Episode 02: Mortgage Discrimination with José Loya

Episode Summary: Most of us are familiar with how subprime loans were disproportionately (and predatorily) targeted at Black and Latino households during the 2000s housing bubble leading up to the Great Recession. Less well known is that disparate treatment in mortgage lending is making a comeback alongside the recovery of the housing market. José Loya of UCLA joins Shane and Mike to talk about ethnic and racial disparities in access to mortgage credit in the years following the housing crash. Recorded December 2020

- Loya, J., & Flippen, C. (2020). The Great Recession and Ethno-Racial Disparities in Access to Mortgage Credit. Social Problems.

- Noble, Safiya Umoja. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. NYU Press.

- Phillips, Shane. (February 2, 2021). A “Rental Pension” Program to Compete with Homeownership. Better Institutions.

- Phillips, Shane. (March 11, 2021). Renting is Terrible. Owning is Worse. The Atlantic.

- Rugh, J. S., & Massey, D. S. (2010). Racial segregation and the American foreclosure crisis. American sociological review, 75(5), 629-651.

- Since 2012, the homeownership rate has hovered around 72 percent for non-Hispanic whites, 57 percent for Asians, 42 percent for blacks and 46 percent for Latinos. “For African Americans in particular, homeownership rates were actually lower, and disparities with whites higher, in 2016 than in 1994.”

- “While a variety of economic and social factors contribute to disparate rates of homeownership across groups, differential access to mortgage financing remains a key structural source of inequality. Even with ameliorative policies, such as the 1968 Fair Housing Act and the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act, audit studies continue to demonstrate widespread discriminatory treatment of black and Latino loan applicants, who are both more likely to be rejected overall and more likely to be steered into smaller and higher-cost loans than similarly situated whites.”

- “While black and Latino borrowers have long paid higher costs and enjoyed fewer consumer protections than white applicants, this tendency was exacerbated by the subprime crisis. In 2006, 54 percent of black and 47 percent of Hispanic homebuyers received subprime loans, relative to only 18 percent among whites and 17 percent among Asians. Subprime lending became a tool to lure black and Latino applicants into unfavorable agreements, even when they qualified for conventional and lower cost loans. Moreover, communities of color were disproportionately targeted for infusion of expensive and subprime lending, in a perverse form of “reverse redlining.” At the zip code level, the growth of subprime lending from 2002 to 2005 was negatively correlated with income growth and positively correlated with the concentrations of black and Hispanic residents. There is also evidence that the concentration of subprime credit in minority communities was particularly acute in highly segregated metropolitan areas.

- “The impact of the economic recovery on inequality in access to mortgage credit is equally unclear … As the period of intense oversight over lending standards ebbs, there could be a gradual return to the discriminatory practices of the subprime era. In fact, high-cost lending has been slowly increasing in recent years; a mere 1.4 percent of loans in 2010, the share of loans that were high-cost, rose to 6.9 percent by 2013 and 8.6 percent in 2017. It remains to be seen whether this expansion follows the same ethno-racial and spatial patterns as the subprime boom.”

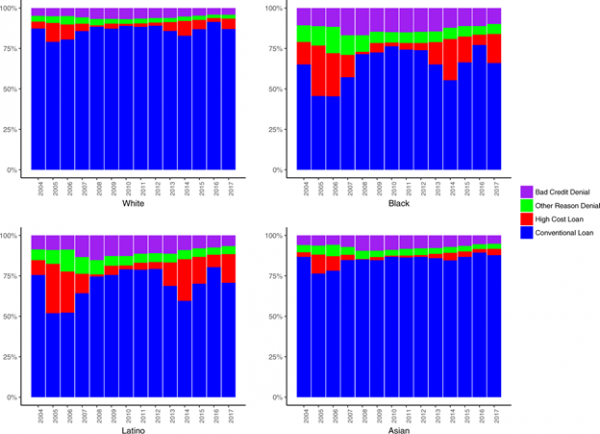

- “The dependent variable for this analysis is the outcome of completed loan applications. There are three possible outcomes to all applications: they can be granted a conventional loan; applicants can be approved for a high-cost loan; or they can be denied.”

- “The figure [below] clearly shows large ethno-racial disparities in application outcomes throughout the period. In every year under consideration, black and Latino mortgage applicants were less likely to be approved for a conventional loan, more likely to be approved for a high-cost loan, and more likely to have their application denied, both due to bad credit and other reasons. Asian applicants fare slightly better than whites on all of these dimensions.”

- “The figure also highlights dramatic short-term shifts in application outcomes for all groups. Not surprisingly, high-cost lending comprised a particularly large segment of application outcomes during the years associated with the housing “bubble” (2004 through 2007) and a much smaller share during the recessionary years associated with the tightest credit (2008–2011). While tightening lending standards meant that some of the decline in high-cost lending resulted in higher rejection rates, particularly for reasons relating to bad credit, the share of applications ending in conventional loan origination rose considerably during the recessionary years. The figure also highlights an upward trend of high-cost lending after 2011, as the economy and lending expanded.”

- “These period shifts, however, show a marked variation by race and ethnicity. During the recession/tight credit years loan rejection rates, both due to bad credit and other/unspecified reasons, increased more for blacks and Latinos than whites and Asians. However, the decline in high-cost loans and the growing share of conventional loan acceptance was also greater for blacks and Latinos, who had much greater exposure to high-cost loans during the bubble. As such, the gap between whites/Asians and blacks/Latinos in acceptance into conventional loans fell slightly during the Great Recession period. The uptake in high-cost lending during the recovery, however, was also larger for blacks and Latinos than for whites and Asians.”

