Episode 01: Evil Developers with Paavo Monkkonen

Episode Summary: Which arguments against new housing are most effective? Residents were asked how they felt about a hypothetical housing development proposed nearby, then told about the concerns of some of their neighbors: traffic congestion, neighborhood character, strained services, or developer profit. Surprisingly, the developer profit argument was the most effective at reducing support for new housing, although opposition declined when residents were informed that the developers also provided community benefits with their projects. Paavo Monkkonen of UCLA joins us to discuss these and other findings from his research. Show recorded October 2020.

- Monkkonen, P., & Manville, M. (2019). Opposition to development or opposition to developers? Experimental evidence on attitudes toward new housing. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(8), 1123-1141.

- Hankinson, M. (2018). When do renters behave like homeowners? High rent, price anxiety, and NIMBYism. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 473-493.

- Piecing it Together: A Framing Playbook for Affordable Housing Advocates. Enterprise Community Partners.

- Whittemore, A. H., & BenDor, T. K. (2019). Exploring the acceptability of densification: How positive framing and source credibility can change attitudes. Urban Affairs Review, 55(5), 1339-1369.

- Paavo’s CV!

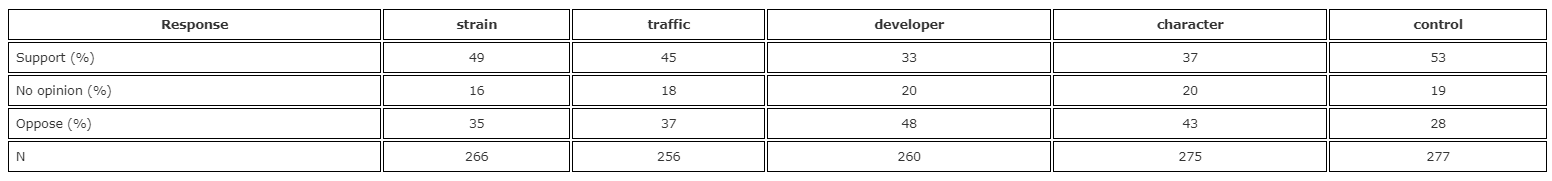

- “Our results suggest that anti-developer animus is a powerful source of opposition to housing development. Survey respondents “treated” with a narrative about developers earning large profits from a hypothetical housing development were 20 percentage points more likely to oppose that project than were respondents in a control group. They were also more hostile than respondents treated with other anti-development arguments, which focused on neighborhood character, congestion, or strained services (these latter frames were 15, 10, 10 percentage points more likely than to oppose the development than were control groups).”

- “When residents oppose new housing because they believe it will congest their streets, they are acting in their own self-interest: working to prevent their own loss. When residents oppose new development because a developer might earn a large profit, however, they are working to stop someone else’s gain. This action suggests a separate dimension of NIMBYism, centered less on risk aversion and more on enforcing community norms of fairness.”

- Survey question for control group in predominantly single-family neighborhoods: “Suppose a developer proposes to build a three-story apartment building on your block. The proposed building, which will contain 20 one-bedroom and studio units, is designed by Camarillo Architects, who have developed multi-family residential projects across Southern California for decades. Early renderings show a building with tasteful contemporary architecture and ecologically sensitive landscaping. Some advantages of this development are clear. Los Angeles badly needs more housing, and city planners hope that new construction will help make rents more affordable.”

- For respondents in predominantly multifamily neighborhoods the building size is increased to 10 stories and 90 units, but otherwise basically the same.

- Respondents in the treatment group were given some additional messaging about opposition to the project.

- For example, one relates to cars and traffic. It says, “However, some of your neighbors oppose this project. They worry that it will lead to increased traffic in the neighborhood and make street parking harder to find. Traffic and parking are always sources of concern to Angelenos, and there is reason to think that new housing does mean more cars.”

- There are three other opposing messages, one focused on neighborhood character, another about strain on local services like parks and schools, and the last one is about developers.

- The developer one reads: “However, some of your neighbors oppose this project. They point out that the project’s developers obtained a special permit from the city, which lets them build at a higher density than zoning would normally allow. The developers stand to make large profits as a result. Your neighbors argue that the City Planning Department should not be in the business of making developers rich.”

- “Of the respondents who opposed the development in their own neighborhood, 21% had no opinion on the building when it was proposed in another neighborhood. We consider this weak NIMBYism—opposition to housing nearby but indifference to it elsewhere. Another 23% actually supported the proposal, which we consider strong NIMBYism—opposition to housing nearby but support for it elsewhere.”

- In other words, about 45% of the people who opposed the project in their neighborhood changed their position when it was proposed elsewhere. Assuming these numbers apply to the control group, that would mean that putting the project somewhere else increased support from 53% to about 59%, and decreased opposition from about 28% to 22%.

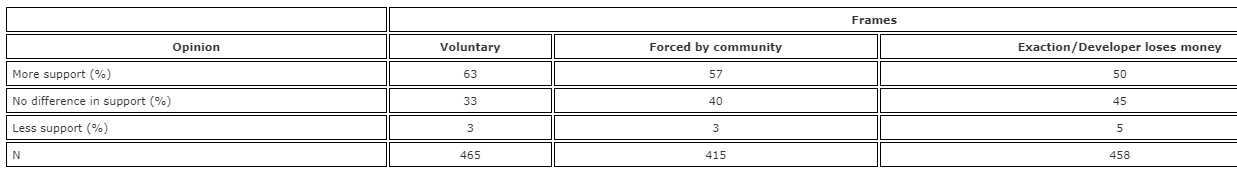

- Table 4 shows results from the second experiment, which examines the role that mitigation might play in changing people’s minds about a development. In this experiment, we test not the benefits themselves but the manner in which they arrived: if the developer volunteered them, the community forced them, or the city exacted them as a matter of course (at great expense). In this experiment, we did not use a control frame.

