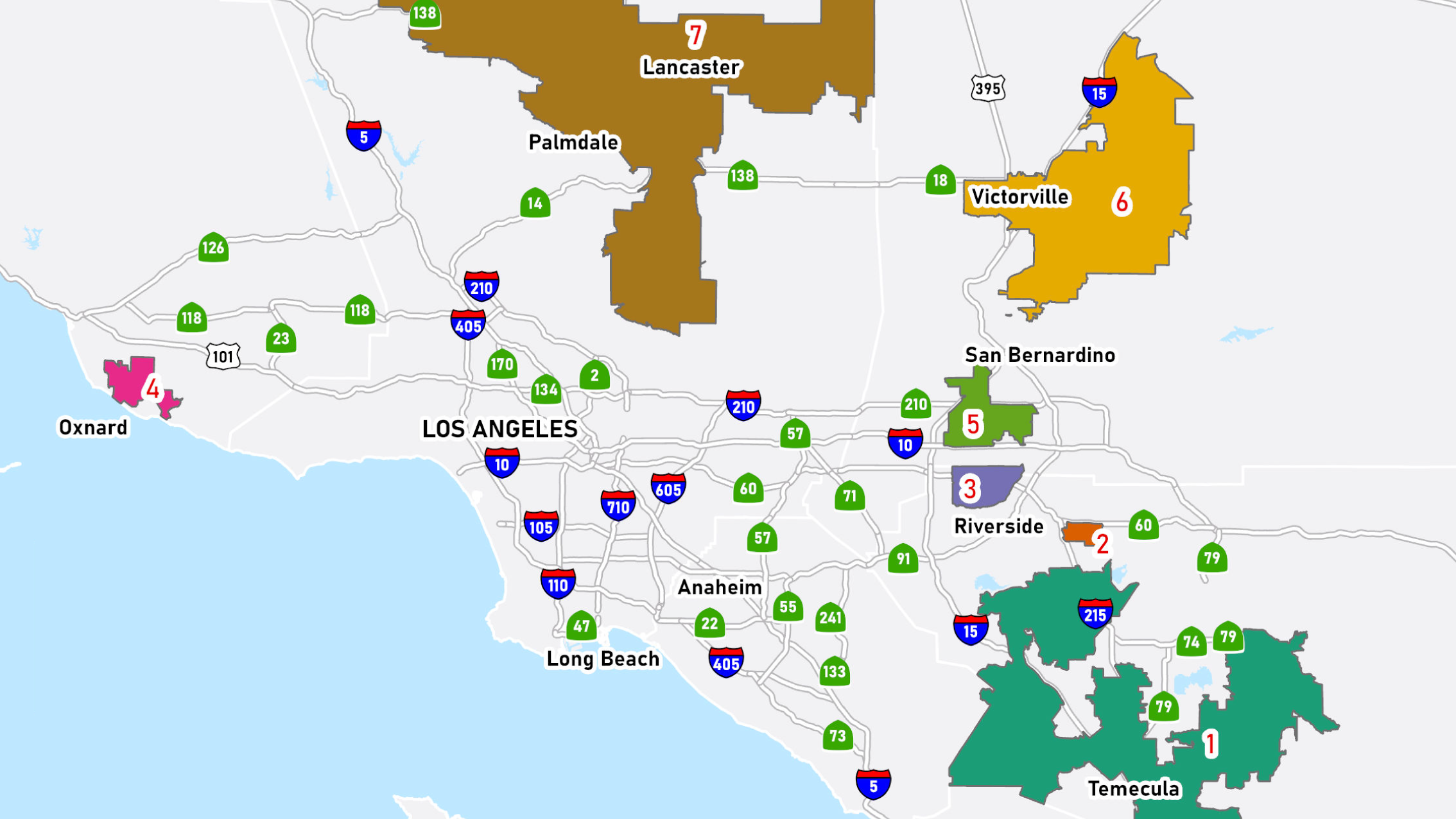

UCLA scholars publish reports on future of California housing, transportation

California faces a housing crisis of extraordinary scale that has led to high rents and home prices, displacement, overcrowding, and homelessness.