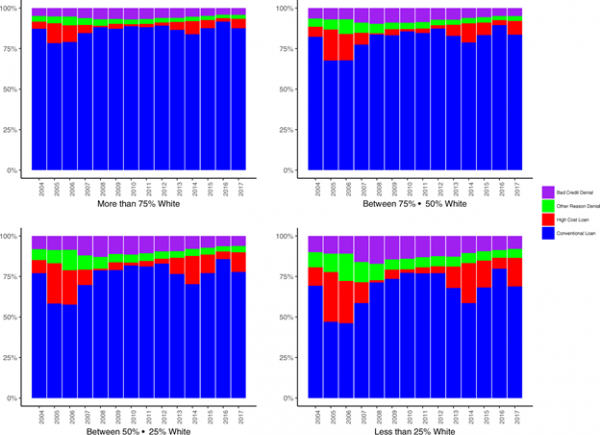

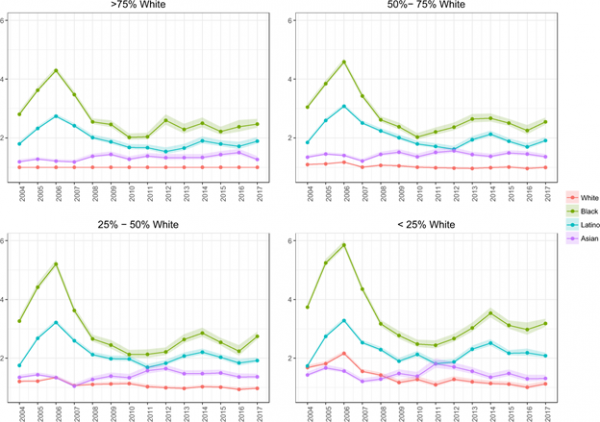

- “Figure 2 displays mortgage outcomes by neighborhood ethno-racial composition over time. The mortgage outcomes in predominantly non-white neighborhoods exhibit similar patterns to those of black and Latino applicants shown in Figure 1. Predominantly non-white neighborhoods absorbed high levels of high-cost loans during the bubble, which declined dramatically during the Great Recession. After 2012 there was a large increase in high-cost loans in all neighborhood types, but the increase was most drastic in those that were 75 percent non-white or more, where the incidence rose from four percent in 2012 to 17 percent in 2017.”

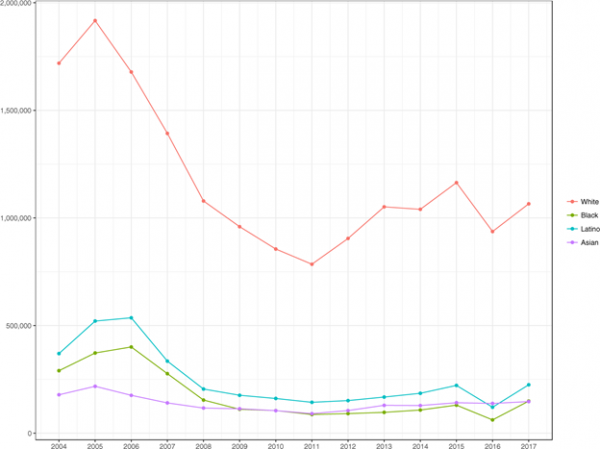

- Figure 3, loan applicants by race. Note that the number of white applicants began to fall in 2006, but didn’t fall for Black or Latino applicants until 2007. Also: “The number of applications remained roughly stable for non-white applicants after 2008, while for whites they began to rebound after 2011. The fact that racial and ethnic disparities in high-cost lending have re-emerged after 2011, in spite of the continued low levels of black and Latino applications, is troubling.”

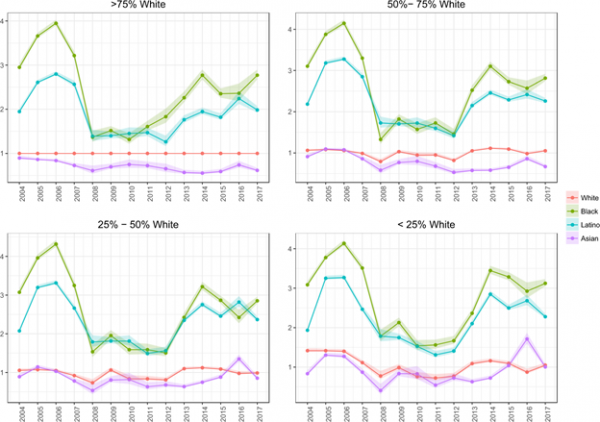

- Figure 4: Odds ratios for high-cost loan origination by neighborhood racial composition

- “Overall, the prevailing pattern is that disparities with whites are lowest in the neighborhoods with the highest proportions of whites. However, the relationship is not perfectly linear, as disparities with whites are often as high in neighborhoods that are between 25 and 50 percent white as they are in communities in which fewer than 25 percent of residents are white.”

- “White and Asian borrowers, in contrast, were not only far less exposed to high-cost loans overall, they also exhibited far less variation across both periods and neighborhood types. In fact, the period effects that were so striking for black and Latino applicants are virtually absent in all but the most concentrated minority neighborhoods. And even in communities that are fewer than 25 percent white, the disparities with whites in predominantly white communities are modest; in 2005, the odds of a high-cost loan relative to conventional origination for whites in these neighborhoods were 1.4 times higher than among whites in predominantly white communities, compared to 3.8 times higher for black applicants in similar communities that year.”

- “The trends for rejection due to other reasons, presented in Figure 6, resemble those of bad credit rejections. Blacks are the most likely of the groups considered to be rejected due to unspecified reasons. The odd ratios for Latinos lie between black and white borrowers, while Asians more closely resemble white borrowers.”