- “Strictly speaking, in high-demand, supply-constrained cities, new development is itself a form of mitigation. It delivers needed housing, and helps make housing more affordable. But if residents find the manner that housing is produced distasteful, then a community norm of fairness might block an equitable policy. This scenario is not outlandish. A hallmark of expensive markets is that developers often do need to lobby and negotiate for permission to build, which in turn makes most development feasible only for deep-pocketed developers who are able to lobby, and to carry land costs while they do so. If people oppose development in part because they see developers as rich, confrontational, and willing to bend rules, they could trigger a self-fulfilling process. Communities suspicious of development will clamp down on it, and by clamping down they increase the probability that developers will be rich and confrontational.”

Shane Phillips 0:06

Hello, and welcome to the UCLA Housing Voice podcast. I'm Shane Phillips and I run the Housing Initiative for the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies. And I'm joined by my co-host, Dr. Mike Lens, associate faculty director for the Lewis Center. This podcast is about making housing research accessible to everyone. And we do that by talking to the researchers themselves. We want to know not just what the latest research tells us about the problems we face, but what it says about how we address them. I think I speak for both of us when I say that research isn't everything, that knowledge alone won't solve all of our housing challenges, but it certainly helps. And there is so much to learn. A lot of this work is hidden behind journal paywalls and insular academic speak. So our goal is to bring this work to light and share it with all of you.

We're joined today by Paavo Monkkonen co-author with our colleague Mike Manville, on an article titled 'Opposition to Development or Opposition to Developers: Experimental Evidence on Attitudes Toward New Housing'. We're gonna start off with a little background Paavo. What brought you to the study of housing policy? I know, you're generally focused on housing production, approval processes, that kind of thing. So why housing and why that specific element of housing.

Paavo Monkkonen 1:43

Hey, Shane, how's it going? Thanks for having me on. It seems quite formal considering we talked recently, and we just got a research grant together...

Shane Phillips 1:51

Yeah.

Paavo Monkkonen 1:51

... to study affirmatively furthering fair housing, which is very exciting. Yes, it's a interesting pair of questions, I guess the origin story. I actually owe credit to Vinit Mukhija, our colleague at UCLA Urban Planning, I was his research assistant when I was a master's student in public policy. And we worked on informal housing and like a federal program in the US to improve rural communities in California. aSo that kind of sparked my interest originally in formality and informal housing. And actually, most of my work has been on housing in Mexico, especially around like the "social housing program". It's like a mortgage finance program run by the federal government.

And I have done a lot of research as well on public housing in Hong Kong. So it's funny that you asked the second half of this kind of "why do I spend so much time focusing on zoning reform?" Because I think probably if anyone has ever seen my work in Southern California, it would be the zoning reform stuff. But that's only one of the things I do. But I do think it's important. I think that, you know, as our project on FFH speaks to... and this other thing we've been talking about in terms of how to get affordable housing in single family neighborhoods through like a missing middle with a subsidized unit in the five plex, right? I think zoning reform is like an important piece to the increasing affordability generally, and increasing the number of affordable housing units kind of that exist. So you know, that's why it has become such a focus and the attention in you know, at the state level in California to actually doing something about it I think, is also one of the reasons that I've been working on it more lately.

And I should probably mention that we're joined by Mike lens as well. Mike, do you want to just introduce yourself here?

Michael Lens 3:40

Oh, sure. Shane. I'm Mike Lens. I'm an associate professor of Urban Planning and Public Policy at UCLA, like Paavo. And I am the associate faculty director of the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, which brings us this podcast, I had a follow-up question for Paavo. So you mentioned kind of your origin story in housing. But there's a lot of different ways that you can impact housing affordability or housing access. We have, you know, a large army around the world of people who advocate on the behalf of people who don't have affordable and safe housing. And we have researchers and we have everything in between, like, what made you think that research was the way to have...

Umm, good question.

... an impact in this world? And like, you know, how do you think, you know your research like ours can have that kind of impact?

Paavo Monkkonen 4:44

That's a very good question, Mike. And I want to hear your answer too but I think you know, so when I did my master's in Public Policy, my plan was definitely not to do research. My plan was to take action in the world and change things. But throughout that program and through my internship, I actually did an internship at the World Bank, just to see how evil it was. And I saw that research had a big impact on the way they did things and the way they structured policies. So that was kind of how I started understanding the importance of research and ideas and shaping policy outcomes. And also, I mean, just, you know, kind of selfishly, I really love doing research and the flexibility and independence it gives me in terms of setting out what I get to do with my time. So a little bit of recognizing its ability to impact the world and really enjoying it. What about you?

Yeah, I mean, that sounds more deliberate than what I remember.

Michael Lens 5:40

I was kind of naive, you know, also, you know, as a master's student, thinking like, hey, if we just, like found the right data, and we did the right study, we can find what works. And then the world would do what works.

And of course, like, you know, even though finding out what works part is incredibly hard, and, you know, in most major societies, taking the what works and translating it into political action is a very different thing.

Paavo Monkkonen 6:17

Indeed.

Michael Lens 6:18

So yeah, that was kind of what got me on that path.

Paavo Monkkonen 6:22

Yeah, I think it takes some of us a while to realize.

Shane Phillips 6:26

Meanwhile, I just never saw the appeal at all.

Paavo Monkkonen 6:29

But here you are.

Michael Lens 6:31

But we called you in still.

No PhD for me, anyway.

But you're at the university.