Long commutes have also put a strain on the state’s transportation systems with chronic congestion, falling transit use, worsening emissions and noise pollution, heightened vulnerability to climate change, and more.

To help envision a better future for the state, UCLA researchers recently released two reports on the future of housing and transportation, made possible by a grant from the California 100 initiative.

Spearheaded by the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies and the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies, they examined where California has been, where it’s at and where it’s headed when it comes to possible scenarios and policy alternatives for the future. In each report, one scenario is the clear preference – though not necessarily the easiest to bring about.

For transportation, that’s a future where it’s easy to get around without a car. Driving will still be the norm in rural areas, though less common in suburbs and increasingly rare in city centers, where access to housing, jobs and other amenities is within walking distance.

According to Brian Taylor, UCLA ITS director, a resistance to change and distrust in government will make the work difficult.

“Try things out,” Taylor said during a March 29 release event. “Don’t wait to get everyone’s approval. Just try small, pilot projects and come back to people to see what they think.”

California 100, incubated at the University of California and Stanford University, released its first four issue and scenario reports on March 29. The housing and transportation reports were published in concert with the future of energy and technology in the golden state. In July, the initiative announced grants to 18 centers and institutes across California to examine future scenarios with the potential to shape California’s leadership in the coming century. In total, UCLA organizations spearheaded three of the 13 priority research areas. The remaining 9 research reports will be released in the coming months.

The Future of Housing and Community Development

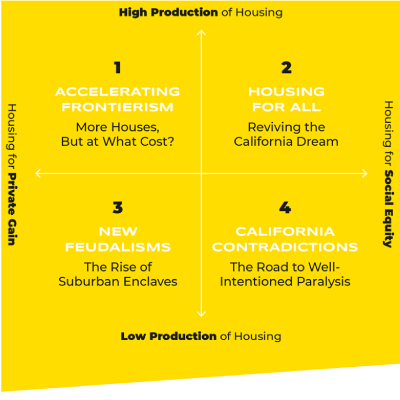

The Lewis Center, along with cityLAB UCLA and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, proposed four alternative scenarios based on decisions made along two interrelated factors – how much housing we build and where, and how deeply we value and prioritize social and racial equity.

The Lewis Center, along with cityLAB UCLA and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, proposed four alternative scenarios based on decisions made along two interrelated factors – how much housing we build and where, and how deeply we value and prioritize social and racial equity.

Carolina Reid, faculty research advisor at the Terner Center, said during the release event that a future that provides housing for all will require the state to prioritize housing supply and social equity equally – by focusing on renters, continuing to remove barriers to new housing, and addressing racial discrimination.

“The path to a more sustainable future is straightforward, but not simple,” she said. “It’ll require a fundamental shift in how we prioritize public resources, and it’ll require confronting third-rail political issues like Prop 13, CEQA and local land use control.”

Scenario 1: Accelerating Frontierism

As a result of continued NIMBY opposition to new housing in urban areas, California has responded to growing demand with increased production of cheaper houses on the urban fringe. Inexpensive greenfield lands drew developers outward from urban areas to build more tract housing, and would-be owners followed for their chance at homeownership. Homeowners in urban areas and inner-ring suburbs continue to enjoy rising home values, while middle-class households are able to purchase homes in sprawling subdivisions. Yet the expanding frontier of a building boom entrenched an unsustainable pathway forward, not just adding to the climate crisis but accelerating its arrival.

Scenario 2: Housing for All

The deepening housing crisis sparked a public and private social mobilization for housing, drawing connections to the intersecting threats of climate change, widening inequality, and racial disparities. Governments and markets were able to coordinate and create transformative investments in people and the built environment, wielding a variety of resources, incentives, and policies to spur housing production and support residents. These long-term investments in housing, transportation, and jobs have helped the state build resilience to weather future challenges.