- “Finally, as was the case with bad credit rejections, black and Latino applicants’ elevated rates of “other” rejection relative to whites is largest in predominantly minority neighborhoods. For example, in 2006 blacks (Latinos) in predominantly minority communities were 5.9 (3.3) times more likely than whites in predominantly white communities to be rejected due to other reasons (relative to being accepted into a conventional mortgage). Blacks and Latinos in predominantly white communities were “only” 4.3 and 2.7 times more likely than whites in similar neighborhoods to be rejected for unspecified reasons.”

Shane Phillips 0:06

Hey everyone, this is UCLA Housing Voice podcast back for episode two. I'm Shane Phillips and I run the Housing Initiative for the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies. And this podcast is all about making important housing research accessible to more people and trying to make sense of it in conversation with the researchers themselves. My co-host, as always, is Dr. Mike Lens. Mike, can you list off some of your many, many titles for us?

Michael Lens 0:32

Hi, Shane. I am associate professor of urban planning and public policy and the associate faculty director at the Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

That's right. Let's get started.

Shane Phillips 0:53

Today, Mike and I are joined by a new member of UCLA faculty, Professor Jose Loya. Dr. Loya comes to us by way of the University of Pennsylvania where he got his PhD. And he also worked on community development and affordable housing in South Florida for several years. Thanks for joining us, Jose, and welcome to UCLA.

Jose Loya 1:10

Thanks, Shane and Mike, I'm really excited to be here.

Shane Phillips 1:13

And since you're new to the school, and even we don't know a whole lot about you yet. Can you tell us a little bit about your background and your research interests?

Jose Loya 1:22

Yeah, definitely. So I actually was born and raised in Los Angeles. So I'm not actually completely new.

Shane Phillips 1:28

Okay.

Jose Loya 1:29

But I did leave for college and kind of never came back. So I'm new to the city as an adult, is what I like to say.

Shane Phillips 1:37

Um hmm.

Jose Loya 1:37

But I was born and raised actually in Northeast LA, in a small neighborhood called Glasell & Cypress Park, and then went off to college at Brown, and have just really been interested in housing probably since like the end of my, I guess, (the) end of my undergraduate experience at Brown. And so that kind of like, the mentorship and just experience in the classroom really just allowed me to get hands on with some of the housing issues that were affecting minorities in Providence, Rhode Island at the time.

Michael Lens 2:06

Hmm.

Shane Phillips 2:06

Did you have any sense when you still lived in LA before moving away of like, the changes that were happening? And I live in Lincoln Heights now and I see the changes, I'm part of the changes happening here. And so you know, you were just a few miles north.

Jose Loya 2:19

Yeah, that's awesome. I was always in Lincoln Heights though, I still go to...the Alote there, and the Palotero there.

Shane Phillips 2:27

Still here.

Jose Loya 2:29

And so yeah, I think growing up, it was a predominantly Latino community, very working class focused, I don't think the changes really started to occur until I probably was in my early 20s. And so growing up, I didn't really see those changes, because the neighborhood is still predominantly single family home, or single family homeownership. So the turnover just wasn't very quickly. But now as an adult, and just having returned, you definitely see a new presence, a new change in the culture, a new... just change in how people... I always joke with my mom, like, "there's bikers, now."

We didn't have bikers, but there's a bike lane. Those types of things that we just didn't have when I was growing up. And so it's kind of cool to see some of these changes, while on the other side also taking into account that there's also been some displacement of some previous residents in the neighborhood.

Shane Phillips 3:26

Yeah, well, welcome back. And the paper we're talking about today is titled 'The Great Recession and Ethno-Racial Disparities in Access to Mortgage Credit' and your co-author on this is Dr. Chenoa Flippen. I think I messed up that name, even though I asked you immediately beforehand how to pronounce it. So my apologies. So (who) you worked as a doctoral student at Penn. In this paper, you looked at mortgage outcomes for different ethnic and racial groups before, during, and after the Great recession. And those outcomes were either approval under a few different conditions or denial for a few possible reasons. And before we get into those details, and the results of your study, can you first give us some context for why this is of interest? I know, we could probably take this all the way back to redlining, racial covenants, or even further than that, but maybe we can just start with some stats on homeownership rates for different groups, and some history on how different ethnic and racial groups were treated in the mortgage market leading up to the Great Recession.

Jose Loya 4:33

Yeah, when we think about housing, I like to think of it as like the simple fact is that homeownership is the largest vehicle for creating wealth in the US. And so it's an important part and pillar of financial security for most families in the US. So whether we're trying to achieve homeownership, or those that are already in homeownership, this is like a huge... a key to some of the inequalities and wealth accumulation that we see in the US. And so this paper, in particular kind of examines the access to mortgage credit before, during and after the Great Recession. In many ways, I'm almost kind of looking over this paper, or we both, Chenoa and I, want to take, we know that market conditions aren't static over time. And so we wanted to explore whether or not inequality also isn't static over time.

Shane Phillips 5:30

Um Hmm.

Jose Loya 5:30

And so if we look at homeownership rates, for example, they've actually kind of remained steady since like the early, or since the mid 2000s, right? So when we look at whites homeownership rate is about 70% to 75%. When we look at black and latino, homeownership rates, they hover around 20%. So there's a 20% gap. Oh, and when we look at Asians, it's about 61%. So they were like in the middle, and we see that they kind of have been stable over time. And a lot of times we think of it as like, "what does that mean, inequality has just remained the same over time?". You know, different conditions in the housing market kind of lead us to think that just because we look at homeownership rates, but this paper is actually saying, like, let's look beyond just the rates of homeownership and examine how we access mortgage credit. How has that changed over time? What can that tell us about homeownership overall. And so it's kind of cool. There's some new papers coming out, that just kind of show that homeownership rate, the difference in homeownership rates, that 20 point gap has been there for almost 25 to 30 years.