Shane Phillips 6:37

Yes, that's true. Let's talk about the paper a little bit. The study that you did, it was a survey, looking at how different messages about housing affected people's support or opposition to a development proposal in their neighborhood? And, you know, if I could summarize it in one sentence, I would say that the like, big finding for me is that people dislike developers even more than they dislike traffic, can you give us like a little more detail? We're gonna get into the real details here going forward, but just like a little more detailed summary than that.

Paavo Monkkonen 7:07

Sure. Yeah. No, and especially in LA County, that was a big surprise to us as well. Yeah. So I mean, the basic idea was just to see which kinds of arguments against housing project near you would make you more likely to oppose it.

And so we... kind of the innovation was we randomly assigned respondents to the survey into five different groups. One of them a control group, saw no argument against a hypothetical housing project on their block, the other four groups saw different kind of neighborhood concerns over what that project might do. And so we looked at kind of parking and traffic as one frame. Strain on the local public services, like the parks will be crowded kind of as another frame, ruin the neighborhood character as another frame. And then the developer will make a lot of money, because they got a variance as the fourth frame. Yeah. And so I mean, it was striking to us how much the developer profit frame motivated, more opposition to the hypothetical project. I mean, it was slightly more than the neighborhood character one. And both the neighborhood character and the developer framework were significantly more than the strain on parking, sorry, the strain on services in the parking frame.

Shane Phillips 8:25

One of the things I found interesting about this was, you know, usually, I think the issues we focus on when we talk about opposition to housing, are like the direct visible things that people will usually admit to, like concerns about traffic congestion, aesthetics, property values, stuff like that, or things they often won't admit to, like prejudice against different racial or ethnic groups or poor people. These are ultimately about impacts of the housing itself, or of the people who will live in the housing. And in this you're looking at the people who build it and the process by which they build it. So as you put it, neighbors may oppose not just the product of housing, but its producer and the process the producer uses. So have we just not given enough thought to the role of producers and processes in the past? Like what motivated this question specifically?

Paavo Monkkonen 9:18

Yeah, no, I mean, I think that is the right distinction, like things that will directly affect your life and things that actually won't affect your life, but you find, reprehensible and make you mad. I got to say we got to give credit to the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, to a great extent because this work was in part motivated by the Measure S campaign in LA and the way that they used evil developers as a trope, kind of in their opposition to large buildings being built in the city. And so that really...

Michael Lens 9:53

To interject, the Measure S campaign was, I believe, something that LA voters vote on in November 2016, I think.

Shane Phillips 10:03

I think It was March 2017. It was after Measure JJJ, which was in 2016.

Paavo Monkkonen 10:09

Okay. Yeah, it got pushed back to them.

Shane Phillips 10:11

Yes.

Michael Lens 10:11

Right. And so that would have really put a stop to any development that required a modification of variance of existing zoning, right?

Shane Phillips 10:24

Yeah, which at the time was like the majority of housing production. So it would have had a really big impact for sure.

Paavo Monkkonen 10:31

Right. Yeah. I mean, and so, you know, opposition to housing was something that kind of I had been thinking about and studying for a while. But this campaign and the prevalence of this evil developer trope was why we included it. And it wasn't the focus of the survey initially. I mean, it's the title of the paper in the end, but it wasn't the focus of the survey. Because we weren't expecting it to be such a big, as provocative of a frame as it turned out to be.

Shane Phillips 10:57

You open the paper saying that most research on opposition to new housing focuses on low income housing, affordable housing, and that opposition to market rate housing is under studied. What changed? Like why is this a thing now? Like, why weren't people studying market rate housing and people's responses to it? 10, 20, 30 years ago?

Paavo Monkkonen 11:19

Yeah. I mean, it is a good question. I don't know why. Precisely. I mean, economists have been focused on measuring the impacts of regulations for a while on housing markets. I was thinking you know, planners, planning scholarship, maybe has been less, you know, maybe resistant to questioning community concerns. But I don't really have a great answer. I mean, I think it is also because we used to build a lot more market rate housing in the US. And so it wasn't necessarily as big of an issue, kind of in terms of housing affordability as it has become over the last couple decades.

Shane Phillips 11:57

Right. And it's just gotten so expensive too, right?

Paavo Monkkonen 12:00

Yeah, exactly.

Shane Phillips 12:01

The gap between I think, I don't know the numbers off the top of my head. But I imagine the gap between a new market rate unit today, and a low income unit is a lot larger than it was, you know, in 2000, or 1990.

Paavo Monkkonen 12:13

Um-hmm.

Michael Lens 12:14

Yeah, you know, if I were to offer some of my thoughts, I mean, the renter affordability crisis, or sorry, the, the cost of housing for renters as a proportion of their income, you know, that is steadily risen for many decades. And alongside that, you know, some would say, as a result of, or some would say one cause is that, over that same time period, a lot of cities have become kind of more exclusionary, you know, and so, of course, there's a lot to pull apart there in terms of causality. But, you know, those two trends certainly have, I think, hit a fever pitch in our examination of the more acute housing crises that occur in really high cost places.

Paavo Monkkonen 13:08

Yeah, no and I think, you know, there are a number of topics that are just not heavily studied, even though they're important. I mean, like, so Shoup is famous for putting parking on the map as a topic of study that people just hadn't realized its importance. I mean, or like in the housing world, I think Matt Desmond, obviously, put evictions and landlord ism on the map in a way that... and now there's going to be a lot of studies of that, and I think... In his book, I love that footnote that's like, you know, the volume of papers on the details of the structure of voucher systems, compared to the study of other aspects of rental housing. You know, it's like this hugely outweighs it. And, you know, there's just things that we haven't focused on for whatever reason that we probably should.