Scenario 3: New Feudalisms

In the battle between housing appreciation and housing affordability, property values won. Scarcity — not just of homes, but of government support, tenant protections, and public interest — has heightened tensions and driven a deeper wedge between the haves and have-nots. Renters, working class families, and communities of color unable to afford accommodations migrate out of California at an increasing pace, and corporate landlords and investment firms are consolidating their ownership of the homes left behind.

Scenario 4: California Contradictions

California commits to ensuring its existing residents are treated equitably in the housing market, but housing production continues to fall far short of need. Tenant and building protections stabilize neighborhoods, especially for renters and communities of color, and creative accommodations make room for unhoused neighbors as well. Yet limits on new construction maintain a bottleneck on economic growth, curtailing the economy and California’s role as an immigrant gateway.

The researchers proposed a number of policy alternatives for California’s future, including increasing low-density housing in suburban and rural areas, implementing zoning, permitting and building reforms, and establishing housing stability and tenant protection programs, among others. For a full list of policy recommendations, read the report here.

The Future of Transportation and Urban Planning

“Because travel is largely a means to an end, it’s hard to talk about transportation systems without talking about the origins and destinations they link together,” Taylor said.

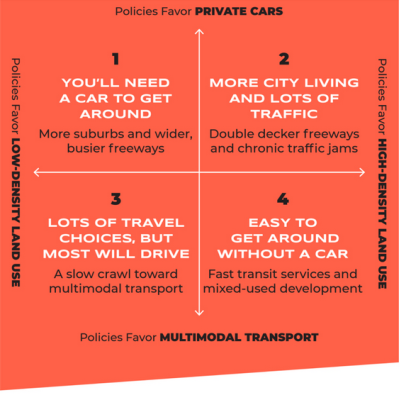

To that end, the UCLA Institute of Transporation Studies planned for multiple futures around the interplay of land use density and transportation options.

Scenario 1: You’ll Need a Car to Get Around

This is the historic norm in California that still describes most suburban areas. Building densities are low, land uses are separated, streets are wide, parking is abundant, and almost every trip is made by motor vehicle for those with cars. Single-family neighborhoods, for those who can afford them, are pleasant, but travel distances are long and many arterials and most freeways are chronically congested.

Scenario 2: More City Living and Lots of Traffic

Development densities increase, particularly in central cities and inner-ring suburbs, raising the supply of housing and affordable housing in particular. But rather than investing in multimodal travel, public officials accede to popular calls to widen boulevards and freeways (even double-decking the most heavily trafficked ones) and build parking decks to store the mass of cars in central areas. Walking increases, but chronic traffic slows both cars and buses to a crawl, increases emissions, and prompts further calls for expanded road and parking capacity.

Scenario 3: Lots of Travel Choices, But Most Will Drive

This is the new normal in much of metropolitan California, where transportation investments go increasingly toward walking, biking, scootering, and public transit infrastructure, though most trips are still made by car. Looking ahead, multimodal options continue to expand, while policies to rein in unfettered driving — such as improved and expanded public transit service and pricing driving to reduce congestion and emissions and encourage multimodal travel — are gradually phased in. However, outside of already built-up central cities, most development remains dispersed and housing undersupplied, poorly served by modes other than driving.

Scenario 4: Easy to Get Around Without a Car

This scenario entails the biggest break from current patterns, wherein multimodal-focused transportation policies are combined with the higher-density land use policies. Road and parking access are managed to substantially reduce congestion (making driving both better and rarer) and emissions. Fast, frequent transit service reduces waits and makes riding more attractive. Denser, mixed-use development puts more destinations within walking distance and more affordable housing where it is most demanded.

The researchers proposed policy alternatives designed to increase trust in state government and in a shared vision for California, including instituting changes today prerequisite for the multimodal, higher-density scenario. For a full list of recommendations, see report here.