Shane Phillips 6:34

Oh.

Jose Loya 6:34

And so that has huge implications when we think about social stratification, and ethno-racial inequality in the US more broadly.

Shane Phillips 6:42

Right. There's not, that catch up isn't happening.

Jose Loya 6:45

Exactly.

Shane Phillips 6:46

Mike, do you...

Michael Lens 6:48

Oh, yeah. Just a point of clarification. I think he said that the black and hispanic homeownership rate was around 20% the first time, but if the gap is about 20% to 25%, depending on the year, whatever, while I'm here, you know, specifically, what came up your interests about... as far as coming out of the Great Recession, right? Because like, so much has been studied, leading up to the Great Recession, and what're some of the impacts on... what are some of the borrower outcomes were, what some of the foreclosure outcomes were, losses in wealth, etc. What was your interest in looking at these gaps in terms of loan outcomes coming out of the Great Recession?

Jose Loya 7:33

Well, the first is, we know very limited information on what's happening after, so we kind of, at least when we examined the literature, we see that there's like you said, huge emphasis during the housing bubble, predominantly in like the arena of like subprime mortgages in terms of access to credit. During the crisis, we see that simply, there's no access to credit for anyone. And so because of that, we see that the stall, the housing market really just stalls out and declines significantly. And to a certain extent, we see that the recovery period, and one could argue that we're still recovering, that it's been pretty solid, yet, we don't know how minorities in particular, are participating in mortgage credit or in homeownership access. So I think there's a limited understanding. And the third thing, and really important is, what kinds of loans are people getting now, right? So we have this huge understanding that people in the bubble, and during mostly the bubble, were getting high cost loans, or just proportionally getting high cost loans if you're a minority. Well, now that we've regulated to Dodd-Frank, and lenders are much more "cautious", when it comes to high cost loans, what does that look like now, for minorities that once utilize them at a disproportionate level? What does that look like now as the market is increasing and recovering, and in a lot of ways, creating wealth for homeowners again? So that was that third interest, which is what kinds of loans are people actually taking up? And to a certain extent, are we going to do what we've been doing? In other words, do we have another bubble coming?

Shane Phillips 9:07

Right. I do feel like that's part of what this is getting at is, have we learned any lessons? Did we make any changes so that we're not going to repeat the same mistakes?

Jose Loya 9:17

Yeah.

Shane Phillips 9:17

And so I think we're going to answer that in a few moments. For this study you're, as we said, you're expanding what we know from before and during the Great Recession, and comparing that to the post-recession period, up through 2017. For this paper, and to set the stage here, you have mortgage applicants who can be approved with either a conventional loan, so kind of normal standard interest rates or a high cost loan, which is, you know, a couple points above. So like, if a standard loan is 4%, they might be getting like a 6% interest mortgage or something like that. And those high cost loans are sort of, I don't think they're exactly the same thing, but they're sort of analogous to the subprime loans that we're kind of more familiar with. And then alternatively, if they're rejected, they could be rejected due to bad credit, or they could be rejected for a "other reason". So you looked at these data for Black, White, Asian and Latino applicants for every year from 2004 to 2017. What did you find?

Jose Loya 10:21

So we found three interesting things. The first one, which I guess I was alluding to, in the beginning, was that in fact, ethno-racial inequality is heavily tied to market conditions. And what I mean by that is, when times are good, we see large inequality or large ethno-racial inequality in the mortgage market. When times were bad, like the Great Recession, we see this inequality shrink dramatically, especially for Asians, to whites, and however, it does shrink dramatically for Latinos, and blacks as well.

Shane Phillips 10:54

So it's... I mean, are you saying basically, like, when times are bad, they're bad for everyone, but when times are good, they're better for white people and asian people, and not so much better for black and latino people, essentially?

Jose Loya 11:08

To a certain extent, yeah, I'm saying, almost, I mean, if we have an example, I have the ability to discriminate more, because I have so many more options to lend, you know, to different buyers. So I can choose, pick and choose who I want to lend to. And then during the recovery period, which was really interesting to me, was that we start to see inequality begin to expand. And so we see it up through 2017. And in the paper, we document these differences across ethno-racial groups. And so that was the first one. The second one was that the borrowers looking to... the types of borrowers in the mortgage market also changed dramatically. So we see that more specifically, a huge drop off in Latino and Black borrowers, in the number of Latino and Black borrowers during the Great Recession. And so we see that across the board for everyone. However, it's especially true, more dramatic for Latinos and blacks. But during the recovery period, Latino and Black borrowers just don't come back. So we see a sharp rise in the number of White and Asian borrowers, but we don't see that dramatic increase for Black and Latino borrowers. And so that's the second one, which is we see, really a demographic change in the types of borrowers in the mortgage market. And then the third one, which is the thing I think a lot of people like to talk about is that the odds ratios, or the disparities during the recovery period, begin to reflect the disparities that we see during the housing bubble, which is especially alarming when we think about the types of regulations or the tightening of regulations in the mortgage market through Dodd-Frank. And so even with that kind of legislation, we begin to see this increase in high cost lending or the odds of getting a high cost loan, again, for black and brown borrowers, which is something that we don't typically talk about or expect in the current economic situation.