Shane Phillips 13:52

Yeah. Let's talk about some of the details of this paper. And I think I can just start off by actually reading some of the questions and messages that were given to the survey takers, just as a starting point. The control group for this, are they people who actually lived in predominantly single family neighborhoods? Or were they just to treat themselves, pretend as though they were?

Paavo Monkkonen 14:16

Oh, yeah, no so what we did is we asked people what was the kind of predominant building form in their neighborhood and then, depending on what they answered, we had kind of three groups. If they were living in a mostly single family neighborhood, the hypothetical project was like, I forgot, six plex or something, you know, like a three storey apartment building. If they were living in a kind of mid density neighborhood, it was a 10 storey apartment building. And if they were living in a high density neighborhood, it was a skyscraper. So it would be bigger than what's there now, right?

Shane Phillips 14:47

Okay. Yeah, yeah. The question to people living in a predominantly single family neighborhood was, suppose the developer proposes to build a three storey apartment building on your block, the proposed building, which will contain 21 bedroom and studio units is designed by Camarillo architects who have developed multi-family residential projects across Southern California for decades. Early renderings show a building with tasteful contemporary architecture and ecologically sensitive landscaping. Some advantages of this development are clear. Los Angeles badly needs more housing and city planners, hope that new construction will help make rents more affordable. And so that's for people living in predominantly single family neighborhood.

Michael Lens 15:26

I gotta say maybe the name of the made up architect ecologically sensitive landscaping is probably my favorite part of this paper.

Shane Phillips 15:34

I think, yeah. I think for each of these, you gave kind of just made up architect names, but they're just kind of like, southern california...

Paavo Monkkonen 15:41

I mean, come on...

Shane Phillips 15:41

... spanish names.

Paavo Monkkonen 15:43

... I could work for urban...

Shane Phillips 15:44

And so for people living in predominantly multi-family neighborhoods, the building size is increased to 10 storeys and 90 units, but the message is otherwise the same. And I guess for like even higher density neighborhoods, you give like high rise as the proposal. But as you say, it's always a little bit bigger than what's in the neighborhood currently. And, as you said, some survey takers, were just given that message and you know, you asked about their feelings on it. And then for others, you gave them an opposition message, one of several. And just for example, the one on cars and traffic says, "however, some of your neighbors oppose this project. They worry that it will lead to increased traffic in the neighborhood and make street parking harder to find. Traffic and parking are always sources of concern to Angelenos. And there is reason to think that new housing does mean more cars". And there are other opposing messages on neighborhood character or strain on local services. And the last one about developers. And that developer one says, "however, some of your neighbors oppose this project, they point out that the project's developers obtained a special permit from the city, which lets them build at a higher density than zoning would normally allow. The developer stands to make large profits as a result, your neighbors argue that the city planning department should not be in the business of making developers rich", so you really land it on there. So as you kind of hinted at, the biggest change was actually... came when people were told about the developer gaining large profits from the development, it was a 20-point swing, so the control group that didn't receive an opposing message, they supported this project in their neighborhood. 53% supported it, 28% opposed it after hearing about the developer making profits and getting this variance, support fell by 20 points to 33%. And opposition rose 20 points to 48. So I guess, like at a very high level, like what do we do with that finding? I mean, even if developers don't hit their target, investment returns like instead of making 8% or 10%, they make 2%. And it's just a big failure, the average person is still going to interpret that as like a big profit, because 2% returns on like a $10 or $15 million development is a lot of money. So like, where do we go from here I guess?

Paavo Monkkonen 18:08

Yeah, no, it's a striking result. And I think, you know, you might have noticed in reading that, that we mistakenly had a double barreled argument against the project in there, right? So there's like the special permit, and then the profits. So that's definitely something we want to redo this study. I mean, I hope this podcast attracts some funding for a follow-up survey, because, you know, we didn't anticipate it having as big of... like being the focus of the paper in the way that it became. And because of the Measure S campaign and the way it was structured, and I mean, because of LA politics and the way it was structured, in terms of so many projects requiring variances or zoning, you know, amendments, you know, this became a big part of what we're interested in studying. But yeah, so what do we do with it? Well, I mean, we got to worry about those things separately, right? So the perception and actual corruption in the housing development process is a big problem. But also kind of there's this,kind of repugnant market element to the housing development system, we think, right? So you know, this idea where profiting off human needs, profiting off organ transplants kind of are things that people perceive as immoral. And I think there's an element of that with housing. And I think it gets worse, or gets more acute when housing is so unaffordable, and there's so much homelessness in the city, right, then housing as a basic, like the basic need element of housing becomes much more salient in people's minds. So I think yeah, I mean, I think, you know, thinking about reforming the permitting entitlement process to make it less special for certain developers is extremely important. But the other part , the repugnant markets part I don't know what kind of any policy recommendations would come from that.

Shane Phillips 19:58

Right, like there's more we can do on the special treatment side of things, probably than the developer profit.

Paavo Monkkonen 20:05

Right.

Shane Phillips 20:06

Do you think, I mean if you had to guess, and you know, pending a lovely person coming in and funding this next study, do you have a guess at which of these actually changes people's views more?

Paavo Monkkonen 20:19

No, I couldn't. I mean,

Shane Phillips 20:21

Couldn't even guess.

Paavo Monkkonen 20:22

We need to do more research on it.

Shane Phillips 20:24

Fair, fair. So the developer... I've been...

