreased in the control group by some 1.6%.

Shane Phillips 29:17

So it's higher for the the treatment group, the apartment owners, and there is also an impact on the house owners got it. Right, right. Hey, this is Shane coming in. After the recording. I wanted to insert a little more explanation here because I realized that even as I was re listening to this, I was having some trouble understanding exactly how this was done and why this was different from the traditional approach. The difference in difference calculation Tuukka is referring to hear the diff in diff is the difference between the change in mobility rates for apartment owners and the change in mobility rates for house owners following the tax increase on apartments sales. So it's the difference between those two differences in mobility rates. If a reduction in mobility for apartment owners also reduces the number of trading partners for house owners, such that house owners move less often than the difference between the two will actually be smaller. And it will make the impact of the tax seems smaller as well. In Tuukka's and his colleagues research, they found that mobility for apartment owners fell by 7.2% but mobility for house owners also fell by 1.6%. The difference between those two changes in mobility rates, the diff in diff, is 5.6%. He's making the point that the gap between the changing apartment owner and house owner mobility rates doesn't tell the whole story, because they both fell. And there's good reason to believe that they both fell because of the tax increase. Usually in this kind of diff in diff analysis, you would say that the impact was just however much more or less the treatment group, which is the apartment owners whose taxes went up changed relative to the control group, which is the house owners whose taxes didn't change. But that doesn't make sense here because the impact is spilling over into the control group. The spillover is the 1.6% reduction that's affecting both the apartment owners and the house owners, in addition to the 5.6% reduction that's affecting only the apartment owners. Okay, back to the interview.

Paavo Monkkonen 31:27

Tuukka that all sounds pretty convincing but I'm worried about potential threats to validity of this kind of research. Were there concerns you had in your study? I mean, there anything interesting you'd like to point out in terms of issues that you I mean, in addition to this spillover consideration, what else might have might have made these estimates a little bit off?

Tuukka Saarimaa 31:47

Yeah, so the problem here would be that, you know, if something happened, exactly at the same time, as the tax reform, that affected the groups differently, then we will have a problem. And, you know, it's hard to tell whether, whether, you know, any definitive analysis has this problem, but at least we can say that we are not aware of any other major policy changes coinciding with the tax reform that would affect housing markets, and especially whilst that would affect the treatment and control groups differently, right. And also, I think that, since we have so much data before the reform, although going back all the way to 2005., and we can show that the mobility rates in treatment and control groups, they follow each other quite nicely, even during the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009. So we're kind of like, that's pretty convincing evidence of this assumption that, although this is not direct evidence of saying that nothing else could have happened at exactly the same time as the tax reform, but..

Paavo Monkkonen 32:55

And the fact that you don't use transactions, I mean, did you consider, you know, are people suddenly moving without selling much more than they had before?

Tuukka Saarimaa 33:05

Yeah, this would be an interesting thing to look at but unfortunately, we don't have...

Paavo Monkkonen 33:09

I wouldn't imagine it's a huge problem.

Tuukka Saarimaa 33:10

Yeah, probably not. Yeah. so currently, we don't have this type of data so we don't have asset ownerships for these people in the data so we don't know whether they end up kind of like owning their old apartment once they move.

Paavo Monkkonen 33:25

How about timing? I know, you looked at this as well, that maybe people are they knew that the tax increase was coming, and it was actually even delayed by a few months so maybe they tried to sell their home before to kind of evade that tax or get out ahead of it. What did you find there because, as I said, you did look into that.

Tuukka Saarimaa 33:44

Yeah, so we cannot look at that using our household data, because we only observe people at the end of the year. But we have monthly level data on overall transactions in these different groups, and what we find is that there's a really clear, kind of like, people anticipate reform, they really sell, you know, just a couple of months before the tax increase, and there's a huge increase in transactions, and then after the reform, there's a clear reduction, but then it comes back to kinda like,

Shane Phillips 34:14

Which I gotta say, seems like 0.4% percentage point tax increase, it's kind of surprising that people are making this huge decision. I mean, I'm sure many of them had already been thinking, like, I think I'm going to sell at some point, I might as well push it up but it's, I don't know, I guess, point 0.4% still adds up to this hundreds version, you know, thousands of dollars in many cases so it's not nothing.