Shane Phillips 13:10

And so I want to make sure I'm fully understanding, you talked about during the recovery, more white and asian borrowers kind came into the market. And they started to kind of filling in the drop that occurred during the Great Recession, and shortly afterward, but Black and Latino borrowers did not really come back. And yet, over time, the share of Black and Latino borrowers who have been getting either rejected or getting approved for high cost loans has been growing. Is that right?

Jose Loya 13:42

Yeah, exactly. And so...

Shane Phillips 13:44

It's not like, you know, more people are flooding into this market. And lenders are saying, "Well, you know, you were a marginal person who just now is coming in, and then we're going to reject you.". This is, you know, we can't be sure, but it's the same number, if not exactly the same people.

Jose Loya 14:00

Well, the odds, yeah. So...

Shane Phillips 14:02

Yeah.

Jose Loya 14:02

... it would be. I mean, if we look at just mortgage access, in general, we see a huge drop off in high cost loans. And in fact, when the HUD data set, which is where this data comes from, when HUD reports the HUD data set, they show that subprime lending, or high cost lending, I should say, remains really low. And that's true, but that's because disproportionate number of borrowers are actually White, compared to what we had in the past, when we had great... When Black and Latino borrowers had greater access to this credit. However, the odds of getting a high cost loan if you're black or brown, during the recovery period, is still the same as what we saw during the bubble. And so that is particularly like, problematic when we think about this shift in the demographics. So we also see not just talking about like an ethno-racial shift in the demographics, but we also see that incomes have risen, right? So we have, technically we can argue that we have more qualified buyers in the market, yet they're still just as likely to get these problematic loans when we control for loans.

Shane Phillips 15:08

Right.

Jose Loya 15:08

And that's pretty alarming. To say the least.

Michael Lens 15:12

And Jose, did you say that coming out of the Great Recession, that gap between white borrowers and hispanic and black borrowers has gotten larger in terms of the likelihood of which that they're going to receive high cost loans or be rejected?

Jose Loya 15:33

No. So actually, that difference during the Great Recession fell dramatically. And so during the housing boom, if I'm not mistaken, we're talking like black and latino borrowers were more than 200% more likely to get a high cost loan that fell to like less than 50%, during the Great Recession. But then we begin to see that....

Michael Lens 15:55

Right. So specifically, I am asking about like the 2012 to 2017 period, does that gap widen over time? Or does that happen kind of right away, coming out of the recession?

Jose Loya 16:09

So it does take a couple years. So if we look at some of the figures, you'll see that actually by 2013, and 2014, we're approaching 2004 levels, 2005 levels, but it does take three to four years to get to that point. So we do begin to see like a slight, you know, almost like a linear increase in the odds of getting a high cost loan.

Michael Lens 16:32

Got it.

Jose Loya 16:33

And I would say that, that increase is only magnified or is very dependent on the type of neighborhood that people are applying to. So we see that, that increase is more dramatic in predominantly non-white neighborhoods.

Michael Lens 16:48

Yeah. So that's what I want... That's another thing I wanted to follow up on, of course, is like the neighborhood story, because some people well, there's a couple things going on with why there might be racial disparities here and the, you know, Achilles' heel of the home mortgage Disclosure Act, or HMDA data is that you don't have credit scores, right? You don't know exactly like everything about the borrowers. And so you can't make perfect apples to apples comparisons. So some might say, Oh, well, you know, lenders are making judgments based on credit worthiness. And then another person might also say, and because of racial segregation in this country, there might be riskier investments in predominantly minority neighborhoods. And again, lenders are making good judgments based on like, not really wanting to lend in those areas. And of course, we've got legislation that has dealt with that over the years. But like, how do you think about kind of those two issues with, you know, the lender perspective?

Jose Loya 18:04

Yeah, no, that's a great question. So I think there's two ways. I'll attack the neighborhood one first, I think it's a little easier, which is in the paper, we also want to control for these economic factors in the neighborhood. So in addition to the borrower characteristics, like loan, income and loan amounts, we also took a look at like local labor market, so unemployment in the area, we looked at the income in the actual neighborhood or census tract, of which they were trying to buy the home, in addition to just examining the ethno-racial makeup of that neighborhood. And so that's kind of how we tried to look at some of that. We also took into account, so Massey and Roo have access to credit scores in an area. And so it's like more of a contextual variable, it's not really going to do much. I mean, just because the country is so large, and you're just getting an average effect. However, I would say that when it comes to the lack of credit score, I agree, the data set doesn't have credit score. However, one of the interesting parts about this paper is that we disentangle the outcome. And one of the outcomes is a denial due to bad credit. And that's especially important because theoretically, with that variable, I can say, "Well, I'm controlling for credit, these are all people that have technically have bad credit.". So everyone in this sample, or at least in this outcome, has had, like the bank has provided a reason for a higher... that this individual has higher risk. And so by doing that, or having that category on its own, we should see, essentially noise in a lot of ways, right? We shouldn't see any variation, we shouldn't see the same type of pattern that we would see in high cost loans are denials due to other reasons, but in fact, it's the same pattern, right? So even if we think about like, "Well, what about the credit, maybe the credit would mitigate this entire pattern.". Well, this one outcome, which the banks themselves have to provide a reason for when an individual gets denied. These are all people that are "higher risk", or economically higher risk. And yet, that same pattern that we see with Black and Latino borrowers is maintained

Michael Lens 20:15

Right.

Jose Loya 20:16

And so I think when I was presenting this paper at conferences, that was the big one, I remember a couple bankers and an economist came up to me and was like, "that's why your paper makes sense.". Not for this other stuff, but because I was able to technically control to a certain extent some of these, some of the applicants by saying, well, actually all of them have bad credit. So there shouldn't be any ethno-racial... the disparities should almost, there should be noise, right? We shouldn't see a pattern. And yet, that pattern still maintained. And so I think that was what, you know, pushed this paper along.