Paavo Monkkonen 20:28

Well just on that, I'll say, I mean, they are connected too, right? So I think, you know, one of the big arguments that we've been making, to the city council recently, I know, there's a motion, a couple motions about reforming the permitting process, just because of the corruption scandals in the city of LA, you know, to some extent, the process creates the excess profits, right? So the fact that if you do get a variance, or you can get an amendment to the zoning, then you're gonna make way more money than somebody that can't get that, right? So it creates the impetus for more corruption. And it benefits those developers that are really good at corruption, right? Are really good at getting that special permit, right? So to some extent, I mean, that's kind of some of the big picture keynotes, maybe making more out of these findings. And we should, according to the rules of academia, but I think to some extent, you know, we have created a city planning process that makes people dislike it more than they would otherwise. I mean, it reminds me almost of like the republican strategy of like, making government dysfunctional, and then saying, look, government's dysfunctional. So right, we've created this process where every multi-family building needs approval by elected officials. And then they get a lot of flak about it when they approve buildings, and there's all this kind of negotiation behind closed doors to developers, etc. And then, of course, people are going to be mad about that, right?

Shane Phillips 21:56

Yeah.

Michael Lens 21:57

Right. And but, you know, these findings, you know, you're being a little bit modest. I mean, these findings come well before, this experiment comes well before we see, you know, council member who is... have, you know, these very explicit charges of corruption, brought to them after extensive FBI investigations. You know, council, former council member Englander resigning, and it turns out was receiving suitcases full of cash and has pled guilty to various things associated with that...

Shane Phillips 22:37

Excuse me, I think it was just a paper bag.

Michael Lens 22:39

Oh, sorry.

Shane Phillips 22:42

I could be wrong, I could be wrong.

Michael Lens 22:43

Right, the developers weren't that fancy, they didn't have that much money. They didn't have anything really to carry it in, it wasn't sophisticated. So you know, there could be reason to believe that. You know, that developers and council members in this city at least half are kind of bringing their or they're attaching themselves to each other's bad names, perhaps. But, you know, the, I guess one thing that comes to mind, for me thinking about this at this stage is like, what do people think developers are? You know, is there a difference? Is there a difference between what developers do and function as and what people perceive? And, you know, I know, Paavo that like, this is not the central focus of this study, for sure. But like, Is there a disconnect between what developers are and do? And then of course, developers are diverse group. Yeah, there's... not all developers are the same size or massively profitable.

Paavo Monkkonen 23:52

There's those mom and pops?

Michael Lens 23:54

Oh, well, I wasn't gonna go there. We only use that with landlords.

Paavo Monkkonen 23:57

But yeah, no, I think that's the point. That's a good point. And, you know, it's something that I've been talking about, at least with council members in the city of Culver City about why aren't cities more proactive about what they want in terms of housing production? Right. So our system currently is the developer has to have a parcel, have an idea, come to the city, and present it to the city and the city can cut it back and adjust it and nitpick and may or may not approve it. Instead, I feel like the way we would have a housing system where housing was getting produced at a pace that people need it would be the city should say, here's a bunch of land on which we want housing to be built. It should have these parameters more or less please go build it for us. And kind of like we don't hate car producers, maybe SUV producers, but most cars... like most producers of products people don't hate intrinsically and I think it's just this kind of, you know, there's this element of you don't want your neighborhood to change. Can't get around that but I think part of the kind of the developer-city nexus issue is the way the negotiation is set up.

Michael Lens 25:07

Hmm, that makes a lot of sense.

Shane Phillips 25:09

Right. And, you know, it maybe worth emphasizing that earlier Paavo said, you know, we use the word corruption. And there's real corruption happening here in the city of Los Angeles, like very clearly. But most of these approvals, like this is how you get housing approved. And it gives that appearance of corruption, whether it exists or not.

Paavo Monkkonen 25:30

Right.

Shane Phillips 25:31

But you know, getting that zone change, that variance or what have you, especially prior to the Transit Oriented Communities Program here that was approved several years ago, as I said, that was the majority of housing being produced and like, you had to go through that process, and it looked terrible. But if you couldn't get that zone change, you basically couldn't build anything, meaning, you might have a site that's like, still zoned for manufacturing, even though it's been vacant for decades or literally just for parking. And so this is like a shift away from that, is what we're talking about.

Paavo Monkkonen 26:02

Yeah, I mean, even in cities with less Byzantine zoning codes than the city of LA, there is always this element of kind of like a pre... before the developer even submits any paperwork to the city, they kind of have some meetings and float some ideas, right? And like, ultimately, they need the city council to vote on something. And they know that vote is going to be contentious. So they're kind of warming them up before even a formal process starts. And so yeah, I mean, it is this... there's an inevitable perception of backroom dealage, at least if not corruption.

Shane Phillips 26:36

So opposition to developers, you know, that was kind of a surprise finding here, it's the main takeaway of the paper. But I was actually surprised that of the other opposing messages, neighborhood character was the next most effective. Again, the other two were traffic and parking, and then strain on services. And we hear people talk about neighborhood character all the time, and how, you know, allowing duplexes in your neighborhood will destroy a neighborhood character or, you know, turn it into Dubai, or whatever. No reference there. So there's this connection, I think, is not really made explicitly, very often, there is this implied connection that like, by protecting the built environment, we are protecting the people who live there as well. And like maintaining whatever that mix of people is. And that means different things in like a rich white community than a poor community of color, of course. But like, what do people mean, do you think when they're talking about neighborhood character, and I think we see this in both rich and poor, where it's like, Los Angeles, over the past several years, has created all these new zones to prevent like mansions, like tearing down a single family home and building a bigger one. So it's not just like keeping poor people out of your neighborhood. There's also like, pretty rich neighborhoods, where it seems like they don't want even richer people in their neighborhood either. It's like, just keep everything the same.

Michael Lens 28:01

Every one is a little bit like me, but slightly richer, maybe?