Tuukka Saarimaa 34:36

Yeah but it's pretty easy to kind of like just, you know, bring the sale forward for a few months. That's easy, but I mean, what's more surprising is that the actual mobility results that we that we find,

Paavo Monkkonen 34:48

Yeah, they're pretty large. What about in addition to the kind of this overall effect of the tax, you know, you are able to look into several more specific impacts including welfare and labor market outcomes as well as how, how big of a house, the move people were thinking to make was affected by the tax differences between households that were upsizing downsizing. I didn't know Shane, I thought the most interesting outcomes were on this kind of how far people are moving. And whether this tax had a differential impact on short moves, versus long moves, as well as kind of moves to much bigger houses or moves to much smaller houses. Maybe Tuuka, if you want to tell us about the findings on those two first and others that you found interesting.

Tuukka Saarimaa 35:31

Yeah, so the labor market question, like you said, there's a lot of talk about labor market effects of the transfer taxes in a lot of countries. So it was interesting, but we also, our initial idea was that, that we were expecting to see, you know, close to zero effects for these moves that are related to labor markets, because it seemed to us that labor market rate moves are kind of like more valuable to households compared to moves that happen because of relocating within a city or like doing a size adjustment unit so we were thinking that people would not turn down like job offers, or...

Paavo Monkkonen 36:13

I'm not going to move to that new job in a new city because of this additional $5,000.

Shane Phillips 36:20

And it's not $5,000 when we're talking about an additional point four percentage points.

Paavo Monkkonen 36:26

But even you know, yeah, it'd have to be a lot of money to,

Shane Phillips 36:28

or a very, very minor job upgrade yeah.

Tuukka Saarimaa 36:33

Yeah, and we do find that, you know, so we're looking at moves that are more than 50 kilometers, or less than 50 kilometers, that's an ad hoc, kind of like, I don't know where that threshold came from but you know...

Shane Phillips 36:49

Sounds good

Tuukka Saarimaa 36:49

Yeah, so what we actually found was that, "okay, the effect is smaller for these longer moves, but they're still in effect". So we cannot rule out that transfer tax actually has labor market effects as well but they are small, collective effects on moving is much smaller than than on moves that happen, kind of like within a labor market or within a city

Paavo Monkkonen 37:11

Interesting.

Shane Phillips 37:12

And then you have a finding about how transfer taxes seem to affect upward moves, meaning moves when people buy larger or more expensive homes, but not downward moves to less expensive or smaller homes. In the model researchers have of how people move, and this was kind of news to me but it makes sense, there's this asymmetry between upward and downward moves. Basically, people move multiple times throughout their lives, but they tend to make smaller, more incremental upgrades to their housing or to their neighborhood quality each time they move up, but they might only downsize once or twice in their lives, you know, closer to the end of our lives, presumably all at once. Could you talk about that and why, and increased transfer tax might affect upsizing but not downsizing?

Tuukka Saarimaa 37:58

Sure, so I guess this relates to the concept of a housing career. So I guess a typical housing career might be that, first you get married, then you have a child, then maybe a few years later, you'll have another child, and so on. And while your family is growing, the need for housing space increases as well. And people usually upsize as their family size increases. But things may change when you introduce a transfer tax to the picture here. So instead of upsizing kind of like one bedroom at a time, it could be that you upsize two bedrooms at a time so that you don't have to move as often - you get to avoid one, transfer tax payment by doing that. So maybe you live longer in a small apartment with one child and then buy a much larger house where you can fit your whole kind of like, family or you upsize when the second child is born, and not when the first child is born

Shane Phillips 38:53

Or maybe yeah, like upsize a little early before you really need the extra space yeah!

Tuukka Saarimaa 38:58

That's yeah, exactly. Whereas when you're downsizing, then these moves, they may be more often related to different types of unplanned events like a divorce or unemployment or death of a spouse, where you might think that these tax incentives don't play as big of a role as in this when you're moving up the house.

Shane Phillips 39:21

It's not exactly voluntary, either way so you just do it.

Tuukka Saarimaa 39:25

Yeah, I'm not saying that this is the correct story but this is at least consistent with the findings that we have here.

Shane Phillips 39:31

And i think, you know, in cases where it's not involuntary, you know, it's not a divorce, it's not the death of a spouse. Maybe it's just like you're an empty nester couple and do just want to downsize, and I think in that case, you've owned your home probably for a long time, you probably have quite a few resources compared to the average person, and your new home is going to be less expensive than your old one probably so the idea that like this tax is going to deter you from that just doesn't make as much sense. So you also estimate how the transfer tax increase impacted welfare, which economists used to refer to the general welfare of society rather than the way the word is often used in the US, to mean basically government support. And you find that the overall impact is negative, basically, that the reduction to welfare is greater than the increase in revenues, euro for euro. But what I wasn't really clear on is how you arrived at the change in welfare itself - what that calculation look like so I'd like to hear you talk about that. But just to kind of expand on this first, welfare to me seems to be a very encompassing concept, and so it should take into account the negative impacts to mobility and housing consumption, but also the positive impacts of the revenues raised by the increased taxes, the things that that revenue will be spent on. And I think where I'm struggling with this is that a higher tax might lead to fewer moves, but you know, the quality of life benefits of that move might be pretty marginal, I think, in fact, they would almost have to be if such a small tax increase, were to discourage someone or stop someone from moving. But on the revenue side, those euros might help someone who is homeless get back into housing, or help a very poor person pay for rent or food, and those seem to me to have much greater value, even if the dollar or euro value is the same. And I guess I'm getting into kind of philosophical territory...