Shane Phillips 20:50

And that's a good lead into. So one reason for rejection was bad credit. That's very explicit. The other reason is just other reasons. And so it can, it can mean a lot of different things. And those other reasons, rejections were much higher for Black and Latino applicants than for White or Asian applicants, you could say, you know, the other reason is just outright discrimination. But it's hard to know, give the catch-all nature of that term. So are lenders required to provide any other information beyond checking as other reasons box or like, how do you interpret that outcome for people and particularly the disparity in that outcome?

Jose Loya 21:36

Yeah, that's a really excellent question. So as part of HMDA, in addition to just the application outcome, if an individual's denied each institution has to provide a reason for that denial. And there are nine different reasons, eight of which I call bad credit. So for instance, an individual can be denied because their employment history, if they have an incomplete employment history, their debt to income ratio is really high, they don't have enough down payment or collateral, their credit scores is poor, they don't have enough... their income doesn't meet the threshold. There's various economic reasons, right?. So that's why I call it bad credit. However, there is this one reason. So the banks or the financial institutions do have to provide a reason to the borrower as to why they were denied. And this one reason that it has nothing to do with, I would like to argue, is not economically driven, is you could be denied simply for other reasons. It's unclear what those other reasons are. But...

Shane Phillips 22:37

Right.

Jose Loya 22:37

... we know that it's probably not related to economic reasons, because had it been an economic reason, they would have checked off one of the other eight boxes.

Shane Phillips 22:45

Yeah, they have plenty of other cases for that.

Jose Loya 22:47

And so for the most part, that's how we separated that one out. Because it was enough... there was enough individuals, or the proportion of people that were being rejected, were enough to actually consider it its own category. So it wasn't just like a random lesson, half a percentage point or a few thousand people when we're talking about millions of observations, this was a significant component for a lot of Black and Latino borrowers. So they were simply being denied due to other reasons. And in fact, I actually saw a letter once it was like, "you've been denied and the reason is unspecified.". And so they do have to provide this reason, but it's unclear what that reason actually is. That's why we put it in quotes. It's literally... when they have to submit this to the federal government. It's other.

Shane Phillips 23:38

Yeah, that's frustrating, because what do you do with that? And how else do you interpret it, especially given those despariies?

Jose Loya 23:44

Yeah well, the interesting part. So that was, you know, that the paper only goes up until 2017. The last 18 and 19 have actually recently been published. And there were some cool additions to that. So going back to Mike's point earlier, they added debt to income ratios, property values, they added some additional economic like variables. And guess what we see now, we see a dramatic decrease in the number of denials due to other reasons. I mean, I haven't run a model. I don't know why I just find it to be an interesting coincidence that when they're now requested to provide additional variables, that this denial, for other reasons, is literally now less than 1%. And so this is more like in line with what I thought I would get. But in previous years, we saw this like larger, there was a larger proportion that were being denied due to other reasons. I can't tell you why I don't work at the bank.

Shane Phillips 24:40

Yeah, I mean, I feel like I'm hearing you feel like there's some nefariousness here, but it does kind of sound like maybe the lenders were like, hey, you have these eight options that are all economic and then we just are left with this other reasons. We got these other things that we think would also make good ones too. checkoff. So were those reasons for denial are those are just data points that are separate, just to be...

Jose Loya 25:06

Yeah, those are actually just separate data points, not even for denial. And actually, the data points are just actually, some of the reasons that people were denied before, right? So like high debt to income ratio, you still can be denied due to high debt to income ratio. But now I also have what that percentage is. So now I know it's like 50%. So maybe that one financial institution views 50% as too high, or something like that. So now we can actually compare some of this variation that we couldn't see before, we just have to say, Oh, it was high debt to income ratio, we don't actually know what that means. Now, you can do a little more like in depth analysis. But I did find it interesting that the moment that HMDA requires a little more information, this one category, all of a sudden, it's kind of like no longer as applicable for...

Shane Phillips 25:54

Yeah, sounds like a good story. That's progress. I think my next one is a big encompassing question. And it is, what is causing this? And maybe, you know, based on your answer, what do you think we could actually do to fix some of these things? I have a few notes down here of like possible things I put down? You know, is it an issue of lending based on neighborhoods rather than people? Is this something with like financial FinTech, you know, big data, where you have inputs that are perpetuating past discriminatory treatment? Is it just plain old racial or ethnic discrimination? What's going on? And then what do we do about it?

Jose Loya 26:41

Yeah. So I would be remiss, like it's very difficult to prove discrimination in any dimension, especially in housing, right? So I don't have the luxury of being able to do audit studies, in this case, and it's very difficult to do an audit study with the financial institution to see whether or not someone would qualify or not qualify.

Shane Phillips 27:00

Maybe you can tell a little bit about what previous audit studies have found, just for some context that people kind of understand what the typical finding is for those and what they are.

Jose Loya 27:10

So HUD actually has invested in a couple audit studies over time, the first one that they did was in the late 80s, where they kind of tracked Black and Latino borrowers, White, Black and Latino borrowers through the home buying process, essentially gave them very similar characteristics, and did these Kwazii, and did these experiments in different cities across the country. And what they found was that discrimination, and they did this in the late 80s, early 2000s. And I think they tried to do one in the late like, 2009, 2010. But for the most part, like the big ones, where they found that discrimination overall in housing has gone down. However, it still exists. And so what they found is, you know, I think a lot of people were cheering because they're like, "wow, look, it's gone down dramatically.". And it's like, yes, but it's still really high. And it's still a major barrier for minority homeowners.