Paavo Monkkonen 28:04

No. Yeah. I mean, I think I thought it would be the most provocative frame that we used, just because it is so vague. I mean, I realized in rereading the way we set it up, we were a little bit specific on the buildings, right? So we said it's going to be out of context, this new building, like the concern was that it was going to ruin the neighborhood character, because it was going to be out of context. If I could do it again, I would just say, neighbors are concerned that it'll ruin neighborhood character period. I wanted to leave it vague, just because it means so many things, you know, it means different things to different people. And it even encompass... I mean, the reason I think it's bigger than traffic or the strain on services is because it includes traffic and strain on service, right?

Shane Phillips 28:48

Hmm.

Paavo Monkkonen 28:48

So part of the neighborhood character is kind of the existing traffic and parking condition. So yeah, I mean, I think, you know, people think about it in different ways. You know, I think some neighbors are more concerned about the buildings being different. And like, don't mind that prices are going up, especially people that own housing, are happy that prices are going up, as long as the conditions don't change, whereas other people are more concerned about kind of who's living in their neighborhood.

Michael Lens 29:15

If he made a follow-up on that last piece, Paavo I mean, you know, the more academic theories, and you know, this is supported by plenty of empirical study suggests that, you know, who really influences these decisions over development in most American cities in particular, and more specifically, in more suburban areas are homeowners right? That have so much of their household wealth tied up in the property that they own, and so they're fiercely protective of property values, or even... they're fiercely kind of oppositional to anything that might impact their property values, right?

Paavo Monkkonen 30:05

Yeah.

Michael Lens 30:06

And so they're, you know, they don't want lots of competition over amenities if it's a good school or if it's a local park. And there's also, I guess there's this neighborhood character sense that having multi-family near you is just kind of a bad, ugly thing, right? You know, how much do you feel like you saw that come out in your study?

Paavo Monkkonen 30:30

Yeah, I mean, it would be nice to know, kind of how the single family neighborhoods differed from the more kind of already slightly dense neighborhoods in the sense, one of the drawbacks of the way we did the study is that the sample of respondents wasn't randomly drawn from the population of LA County, right? So we used a company that has a panel of survey contestants... respondents, that's a Spanish-ism. And so, you know, it was a balanced sample, for the most part, which means kind of, in terms of race, ethnicity, gender income, kind of it more or less mapped on to the population of LA County, but it wasn't randomly drawn. So we can make inferences about kind of how single family neighborhoods answer these, kinds of people in single family...

Michael Lens 31:18

Right.

...answer these questions different. But yeah, I mean, I do think it is different. And it would be great to have, like an actual random sample to do this work with because you can imagine that single family homeowners are extremely different than renters in some of these responses. I mean, I think also with the neighborhood character thing, I mean, it would be... I would love to partner with a psychologist or something to study kind of how people's, you know, because there's this like whole American myth of white supremacist, single family picket fence theory. And like kind of how many how much those myths drive some of this neighborhood character mentality versus like raw risk, you know, loss aversion risk, like maybe my property value will go down. I mean, that is something we didn't have a frame on, like, neighbors are concerned that prices will go down in this neighborhood, that would be another frame to include in a follow-up study, because kind of just disentangling, like, changes in what the neighborhood looks like, who lives there, and then just some kind of raw financial thing would be interesting.

Shane Phillips 32:25

And that's something you'd really want to have a breakdown between renters and homeowners.

Paavo Monkkonen 32:30

Right.

Shane Phillips 32:30

Presumably, you're gonna have a big difference where like homeowners want prices to go up. Renters want them to go down.

Paavo Monkkonen 32:35

Yep.

Michael Lens 32:36

Right. And that's exactly right. With this phrasing of neighborhood character, it's so ubiquitous in these discussions at the neighborhood level on development, and yet, it has to mean so many different things to so many different people. And you do worry that there's a lot of disingenuous use of that phrase as well, right? You know, as we've talked, I think Shane brought up several minutes ago is like, there's the buildings changing, there's the people changing. And so like, that could be covered in neighborhood character and be a softer way of expressing opposition to certain people, right?

Paavo Monkkonen 33:25

Um humm.

Michael Lens 33:25

And so like, how do you, you know... Pulling that out I agree, you know, almost requires a behavioral economist or a psychologist or something like that.

Paavo Monkkonen 33:38

Yeah. No, and I think it's something people don't think about probably that much. But this point about preserving the buildings almost means that people will be different. I mean, especially, you know, in affluent, single family neighborhoods where, like, there's a lot of housing development, meaning bungalows are being torn down, and mansions are going in instead, right? So like, keeping the restrictions on FAR and units per acre, or whatever it means that the neighborhood that looks similar, but the people are much richer, that are able to move in, right? And so I think people when they're presented with it that way, it might... I have seen it kind of make people think twice about their opposition to changes in zoning.

Michael Lens 34:24

Right. And for our listeners out there, who do not routinely dork out on urban planning discussions or concepts. FAR stands for floor to area ratio. It is really good to just kind of give you a sense of how tall you can build something on a plot of land.

Paavo Monkkonen 34:43

And there's a really fascinating discussion about FAR happening right now in the city of Culver City. Should it be 0.6 , the city just reduced it to 0.45 from 0.6 for their R1 neighborhoods. And I think California YIMBY, YIMBY Law's threatening to sue them about it. It's pretty interesting.

Shane Phillips 35:03

Mike, you say this, like the listeners aren't listening to a podcast about housing research. So good to clarify regardless, but I suspect most are already in the know.

Michael Lens 35:14

I hope we have a general audience...

Shane Phillips 35:18

We'll get there, we'll get there.

Michael Lens 35:19

...it's generally interesting.