Paavo Monkkonen 41:30

It sounds like utilitarianism

Shane Phillips 41:32

Yes, about that, we're talking about the marginal utility of money and how $1 means a lot more to a poor person than a rich person, which we don't need to go down that road. But I'd just be curious to hear a bit more about the limitations of this metric, and maybe that can lead us to some other discussion of the benefits and costs and trade-offs of transfer taxes.

Tuukka Saarimaa 41:53

Yeah, sure, so this might be a little bit difficult to unpack but so first of all, the welfare loss here is simply the fact that, you know, the example that I gave earlier of the buyer and the seller, we're now foregoing on like these mutually beneficial trades because of the transfer tax so that's kind of like basically the welfare effect here. And I guess the number here that you're talking about, or the metric, it's most useful when we're actually comparing different ways of collecting the same amount of tax revenue. Okay, so let's take the amount of tax revenue as given, and let's think about what are the different types of types of tax instruments that we can use, and then compare the welfare kind of like these welfare losses from these different types of taxes. So it's kind of like, useful in this, like a more limited sense.

Shane Phillips 42:52

Well, I can also understand that, you know, I can say, well, if you spent those revenues, helping a homeless person, that's going to have more value, but like, for one, I don't know that that's how that money is going to be spent. It's all kind of just part of the government budget, and so it's sort of cherry-pickingng a little bit to say it that way. I think thinking about it in terms of how does this way of raising that amount of revenue versus that way is a really helpful way of thinking about it. Paavo you had something?

Paavo Monkkonen 43:18

No, I was just gonna say, yeah, it's not a total cost benefit analysis. It's just comparing different kinds of costs.

Shane Phillips 43:24

Okay.

Tuukka Saarimaa 43:24

And usually, if we think about, you know, in economics, we usually think that a good tax is such that it doesn't affect the behavior of the taxpayers, or that it should affect the behavior as little as possible. You know, of course, we have corrective taxes, like you know, taxes on negative externalities that the whole idea is we want to affect behavior, but when we have, like taxes, where we just want to have, you know, tax revenue, then we kind of like think that a good tax is such that it doesn't really affect the behavior of the taxpayers. And I guess the underlying assumption there is that that people are kind of like the best judges of what they want to do. So if some people want to move, and then we put a tax in place, which prohibits that move then we argue that that family would have been in a better situation if they actually had made the move.

Paavo Monkkonen 44:24

So we are going to talk about land value tax?

Tuukka Saarimaa 44:28

Yeah, so if I bring another point home here by comparing the transfer tax to a property tax, or a land value tax, so a well designed property tax, like a land value tax, is like a lump sum tax, meaning that this is again a bit of economic jargon here, but it means that the property tax on land does not affect the behavior of the landowner. And this is because you know, whatever the best use of the land was before the property tax, it still is the same after the tax is introduced. Let's say that you have a landowner who thinks that, okay, the best use for my land here is to build a multi-storey building here of a particular size, then the government just says that, "oh, you have to pay, you know, 10,000 in property taxes based on land value", there's nothing you can do about it because if land value is not decided by the landowner, if it's decided by, you know, markets There's nothing that the landowner can do here to avoid the tax so it's still the best option for him to build that same size building.

Shane Phillips 45:37

Because the tax is on the land, and not the improvements, not on the build so no downside to them to building that structure yeah. You talked about distortion earlier, and I did want to ask this question about, you know, in a way the transfer tax, as it was prior to the 2013 reform was already distorting, because it was a higher tax on houses - detached homes, as opposed to apartments, multifamily units. I mean, could it could this be seen as a way of just rather than reducing welfare, but actually reducing the distortion that was there? And I say this as someone who generally thinks we should actually tax detached homes at a higher rate because they do have some negative externalities relative to multifamily but like, is that a reasonable way of thinking about this or am I missing something there?