Shane Phillips 28:04

And that's not just, you know, discrimination with lending. It's also realtors not showing black families homes in certain neighborhoods, and many other...

Jose Loya 28:13

Correct, so that's steering, that's the quality of the service that they received. That's also the type of loan products that they were offered. Also the fees that people, that the individuals have to pay when they're looking to buy a home. And so across the board, Black and Latino borrowers or Latino homeowners they had higher prices and more barriers to overcome to get to homeownership. And so while it's declined, it's still massively prevalent in the housing market. And that's what HUDs point of the study was. Now, in terms of like how the mortgage industry has evolved over time, which goes to your second point, or your second thought, which is a lot of this is being driven by like big data. So when we talk to our parents, or when I talk to my mom or my grandmother, a lot of them had relationships at the bank when they were growing up. So when they got a loan-loan, they went to their local bank, and they asked for a loan. And they assumed that they were getting the loan, the best loan product that the bank could offer, that there wasn't going to be a lot of shopping around, because you had that one on one relationship. That's changed a lot, right? So now we can get approved for a loan, you know, with our computers. I don't technically have to see a mortgage expert, or meet with a banker until closing potentially, right? A lot of it is actually done over the phone. And so for a lot of the major financial institutions, if you were even interested in buying a home, they're just gonna put you on a phone at the bank, because they don't have a mortgage broker there. And so how banks now do it is primarily through big data, right? So we have these and so when you ask me like, what do I believe the mechanisms are? This paper doesn't prove or can't... doesn't really show what the true mechanisms are, as much as it's just documented the demographic changes and transitions of inequality. But I would argue like if I was to read beyond my paper and and just in the literature in general, that, at least in the mortgage market, we are replicating the type of society through our big data analysis that financial institutions are using. And so that's...

Yeah.

... you know, big data is only as good as the data that you have. And if the data that we have is all messed up, you buy it and unequal to black and brown communities and borrowers, then that's what we're going to replicate.

Michael Lens 30:26

Yeah.

Jose Loya 30:26

And so I think that's what we see right now. That's what we're seeing, especially as neighborhoods transition.

Michael Lens 30:33

Yeah.

Jose Loya 30:33

And so that's kind of like, it kind of sucks to say, like, "Do I know what the mechanisms?". I wish I do? I have an idea, but...

Michael Lens 30:42

Yeah, I mean, on the like, big data algorithm front, you know, I'm far from an expert on this at all. But it sounds, to me, like the evidence is pretty strong that the algorithm is not a sentient being and can't see race, but the algorithm is racist. That's bad news. Um, you know, shout out to Safiya nNble at UCLA for her book, 'Algorithms of Oppression', which I haven't read, but I know, it tells us the algorithms racist.

Jose Loya 31:16

Yeah, I think I mean, it's difficult, right? Like, even when we read, so I am interested in like, big data. And when I read the computer science papers that talk about it, you almost see them like, it's like the wild wild west in lot of ways, they're pushing the limits to what computer analysis and document... like what it actually means, right? And so it's interesting to see that the type of data that they're using is the data that we as social scientists use. And so if we see that this inequality is occurring, in a lot of ways the computer doesn't know, the computer has no... like, it doesn't know theory, it doesn't know how our society is, we just feeding it the data that we believe essentially reflects the society that we're in. And so if our society is highly unequal, then you're going to get these unequal results, like you said, I don't need to know the rates of a borrower if I know the type of neighborhood or that you're trying to buy a home in. And that'll give me an idea as to price appreciation over time. And turnover in the neighborhood and the average housing stock and whether or not there's new permits coming in like that information is pretty readily available, just with knowing the census tract. And that's pretty scary. But I also think that should be the point of emphasis for public, like for public policy is like, "well, we do know, we know where segregated neighborhoods are, we know where there's a void in lending, and how do we kind of reverse some of those patterns?".

Shane Phillips 32:41

Yeah, and I know that this is sort of, we're getting beyond the scope of your paper itself. But you know, we want to talk about the solutions as well. We know that there has been progress made, as you said, discrimination is not as bad in the housing market as it used to be prior to the Fair Housing Act. And presumably, it's improved fairly incrementally. But you know, what else can we do? Because it's clear that the Fair Housing Act, the anti-discrimination provisions, the audit studies are not doing enough. They're very reactive, I guess. So like, have you read anything about what we can do to be a little more proactive about this?

Jose Loya 33:19

Um, I think, as a researcher, and as a scholar, there's always well, I need more data, right so first point

Shane Phillips 33:27

I think everyone we've talked to has said that so far.

Jose Loya 33:31

Shocking! But I do think that like our communities, if we're talking like, it depends on the type of problem that we're trying to solve, right? And so is it housing? Or we talking like, when we talk about housing, is it because we're talking about wealth inequality in the US? Is it because we're talking about quality of life in the US? You know, like, what type of inequality are we trying to address? And I think that'll kind of guide the type of solution that we're looking for. In fact, I see myself more like day after day, and maybe this is because I'm just in front of my computer all day at home is like I always ask myself, like, "what about the other side, like the rental side? What does that transition look like? And how..." I find myself over and over, like describing all the incentives to homeownership. And yet, I almost am like lost, but what's the incentives for renting? And why isn't that something of emphasis when we think about public policy in terms of providing quality housing for families, or opportunities, right? And so if we're talking about like, the type of neighborhoods people live in, like one of the... I mean, we'll go back to like, Lincoln Heights has these beautiful, beautiful like Craftsman-style homes, right? Is it necessary that someone has to own it? Or is it just as important to have people rent it but have like the parks and have access to good quality schools like what is really the value of homeownership, rather than just... so I find myself thinking more about that at home. And maybe that's a bad thing.