Shane Phillips 35:21

And so there's more to this paper, we've only covered some of it actually, so far. And the next part is looking at not just opposition to or support for housing in people's own neighborhoods, but somewhere else. So like the real "NIMBY", not in my backyard, like I support it somewhere else, but not here kind of view. Can you tell us a little bit about how that changed things when you move to the project from in their neighborhood to maybe a mile or two away?

Paavo Monkkonen 35:52

Right. Yeah, no. So I think that was like, I was maybe not surprised by the numbers. But other people told me it was an important finding, just because there is some kind of questioning of the idea of nimbyism being, you know, like, I want housing to be built somewhere else, but not near me, which I kind of just assumed to be the case for many people. But yeah, so you know, of the people... the finding was of the people that oppose the development, you know, the hypothetical development on their block, then we later asked them about an identical development, you know, several blocks away or farther away. And of those people, so they opposed to the first one near them, then in the next one, 23% of them actually liked it, they supported it somewhere else. And another 21% of them had no opinion on it happening somewhere else. So nearly half the people that opposed the housing near them, were okay with it somewhere else, which is pretty interesting findings. And so you're getting at like, our people, just they oppose it in their neighborhoods, but they actually are okay with it elsewhere, so that's the NIMBY position, or is it the "banana", the build absolutely nothing anywhere near any one position. So half of the people are consistently banana. They don't want it near them. They don't want it anywhere.

Shane Phillips 37:12

I mean, something to be said for consistency.

Paavo Monkkonen 37:15

Yeah, no, I like them better almost.

Shane Phillips 37:17

And the last thing you looked at was how community benefits could mitigate some of the opposition. And you gave the survey takers a few different messages about how those benefits were secured, you didn't really say like what they were, it was more about how they came about. And so one said that the developers proposed them voluntarily. Another said they were forced by the community, like through negotiation. And then the third said that they were required as a matter of course, by the city, and you added at great expense to the developer. And so you found that almost two thirds of respondents became more supportive after hearing that the developer offered the benefits voluntarily. And that fell to 57%, increasing their support when it was negotiated. And then it was 50% more supportive when the city required them. And actually, for all of these cases, there was like 3% to 5% of people who actually became less supportive when they were told about community benefits, and presumably, those were, like developers or something. But I think that was surprising. And, you know, we've been doing a lot of work on the approval process in our own research and looking at like, by-right approvals, versus discretionary approvals. By-right being like, if you meet the requirements of zoning and building code, and everything, you get approved, and there's no real negotiation there. Versus discretionary, where there's a lot more veto points. And, you know, this was, honestly a little disappointing for me to see this result, because the message where it was just like required as a matter of course, which would be basically a by-right approval with community benefits as a part of that. That had the least support, like it improved support the least. So like, did you kind of have the same takeaway from that? or?

Paavo Monkkonen 39:09

Yeah, I mean, it's interesting, I think the... having more experience since I've done this with talking about specific projects with community members, I think the fact that like voluntary contributions on behalf of the developer, made people more likely to increase support isn't surprising. I think I hear a lot that people like nice developers, right? Or at least perceived nice developers, like that really does influence their opinion, right? I think because maybe it's connected to this, like they're coming into where I live to do a project. So I want to make sure they're nice. And then the losing money is surprising, like given that the fact that they made money, made people so much more likely to oppose a project. The fact that they're made to lose money, not kind of increasing support very much was interesting. So people don't want them to make money, but they also don't want to hurt them.

Shane Phillips 40:05

Can't make their minds up.

Paavo Monkkonen 40:06

Yeah. I mean, I'm not sure how it affects kind of, I hadn't thought about it in the context of discretion or non discretion. But yeah, I mean, it maybe you know, that just this in the reframing of what the development process is that we sort of talked about before kind of what the city's role is, and what the developer's role is, in this process. You know, you could imagine a discretionary process that also includes the developer having to do something voluntarily, or, apparently voluntarily to, like, make the neighbors like them.

Shane Phillips 40:37

They're mandated to come up with like something, but they get to choose.

Paavo Monkkonen 40:41

They are forced to do, yeah, something spontaneous for the neighborhood.

Shane Phillips 40:43

Yeah. I mean, it sounds silly. But I wouldn't be surprised if it kind of worked. I'm going to ask. I'll ask one more, and then we're going to be kind of coming to the end. But, so you surveyed LA County residents for this. And it's possible that a message that's effective in LA County might not be as effective other places or might be more effective. Do you... again, like asking you to guess a little bit and I apologize, as an academic for doing that. But like, do you have a sense for how things might look elsewhere? And I'm kind of thinking about the Hankinson paper from, I think 2018, where he found that in higher cost cities, renters tend to develop more NIMBY attitudes, versus like more middle tier and lower cost places where they're a lot more pro housing, even in their own neighborhood.

Paavo Monkkonen 41:35

Um Humm. Yeah, no, I mean, it is a pet peeve of mine, when people take studies that were done in one city, and then extrapolate the findings to other cities, because cities are different, especially in terms of their housing markets. So yeah, I think that definitely you know, the context influences these results, for sure. And especially kind of that Measure S campaign that we mentioned, having maybe primed some of the respondents if they had seen those big billboards or heard about the fight, or heard about kind of allegations of developers in city hall, you know, that might have primed them to answer in the way they did. So, you know, it might be less of a big deal in other places, there's no way to know without doing surveys there as well, so...

Shane Phillips 42:21

I guess I should clarify. When exactly was the survey done? Was it like during the campaign or afterwards?

Paavo Monkkonen 42:27

It was afterwards, I think a couple months afterwards.

Shane Phillips 42:30

it was shortly afterwards

Paavo Monkkonen 42:31

Yeah, yeah. But yeah, I mean, we'd love to do similar surveys in other places, just to get at that variation.