Tuukka Saarimaa 46:28

No, no, I think that's that's completely right. So you can think about the reform as kind of like bringing the tax treatment of these two building types closer together. So there's probably no good reason to have separate tax rates for apartments and single family houses. At the same time, I would say that I would favor a revenue-neutral tax reform where you'd have to have the same tax rate on these apartments and single-family houses, but you wouldn't increase the overall tax burden or the tax revenue that you raise rates to transfer

Shane Phillips 47:01

You actually lower the tax rate on houses.

Tuukka Saarimaa 47:04

Yeah, yeah.

Shane Phillips 47:06

I'll have to side eye at that, I'm not sure I'm on board with that one.

Paavo Monkkonen 47:12

Tuuka I'm so curious, was gonna ask it earlier but I think now's a good time, about kind of the general package of property-related taxes in a city like Helsinki, so how high are property taxes, and are they calculated based on land and improvements, and are development taxes widely used as well, so kind of requiring developers to fund public services when they when they apply for a permit?

Tuukka Saarimaa 47:40

So in general, property taxes are collected by the municipalities, which is the local level, but the transfer tax is collected by the central government. So that's one one important thing here

Shane Phillips 47:51

Like the reverse of the US in some respects.

Tuukka Saarimaa 47:54

So property taxes are pretty low in Finland, they have been increasing over the years here. We have a separate tax rate that applies to land, residential lots, and a separate tax on buildings, and we are actually now introducing a pure land value tax in the coming years, because the correct land value tax, that tax rate also applies to business properties, business buildings, so currently, you're not able to increase the property tax on land without increasing the property tax on business buildings as well. But that's gonna change shortly. So what was the rest of the question?

Paavo Monkkonen 48:34

Is there a tax a widely use tax on development Meaning, if a developer wants to build a building, do they have to pay for public services?

Tuukka Saarimaa 48:43

Not a tax per se..

Yeah, not a tax that you always would have to pay but municipalities kind of like they are allowed to make these deals that there is a fee involved if you want to kind of like develop a land, and that is municipality specific so there's no general

Shane Phillips 49:02

Sounds like impact fees, like we have here, basically.

Tuukka Saarimaa 49:05

So I guess the important thing here about transfer taxes and property taxes is that, so it might be difficult to kind of like, "oh, you want to lower the transfer tax and increase property taxes" but it's difficult. Yeah, the coordination might be difficult.

Shane Phillips 49:18

Yeah, well, and I think just people, in my experience, have more negative feelings toward property taxes, just as a general rule than they do toward transfer taxes, maybe because they're just not super familiar with transfer taxes but I think the fact that transfer taxes only hit once you know, on the time of sale, you might sell multiple times in your life, but it's not this year after year thing. I've come to appreciate that it's like property taxes and gas taxes are the two that people are the most irrational about, and they hate them, no matter what they never support them going up.

Tuukka Saarimaa 49:52

Yeah, I've noticed.

Shane Phillips 49:55

So we started to talk about, you know, alternatives and welfare and all of this, and you find that transfer taxes have this negative impact on mobility, and because of that they also negatively impact welfare in some important ways. But there are better and worse kinds of taxes as that that cost of public funds ratio that you alluded to measures, and all of these different kinds of taxes have costs. So do you think transfer taxes makes sense if alternatives like land value taxes, like property taxes more generally, are maybe nonstarters politically or in the case of California here, unconstitutional without, you know, a statewide ballot initiative? And in addition to that question of do they make sense as alternatives, are there ways to limit some of these unintended consequences, whether reduced mobility or otherwise?

Tuukka Saarimaa 50:51

So I guess if your hands are really tied in terms of what tax instruments you have at your disposal, then you have to collect some taxes then obviously, you need to tax what you can and I guess the...

Shane Phillips 51:05

Have to is always, you know, questionable, but like, often have to, yes.

Tuukka Saarimaa 51:11

Yeah, and this is, by the way, probably one of the reasons that we actually have a transfer tax in the first place, because it used to be the most easy way to tax people, you know, compared to wealth for example. It's easy to measure, you can see the transaction taking place, you can see the price, and you can tax it. But, for example, it's much more difficult to estimate the value of wealth or even measure income correctly, or something like that

Shane Phillips 51:36

And to collect it, because if someone has all their wealth in stock, then you can't really force them to sell it, or people don't really like to do that. Or if it's all in fancy paintings, like, you know, it's just hard to actually assess and collect the taxes compared to transfer taxes, because like, there's a bunch of money trading hands right at that moment.

Tuukka Saarimaa 51:57

Yeah, but I guess that's kind of like, that used to be the case. I think that with current technology with income taxes, and consumption tax like the value-added tax that we have in Europe, you can kind of like have more efficient taxes that you can actually collect pretty easily.