Shane Phillips 35:02

I can say I'm right there with you more than you know, I have a 3000 word rental pension idea basically, that I've been writing in the evenings on the weekends that I'm going to probably run by all you guys pretty soon. I don't think it's a Lewis center thing really, it's a little too off the wall but I've been thinking about exactly...

Jose Loya 35:23

But I do think that like the important part is like the incentive part. And I think since you know, really since the creation of FHA in the 1920s, homeownership has been highly subsidized, highly incentivized. And then I think to a certain extent, even me, as a scholar, I lose focus as to like, well, what's the other side? Can we create incentives for renting? Is there an opportunity for renters to also increase, you know, social mobility, or decrease the wealth gap that we currently see? So I'm concerned with the wealth gap. And so that's where I would probably focus my attention.

Michael Lens 36:00

Yeah. I mean, you know, since, you know, it's hard for me to shut up right now, because I'm somebody who studies the rental side, far more than I studied the homeownership side, right? And to me, like, one thing that makes your paper so important and interesting is like, I bristle at this idea that homeownership has to be widespread in order to create wealth, right? Because I don't think a home should be such a source of wealth for people or should take up so much of their total wealth pie, right? Like, I think a lot of bad things come from that. And, you know, we'll talk about some of those things on like, seven other podcasts, but like, you know, to me, what's really like, makes me you know, gnash my teeth when I read this paper is I think about why we think of homeownership is such a wealth builder, is because it used to be an incredible wealth builder in the United States, largely for white people, because we essentially banned non-white people and mostly black people in cities, across the country, from owning homes, just when it was a perfect time to buy a cheap house that in 20 years later is gonna be five times as expensive, right? And so that, but I think that you're studying a different but similar time period, right? We're like, coming out of the Great Recession, there were a lot of great deals, you know, we saw this housing market collapse in so many places, and I was one person in 2012, who bought a house. And this house is now a lot more expensive than it was then, and I got lucky. But like, if the mortgage market was like, "let's get back to our discriminating ways", that's really really bad. Because this is again a pretty good... this was a good time period over the last eight years or so, to build that wealth. And that just feels really, makes me mad, pretty mad.

Shane Phillips 38:11

And I think we're kind of, our minds are warped a little bit living in California, where we kind of assume it's just like normal that all property appreciates in value at this rapid pace. But like, you know, if you bought a home in Cleveland, 30 or 40 years ago, again, you're worse off than if you had not bought at all. And so yeah, I 100% agree with all that.

Michael Lens 38:35

Yeah.

Shane Phillips 38:35

I know, we got to wrap up here pretty quickly. But I tried to ask this of all the researchers we bring on. With this paper, were there any questions that you weren't able to resolve something that you're kind of looking to address in the future without giving too much away and allow people to scoop you...

Jose Loya 38:53

Well, I mean they can try. So I would actually like it. I am interested to see... so one of the things that we did was just the neighborhood racial composition and the composition of the borrower. But I'm actually also really interested in kind of like, what Mike's point, and what we kind of brought up in the last few minutes, which is, what happened, like, what's the impact of the credit market on low-income Blacks and Latinos versus high-income Blacks and Latinos through these different stages? And did access look differently for all of them, when we think about Whites, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians? And so I think the next...

Shane Phillips 39:26

Yeah

Jose Loya 39:27

.... essentially, that's the paper, right? And so the next one is to look at, well, what does that look like in terms of different socio-economic classes, in terms of their access to mortgage credit? And does that tell us more? Maybe this idea of wealth, like that we sell people or this idea of homeownership that we sell low-income individuals or low-income families, maybe it's a farce, maybe there's not... maybe there are no low-income families that are actually trying to purchase a home. And so we were selling this idea that they have limited access to and so that's my next interest.

Shane Phillips 39:59

I remember pulling out some data years ago, just looking at different cities their median value and how much it had grown over, you know, 20 or 30 year period. And the places that were most expensive in 1980, or 1990, they actually grew in percentage terms at a higher rate in value than the home values in these cheaper areas. So if you could afford a home in Los Angeles, or New York, or Seattle, in 1990, then it was a great investment. If you couldn't afford a home there and you bought, you know, in the Rust Belt, or somewhere in the Sun Belt or something. The appreciation just wasn't as great. And so you know, the people who could afford the most got the best returns and the people who couldn't either appreciated very slowly, or maybe even lost value. And so it's, you know, this rich get richer kind of situation.

Jose Loya 40:48

Yeah, exactly. I kind of want to see, and I want to see, maybe there's differences amongst different ethno-racial groups, and especially because they're also regionally spatially, we're pretty... different ethno-racial groups are just spatially concentrated to specific areas of the country. So I want to examine that kind of like, what that social structure looks like. Just makes sense.

Shane Phillips 41:06

Yeah. All right. Well, I think we're all done here. So thank you so much for joining us.

Michael Lens 41:11

Thanks Jose.

Jose Loya 41:13

Thanks, Mike and Shane, have a great day.

Shane Phillips 41:22

That is a wrap on today's episode of the UCLA Housing Voice podcast. We have links to Jose's work and the other articles mentioned during our conversation in the shownotes, including my zany rental pension idea, which was recently published in The Atlantic. You can keep up with us on Facebook and Twitter @UCLALewisCenter. And you can follow me @ShaneDPhillips and Dr. Lens @MC_Lens. help other people find the podcast by rating and reviewing the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, wherever you like. And we will talk to you soon. Thanks

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

About the Guest Speaker(s)