Michael Lens 42:39

Yeah, you know, and if I can, again, maybe I can push back on some of your modesty, you know, I think that we do want to be cautious when generalizing to other markets, other cities, other conditions. You know, sometimes that's the best we have, or sometimes you can also make pretty good arguments that, particularly within the United States, there's a particular culture with respect to zoning and land use and single family zoning in particular. There are things that we share as in terms of planning concepts, and you know, that are not obviously identical from Cleveland to Seattle to New York, but we do share a lot of similarities.

Paavo Monkkonen 43:31

Yeah, no, I mean, and the evil developer trope that we talk about, and give links to the website about is definitely you know, that's the whole country since the 80s, right? I mean, I think that..

Michael Lens 43:43

Right.

Paavo Monkkonen 43:43

Now, maybe it would be even more dramatic now, considering that the President is an evil developer. And so, yeah...

Michael Lens 43:51

Maybe an interesting model that I just came up and I'm workshopping with our audience is, greed is good, but not in my backyard.

Paavo Monkkonen 44:02

Yeah, no, I mean, and I think you can... you know New York definitely has a lot of famous evil developers that I'm sure people are primed to dislike them getting rich.

Shane Phillips 44:12

Is there anything we missed in your paper?

Paavo Monkkonen 44:14

Well, something we do touch on a little bit is kind of among the planning literature and how planners have written about developers. I think, you know, so there's this issue of kind of how the public perceives City Hall and development and developers and the relationship between them. But among city planners, I think there is like a detectable antagonism to developers in the academic literature and perhaps among practitioners, although I don't have evidence of that, you know, and it's interesting, and especially in the RHNA fights in Southern California, kind of this mantra of like "cities don't build housing, you know, developers build housing and kind of the city's responsibility is to do the zoning and then argue with developers when they propose projects". I think that's something that you know, we don't really dwell on what to do about it or kind of how to study it further. But I think thinking about how we need to reframe that relationship, maybe and think about how city planners and developers, you know, have to work together. So what can we do to make it a relationship that is less repugnant to the populace, and kind of a more effective and productive relationship that builds housing for people?

Shane Phillips 45:27

And we can put in another explanatory comma there with the RHNA which is the...

Paavo Monkkonen 45:33

Yes, oh man, I don't know which wave or time.

Shane Phillips 45:34

No, yeah, the Regional Housing Needs Assessment. I don't even know how to define that thing, man. It's confusing. It's basically the state telling us, every city, how much housing they need to plan for over the next eight years.

Paavo Monkkonen 45:48

Right.

Shane Phillips 45:48

And it has a nice little acronym called RHNA.

Paavo Monkkonen 45:51

But I mean, I think, you know, in that, you know, the state law says "cities are responsible to provide some zoning that allows housing to be built", and that's it. And then cities kind of can comply with the law, but actually not allow any housing to be built. And it's like a fundamental problem with the way California has dealt with housing, you know, increasingly over the last few decades. But it does go at this kind of, you know, we can do whatever we want to, to extract money from developers and, you know, block them and make the process more difficult, without really recognizing that the negative impacts of housing shortage are real and hurt renters, at the same time that they make most elected officials rich, because they're all homeowners.

Shane Phillips 46:35

And since we want to keep these podcast episodes coming, is there a paper out there that you'd recommend for us to look into in the future or something? It can be related to what you did here or unrelated, it doesn't matter.

Paavo Monkkonen 46:48

Good question. I mean, related. The one reference that we include, people might be curious about this study and thinking about framing of housing development. Tiffany Manuel at Enterprise did a cool kind of resource pack about framing. I think it's specific to affordable housing production, but it applies to market-rate housing production as well in terms of kind of framing from the developer's perspective, projects to people. I like that resource a lot. And then the two (second) paper that Andrew Whitmore and Todd Bendur, did some similar work on framing, around density, more about positive frames and how they impact attitudes towards density. So those are nice papers. In terms of new work, there's a lot of interesting stuff out there about the impacts of housing development on rents nearby. Professor Lens has interesting work on evictions, I'd like to hear a podcast about that. That's what comes to mind.

Michael Lens 47:45

I'm sure we will go down that rabbit hole soon.

Shane Phillips 47:49

And where can our listeners go to read more about your work?

Paavo Monkkonen 47:52

I don't have a... I mean that Luskin website? I don't know if it has updated... Google Scholar Um...

Michael Lens 47:59

luskin.ucla.edu. Also check us out at the UCLA Lewis Center.

Paavo Monkkonen 48:04

Oh, yeah, that has a lot of good policy briefs. I highly recommend it.

Shane Phillips 48:09

Well, just...

Michael Lens 48:10

You can follow us on Twitter @elpaavo. That's @elpaavo

Shane Phillips 48:18

Oh, the turkey!

Michael Lens 48:23

Yes, our Spanish speaking audience will recognize that it sounds a lot like....

Shane Phillips 48:28

And we'll, you know, we'll just do something like, have some show notes and put your CV in there just for... people who love to read that. That's it for today's episode of the UCLA Housing Voice podcast. Thank you for joining us. We have links for our guests in the show notes and you can keep up with us on Facebook and Twitter at UCLA Lewis Center. You can also follow Lens and I @MC_Lens and @ShaneDPhillips. And if you like what you hear, please help other podcast listeners discover us by rating and reviewing the show on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen. Thank you again for listening and we'll see you soon

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

About the Guest Speaker(s)

Paavo Monkkonen

Paavo Monkkonen is associate professor of urban planning and public policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. He is also a Lewis Center affiliated scholar.Suggested Episodes

Subscribe to our Substack