Paavo Monkkonen 52:15

I wonder do you think people think about this as a wealth tax, or kind of part of a redistribution model of approach to taxation or is it just a pragmatic way for the government to get more money?

Tuukka Saarimaa 52:28

To me, it seems like it's a pragmatic way to get get more money.

Paavo Monkkonen 52:32

Yeah, okay, interesting! Yeah. I mean because if it were thought of in a kind of wealth tax sense, then you would want to have a progressive rate to tax wealthier individuals yeah.

Shane Phillips 52:43

And how about the different ways of structuring this? You know, I guess I'll mentioned here in LA, I said at the beginning that we have this ballot initiative that we're going to be voting on in November. And that would increase transfer taxes only on properties valued over $5 million, or $5 million, and up, and I will say, although I support that initiative, I do think that threshold is way too high. But one feature of that approach is that it won't affect the vast majority of homebuyers and homesellers, even in a place as expensive as LA, it's really going to be limited to, you know, the ultra-luxury single family homes, and then apartments, basically, and commercial properties and so forth. So do you think that approach is superior overall? Or is it maybe just ultimately trading one set of costs and benefits for a different set of costs and benefits?

Tuukka Saarimaa 53:34

Yeah, so I'm not super familiar with LA case but I guess in general terms, we economists tend to think that we should have, you know, broad tax bases with very little kind of like exemptions and low rates. So that would be the way to go here instead of having, you know, a lot of exemptions, you know...

Paavo Monkkonen 53:56

And that's what, you know, when we when Professor Manville and I get together and talk about the costs and benefits of different tax structures...

Shane Phillips 54:03

As you do.

Paavo Monkkonen 54:06

You know, the way I frame it is, you know, if you think about taxes on development, you're going to raise much less money because the base is so narrow. Well, then you talk about taxes on transfers, you're expanding the base considerably because there's many more sales than new buildings being built. But then in property tax, right, that's the ideal because the land value tax because the base is every property, right?

Shane Phillips 54:27

Yeah, I like that way of thinking about it. And I will say, our buddy, Councilmember Alex Fisch, helped author a Ballot Initiative for Culver City for 2020 that they did pass the increased transfer taxes in a progressive way on properties worth $1.5 million or more. And I think the initial estimate, at the time it was drafted, was this would raise about $8 million a year but in fact, there have been a few very large sales of you know, $500 million properties or something just For the past several months, and so this tax that was supposed to raise 8 million a year, and maybe it will consistently do that by, you know, with the sale of these one and a half million $2 million detached homes, but because of those giant sales, it's raising like 20 something $30 million in this year alone. It's sort of the you've got the broad base to rely on but then you get these giant spikes at times, which is you know, extra money and for a city of what 30,000 people, an extra $30 million can go a long way. Well, as we close out here, Tuuka, I want to give you the opportunity to let our listeners know if there's any way they can find you or you know what you're working on. But I did want to....

Paavo Monkkonen 55:43

.... mention your other cool paper.

Shane Phillips 55:45

This is what I just wanted to make sure, I haven't even read it in detail, I've only skimmed through it but it's maybe the best title of a paper I've read in a long time. It's called, "I don't care to belong to any club that will have me as a member: Empirical analysis of municipal mergers". I'm looking forward to reading it. It's almost a decade old at this point but I just want to congratulate you on a really excellent title for the article.

Tuukka Saarimaa 56:14

Thank you. That's my only Marxian work, props to Marx.

Shane Phillips 56:21

Nice!

Paavo Monkkonen 56:23

But I was gonna mention the you also did a residential moves estimate of the impact of new housing construction on the city. In the spirit of Asquith and masks, I would point people to that paper as well.

Shane Phillips 56:37

Using the same data, right?

Tuukka Saarimaa 56:38

Yeah, oh, even actually better. Now, we have better location data that we were able to be able to use in that paper so.

Shane Phillips 56:45

All right, well, Tuukka Saarimaa. Thank you for coming on the housing voice podcast.

Tuukka Saarimaa 56:50

Thanks for having me.

Shane Phillips 56:55

You can read more about Tuukka's research on our website. lewis.ucla.edu. Show Notes and a transcript of the interview are there too. The UCLA Lewis Center is on Facebook and Twitter. I'm on Twitter at @ShaneDPhillips, and Paavo is at @Elpaavo. Thank you for listening. We'll see you next time.

About the Guest Speaker(s)

Tuukka Saarimaa

Tuukka Saarimaa is an assistant professor of urban economics at the Aalto University's Department of Economics and the Department of Built Environment, and a professor at Helsinki Graduate School of Economics. His research focuses on housing and urban economics, and local public finance.Suggested Episodes